Kate Shilonosova is always looking for something else. Her first solo album, recently released on the American cassette label Orange Milk and already sold out in its first run, doesn’t sound like other music she’s made before and, presumably, will put out in the future. In Russia Shilonosova’s best known as the singer of the band Glintshake, specialising in a fulminating, gnashing-guitar-laden rock that evokes memories of its members’ teenage idols Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr. Three years ago, while playing in Glintshake, she released an EP under the NV alias called Pink Jungle — exciting, danceable tracks influenced by Japanese pop, new jack swing and ’90s R&B. In addition, Shilonosova’s been active in Moscow Scratch Orchestra, revisiting the experimental composer Cornelius Cardew’s ideas and performing avant-garde pieces composed by its members and 20th-century classical musicians.

This year, though, everything’s changing. On Binasu — "Venus" in Japanese — Shilonosova explores the territory of her favorites, among whom she lists Laurie Anderson, Haruomi Hosono, Tears For Fears and Ryuichi Sakamoto, in the process of it finding her own unique style and voice. Exquisite instrumentals like the opening ‘Bells Burp’, made from default Ableton bells and possibly handy for soundtracking the start of a wushu battle, are mixed with intricate, almost childish pop songs like ‘Kata’ and the title track. It’s a sumptuous and mesmerising work, at-times erratic but feeling totally accomplished.

While the album was composed in the end of 2014, it only came out less than a month ago, a week after Kate’s band Glintshake decided to reinvent themselves, writing lyrics in Russian instead of English and disemboguing into a rich tradition of local folklore and avant-garde music. We met up with Shilonosova to discuss her origins and constantly seeking out alternatives.

Who is it that’s playing in Glintshake — NV or Kate?

Kate Shilonosova: I can’t answer this question even for myself. I think there is me, and I have some characters who are parts of me, and I relive them while playing music. NV in the first place was very naive. Recently this character became more mature and transferred to Glintshake. It’s not because Glintshake’s music is different now, but because NV’s changed over time. NV for me was always venting, showing my real self, and lately things I wanted to do as NV unexpectedly started being realised in Glintshake. It simultaneously frightens me and makes me happy. The music is still different, although. The plan that I have for NV doesn’t fit for Glintshake, and it’s a good thing. Maybe it would start fitting, and that would become one massive project — who knows. I can do what I want to. But it’s an interesting thing how the image reunited and I started associating myself with my music more. It’s great for me, because in another way I would be some psycho with a dual personality.

You live in Moscow, but you once said that you still feel like "a girl from Kazan". Is it the same now?

KS: I’ll feel like this because I’ve spent most of my lifetime in Kazan. Twenty-three years — in Moscow it’s not even a half of it! But my conscious life started in Moscow, and I truly love this city. I think it experiences a lack of love, because people come here mostly to earn money. I love Kazan too, and I have many questions for the city. When I start having the same questions for Moscow, I understand that it’s becoming more like Kazan for me. Living in Moscow is like expanding into a new territory in a strategy game. You go somewhere and start having connections with this place in your mind, just like you’re opening a map while cutting trees, gathering resources, building new kingdoms. The city is becoming bigger and smaller for you at the same time.

Speaking of Japan, while participating in Red Bull Music Academy in Tokyo in 2014, you played at the same location where Bill Murray’s character sang karaoke in Lost In Translation. Was it really your first concert?

KS: It was my third solo concert, but the first one that’s ever been booked. I didn’t know that I had to play a concert as a participant of the RBMA programme, so I was just told: "You’ll be performing there for an hour." Wow. I understood I had to play at least two shows before that, so I went to Kazan and gave a secret gig to my friends. Then, in Moscow, I was suddenly offered a concert in a Wood Wood store, which was me and my friends joking around in a wardrobe. Playing in Tokyo for the first time would be just very scary.

I remember that I heard songs from Binasu on your concerts two years ago.

KS: They are old. For some musicians releasing an album is a starting point, but for me it’s more like putting a full stop in a sentence. Although I want people to listen to my music and to evaluate it, I’m completely abstracted [from it], because for various reasons I’ve been waiting for the record to come out since last August. I wouldn’t already care if anyone said this record is appalling. I hate comparing albums to children, but when it’s already out, it’s separated from you. When you’re playing it live, you are a performer — it’s not even important that you’ve also been an author, because now you have another task: delivering it to the audience.

