“Every sentence comes directly at you.”

This phrase used by Steve Aylett to describe the prose of his fictional author Jeff Lint also sums up his own writing to a T. Jam-packed with ideas that fly like cerebral machine gun fire, a relentless assault of dazzling literary fireworks – confrontational, often violent, and really freaking hilarious – one could easily spend all day musing on just one line of Aylett. The accumulation of these over the course of a novel, or even short story or comic, is impressive indeed, and makes Aylett’s oeuvre a vast garden of bizarre delights one can repeatedly wander around in order to find vivid new delights.

Next week marks twenty years since the book Lint first crash landed into our unsuspecting hands, a culmination of Aylett’s curious worldview in the guise of a fake literary biography. Aylett portrays Jeff Lint as a singularly creative force of nature. Incomprehensible and infuriating to most – pointing at things with his elbows, relentlessly writing about bellies and jelly – Lint is also a Zelig-type figure, present at major events of 20th Century literary and cultural history. Hanging with Kerouac and Burroughs, Lint is shocked at how much Benzedrine they’re taking and asks “an eminent flu specialist to call at the apartment”. He pens the ‘Flirting With McCoy’ Star Trek script and “wholesale defect” children’s cartoon Catty & The Major, as well as recording the Captain Beefheart-esque The Energy Draining Church Bazaar album with 60s psych-rock band The Unofficial Smile Group. Then there’s Lint’s Magic Bullet Theory, which sees him posit that the projectile that killed JFK was the same one fired by John Wilkes Booth at Abraham Lincoln which then traveled around the globe for the next 98 years taking part in every major political assassination. Ideas like these proliferate across every page.

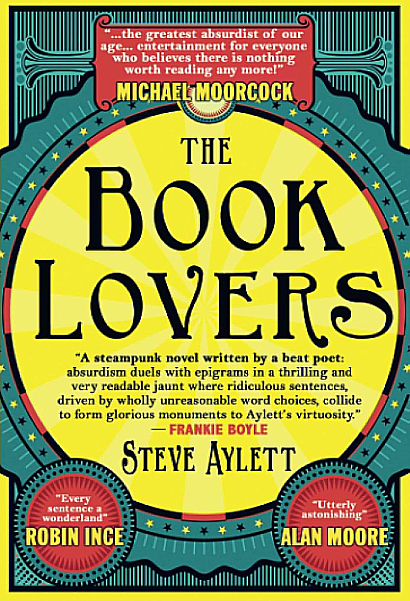

The back cover of Lint features high praise from both Alan Moore and Michael Moorcock, and blurbs from these two luminaries would continue to adorn Aylett’s books from then on, picking up further accolades from the likes of Grant Morrison, Stewart Lee, and Robin Ince, to name but a few.

Also celebrating an anniversary this year is 2015’s Heart Of The Original, a new edition of which was released in April. This treatise on creativity opens with an epigraph from Jeff Lint: “Originality irritates so obscurely you may have to evolve to scratch it.” A wonderful example of Aylett’s pithy and unique way of putting things. The opening line of Aylett’s latest novel, The Book Lovers, is another: “A book is like you and me – glued to a spine and doing its best.”

“I was very into originality growing up. And very demanding of the books that I read. I really wanted them to deliver something I hadn’t had before. I ended up writing my own stuff partly to provide that.” After surviving the “complete wasteland of the 1980s”, Aylett began publishing short stories in the early 90s, heading into books with 1994’s debut collection, The Crime Studio. By the time Slaughtermatic came out four years later, those in the know were being treated to something quite special.

But large scale popularity continues to elude Aylett, despite his having written some of the most interesting, inventive, and funniest books of recent years. Perhaps this results from not so much a refusal to play by the rules as being constitutionally unable to do so. “I always have to entertain myself as I go along. I’ve tried once or twice to write books which I’ve conceptualized ahead of time – ideas that people would understand and might want to buy – and I did about a page and a half before I lost interest. It felt like I was starving to death. There was no substance there. If it’s not coming from a place of genuine enthusiasm, then it’s not gonna have the juice.”

