To read the rest of our Reissues And Compilations Of The Year So Far click here

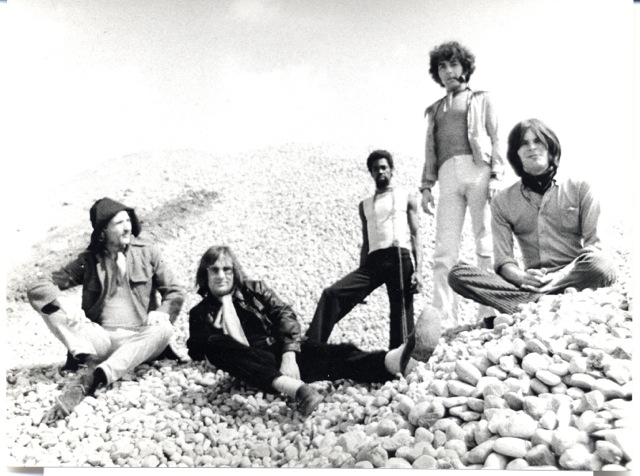

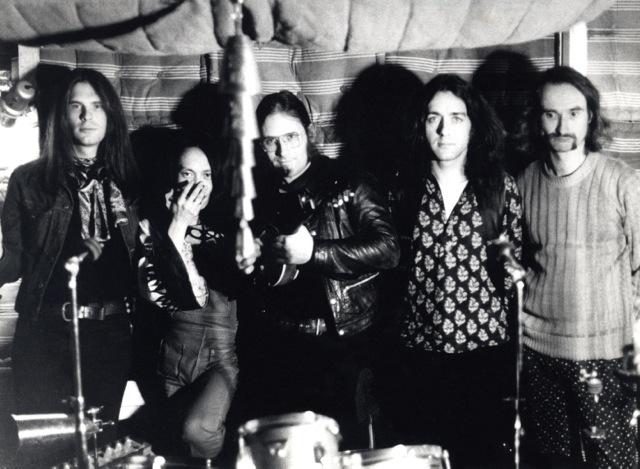

The players…

Holger Czukay: Can founder, engineer, composer and bass player.

Jaki Liebezeit: Can member and one of the most outstanding drummers of the second half of the 20th Century.

Jono Podmore: Compiler and producer of The Lost Tapes. Irmin and Hildegard Schmidt’s son in law.

Irmin Schmidt: Can founder, conceptualist, composer and keyboard player.

The background…

Jono Podmore: My first involvement was way before The Lost Tapes project had been suggested. I’d been aware of the tapes since ’98 when I had a tour of Can’s studio in Weilerswist. I first saw all of the tapes together around 2003 when my daughter was born. The full collection of tapes filled up three of those large, four drawer, office filing cabinets. A lot of it was bollocks. Tapes of radio shows, practice sessions… Quarter inch tape in those days was also used in the same way that cassettes were used, for all kinds of things not just for recording masters. The notation was total drivel. It bore no relation to what was on the tapes… mostly because they were always being reused.

Irmin Schmidt: My role was to make the choice. My job was to take this huge amount of material and choose the pieces that were worth putting on an album. After I made this choice I discussed it with Jono. In my first, big selection, there were a few pieces that I was unsure about. There were some that together we decided were really not worth it but then there were other pieces that Jono really fought for which I wasn’t sure about. So my first selection was bigger than the amount that is on the record but it would have been even smaller if Jono hadn’t fought to keep three or four extra pieces. We did that final choice together and then we had two afternoons playing it through with Daniel Miller and he totally agreed. The pieces that I had doubts about that Jono wanted, Daniel wanted too.

Jono Podmore: My life is massively intertwined with Can. Hildegard and Irmin are my parents-in-law and their daughter – my wife – is now a co-director of Spoon records. We run the mail order from our house. I was involved in this project very early on. Hildegard came up to me and asked me very formally to be involved. We obviously spend a lot of time together, eating, drinking and making merry and all the rest of it. I lived with them for a couple of years while I was working with Irmin on the opera Gormenghast. Hildegard asked me to do the editing on the basis that not only did she trust me musically and artistically but I was neutral in the whole ancient political structure of Can. She couldn’t ask Holger as that would piss Irmin off. She couldn’t ask X because that would piss off Y and so on. I get on well with Jaki. I get on well with Holger and Irmin’s family… So she asked me and I said yes.

