With its tarpit drones, lurching dynamics and free jazz squalls, Caveira’s Ficar Vivo is one of the year’s heaviest dispatches from the underground. Emerging from Lisbon’s experimental music scene in the early 2000s, the group has gone through various incarnations with guitarist Pedro Gomes at the helm. Active since 2015, the current line-up features two of the finest young players in Portugal’s improvised music scene, saxophonist Pedro Sousa and drummer Gabriel Ferrandini, alongside bassist Miguel Abras, a stalwart of Lisbon’s avant-rock underground. Fully improvised, Ficar Vivo shifts masterfully between brooding atmospherics and free rock ferocity, as burning walls collapse into black expanses of negative space.

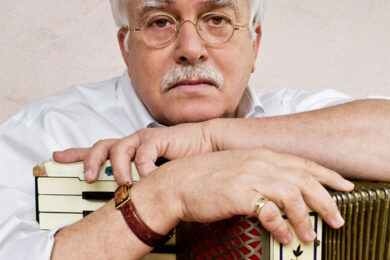

“In terms of improvised music, I’ve never been too interested in any particular circuit,” Gomes explains over a Zoom call. “I’m interested equally in free jazz, improvisation, rock and roll, the blues, African music from mostly sub-Saharan areas, and old school samba from Rio. So, I don’t try to be too non-idiomatic. I try to bring a lot of idioms from all over and make my own thing.” That openness is reflected in Gomes’ wide-ranging activities as a musician, promoter, agent and label staffer. His programming has brought improvisers like Alexander Von Schlippenbach, Peter Brötzmann, Joe McPhee and Chris Corsano to Lisbon, alongside electronic musicians like RP Boo and Foodman. He also helped found Príncipe Discos, the label that has brought the thrilling music of Lisbon’s kuduro scene to the world.

In a 2005 Lisbon scene report for The Wire, Gomes observed that the city’s “effervescent free music communities are becoming more aware of each other at an intensified rate,” with venues like Galeria Zé Dos Bois serving as hubs. Almost twenty years later, that community continues to evolve, with local labels like Creative Sources, Phonogram Unit and Clean Feed (whose experimental imprint Shhpuma released Ficar Vivo in March) helping to document it all.

OUT.FEST, which takes place across the river Tagus in the city of Barreiro, is another crucial platform for Portuguese artists, who appear alongside international acts. Gomes, who grew up in the nearby city of Setúbal, helped programme the festival for its first decade and remains a strong supporter. “I think it’s one of the most interesting music festivals in Europe for underground music of all kinds. I think it’s incredible that [it takes place in] a city like Barreiro. It’s very much an industrial, working class city. It’s very difficult to do something like this and to establish it as well as they have. Playing for the people is what we want. Not to play for rich folks. We like to play for sharp shooters, regular folks.”

Although there are plans to take the band on tour, for many years Caveira was a “militantly local enterprise.” Gomes has made a point of representing Portuguese culture in the face of globalisation that has seen many of the country’s assets sold to foreign investors. “I made a stand of writing everything in Portuguese,” he says of the album and track titles. From its recording through to its manufacturing, Ficar Vivo is a homegrown affair. “The designers are Portuguese, the sound engineers are Portuguese. The mastering was done by veteran sound genius Tó Pinheiro Da Silva. Portuguese pressing plant, Portuguese label, Portuguese liner notes by Sei Miguel.”

Under-recognised outside Portugal, Miguel has had a profound influence on Lisbon’s free music community. Since the 1980s, the mercurial trumpeter and composer has led bands featuring internationally recognised players like trombonist Fala Mariam, saxophonist Rodrigo Amado and guitarist Rafael Toral. Gomes has appeared on several of his recordings, including 2011’s stunning Turbina Anthem, where spare pocket trumpet nocturnes are ravaged by bursts of static and metallic shards. “I don’t know anybody like him worldwide,” Gomes reflects. “Sei has incredible information about the arts, about the written form, about music, and he has his own system of notating techniques. He doesn’t like his musicians to talk too much about these methods outside of the intimacy of the group work, but he basically works with a poetic written form in order to organise one’s individual expression and then he orchestrates that within group formations. He writes down how he views what you already do, and he starts from there to help organise new techniques for you. It really helps people structure themselves on a musical vocabulary level, which I find quite incredible.”