Another litmus test is Aylett’s synaesthesia. “An intense overlapping of the senses,” is how he explains it. “In my case I see music and ideas as dimensional structures and sometimes flavours. The shape will be colourful and give off energy if it’s interesting. If there’s a hole in the idea, there will visibly be a hole in the image.”

With such a fertile mind, it is no wonder Aylett has produced so many works of exceptional quality. So strap in as Steve takes us through ten of his best.

Slaughtermatic (1998)

Steve Aylett: Slaughtermatic was me going into Beerlight, a city where crime is the only remaining form of expression. It was giving the side-eye to cyberpunk, if a character was in some sort of virtual reality they would begin to sense it by the fact that they started to feel unaccountably bored. Because by that time I was bored by the subject and that was the only way I could write about it at all. Back then I had a lot of violent gun fights going on in the Beerlight books, and even at that point I was already like, ‘Well this only does one thing, so how can I make this interesting for me?’ So I started to talk about these sentient guns – guns that had a personality or a philosophy or that meant something so that when there was a gunfight going on, it was like a philosophical exchange, it meant something rather than people with guns just going ‘bang! bang!’ I was trying to amuse myself as I went along, so there’s a whole bunch of ideas going off all the time as well. Not quite at the density that I managed to do later on, but it was a start. I know people saw Slaughtermatic as being extreme and extremely violent but as far as I was concerned it really wasn’t. It felt like what life was like, even at the time.

The Inflatable Volunteer (1999)

SA: Slaughtermatic was really well received, like a little 90s phenomena. If I’d just carried on creating Slaughtermatic 2, Slaughtermatic 3, I probably would’ve done really well [laughs]. By the time I did that with Novahead, it was too late. What I did do was… The only time I ever recommend a kind of writing manual to anyone is Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down The Bones. Basically you’re supposed to sit down for an hour every day and just write, whether you’ve got any ideas of not. I definitely don’t do that, but I briefly did during that time and The Inflatable Volunteer is the result. It’s probably the most off-the-wall thing I’ve done. I just about managed to put a kind of structure on it by doing that framed narrative thing, stories within stories. It’s almost like a huge off-the-wall stand-up routine, as in it’s a series of surreal gags. It was through doing readings for The Inflatable Volunteer and other stuff like it that got stand-up comedians coming to see me or read me, and it was through that that I ended up being invited to perform at stand-up gigs. I’m very much like an old-fashioned satirist, but there’s virtually no proper satire in The Inflatable Volunteer at all, maybe two or three lines. The rest of it is people just setting fire to their trousers and pulling the skin off their head and there’s a jelly mould underneath. There’s that guy using a stable as a kissing booth, kissing the horses… Thank god for animals, they’re just hilarious. Just the very fact of an animal is funny to me. The Inflatable Volunteer is great fun and it’s strange, there’s some really nice dialogue here and there, nice turns of phrase that I find funny for reasons I can’t even explain. That’s the best kind of humor.

‘If Armstrong Was Interesting’ short story from Toxicology (2001)

“If Armstrong was interesting… he’d plant the Chilean flag… he’d speak in seamless, uneditible profanity… he’d emerge from the capsule riding Buzz Aldrin piggyback with a horsewhip… he’d attend a press conference wearing a hat made of a human pelvis fringed with the shrunken ears of his victims. He’d say the whole trip was a waste of time…”

SA: I mainly think of this as a party piece. Just musing about what a missed opportunity it was when Armstrong stepped down onto the Moon. Because everyone was listening, everyone had their TV turned on waiting to hear what he’d say. He could’ve done or said anything at that point, and what he did say was a bit bland. So this is just a list of alternatives that he could’ve said or done. It’s like a machine gun of ideas firing off. Again, I don’t think there’s anything satirical in it, but it was short enough that I could forgive that. It’s still quite dense and funny. A really good thing to do at a reading, and it also works as a stand-up routine.