Holger Czukay: Our system for archiving stuff was quite chaotic. We had a lot of tapes getting stored in a climate controlled room. And by ‘climate controlled room’ what I am actually referring to is the basement but the system was quite chaotic… yes.

Jono Podmore: Hildegard got the tapes transferred to digital and then sent copies of everything on CD and DVD to me and then another set to Irmin. I spent two days a week for months lying in bed with headphones on, listening to this stuff, making notes in a Word document, thinking about what could be done…

Jaki Liebezeit: I first heard about the project when Jono gave me some copies [of The Lost Tapes]. He’s teaches at the music high school in Cologne at least once a month where he’s a professor. So he gave me these copies of The Lost Tapes album when he was in town – which was quite a surprise for me.

CD ONE

‘Millionenspiel’

Holger Czukay: I think we needed to change from when we were recording as Inner Space in 1968 as at first we were just students and going in a different direction. The first of these tracks ‘Millionenspiel’ was recorded because some people wanted theme music for a TV show that was quite science fiction. A lot of people thought the show was true – like War Of The Worlds. It’s quite hard to explain though. It didn’t make any sense. This was one of the first pieces we ever recorded and I’m quite surprised at how professional Can made it sound. It was a bit more difficult when we first started playing concerts live. The concerts could be good but also they could go down on the other side. The studio we used later on was sold to the German pop and rock museum but the first studio, The Inner Space studio, I still own. It is a very good studio.

Irmin Schmidt: When we recorded ‘Millionenspiel’ we still didn’t have the name Can. When I originally approached everybody to say to them, ‘Would you like to form a group’, my idea was to bring together musicians who came from totally different fields which were all new forms of music in the 20th Century. David Johnson [flute], Holger and me came from the academic tradition of classical performers and composers. At the time this had its newest incarnation in the music of Stockhausen, who we were studying along with similar composers. And then I wanted a real jazz musician and a real rock musician. When I asked Holger if he would be interested in a group like this and he said, ‘Oh yes I would and I will bring Michael Karoli to meet you as well, he’s a young rock guitarist.’ When we met, we liked one another – he was a brilliant guitarist. So that was the idea, to cover all these fields. David was very much a new classical music composer, and after a certain amount of time, Can was turning into a rock group – even if it was very experimental and very avant garde rock group. David didn’t like the rock element that much; he thought it would stay more on the experimental side of things, like on ‘Blind Mirror Surf’. And when it became more rock he didn’t like it very much so he stepped out.

Holger Czukay: In the beginning we tried to offer our first album to a record company but it was denied, so we made a private pressing and then that private pressing sold out immediately. And that is why the record company came to us and said, ‘Perhaps you would like to make a record for us after all.’

‘Waiting For The Streetcar’

Irmin Schmidt: Sometimes we had an influence on [original Can singer] Malcolm Mooney’s lyrics. ‘Waiting for the streetcar’ was something Michael said during a performance at the castle near Cologne where we practised, Schloss Nörvenich. During this performance, Michael said, ‘Malcolm, just wait a minute, there is somebody waiting for a streetcar.’ And he just used it and continued saying it over and over again. In a way this is pop art. These lyrics are like Warhol putting Brillo cartons on top of one another. All of the sudden the banality of the Brillo carton becomes art and the banality of this sentence repeated in this context of music all of a sudden becomes something more than just a sentence. It becomes pop art. It is the same as Jaki repeating one beat for a long long time. It has the same aspect.

Holger Czukay: ‘Waiting For The Streetcar’ was one of the first recordings we ever did with Malcolm Mooney… It’s quite long.

