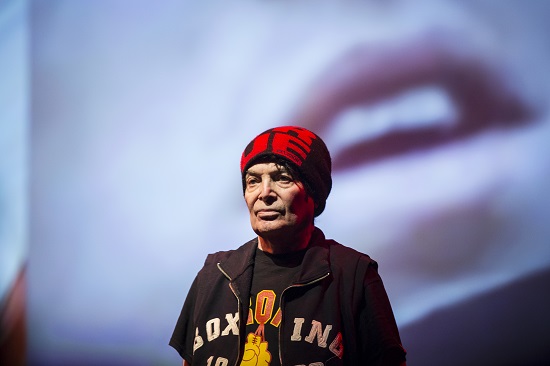

In his pre-show address, frothy punk minotaur Henry Rollins is telling a story, which of course he’s pretty good at. A formidable, not to mention unnervingly intense orator, the man’s a bay-shelling battleship that looks like a man but talks about music with the glee of a 12-year-old who woke up and realised he could fly. Assuredly, never was there a purer punk soul than old Henry.

The story he is telling is the account Thurston Moore’s first encounter with Suicide, in late 70s New York. Or, the “most frightening night of [Moore’s] life” as Henry explains. On this particular evening, Martin Rev and Alan Vega had taken the decision to chain themselves to their instruments, which, considering the usual sequence of events when Suicide performed was nothing if not gravely ill-advised. As was frequently the outcome of any Suicide gig, the crowd reacted with fear and revulsion, hurling objects at the duo, everything from glasses and bottles to lit cigarettes and ash trays. As Rollins reminds us, this was Greenwich Village in the 70s, bastion of the cynical hippy. Beyond the men’s alien clothing style and their futuristic sound so violently introducing the spent hippy generation to a future without them, an act sporting that name was enough alone to earn them a complete tuning.

Unable to move but refusing to desist, the men were forced to stand there and take everything. And so they did. It was a classic Suicide endeavour: an act of self-abasement, submission and blood-letting, of the kind so popular in 70s New York amongst the performance art-set, the fattened Soho art establishment despised with gusto, and a grand idea you imagine was Rev’s, whose early sculpture art before Suicide centred around crucificial symbolism.

Soon enough both men were bleeding – Vega from the point of those sheer, carved features. His blood oozed downwards, you imagine, to mingle with the sick vowels of that profane poetry, disfigured further still by a ghoulishly delayed mic effect. But it was the sight of Martin Rev that did it. Garbed in signature visor shades, as the abuse rained down, the synth player crashed his hands, arms and elbows through all the broken glass that had accumulated on his keyboard. And all the while the duo’s cruel, devastating music continued its sad trajectory, like a boredom, like a terrible eternity. Only then did the crowd relent. “They were like, okay, you win… you’re scarier than us” as Rollins tells it.

This is a story about conflict. The kind of conflict, as Rollins mentions, that defined his own kind of performance art, as frontman for Reaganite America’s first hardcore act, a terrifying battle which from day one, he reveals tonight, Suicide’s endless courage in the name of art gave him the inspiration and the strength to fight, ever since he and Ian McKaye bought their first Suicide record as teenage boys in DC.

The question is, can such a dynamic exist tonight? We’re sat in the tasteful Scandanavian-style surroundings of The Barbican’s main hall, and it’s a long way from the arteries of molasses of the Lower East Side. We’re sat down, and in neat rows, each clutching our paper programs and at the ready with small talk for nearby associates, discerning types like Islington creative, glamorous European gamine turned gallery owner, 20-something cool hunter, middle-aged man in Killing Joke t-shirt, old Camden part-time punk, purse-lipped music journalist quasi-pseud(me) and one Bobby Gillespie, whose appetite for being seen at edgy London events is equal only to his passion for making wrist-slitting-ly reactionary music. The punk mass is very much being preached to the choir.

This is ‘an audience with Suicide’. We’re here to pay homage, to a duo who, considering Vega’s ailing physical and possibly mental health, could potentially be the last time they share a stage, and we will not be denied those bragging rights.The set-up is reverential: we look upwards to the heavens of tonight’s hosts, the gulf between performer and stalls distancing. Whereas before there was a hell, the audience peering over the edge to vomit and bark into the psychic hole Suicide excavated every night in recession-era Manhattan, tonight, however, we are passive spectators and they the spectacle. This is theatre, not ‘happening’. For best results, next time please park the Suicide road show a quarter mile up the road from the Barbican, where the city rises out of East London. Industrialised terror can penetrate glass and seep out into rotten hearts. The sky turns black with pin-striped precipitation as the suits rain down from helicopter rooftops. That would be conflict.