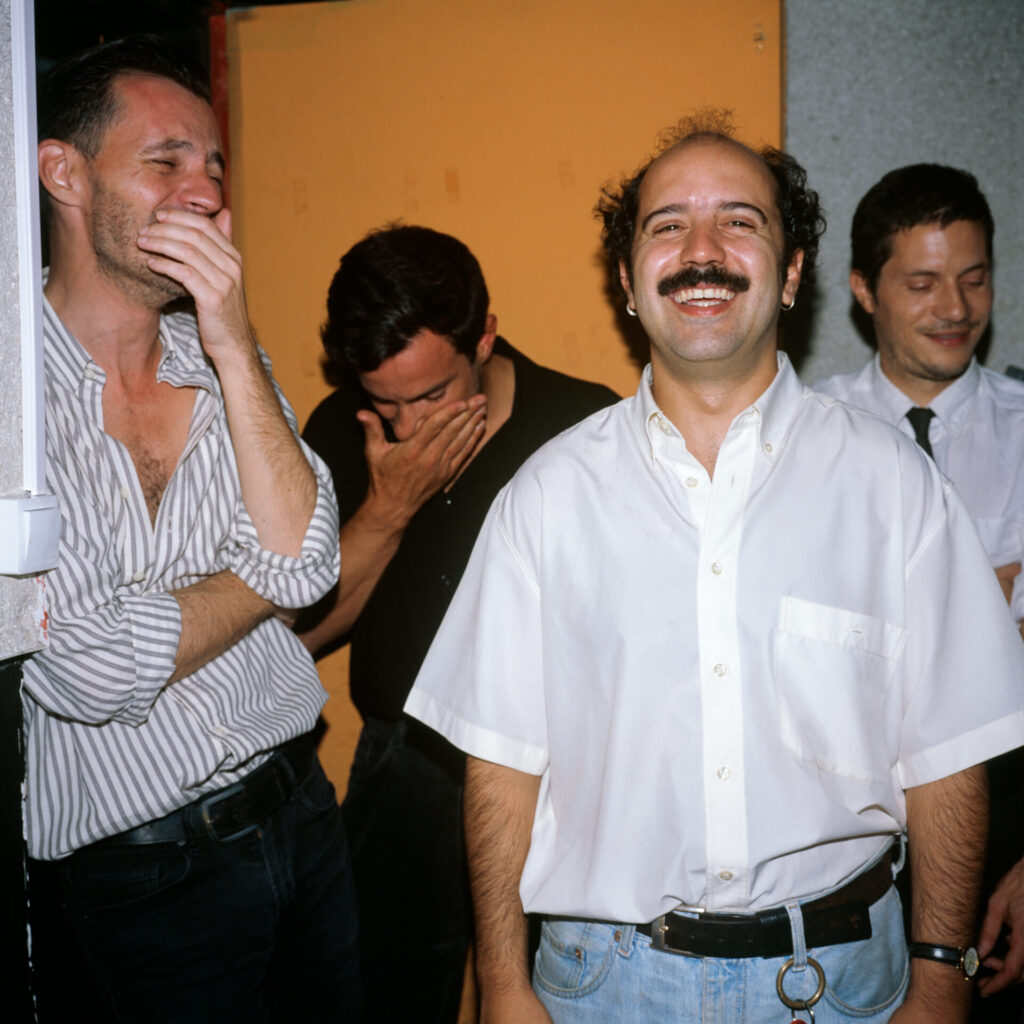

For many years, Caveira was primarily a live outfit, with its releases limited to small-run CD-Rs. In its original trio formation with Gomes and Rita Vozone on guitar and Quim Albergaria on drums, the band performed with Damo Suzuki in Lisbon and toured Europe with Comets on Fire. After a few years, the trio began to run its course, with Albergaria moving in a different direction musically. In 2011, Gomes and Ferrandini began playing together as a duo, so when it came to reconfiguring Caveira in 2012, he was the obvious choice. Sousa, his peer and a regular collaborator, followed three years later. “The first time I heard them, I was absolutely blown away,” says Gomes. “It was the first micro-generation after mine, a generation of new players that I thought were just something else. They kind of arrived fully formed, playing as a sax and drums duo. They come from more of a jazz and free jazz background, but they’re curious about every kind of music. They’re not niche players. You see, our little community in Lisbon, the healthy part of it, we were all raised by very open-minded bookers and curators. So, if it’s great music, we’re up for it.”

Bassist Abras, whose background is in underground rock, had never improvised until he set foot in the band’s rehearsal room. But Gomes could recognise his potential. “I could hear he was incredibly talented as a punk rocker and poet. As a human being, he’s very interested in others. He automatically revealed himself to be a fantastic improviser.” Gomes credits Sei Miguel and Alexander Von Schlippenbach with helping him recognise the importance of maintaining a working band. “It’s developing a group language. It’s evolving together as individuals and as a band, and this is what we try to do.”

The music, he reminds us, is completely improvised. “We have some preparatory talks before playing about something we’re interested in doing or something we didn’t like the last time we played. We kind of analyse what we do, but we don’t structure anything. What we talk about is certain aspects of sound, of tonality, the dynamics of group. We try to never be predictable.”

Doing justice to those dynamics in the studio was a challenge. “We didn’t record properly for a long time because I needed to find the right place, the right technology and the right microphones to capture what we do, because we work with very intense sound pressure and very dramatic dynamics.” Gomes is keen to point out that no compression was used at any stage in the recording or mastering, all the better to capture the extreme contrasts in volume and density. “Growing up within classical music, I got accustomed to having no compression on recordings,” Gomes explains. “So you would get the pianissimo and the fortissimo, which was also why I liked Nirvana’s In Utero so much when I was a kid. I still love it. Mr Albini, who recorded it, also disliked compression as much as I do! So, I wanted to make these free rock, free jazz, explosive records, where you have all the real sound, the presence of what is being played, so nothing is flattened.”

Gomes worked tirelessly with sound engineer Joaquim Monte to find the right microphone to capture the sound he wanted. “It’s a Danish microphone from the late 1970s that’s used to measure industrial machinery acoustically. So, it’s not the kind of microphone that colours what you do. It captures the real sounds that you’re putting out of the amplifiers. We’ve always talked about high definition sounds, where we try to make our language, which can be very, very, intense in terms of sound pressure, to be as discernible as possible. We’re all very obsessive and perfectionist about sound, each of us in our different way. They gave me freedom to make these decisions. They’re very generous musicians.”

I ask Gomes about the significance of the album title. “Ficar Vivo means two things,” he responds. “It means to stay alive, to survive, right? But it also means, and to me, more importantly, to become more alive, to intensify things. A long time ago, I was reading something that John Cassavetes wrote about trying to make people feel more, to amplify emotions, amplify states of being, to make things more intense. And this very much resonates with me and this music I participate in. I try to bring more definition, more intensity, more rawness, to the music, so it becomes more alive.”

Caveira’s new album Ficar Vivo is out now. They perform as part of this year’s OUT.FEST, which takes place in Barreiro, Portugal, from 2 to 6 October. For tickets, the full line-up and more information, click here.