Jono Podmore: The biggest shock and surprise on listening to the tapes for the first time can be summed up in one word: Malcolm. Not only were the tracks featuring him absolutely wicked but the reason why Can weren’t this horrible, academic, German, up its own arse collective was because they had an African American singer who lit the fuse and gave them a proper sense of grit. He wasn’t just any African American either, he was a proper artist and bonkers to boot. When we played the tapes at home my daughter, who was five at the time, would be jumping up and down singing along to ‘Waiting For The Street Car’. That was a hit in our house. When I heard that for the first time, I knew we were on to something.

‘Evening All Day’

Holger Czukay: When we had our first concert in the castle Schloss Nörvenich we were preparing for a Picasso exhibition. They wanted a band in the gallery, surrounding the exhibition but we were not experienced at all, we’d never really played together. So we started playing and Malcolm started going up and down the grand staircase in the castle and singing "Upstairs… Downstairs… Upstairs… Downstairs…" It was very much like ‘Waiting For The Streetcar’. It went on for quarter of an hour, maybe half an hour. It was so monotonous and repetitive, that even these days with repetition in lyrics and phrases [in house music and techno] people would have found his performance very odd.

Irmin Schmidt: Malcolm never discussed his lyrics, either before or after we recorded the song. Sometimes we agreed that it should be a sentence repeated over and over. Sometimes he would say, ‘I have other lyrics!’ And we would say, ‘Well, why not save the other lyric for another song!’ But sometimes he would like a lyric so much he would become really obsessive about it.

Jaki Liebezeit: The castle belonged to a rich man who collected art. He had poor artists in and there were also some classical musicians who came to stay there. He had some grand pianos that the pianists would practice on. And also a sculptor, Ulrich Rückriem, who became very famous in Germany, also worked in the castle. There was a big room that was free and it was given to us, and we made a studio there. It was a very primitive studio in the beginning. We had very little equipment but we worked there every day, and we recorded as much as we could.

‘Deadly Doris’

Irmin Schmidt: I was very surprised and pleased to find ‘Waiting For The Streetcar’. I remembered recoring the song and that was great because it’s a kind of a nice and joyful memory. Some of them I don’t remember at all like ‘Deadly Doris’.

Jaki Liebezeit: When Can started we had a little studio. One day Malcolm Mooney appeared… I think somebody must have told him to come and meet us. [It was actually Hildegard who invited him to visit, Ed] Mooney was on his way back from India where he was looking for his school. He didn’t find it because it was actually in the USA [laughs]. On the way back from India Mooney visited some countries in Europe and somebody from the art scene I think must have told him to meet us in Cologne. So one day he came to us and it was a big success… so he started singing with us and he stayed with us. The band was very fresh and we had no singer, so we were very happy to meet him.

‘Graublau’

Irmin Schmidt: My sense for nostalgic sentimentality is extremely limited… I was looking for and was very happy to find this track because I remembered making this Graublau film music because I was very much into the sound design and recording. We used short wave radios and stuff. I remembered making it and being very happy with it at the time. I rememberd that we had the idea to put it on the record once at the time but then Tago Mago came up and it didn’t find its way on this record and then later it got sunk into the archive and we didn’t find it again. So I was very happy to find this one because I remembered it so well.

Holger Czukay: "’Graublau Vogel’ was a title track for this science fiction movie which had nice colours but didn’t really have any action in it."

‘When Darkness Comes’

Irmin Schmidt: It was necessary for Malcolm to leave the band when he did. Definitely. He suffered from the situation he was in. He had an incredible fear of being drafted into the military and sent to Vietnam. And on top of that, he had an even greater fear that maybe he would get sent to prison because he’d been in so many different countries, not just Germany but India as well and there was a worry that when they got him they would arrest him for desertion. The military, I think, had already been to his New York home. He was full of fear and this troubled him a lot. Living with these difficulties in a country where you don’t know the language doesn’t make it better. You can’t express your feelings totally in a foreign language, even if we did speak English. And he got very fragile so he had to leave. He was in a psychically fragile state, which was very understandable, although we would have loved to have kept him. But it was necessary for him to go to the States and sort the whole thing – including his state of mind – out. And yes, on ‘Darkness In Mind’, this all comes out. He expresses the deep desperate state of his life for a moment. We could only help him by sending him back. Which we did and it did help him. We are still friends. I speak to Malcolm at least once a month.

