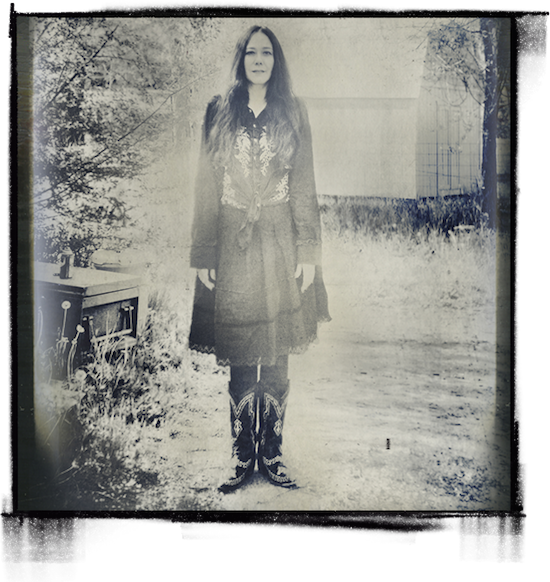

Photograph courtesy of Gary Isaacs

For over a decade now, Berlin has been idealised as the home of a free and frenzied underground culture, of wild nights of thumping beats and of ideal conditions for creative work undreamed of in other major Western cities. The best days of Berlin’s laissez-faire cultural frenzy are long since over, but if you’re one of the many people who have swarmed through the city in the past few years to sublet a cheap Friedrichshain apartment or bask in an endless night out at Berghain, you’ve enjoyed the fruits of an ecstatic umderground that Danielle de Picciotto was at the dead centre of and had a long-unacknowledged hand in shaping.

An American expat arriving in Berlin in the late 80s as the Cold War was slowly thawing, de Picciotto fell immediately into the Kreuzberg music scene around avant-noise legends Einstürzende Neubauten and their post-punk compatriots, Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds (Bad Seed Roland Wolf was her first roommate in the city). After witnessing first-hand the fall of the Berlin Wall, de Picciotto became involved in the city’s nascent underground club scene in the anarchic years when the newly-opened East was dirt cheap and largely lawless. Working at the legendary Tresor club, de Picciotto co-founded the Love Parade with then-partner Mathias ‘Dr. Motte’ Roeingh. What began with 150 people shuffling down a rainy Berlin street within half a decade had become an internationally-famous annual event drawing 1.5 million people at its peak and cementing Berlin’s reputation as the techno capital of the world.

A restless and enthusiastic creative spirit, Danielle has worked in every medium imaginable, from painting and illustration to making video art and directing documentary films (her most recent documentary, Not Junk Yet, about cult East Village artist Lary 7, premiered at New York’s Anthology Film Archives this past February). She has collaborated musically with some of Berlin’s most legendary musicians, fronting her own band (the Space Cowboys) from ’90 to ’95 and recording or performing with Die Haut and Gudrun Gut, among countless others. She has written two books, one a German bestseller. In later years de Picciotto ran a gallery that showcased some of Berlin’s most interesting artists, and organised countless events, performances and club nights before deciding to take a break from the now-infamous city whose reputation she helped shape. After marriage to Neubauten bassist and all-around sonic genius Alexander Hacke in 2006, in 2010 de Picciotto and Hacke took the radical step of packing up their belongings, giving up their house and becoming nomads. They have spent the last five years travelling, recording and performing across the world, from Istanbul to L.A.. Last month, de Picciotto released her first solo album, Tacoma, named after the US town in which she was born but where she did not grow up. An atmospheric musical travelogue, the album focuses, like most of her recent work, on her current nomadic state and, by extension, on the idea of home and on the sense of self. Fittingly enough, de Picciotto’s in L.A.’s Silver Lake neighbourhood when the Quietus speaks to her over the phone to discuss her new album, her nomadic lifestyle and those years in Berlin.

Tell me a little bit about how you and Alexander Hacke made the decision to become nomads.

Danielle de Picciotto: I had been unhappy in Berlin for quite some time. We realised after a while that we were earning all of our money outside of Berlin. And we had a really great house with a great garden, but it was always empty, so it was more depressing than good because we’d come home, and we’d pay all the money we had earned into the cost of the house and then we’d leave again. We’ve been working in this city now for 30 years and it still doesn’t generate enough jobs for us that we can actually be in our house 50% of the time.