The Complete Accomplice (2010)

SA: The Accomplice books [comprising Only An Alligator (2001), The Velocity Gospel (2002), Dummyland (2003), and Karloff’s Circus (2004)] were the one time I had a big book deal. I was living in Brighton, right on the seafront, and writing those books. It was great. Retrospectively, I realise that I should’ve just hunkered down and written something really normal at that point. But it did not occur to me at the time. It was at least a decade later that I realised, ‘Oh, hang on a minute, I see now what I was supposed to have done.’ [laughs] It was this unspoken thing, and when there’s an unspoken thing, I don’t get it. So instead I gave Orion the Accomplice books and they published them, but they barely made any noise about them at all.

Grant Morrison and I used to hang out a bit back then. They came down to visit me in Brighton once and we were talking about stuff and they said, “You should be careful about what you write because it can manifest.” And they mentioned how he ended up in the hospital nearly-dying while writing The Invisibles.[As Morrison tells it in Supergods, a staph infection collapsed one of his lungs, which he attributes to “the venom of a scorpion loa” encountered during a Voudon ritual] I thought that was a load of rubbish. But these things do sometimes manifest in life. I had written about those characters in the Accomplice books working in the sorting office and then about five years later I ended up working in the post office sorting office at night with all these zombified people. And I was like, “How did this actually happen?”

Lint (2005)

SA: Coming off the Accomplice books, something really crystalised and fell into place when I was writing Lint. I really do like to cram as many ideas in as possible and get into a situation of richness, which is good for me, in my life, and good for the writing. Richness, on all kinds of levels. Lint ended up being a way of doing that. I was in London sitting on a park bench reading a Philip K. Dick biography and thought, ‘What if I wrote one of these, but instead of this, this?’ What if there was this writer who just wrote what he wanted? And unfortunately it did kind of become a blueprint for my career [laughs]. A series of things that don’t really take off, or that have some sort of disaster associated with them.

Looking back on it twenty years later, I really love Lint. It’s such a rich little environment to roll around in. It just delivers all the time. And if you’re into that humor, then it’s a treat. It’s got stupid stuff, stand-up-ish stuff, satire, poetic stuff… it was great to create a vehicle where I could do that. I talk about Jeff Lint’s writing where every sentence comes directly at you. I really like that. It means that I’m into it. It’s such a high, being in that idea-space, it’s like a drug for me. And also with Lint, it carried on, with The Caterer comic and that zero-budget movie.

The Caterer (2008)

SA: Grant Morrison also told me, ‘You should write comics. You only have to write a few words and it’s a whole page, the artist does the rest of it, and the money is great.’ The character of The Caterer originally cropped up in Lint. I was creating fake documentary evidence to go in the picture section in the middle of the book and I made two or three pages from Lint’s The Caterer comic. It made me laugh so much, I thought why don’t I just do a whole issue of this? I was crying with laughter at times. I remember talking to one of my sisters, trying to explain what I was putting together, and I couldn’t even speak I was laughing so much. It’s just so [laughs] so stupid, and so sideways. And it was the first time this type of character crystalised for me. The Caterer is this grinning blond jock who is really full of himself, though no one around him is impressed. It’s almost like he’s got this secret joke going on inside him all the time, one that no one else understands. But he’s oblivious and impervious to other people’s regard or opinions. There’s this light of self-regard beaming out of him and you never find out why [laughs]. You wouldn’t like him in real life. But as a fictional character, he’s incredibly entertaining. I can’t even explain why it’s funny. It’s partly that there is something inherently funny about someone going off on some big routine and another person just standing there completely straight-faced, not reacting at all. Although I still don’t really know why that’s funny.

Rebel At The End Of Time (2011)

SA: I can’t remember how I originally met Michael Moorcock, but I met him several times and we’d hang about in London occasionally, and at some point along the way, he suggested collaborating on something. We went back and forth with ideas and it just wasn’t working. I’d suggest an idea and he wasn’t into it, or he’d suggest an idea and I wasn’t into it. Then I mentioned I’d been reading one of his End Of Time books and he said, ‘Why don’t you just write one of those?’ So it’s not a collaboration but it’s in a setting that he invented, and about half the characters are his. It ended up just being a really good fit, somehow really working. Because those characters are florid, and visually the setting is quite surreal, I could get up to all kinds of mischief with it. A really good experience, I actually enjoyed it. I didn’t feel like Moorcock was looking over my shoulder or anything. And I liked the End Of Time books enough to just be able to go with it.