Jaki Liebezeit: We only made one record with Malcolm – Monster Movie – after that I don’t know what happened to him, he had some psychological problems… maybe it was just homesickness. So he went home to the USA.

‘Blind Mirror Surf’

Irmin Schmidt: ‘Blind Mirror Surf’ was recorded in a totally different room from normal in Schloss Nörvenich. You will notice that there is nearly no reverb on it. It was recorded in quite a big room which was really just a building site. All the garbage from the renovation work being done on the building, whatever it was, went into this room. We became fascinated by the atmosphere in this room, especially in the evening or first thing in the morning with all this garbage and these old columns, and broken glass everywhere. So one day we put the microphones in there and walked over all this garbage, all this broken glass, with everyone holding different acoustic instruments like a flute and a violin and so on. And we just recorded according to the strange atmosphere in this room. ‘Blind Mirror Surf’ just wouldn’t fit on a record that we were doing and so it got forgotten about. I was quite surprised when I found it, there were three versions. I had to choose one, the other two were equally as good I think. But it was actually one long recording with pauses in between. It reflects a spooky, ghostly mood in this room full of garbage in a castle.

Holger Czukay: Around this time I was sitting with Jaki in a café and Damo [Suzuki] came along and he was making an incantation to the sun or something strange like that. I said, ‘Jaki, this man will be our new singer.’ He said, ‘Come on, are you being serious? You haven’t even heard him and you say that?’ So I went to Damo and said, ‘What are your plans for tonight?’ He said, ‘Nothing.’ So I said, ‘Do you want to be a singer in a band for a sold out concert?’ He asked would there be a rehearsal and I said there wouldn’t. And that’s what he did. And that’s what he did. And during the concert he started very, very calm but then he developed into a samurai fighter and the people got so angry that they left the venue. There was only about 30 people left in a venue that holds 1,500. But one of the people who stayed to the end was David Niven. At the end we asked him what he thought of the concert and he said that he didn’t know that it was music but he thought it was fascinating. He was very polite even though I don’t think he liked it.

‘Oscura Primavera’

Irmin Schmidt: Tracks such as ‘Oscura Primavera’ or even ‘She Brings The Rain’, are pieces which are nice in that way. Less aggressive or less complicated… we didn’t decide to make nice, less aggressive music. It just came out like that. It just happened. Tago Mago may be a very heavy record and maybe ‘Graublau’ on The Lost Tapes is a very heavy piece but we also made the record Future Days, which mostly is very light-hearted although it’s very experimental and avant garde. Because in that moment that is how we felt. And that is how life goes.

Holger Czukay: What made these other sides to Can come out? We were not relying so much on a subjective theme. The songs always came up like happenings and we left them like happenings.

‘Bubble Wrap’

Irmin Schmidt: I didn’t think Bubble Wrap’ should go on at first. I didn’t think it was good enough. As simple as that. Jono said, ‘This is a great piece of music. Have you gone crazy?’ I had some doubts about it but it was in my original selection all the same.

CD TWO

‘Your Friendly Neighbourhood Whore’

Irmin Schmidt: When we started the group, like everyone else we needed somewhere to work. We needed a room to record in and to practice in. For years I had very strong connections to the art scene because I had made speeches for painters and had curated several exhibitions of young artists. One of my gallerist friends said, ‘Look I will introduce you to my friend who has a castle in Cologne, maybe he has a room for you.’ Christoph [Vohwinkel] met us and said, ‘This sounds very interesting, yeah! There are so many rooms that are not used in my castle. And anyway I’m only there some evenings and some weekends and when we have receptions for galleries or whatever. So you can have this room.’

