"I had never seen anyone play like that before," Henry Rollins has written of the first time he watched Black Flag, at New York’s Peppermint Lounge in March 1981. "It was like they were trying to break themselves into pieces with the music."

Rollins, then a 20-year-old ice cream store clerk called Henry Garfield, thought he would like to break in that way too.

By summer’s end he had his chance, when the rawboned crew of Black Flag took him aboard as their new singer. So began a singular career that established him first as the posterboy of American hardcore punk, then one of its gravediggers, then, at the time of the underground’s great surfacing, a credible and willing ambassador to the mainstream.

With a band behind him, Rollins travelled to obscure precincts of the U.S. and far-flung locales across the sea to minister to their disaffected. His congregants found their private pains reflected in his own agonised condition, and before them he testified, night after night, at a volume to trouble God in heaven for neglecting His damaged handiwork.

Some disputed him along these stations. Skinheads torqued his testicles. Surfers burned his legs with cigarettes. Pretenders sucker-punched him in dressing rooms. He endured these and other indignities and repaid them only so often. Wherever he went, the lawman’s bilious shadow was never far behind.

Rollins’ body, fortified with heavy weights and tattooed totems, became a vessel for the message of his music, which is that there is nothing glorious about being broken but there is dignity to be found in the bearing of it and consolation in the knowledge that it’s not borne alone.

Or that’s not what he meant – but how else to account for all the people who credit him with saving their lives? What if the man who set out 40 years ago to annihilate, to starve, to burn, to search and to destroy, was on a mission of relief the whole time?

Rollins turns 60 this month.

These days, he’s liable to recount his past dust-ups and ego-trips with a penitent’s bowed head. He has always been self-deprecating about his contributions to music. The bar set by the first three vocalists in Black Flag ensured that a fierce need to measure up was present in him from the start, and he is quick to cite his indebtedness to collaborators. His claim was never to a superior talent, only a superior work ethic – a commitment to give it all he had, all the time.

It’s this humility that makes Rollins a somewhat unreliable witness to the quality of his own work, despite all he’s revealed of himself on stage and in print.

Don’t forget either that for years he was a polarising figure in music: a narcissist in the mold of Jim Morrison or Yukio Mishima, it was said, who combined a retrograde machismo with a politically-dubious (if prescient) ambition to turn himself into a brand. A psycho and a sell-out, in other words. ("To understand why I hate Henry Rollins," Lois Maffeo once wrote, "you’ve got to understand how close he comes to being our generation’s Ayn Rand.")

And it is undeniable, as a critic once wrote of H.L. Mencken, that Rollins has been burdened with some admirers "drawn more to the frozen model of his manner than the warm example of his intelligence." The discourtesies he slung to nervous interviewers and other hapless trespassers seem to genuinely weigh on his conscience. He is no stranger to the suggestion that his work represents an especially vigorous inquiry into the violence and self-loathing that are the birthright of white American men, and he has worked harder to sweat out his toxins than the music industry – or any other – has ever expected of its tough guys.

The truth is that Rollins has never been exactly the man that his fans or his critics would have him be. His music – not to mention the diverse portfolio of Rollinsiana that includes publishing, acting, television presenting, spoken word, disc jockeying, and much else – proves he’s too true to himself to stand idly on anyone’s pedestal, or in their pillory, for long.

It follows that he politely declined an interviewer’s request to talk about the list of records below. Who could blame him? At 60, the least he deserves is peace and quiet (and perhaps a cup of slippery elm tea).

But before Henry Rollins is enshrined completely, let the following music sound a warning to any who’ve forgotten or never knew what a vital and volatile presence he was in the first place. To become the sagely, affable man he is today, he had first to be the man of these ten records.

And that man, my friends, was not one to be trifled with.

State Of Alert – ‘Gonna Have To Fight’ from First Demo 12/29/80 (2014)

The U.S. Naval Observatory is a heavily-guarded complex where the Vice President lives with her family. Its grounds were also the unlikely location of rehearsals by Rollins’ first group, State Of Alert. (The drummer’s father was an admiral.) Idiosyncrasies like this were the rule in Washington, D.C.: this was the scene ignited by a visionary group of Black men, Bad Brains, and sustained not by Rimbaud aspirants but the children of bureaucrats, journalists, and military officers.

