As part of the Kinoteka Polish Film Festival, currently happening at various venues across the UK this month, Andy Votel is presenting the final event, Kleksploitation this Sunday at the Barbican Centre Cinema 1. Kleksploitation was originally commissioned by Unsound festival in Krakow and features Votel, film editor Andy Rushton and esteemed Polish film composer and left field musician Andrzej Korzynski collaborating to produce "reconstituted cinematic synth-pop from Communist Poland’s deepest hallucinogenic hibernation period". In the last decade of Communist Poland, Korzynski composed music for a series of three surreal sci-fi films for children called Pan Kleps – music which Votel describes as being some of the freest, most self-contained music to come out of Poland. Using the film and soundtrack as raw material they have made a cinematic and musical edit which promises to be an astounding and stimulating experience.

I went to Poland with art school in 1994 and discovered their music out of a want for any music at all really. Someone told me there were good jazz records in Poland, but I guess I was expecting US jazz records, not what I discovered. I ended up buying a load of LPs because of the sleeve art, which is how I’ve ended up with this bloody ‘penchant’ for buying Eastern European records ever since. Out of all the Polish records I bought, Andrzej Korzynski’s name seemed to be on most of them. Some of them were good, some of them were bad. Most notably I’d see his name on records by the synth band Arp Life and one of the only compilations of his film music to come out of Poland during the Communist era, so I knew of him. Then three years ago I started working with this guy called Dan Bird on a German documentary about this [Czech New Wave] film Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders. At the time he was also working on extras for a DVD of Possession by Andrzej Zulawski. When I was at his house he played me this kind of Amon Duul style music to a film called The Devil, and I was like, "This is fucking insane." But, typical of any state owned film industry, the soundtrack had never come out. In Communist countries film soundtracks very rarely came out. He told me it was Korzynski and I knew him from the Arp Life records I used to buy in Poland. He asked Zulawski for his number, I called him, he told me his story and we became friends. But Korzynski’s story is mental.

He was a radio producer and jazz musician for a Polish radio station. He worked on the censorship board, dealing with what American music could come into Poland. So he had an inside track on foreign sounds, and this led to him writing these quite anthemic Polish pop tunes. When he was a kid he was friends with Zulawski. When Zulawski went to study in France to work on a couple of badly edited French films, he brought Korzynski as a young dude over to Paris in the mid-60s. He went to France and worked in the same studios as Jean Claude Vannier and Francois de Roubaix. He was only there for a few weeks, but he was a contemporary of people like Vannier.

And then in this few weeks out of Poland he got an offer to go and work in Italy, and he met Ennio Morricone, and it was like stuff was really going to blow up for him. He went home to Poland to get his shit together so he could work with these people, and they just arrested him and took his passport. So, Communism shattered his dreams really. They had his passport for five years, but during that time the riots in Prague and Paris happened. He missed that whole art house thing that happened. He carried on working for Zulawski, but one after another his films were banned by the Polish government. And this was the golden age for Eastern European cinema. It was the time when people like Polanski were coming over to England and to America. He missed this golden era because he’d had his documents taken off him.

There were a lot of very forward looking films made under Communism, and likewise Korzynski was certainly avant garde in the 60s and 70s, because he had those chances to go to Paris and Italy so he was at the vanguard. And because he was working on vocal music, he was being quite subversive. The only comparison really from around this time was Polanski’s right hand man [for music] Krzysztof Komeda, but he was doing straight ahead jazz. Because Polanski was such hot property as an export, you tend to hear about Komeda more.

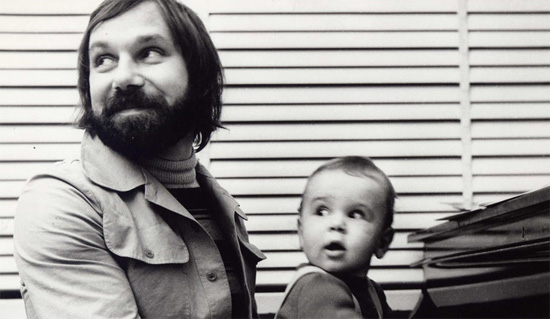

Andy Votel

I don’t know what it was about Communist countries and funk. I think people had really, really good imaginations and would revert to these primal live rhythms, and especially in Hungary everything was super sex driven, everything was doused in sex. But in Poland the sound was really raw. If they heard a microshard of fuzz guitar coming from the West on East German radio then they’d cover everything in fuzz guitar. They had punk down in Poland. It was all leading up to a more blues orientated punk sound, up until the wall coming down. What you’ve kind of got across all the countries is a perverted approximation of what’s really going on over the other side of Europe. And by today’s standards that’s what you kind of crave for in music. Say for example when I’d buy all these records I’d be like, ‘Wow, the drums are really loud.’ I’ve dreamed of English or American records where someone would just turn the drums up because in the 80s that’s what I wanted. But in Communist countries it was like the rule book didn’t exist. They seemed to pervert things by mistake and that’s what you want – especially when it comes to rhythmical music. That’s what you need.