All told, it’s exactly the kind of artsy love-in the duo would have run their acid tongue through in 70s New York. But with the chances of tonight even remotely resembling a Suicide ‘happening’ at zero, the only thing left to do is let the ravaged geniuses go out peacefully, and choose the method of their own destruction, because after all they’ve they’ve earned it. As Rollins remarks, “My safety nets have safety nets. Suicide, however, for four decades now, have been operating without one.” As the Disneyland above us churns in the summer evening heat with legions of people who will never know the names of these men, in the darkness of the Barbican basement the unknown soldiers on stage enjoy a kind of homecoming party: given their due props by the art establishment (for good or ill) who once disregarded them as shock-art goons – a too-small contingent who know that Suicide’s “ultimate music” (Rollins’ term) and their bravery and unbending resolve in executing its dissemination changed both art in music and whole lives. If you have to see one heritage act in this nostalgic era of reforming bands and the endless recycling of ideas, you might as well make it Suicide, the most futuristic act of their era and many more beyond.

And after all is said and done, they still manage to subvert the scenario in tiny but significant ways. By the end, you leave feeling like, after all these years, the joke is still on us. For starters, despite their back catalogue containing ample examples of hymnal music— some of the most beautiful synth music ever written – is far from the advertised ‘mass’. Apart from one very poignant moment of respite near the end, this is a roaring and ruinous noise showcase, which fills the operatic limits of the main hall with fear and human evil and modern disease right up to its 70-foot high rafters.

The men begin by performing their own solo sets, giving them a chance to showcase the contrasting styles they’ve developed through the years, both of which are terrifically disquieting but in very different ways. First is the turn of Marty Rev. His segment is listed on the program as ‘Stigmata’.

The original electro-goth, he saunters onto stage like a street-tuff New York longshoreman with an unapologetic fetish for cum-washable biker gear, his tiny emaciated bottom mushrooming over his black PVC pants (with matching top); signature visors present and correct. To match his garb, Rev’s music is comparatively sexual next to Vega’s inhuman mechanical onslaught. Doo Wop meets head on with the screaming tinfoil waves of a violated Korg synthesiser in Rev’s psychosexual ode to ghost starlet. A deeply unsettling prospect, he inhabits the character of a suicidal loner for whom reality and fiction are merging in the new hyper-reality of 50s America. Obsession and impotent desire become one for a perversely romantic torch song, as was often the way of things with Suicide’s music. “I love your films” he moans, “Why am I so sad?" In a disturbing twist, Rev directs his deathly pleading towards the three female backing singers behind him, who stand serenely and submissively like drugged dolls and accept it smiling. Back when Lynch was still just a young expectant father losing it in Philadelphia, Suicide were doing with music what the director would go on to do with film – splicing dreamy kitsch with pure terror. Because for every American dream there is its equal and opposite nightmare. Demonstrating Rev’s genius for manipulating the semiotics of Atomic-age America for dire effect, it was the definition of sound art – the direct sonic descendent of a détournement collage.

But queasier still are ‘Domine’ and ‘Sanctus’. To this writer, these tracks were an exploration of what lay beyond the homeland, in the cradle of 20th century evil that was Europe. If you’ve ever seen Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon you’ll know exactly the kind of queasiness that’s being presented. The cinematic ‘Domine’, with its swooping strings and sense of political intrigue, evokes Europe after the war where, in the apocalyptic ruins of civilisation and a godless vacuum of order, men fought for survival with terrible acts. You’re reminded of Paul Buckmaster’s playfully fatalistic 12 Monkeys OST or even Anton Karas’ ‘Harry Lime’s Theme’ from The Third Man. The mighty ‘Sanctus’ meanwhile, with its titanic brass and spectral vocals, evokes an unstoppable army of Nazi dead, advancing west; their imminent arrival announced by the weeping of the winds. Though both men found their audience in mainland Europe, for Suicide anyone was fair game.

But the war machine is really Alan Vega’s deal. His set, entitled ‘Throne & Strobe’ and characterised by the oddest most resonate kind of caramelised industrial and rampaging techno, presents a contemporary America sickened on its own high cholesterol imperialism. On the balcony above us a woman is screaming a torrent of ecstatic glossolalia (part of the show?), as a grinning Vega, his voice reduced to an animalistic gargle by old age, presides over a maniacal terror-ride. Performing tonight with his wife and son, pre-recorded vocals give rise to not one but three Alan Vegas. The trio of men take turns arguing, muttering, babbling and hissing over militant noise-music that’s as much Orwellian hate-speech as it is future-fascist patriot song. Against the backdrop of such hostility, it’s hard to tell if Vega’s intermittent cry of, “This is your show!” is altruistic or, in fact, subtly sneering. Because what I hear is, "You got what you deserved."