‘Gonna Have To Fight’ is a window into the world of a young man who has fully accepted the violence that his adopted subculture invites from off-duty Marines, Southern Maryland rednecks, and the like. It’s self-defence he’s urging, yes, but you can hear in the voice that this kid has internalised the words of Mick Jones: "And if I get aggression, I give it two times back."

Black Flag – ‘Police Story’ from Damaged (1981)

Rollins added his signature to Black Flag with ‘Rise Above,’ a song a mother could love, but today it’s ‘Police Story’ that sounds the most potent on their debut LP. Each of the three vocalists before Rollins cut versions of it; only this one, barked into the dirty cyclone of the band’s two-guitar lineup, meets the frantic resentment of the lyrics: "Understand we’re fighting a war we can’t win/ they hate us, we hate them/we can’t win."

The Los Angeles Police Department really was fighting a war, and while hardcore’s cultural insurgency was a negligible theatre by comparison, surveillance, harassment, and even imprisonment all marked the band’s history in indelible ways. It’s a mistake to assume that Rollins’ antithesis in the 80s and 90s was the fey man – your Calvin Johnsons and your Stephen Malkmuses. The real AntiRollins was the American police officer, malicious and implacable.

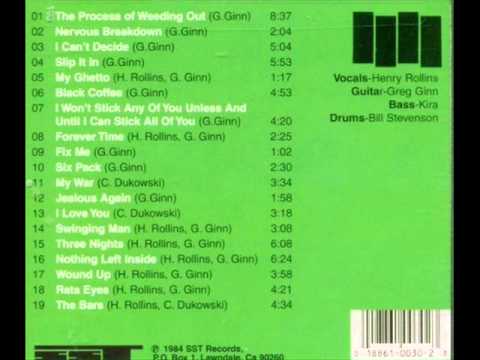

Black Flag – Side Two of My War (1984)

In the right company, the mere phrase "Side Two" amounts to a secret password to let others know you share a certain hardiness of spirit – the implication being that, should some crisis unfold, like a skyjacking, you can be counted on to return the charged glance of a co-conspirator with resolve.

More simply, the second side of the second album by Black Flag is revered for the innovation of its sludgy, desperate 19 minutes. A point-blank influence on grunge, Side Two is not for everyone – it was not for the slam-dancers – but its unremitting heaviness, including Rollins’ performance from the belly of his own beast, make it essential listening.

Black Flag – Live ’84 (1984)

In the nine months leading up to the San Francisco date captured on Live ’84, Black Flag played nearly 70 shows and cut three studio albums. To really reckon with the scale of the band’s achievement as a live act, you have to look to documents like this one. The sheer exertion put into this day’s work – which features the most durable of the band’s fifteen or so lineups – is incredible.

Rollins’ account of his time in Black Flag, Get In The Van, is somewhere between On The Road and Apocalypse Now: a harrowing, hand-to-mouth sojourn through the parts of Reagan’s America where sunshine never reached. Why did they do it? Even now, holding artefacts like Live ’84 up to the light, it’s hard to believe the answer could be so simple.

Rollins Band – ‘Do It’ from Do It (1987)

After Black Flag folded in the summer of 1986, a brief interim of experimentation resolved into a new band and two releases in 1987: the Life Time album and Do It EP. Both were produced by Rollins’ close friend Ian MacKaye, who was grasping for his own next rung with the newly-formed Fugazi.

Originally recorded as a B-side by Ladbroke Grove insurrectionists The Pink Fairies, ‘Do It’ was uncannily suited in form and content to the Rollins program. It could be his ‘(Theme From) The Monkees’. And compared to the later, ganja-befogged studio productions of Black Flag, Rollins sounds like he’s standing in the same room with you here. Terrifying.