‘True Story’

Irmin Schmidt: So we had to convert this room to our needs acoustically. We started to work in this room. The castle also had this wonderful hallway with a staircase with an incredible… wonderful reverb, like a cathedral. Really wonderful. So we used that reverb and that is what makes up part of the quality of the recordings done in Schloss Nörvenich. Because we always had speakers outside of our room in the hallway.

‘The Agreement’

Jono Podmore: There’s a playfulness in tracks like the ‘The Agreement’ and ‘True Story’ which doesn’t usually find its way onto the Can studio albums. If you think of a track like ‘Aumgn’ and the trippy stuff on Tago Mago because they were given these portentous titles they’re taken very seriously but some of this stuff is just lads messing around. I mean, they were a bunch of stoners! I think these tracks show that they were having a laugh. There’s a lot of humour in there, which is down to a sense of fun.

Jaki Liebezeit: We made two records at Schloss Nörvenich, Monster Movie and Tago Mago. Then for some reason I think we had to move out – either it was sold, or something, I don’t remember exactly what happened… and we moved to another place in a village called Weilerswist nearby which had an empty cinema which had closed because of television – nobody would go to cinema any more in the village. So we rented this old cinema and made our studio there. The room still exists there – Holger lives there!

‘Midnight Sky’

Irmin Schmidt: Some of the songs show the rockier side of Can. There has always been the mixture of the very subtle and complex on one hand and the very direct, spontaneous and rocky on the other. That was what Can was all about – we used all of the music of the 20th Century whether that was soul, jazz, rock and contemporary classical. Maybe we leant more toward rock when we started but I don’t think so.

Holger Czukay: Can could become rock & roll, yes. The Americans like Hendrix were important to us but not so much that we became heavy metal.

Jaki Liebezeit: When we were in the studio it was more or less like playing live because in the beginning we didn’t have multi-track recording so it was us recorded in stereo and we all had to play together – no overdubbing and things like that.

‘Desert’

Jaki Liebezeit: We always started with some idea and then started recording – we never wrote anything down. So we worked it out in the studio, because we were one of the first groups I think who had a home studio – or an almost-home-studio. It was very primitive but it was our studio and time no longer played a role, so we could stay in our studio as long as we wanted. We didn’t have to pay for it like we would a normal studio. So we had time to work out some ideas and recorded until we thought it was good enough to release. So of course, with these lost tapes, it was material we thought at the time maybe it was not good enough to release or… I don’t know why it stayed in the room where all the tapes were.

‘Spoon’ (live)

Irmin Schmidt: As it turned out ‘Spoon’ became a big hit here in Germany, it was a number one [actually a number six, Ed], so we ended up playing the song live a lot of the time because the people asked for it. But we never played it like it was on the record. It was always a new creation. The creation of ‘Spoon’ could go on and on and would always be different. This is why I thought it was good to have the different versions on the album because we always played ‘Spoon’ differently live and this is captured here.

Holger Czukay: My favourite track on the album was recorded at a free concert in Cologne. It is called ‘Spoon (live)’. Can went totally out of themselves as a live band. A lot of people [students] rioted in Cologne and they were storming the buildings and smashing the windows. The City of Cologne stopped hosting these kinds of concerts for some time afterwards. So I went to the City Of Cologne and said, ‘Why don’t you make a free concert and then people will stop smashing the windows again.’ And then they let us take over this sports hall with the capacity of 10,000 people, I spent a week installing all the lines and microphones and tape recorders and especially because a film crew was expected and I had recorder switched on with only two microphones and this was what you hear now on ‘Spoon Live’. This is Can live through two microphones with no mixer or anything else like overdubs.

‘Dead Pigeon Suite’

Irmin Schmidt: With the suites such as the one that was originally called ‘Dead Pigeon On Beethoven Street’ [the name of the film it was originally written for, Ed], there are pieces in development which are very near to the final title songs, in this case ‘Vitamin C’. ‘Vitamin C’ was the title song and you find all the elements there. I’m not sure if this ended up getting used or not but it is on the way to becoming the final version. But only ‘Vitamin C’ made it onto Ege Bamyasi, which tells you something about how this music is made.