The screens behind him dissolve through American iconography – flag, dead-eyed marine, corporate signs, missiles launching, happy family, and then the technicolour silhouette of a woman attempting to self-crucify. “Destroy destroy, yeah yeah” gargles Vega, as the music readjusts its rhythm by a mere half beat to lock into a trance state. The car-sized proto-Moog left-of-stage fires on all cylinders with a thunderous four-beat. Men bow their heads, kids down the front are dancing. A lady to my left closes her eyes shut tight. I look up as behind me the strobes are transforming the uppermost galleries into a faltering vision of faceless dummies, above them the stormy night sky of the hall’s strobe-fired ceiling. It’s overwhelming. What the conservative American music press never understood was that Vega’s art has forever involved taking on the form of the very things we fear the most, so as to better expose the true horror of the matter. So what at first looks like B-movie, boy-punk shock tactics is actually the highest form of parody, because in Vega there lies the heart of a moralist. Suicide put to shame the various luminaries of today’s industrial set and their juvenile misanthropy.

Finally the men take to the stage together to the sound of rapturous applause. Vega, his chin fixed with black tape giving the effect of a gaping hole, or a skull without jaw, or a face frozen in a scream, turns to the fawning crowd and slurs a good old New Yorkan, “Aww fuck you.” It seems old habits die hard. But there was something you’ll not see very often if you trawl the videos and photos of Vega online – above the tape hangs a wide smile. The duo are having a ball, enjoying fully their victory lap in these grandiose surroundings and finding it extremely funny that a few thousand suckers would voluntarily pay to see this horrible shit. They spend the first ten or so minutes bickering like old biddies in a park or laughing wheezily over technical hitches. Rev hams up his satanic Elvis schtick on the synth, a superstar in his own mind, or takes regular peacock-ing strolls around the stage, prowling like an antsy hood waiting for his man. Vega, meanwhile, stands sentry and contemplates the strange world beneath him.

This goes on until they finally find their groove, and get down to the serious business of doing what Suicide do best: pumping adrenalised anxiety through your veins. Hardcore noise compositions, powered by the Moog’s gargantuan beats, give way to Suicide standards like ‘Jukebox Baby’, as death rattle & roll direct from the heartlands of weirdo America mingles with nightmare-farce electro-boogie to send the crowd into fits of ecstasy. At this point the bottom-right quarter are up out of their seats while a couple of attention-seeking dickbags find their way on stage. The duo barely register the invaders, of course. What’s a couple of knobs to men who once faced the business end of a hatchet when playing live? The set then escalates into pure techno, a genre which seemed every bit the logical next step for post golden-era Suicide. Turbo-fied, ticking-clock techno, to be exact, spiralling upwards as the screen shows an accelerated phantom-shot of train tracks being eaten up by speed, to match the track’s locomotive thrust. Rev is in the moment, lost in music. But Vega, well, he is tired. So very, very tired.

Death has always haunted the music of Suicide, but tonight the subtext seems all too literal. As we near the end of the set, the waning Vega who in 2012 suffered both a heart attack and a stroke becomes increasingly erratic, disengaged and remote. Rev gently wills him on: “C’mon baby, one more time”, “C’mon pappy, help me out”, but the 77 year old, hobbling around stage with the aid of a gold-topped sceptre, seems more interested in sitting on the wooden throne set out for him behind Rev. On several occasions he escapes out the back and leaves the synth player to carry on alone, while, despite Rollins helping out on vocals, ‘Ghost Rider’ is essentially aborted mid-song. Either it’s that he can’t go on or somewhere deep inside that rascally head of his Vega is reeling against the occasion. Either could be the truth. But before the encore of ‘Dream Baby Dream’ (featuring an Gillespie mugging embarrassingly) – at which point Vega is beyond performance – he has just enough strength left to stand opposite his lifelong friend for the duration of ‘I Surrender’. One of the act’s many Elvis-informed, disarmingly sentimental, possibly sadomasochistic love songs, tonight the bubblegum synth-ballad is re-purposed as a duet between two old boys for whom time is no longer a luxury. Not since the footage of ‘History Lesson Part 2’ in Minutemen documentary ‘We Jam Econo’ have I seen such a truer expression of fraternal love between band mates. “I surrender,” coos Rev to his friend “…to you, baby.” “Fuck you, Marty” Vega replies.

A scream that held a mirror up to the true consequences of war on the American psyche, on the infamous ‘Frankie Teardrop’ Vega let fly with a final blood-curdling howl that echoed through art to this day. Together, in the face of persecution, condemnation and blank indifference, the duo held that cry of moral horror for over 40 years. But it’s time now for Suicide to stop screaming.

“When the Jews were shipped off to the concentration camps, to Dachau, Auschwitz or Treblinka, they would arrive and there would be a beautiful station and they looked like quite nice places. But then they’d walk past the nicely painted walls through a door right into hell. And that’s exactly what Marty and I were doing with Suicide: we were giving them Treblinka."

Alan Vega, The Jewish Chronicle, 2008