Rollins Band – Hard Volume (1989)

Don’t mistake the liminal place of Hard Volume in the Rollins catalogue as a sign of its insignificance: this is an album of back-to-front scorchers, a point of arrival as much as a stepping stone to the bluesier, funkier sound that would elevate Rollins Band to commercial success in the 90s.

He would never sound quite so abject on record again. Listen to ‘Planet Joe’, for instance, and you’ll want to dispatch an unarmed crisis response team back in time to connect this man with local resources. Look out also for versions of the album capped by ‘Joy Riding With Frank,’ a 32-minute jam inspired by Blue Velvet and built around The Velvet Underground’s ‘Move Right In,’ which Rollins and guitarist Chris Haskett had been weaponising for years. It’s a head-banging, ass-shaking feat of musicianship and discernment.

Rollins Band – ‘Low Self Opinion’ from The End Of Silence (1992)

From the funky stew of 1992 came ‘Low Self Opinion’, the first of something like a hit. Rollins Band recorded The End Of Silence on the heels of the inaugural Lollapalooza tour and delivered its righteous reprimands just in time for the moment of alternative rock, slackers put on notice. It’s the same group but different, the rhythm section of Sim Cain and Andrew Weiss having built a summer home in the pocket since the late 80s. Rollins sounds more deliberate, too – shifting, as his simpatico peer Michael Stipe had a few years earlier, into a clearer and more powerful register.

An extremely bleak period in Rollins’ personal life tempered the success of Silence. He might fairly have cashed in his chips and spent the rest of the 90s as a book publisher, but instead he pressed on (and published the books anyway).

Rollins Band – ‘Liar’ from Weight (1994)

It can’t be a coincidence that Rollins’ film career took off around the time the Anton Corbijn-directed video for ‘Liar’ received heavy circulation on MTV. It’s the best-known of all his songs, but it’s also the most performed, with the cooing, Isaac Hayes-like verses sowing a breadcrumb trail to one of the era’s truly monster choruses. That laughter near the end like the sound of the Devil triumphant… The song is a hoot from start to finish.

‘Liar’ became a pop cultural touchstone of the mid-90s and led to a Grammy nomination and a rattling rendition at the awards show. The band lost its category to Soundgarden, but Rollins himself won a little horn for the audiobook of Get In The Van. Who else could enter the Recording Academy in the guise of Satan’s valet and leave in a class with John Gielgud and Maya Angelou?

Various Artists – Rise Above: 24 Black Flag Songs To Benefit The West Memphis Three (2002)

It’s fitting that this remains the last studio album Rollins has cut as a musician: he comes full circle here, applying the sum of his history, skill, and clout to getting three poor boys out of jail. The guestlist is an ecumenical jamboree spanning Lemmy and Iggy to Ice-T, Tom Araya, and Black Flag veterans Kira Roessler, Keith Morris, and Chuck Dukowski. Fair-weather fans may find their mileage varies, but these versions rate pretty high thanks to the coherence of Rollins’ production and the backing of Mother Superior, the powerful third iteration of Rollins Band.

Beyond a testament to the influence and durability of Black Flag’s music, this record raised the curtain on Rollins’ third act: a turn away from actually being a musician and toward a thoughtful engagement with what the responsibilities and possibilities of having been a musician might be.

Ruts DC – ‘Music Must Destroy (feat. Henry Rollins)’ from Music Must Destroy (2016)

Rollins has embraced his emeritus role, boosting new bands while working across various mediums to preserve and animate the legacy of punk. It’s a version of longevity as service. His involvement with the re-formed Ruts is case-in-point; he’s barely in this song. If he plays now, it’s for love of the game.

Music must destroy: isn’t this what Rollins’ journey bears out? Some music can break parts of you that might need to be broken – not so that you bind your wounds with nihilism, black magic, or intoxicants, but so you have the chance to regrow yourself stronger, to make room for your mind and even your heart’s abundance to increase. Don’t snicker: Henry Rollins broke many times over for that chance. The breaks were not always clean ones, he will be the first to admit, but they delivered him here, to this hard-won seventh decade whose conventions stand little chance of crossing him unprotested.