Heart Of The Original (2015)

SA: I was coming up with a lot of dialogue which wouldn’t work with either a character or a fictional narrator saying it. It’d be like, ‘Why is this person going into this diatribe?’ And there were some gags which I couldn’t find any other vehicle for. So the idea of a combination of an alternative history of culture and a creativity manual seemed like the perfect solution. I do like Heart Of The Original. It was great fun. The structure of the book looks so normal, almost like an academic history of something. But the content is something else entirely [laughs]. And I wanted to talk about originality and creativity. I wanted to talk about this idea-space that I like, and talk about it quite directly. Also it is a big rant. It’s so blatantly me with an axe to grind about various things, going off on one about them. It’s so toxically resentful, in some ways. But there’s also a lot of good gags in there. As well as some really, really strong satire, in the old-fashioned sense. It hails back to the tradition of ‘the man of letters’, the tradition of the essayist. Stuff like William Hazlitt, who was a contemporary of Shelley and Byron. It’s an old genre, but it’s so unfamiliar now that people didn’t really know what it was. Heart Of The Original is dead old-fashioned in some ways, in terms of structure. But when you get close to it and see what’s actually in it, you realise, no, it’s not that at all. It’s radioactive with inversions. I like the idea of colours that have been turned inside-out so they’re a colour that you’ve never seen before. And the book really is that Jeff Lint thing of every sentence coming directly at you.

Hyperthick (2022)

SA: It’s great when a bit of writing or something comes out of enthusiasm, rather than any kind of strategic planning. When it comes out of personal enthusiasm, with you just really laughing to yourself and getting off on the mischief of the thing, that’s when what you make is richest. Things like Lint and The Caterer, and then my most recent experiences of that were Hyperthick and The Book Lovers. For the last several years I’ve let go of any possibility of being a kind of ‘big name’ well-known writer [laughs], which was a dream of mine at one point. But I’ve finally let go of that, for the good of my health. It’s an amazing experience to sit and create something that you’re really into, and having only a slight regard for how it will be received. Mainly just, ‘Oh my god, this is really good, I really like this’. It’s beautiful doing that.

I absolutely love Hyperthick. A lot of the stuff I started off in The Caterer, I like to think I perfected in Hyperthick. I loved the experience of doing it. Even though it was difficult, because things kept happening to stop it from coming together. Like computers bursting into flames. At one point I was in a building that whenever the heating turned on, the computer froze. And the heating was on a thermostat so it would click over every five minutes. And then at the end of Hyperthick there’s that last panel where that character who is supposedly me falls off a cliff. The day after I did the artwork for that panel, I fell off a rock and broke my leg. So it’s another one of those things like Grant Morrison warned – be careful what you write, especially if you’re portraying someone who’s got your name.

The Book Lovers (2024)

SA: I should stop going on about the 80s because it was such a terrible time for me. The early-mid 80s was such a desolate, dead time. It did get very colourful towards the end, especially in England. Thank god for ecstasy, basically. People finally loosened up. The Book Lovers is set in 1886 so that there’s a parallel with 1986. I don’t know if you’ve heard the saying, ‘Nothing happened in 1986’? Nothing happened in 1986. Except people sitting around listening to Phil Collins and the solo work of Feargal Sharkey. It was a terrible, terrible time. I spent the whole of the 80s immersed in the late 60s, it was the only way I could keep any juice flowing through my veins at all. It was a terrible dead decade. So in The Book Lovers I was using the 1880s to talk about the 1980s. That’s why you have characters saying, ‘Oh, do you remember back in the 60s?’ as in the 1860s. I was talking about how easy it is to completely shallow out a culture. And you can do it quite quickly as well. To almost a Soviet degree of shallowing things out so that there’s almost no spiritual sustenance for anyone. There was stuff going on, obviously, if you really really looked for it. But you really had to look for it. I remember in the mid 80s listening with such gratitude to stuff from 4AD, like Cocteau Twins, so that in the middle of this vacuum there was this juicy, gem-like stuff. And she wasn’t even singing in any real language. Just this incredibly baroque rich stuff. God knows how I found it.