Holger Czukay: With ‘Dead Pigeon Suite’, I remember meeting with Samuel Fuller a film director. We all met him together and he was a strange guy. He had never edited a film. Well, in Cologne he was allowed to edit a film but in Hollywood he was never allowed near the editing room. He used special film editors. So he was running from one room into another and back again when we met him. He was very excited and confused. ‘Dead Pigeon Suite’ fits very well into his movie.

‘Abra Cada Braxas’

Jaki Liebezeit: I don’t remember all these recordings. It was a surprise for me to hear this material – I honestly don’t really remember it. It was a long time ago.

‘A Swan Is Born’

Irmin Schmidt: I didn’t like this one either. It is one of the pieces on the way to being ‘Sing Swan Song’. What I like about The Lost Tapes is that you have pieces like ‘A Swan Is Born’ and ‘On The Way To Mother Sky’, you have pieces where if you compare them to the final versions on the records, you learn something about our process and how this music works and develops which I like very much."

‘The Loop’

Irmin Schmidt: A loop that wanted to become a track, never quite made it and was then forgotten about.

CD THREE

‘Godzilla Fragment’

Jaki Liebezeit: Holger would edit everything we did. So of course when we recorded there was a lot of material which was just useless. Usually we recorded quite long pieces, so maybe one half of the piece was quite good and the other half not so good, then we would have another recording which was also one part good, another one not so good. We would edit the things and put the good parts together. I had nothing against editing, it’s quite normal – like in movies, and in music… it’s a legal process to do that in the studio. It’s normal… everybody would do that.

Jono Podmore: There’s stuff in some of the live tracks that hasn’t really appeared before. That ‘Godzilla’ thing of turning a polite rumination over a few ideas into a big fucking monster is something that the band have discussed doing but has never really seen the light of day before.

‘On The Way To Mother Sky’

Irmin Schmidt: After we recorded we very often made collage and montage. We edited the pieces. That was really done with Holger, Michael and me. And we three decided what the architecture of a long piece would be after it was edited. And then Holger was the one who had the craft to do the edit but the decision was made by the three of us. Jaki didn’t have the patience to listen to the tapes and say, ‘This bit would be nice there’ and so on. But Jaki had a very important role to play when we used montage because when we had done an edit, he would get really furious if we had destroyed the continuity of the groove. So he was very strongly involved in the end of making montage or collage and edits. In the end he had to be able to say, ‘Yeah, that’s ok… you didn’t destroy the groove!’ So working on the architecture of the groove was very important. Say on ‘Halleluwah’ or ‘Oh Yeah’, which have a lot of edits this was important. You can hear these edits. They are sometimes very brutal but Jaki had the last word on it if the groove didn’t work.

‘Midnight Men’

Irmin Schmidt: Upstairs in the castle there was a whole family living there the whole time we were there. A sculptor with his wife and five year old daughter. They were about our age. This sculptor was Ulrich Rückriem who now is one of the most famous sculptors in the world. He has built huge monuments all over the planet. In New York, Toronto, Canada, Tokyo… he makes very big rocks with one side polished and one side raw. Very subtle, very minimal, very beautiful. So he was living upstairs from us and our constant use of the hallway and all the noise was quite uncomfortable for them. And we played at night. So they couldn’t sleep. After a year or so we had to move out because poor Ulrich and his family couldn’t sleep. Then we found a huge cinema to practice in which was in another village near Cologne. We had to rebuild it for our needs by putting mattresses against the walls and all that. So we made our studio there in Weilerswist at the end of 1971 until the end.

Holger Czukay: [laughing] Are we taken seriously by the art establishment in Germany now? If this has happened it was not something we were expecting. It was not something we were counting on.