What has the experience [of being a nomad] been like?

DdP: It’s been actually incredible. The thing is, when you’re a nomad, you have to always plan one year ahead. Because you can’t afford to get stuck anywhere without a job or a commission or a tour because then you don’t have a home to fall back on. We have to be working all the time because otherwise we don’t have a place to stay. After a while not having a home changes your perspective on things, because you don’t have that place, that safety net, where you can kind of crawl back into whenever things get rough. It changed the way we live; we had to become extremely disciplined. We stopped drinking, we become vegan. We hardly party because if you travel all the time and you party all the time, we would be dead in the meantime. So we had to completely change the way we eat, the way we sleep, the way we work, everything. It’s really crazy. It’s a really crazy experience.

And now after all these evolutions your first solo album is coming out this week. Congratulations about that. How do you feel?

DdP: Happy. I’ve been wanting to do a solo album since ’95. I had a crossover hip-hop band called Space Cowboys, and when they split up I wanted to do my solo record. And I started, but I kind of had bad luck for years doing it. First I wanted to do it with Roland Wolf but then he died [Wolf died in a car accident in 1995], and then I wanted to do it with other people, but they kind of didn’t have time, and then I was ripped off by a producer, so for years I tried and at one point I was just like: ‘OK, I’m just going to wait for the right time and concentrate on other things in the meantime.’ And it was really easy and it just kind of happened very smoothly. So I guess I waited for the right moment.

And it was recorded all over the place while you were travelling?

DdP: Yeah, I recorded it in Hudson and New York and Berlin and Los Angeles and Joshua Tree. So wherever I was when I had a little bit of time and I wasn’t touring, I would set up my little mobile studio and continue working on it.

What’s your general approach to writing music? Do you start with lyrics, chords, melodies, do you just improvise… what’s your process like?

DdP: I’ve been writing a diary since we’ve been nomads, and a part of it is going to be released as my graphic novel in August, We Are Gypsies Now, in English. I just write about what happens ever since we’re nomads all the time. So most of my lyrics come out of my diary. I wrote music just thinking of the atmosphere, not necessarily writing the music for lyrics. And then depending on the different songs I again looked at what texts I had and put them on the different songs. I did the whole thing so instinctively. I didn’t know what kind of music it was going to be actually, and when I started recording, I knew I didn’t want to do any song structures, I just wanted to do something pretty free and I ended up doing something that kind of reminded me of music that I liked when I was really small. Because my first record that I got was The Good, The Bad & The Ugly by Morricone which my father gave me, and I’ve loved his music ever since.

Why the title Tacoma?

DdP: I was born in Tacoma, but we left when I was about four months old and I never went back. So until last year I had no idea [of] where I was born, and I always had this mystical vision of it being this gold miners’ beautiful place, with this Native American name, I had this David Lynchian picture of it. And then I was at this party in Chicago where someone said, "Tacoma? That’s the asshole of the US!" I just got these really strange reactions. So I said, okay, I have to go and look at where I was born. I went there and it was a really kind of wonderful experience because it’s very poor and it’s pretty rundown, but it has this kind of Jim Jarmusch atmosphere. It’s really a small town, and everything is really slow, and Washington state has this beautiful clean air, it’s really clear, and all the colours are really crisp; it’s like a 50s movie or something. I spent two days just walking through empty streets and sitting at empty bus stations and taking empty busses. It was really magical. And it really changed something. So that was a really important experience for me and I had that right before I started recording the album.

You work in a lot of different media. Illustration, video art, music, writing… are you always multi-tasking or do you have one medium that you focus on and then move on to the next thing?

DdP: Usually I can’t multi-task. Doing all of these different things is difficult anyway, so if I really want to go into depth as much as possible, I kind of have to concentrate on one thing while I’m working on it. For instance I haven’t painted now or I haven’t done any illustration for almost a year because I was concentrating on music, and when I’m painting I don’t really do music, except I rehearse my instruments. I feel that the different media express things in different ways. For instance now that I’ve done the album I really really have the urge to paint the themes. So the next thing, as soon as I’m done doing all these music videos for the performances, I’m going to start painting again. I have a specific theme, and then I have the different media to express them differently. And then, when I’ve expressed a certain theme with all these different media to the hilt, a new theme comes.