The album itself is like a permanent search. I find something, then I enjoy it, then I think, "No, I don’t need this." For me it’s a very logical record, but even I can notice its roughness. Usually I’m torn between many things – I want to write songs like ‘Binasu’, but Pink Jungle is still alive in me. At the same time, I want to make a four-track EP with the general idea of deconstructing words, which was originally a piece for Scratch Orchestra. Last year I was very impressed by Atom™’s performance at Sónar — I can’t say that I want to compose IDM now, but I want to make a reference to it and to reconstruct it in some way. So I always move between pop music and something like this. I like Roma Litvinov’s (who records as Mujuice) approach. He’s made a record that was nearly academic, then released an electronic album and now he writes pop songs with lyrics. Everyone knows that there are three types of Roma’s music. It’s very structured, and I think it’s cool. My music is all in chaos — I’m just trying to explore the borders and catch something there.

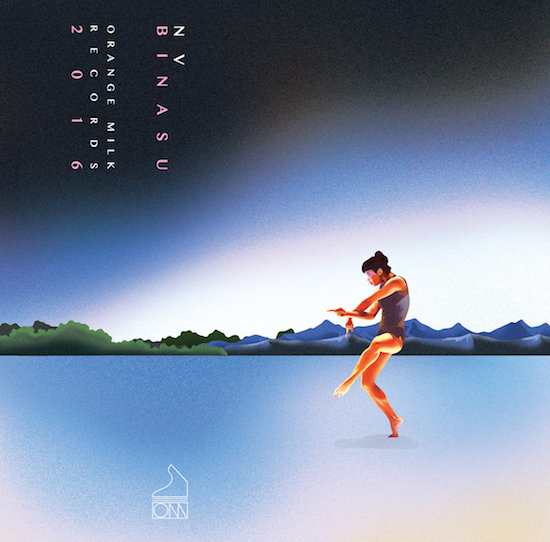

The artwork is very beautiful. How did you come up with it and why did you choose Orange Milk Records? It’s a great label, but do you think that Binasu sounds like their other output?

KS: I don’t know how people look for imprints, actually. Some of my friends just upload tracks on SoundCloud, and labels find them. Larry Gus, who I met in Tokyo, sent me a list of recommendations in which Orange Milk was the first. The contact page on the website said they had a full release schedule, but I still emailed and got a reply from the co-owner, Keith Rankin. After that Britt Brown from Not Not Fun also answered me, but he said he’d rather put out some tracks separately. I felt that the album was solid and asked Keith if he wanted to release it as a whole, and he asked, "Why, do you want to release the tracks separately?" I said, "No! Everything’s great."

I listened to other Orange Milk albums, and it’s clear that Binasu is different. But I love the atmosphere of the label, working with Keith and his artworks. Usually I paint everything by myself. I’m a huge fan of late Kandinsky at the moment and wanted to do something like that. Keith was fond of everything I’ve sent to him, then he sent me his sketches and I thought that they were awesome. "Let’s use your image!" "No, I think yours is better!" Then I told him that I couldn’t compose the final version, and he sent me his alternative, which I didn’t enjoy at all. It was before New Year’s Eve, we had to send the album in print and unexpectedly there was no cover! Suddenly Keith emails me: "Here’s another version — that’s what I thought about while listening to the music." And I see this dancing girl, and the mountains… It really hit the spot. It’s a bit strange, at once tense and relaxed, really harmonious and a bit destructive. I was shocked when I first saw it and told Keith immediately that we must use it.

Glintshake, where you’re playing with your ex-boyfriend Jenya Gorbunov, now use Russian lyrics instead of English and moves into a completely new direction. What happened?

KS: It started about three years ago, when Scratch Orchestra changed my life and way of understanding music, which became more open. Jenya was into this much earlier. We talked a lot about musicians in this new context, and I think we did grow up in the last few years, both personally and artistically. We started listening to a lot of Russian music and understood that it doesn’t exist anymore. Russian rock like Kino wasn’t completely Russian. Composers like Rimsky-Korsakov and Stravinsky employed and, what’s more important, truly loved traditional Russian folk music. Popular local music in the 20th century was mainly borrowing things from the West. Of course, everyone borrows everything all the time, and in the internet age it’s strange to talk about isolation. But the heritage in Russia is often treated very carelessly. We want to explore something that people, it seems, forgot about. I can’t say we do really great now, but in some songs — take ‘Feniks’, for example — we do. When we catch the feeling of unity with each other, it’ll cause head explosions, as in David Cronenberg’s Scanners. Earlier Glintshake were pretty embittered — now it seems like we have more self-irony. Things are trickier, and we like this trickiness, because it’s fun and there is much more space inside, especially for me if I think of myself as a character. I feel better and I can say more, and I speak more vaguely.

Binasu is out now on Orange Milk Records