‘Networks Of Foam’

Irmin Schmidt: Some of this material could have been released back in the day but at the time you just released one record per year. So when we started we released Monster Movie and still we had a lot of other pieces hanging round. Monster Movie was an album chosen from a potential 20 recordings. Then when we made Tago Mago we had recorded a lot more pieces and had to choose from then. So you know you don’t put everything out or you would be putting a record out every three months. Also, when it comes time to release an album your style may have changed, you may have progressed and you don’t want to put the old stuff on a new record so you put it in the archive and then it gets forgotten about. At the end of the day we’re quite happy to have found this wonderful old stuff. That’s nice isn’t it?

‘Messer, Scissors, Fork and Light’

Irmin Schmidt: It is very, very true this idea that Can songs are never finished. We even wrote a song called ‘Unfinished’. You can stop the process at a certain moment but it could go on in theory. In all of our work this idea is resonant. In this case the song ‘Spoon’ first came at the same time as the opportunity to make the theme music for Das Messer – a German cop show, which also came along at the same time as the suite, ‘Messer, Scissors, Fork and Light’. In this case, this is the actual music that’s in the TV show, the elements of which in the end we made the title song from. So the title song and the TV music were parallel with each other and it was one process to make it. Elements occurred and slowly the song was gutted to make the final version while at the same time pieces of it became the incidental music. The incidental music disappeared in the archive.

‘Barnacles’

Irmin Schmidt: A lot of the time in the mid-70s we felt quite funky.

Holger Czukay: We didn’t jam. We were not jamming in Can. We were not even improvising. We were instant composing. ‘Barnacles’ is an example of this but not so symptomatic of that many other Can tracks even if they were all essentially starting in exactly the same way. With each separate track it always depended on the mood we were in.

‘EFS 108’

Holger Czukay: ‘EFS no. 108’ was one of our Ethnological Forgery Series. Can was only interested in music that people were currently doing and this was exotic for us, it was completely new. When the project first started we pretty much only listened to European music but then we began to imitate this ethnological way of singing. Irmin was doing a Japanese voice singer. Especially from my point of view I had started this musical access which was really combining this international music with the European music.

‘Private Nocturnal’

Irmin Schmidt: We never said, let’s play like this or that. We just started to play then an idea came up during improvisation and then we really started to concentrate to get the nucleus, the groove of an idea, by listening really carefully to each other and playing it again and again and again so we could get nearer to the essence of the idea. And it was always a strange subtle balance between spontaneity and highly disciplined concentration.

‘Alice’

Irmin Schmidt: One evening Wim Wenders called, asking if we could make a film score overnight. He thought his film Alice In The Cities wouldn’t need music, but his editor Peter Przygodda convinced him otherwise: music was needed and it had to be by Can. Three hours later he was there and made it the next morning on time to the mixing studio, with the music.

‘Mushroom’ (live)

Holger Czukay: Damo was always constantly good. It would be hard to say which was his best performance but my favourites include ‘A Swan Is Born’ and ‘On The Way To Mother Sky’ but most of all, ‘Mushroom (live)’.

Irmin Schmidt: You cannot avoid bootlegs. There are pieces that are on this that have been released on many bootlegs before now, but the quality of this is much better because they are mastered much better from the original tape. There was some guy in Israel who collects Can bootlegs who collects them from all over the planet and he offered us over 200 of these things but I’m not really interested in that. You can’t fight them so just relax and forget about it!

‘One More Saturday Night’ (live)

Holger Czukay: Personally I hadn’t forgotten any of these pieces of music as I started carrying out research into my own version of these albums about 20 years ago. My idea for this was to make completely new versions. My idea was completely different versions. I didn’t want to just take stuff out of the archive and present it, I wanted that everyone remaining in Can was to get creative and represent them for the modern day.

Jaki Liebezeit: I think Can’s music doesn’t have any style…I think Can had no real style, you cannot classify it to say it’s rock or funk. People were discussing it then asking, ‘Is it rock or is it not rock?’ But I don’t care actually. It’s not real rock because it doesn’t come from blues.

Next month John Doran visits Cologne, Dusseldorf, Hamburg, Berlin and Dessau for a state of the scene report on German techno