Basically for the last five years the theme has been being a nomad. So I’ve written a book about that, and now I’ve composed an album about that, and the thing that’s now missing is basically doing a whole collection of art pieces about that. And I think when that’s done, I’m hopefully going to settle down!

You’re American by birth but you also write and sing in German.

DdP: Well that was a very surprising part of it because I actually write in English. I write my diary in English, I think in English, I usually dream in English, but then this time, for my solo album, I had a really strong urge to write in German, which surprised me, because I’d never had that before. And I think that it’s because this whole thing about leaving Berlin is such an issue in my life that expressing myself instinctively musically it kind of came out that way.

Speaking of your 25 years in Berlin, you were really at the heart of the post-Cold War art scene in the 90s and early 00s. What was Berlin like back then?

DdP: It was kind of the way I dreamed about the world being. It was like a manifestation of everything I kind of hoped life could be. It was like that already when I moved to Berlin in the 80s, but then when the Wall came down… until ’95 it was such an anarchic situation that nobody knew what the rules are or what belongs to who or what’s going to happen. Everything was completely out in the open for five years. And the amazing thing about that was that it didn’t result in riots or crime, not at all, it was so creative, people used it to be creative. And the amount of places, galleries and clubs that were initiated by different people was huge, and the quality of the things that were done was incredible.

I think that it hasn’t been as good since in Berlin, because there were no restrictions and people could just really do whatever they wanted. It was so cheap that they didn’t have to think about money. And those things combined were incredibly good for the level of art. So that was kind of heaven. It really was just incredible. It was non-stop constant. And it was incredibly inspiring. And you could just do something anywhere with anybody without any money and hundreds of people would come.

You’ve worked with everyone from Ocean Club, Die Haut and, more recently, Mick Harvey with The Ministry of Wolves and The Tiger Lillies on At The Mountains Of Madness. What do you enjoy about collaborative work?

DdP: I think that stems directly from working as a [visual] artist, because when I’m painting or doing drawings I’m in the studio alone, and you’re completely concentrated on yourself, and you can’t speak to anybody, you can’t see anybody… When I’m painting I don’t like being around people, in fact I hate it. I don’t like people to see what I’m working on, I don’t like them to see it before it’s done, I’m not somebody who’s going to show somebody something and say: ‘Do you think this is going in the right direction?’ It’s more of, I shut the door and I disappear for as long as I have to, and that can be for years. It’s kind of also the same thing with writing obviously. So I’m so happy when I can do something together with people, because one thing I really like is kind of having something happen which I myself would not do on my own, which can only happen if you’re doing it together with somebody else.

I prefer working with people especially that are completely different from me, that have a different taste, that have a different way of going about things because that way something is going to happen which nobody expects. That’s one of the reasons I was initiating exhibitions and stuff, because I would always try to get all these different artists that did extremely different work, which is not very popular with curators. I’m not somebody who thinks that you know, doing that crazy artist thing of drinking all day and going out all night is going to make me more creative. It never did, in fact it actually only made me tired. I’ve never been good at working with a hangover. But getting together very opposite kinds of people that usually would never even be in the same room and doing something together with them, that’s always made incredible things pop up.

Are there other cities you’re looking forward to exploring or planning on spending time in soon?

DdP: We’re going to be in Brighton again, which is a really interesting place. I love England anyway, I like their sense of humour and their odd eccentric sides. We’re gonna be doing another tour in the fall to present my album and my graphic novel that’s coming out, so we’re going to be touring the States and Europe. I think basically the most important thing at the moment is for us to kind of figure out where we want to settle down, because, like I said being a nomad is great, but it has this superficial quality to it which after a while I can tell is making me really dissatisfied, work-wise.

I just feel like being in the studio for a year and really working on something in-depth. I have to settle down for that, so I think that has to be the next step. And I’m really into outsider architecture and I kind of have this dream of settling down into something and turning that into some kind of surrealist universe, where I have studios to invite people to and where we can do stuff and generate stuff from there. I think the next step after being completely rootless and not having a home is kind of building your own universe.

Tacoma is out now on Moabit Records, and the English edition of de Picciotto’s graphic novel, We Are Gypsies Now, will be published in August. For full details and to get hold of the album and the novel, visit her website