So up until the mid-70s he was just toeing the line. And then from the mid 70s through the 80s is the time we don’t really know about in Poland, and that’s when he was making this crazy kids’ music, and because he had to be absolutely apolitical he had to resort to making this completely abstract music. It was surreal, what he was making, almost silly in a way, this music that sounded like it had come from an alien world, and it’s even weirder because it was never meant for export. That’s why free jazz was so prevalent in Poland, because you couldn’t really say it had a message. So we’ve done these compilations on Finders Keepers of all this French new wave sounding, Morricone sounding stuff from the 60s and 70s – but when he gets to the 80s, well, that’s when we get to the music we were never meant to hear. It’s all from a really weird time when Poland simply wasn’t communicating with the outside world. Communism was a beautifully double edged sword for him at this point.

But it was weird what Communism did to the film world in the 70s. The authorities would happily spend money on equipment rather than people. The TV companies would buy the most expensive synthesisers. This was a Communist thing. There are stories of Hungarian prog bands who went to tour in the UK or Japan and they weren’t allowed to be paid in money, so they would be paid in synths. So Korzynski had these amazing synthesisers, even though he was earning the same wages as everyone else. It was the same with the Czech New Wave. They’d give these directors these fantastic things, even though they knew these films, like Daisies, would get banned. But they made so much on export to the West that it didn’t matter. As long as none of the people involved became superstars, it didn’t matter. And this is why Korzynski started Arp Life. That was his first Eastern European synth orchestra. And in the 80s he had 303s and 808s. They were the freshest instruments – that’s why they had them, they didn’t have any concept of acid house or electro or disco, and they didn’t need to have any concept of them either. The way he explains it to me now is they’d only get the merest morsels of what was going on in the West, and they certainly wouldn’t hear anything like acid house.

But you can end up with a sound that is somehow comparable, just because he was using the same equipment. The example that always sticks in my head is that of Charanjit Singh. I translated a German version of Pan Kleks and someone had said that Korzynski was like the father of acid house, and bits of the music do sound like this super 303 acid, but it’s just this mad kids’ pantomime stuff. And if Korzynski is father of acid house then acid house is also like his bastard love child, because neither Korzynski nor acid house have ever met each other up until this point.

Film trailer for Kleksploitation

Secret Enigma was the first material of Korzynski’s that we released on Finders Keepers. Polish pop and psych has got a definite raw sound to it – Hungarian music would be more of a smooth funk sound and Czech stuff would be more cinematic – but I’d never heard any Polish music that sounded that much like French or Italian music, so I was amazed when I first heard this stuff. Most of the stuff on Secrect Enigma never made it to vinyl. They were genuinely lost tapes. So we had the stuff that sounded like Vannier, the stuff that sounded like Morricone, the stuff with all the synths, and then when he starts using 303s you’re thinking, "Jesus, this guy is ticking every box." But unlike Morricone, no one has heard of this guy… Secret Enigma was the perfect name for the compilation.

When he made Pan Kleks it was like for Christmas TV, and by that stage it wasn’t difficult for him to make music, but his audience was a totally apolitical children’s audience. So you had this forward looking guy with loads of talent, who had the best equipment in the world, he’d been to France and Italy to meet really talented musicians but was making music for kids, so it was like the most uncontrived music with [the highest] artistic value. It had political restrictions on it, but within that it became anti-fashion in a way, and by Western standards it became freer than space jazz. To be restricted as a musician or painter by politics, that’s one thing, but without having any regard to fashion or the West, and just be a musician. It was probably freer in some respects.

If you take the film Daisies, by [Czech film maker] Vera Chytilová. It has these amazing prismatic filters and recollaging and reprojecting and it looks like a Stan Brakhage film. They were just like each other. The state controlled stuff in Czech, they had the best studios in the world. Just for export mind. But if you gave them a project you could do it. They had these super synthesizers in the TV studios. But if you were Stan Brakhage or a French synth pop you had to save up for these instruments. There was no way you were going to be able to compete if you were from the West – it was really important for the East to make out they were more advanced, especially when it came to things like sci fi. So it was a total double edged sword. But Korzynski just worked on TV from that point. So I guess it was a special way of communicating that he came up with.

So he gets to the stage in the 80s where he’s basically making kids’ TV programmes. Pan Kleks is a series of three films which is like a pantomime basically, but concerning sci-fi and magicians essentially. It’s crazy Christmas kids TV, there are people rapping on it, people breakdancing, driving spaceships and missiles, there are people blacked up in it, in Chinese eye make-up, there are belly dancers in tin foil suits. Breakdancers driving the best space ships and missile launchers ever dreamed of, just so the show’s producers could prove they were better than the West. So when you get the soundtrack for this crazy shit – if you want to review it or dissect it you have to come from this Communist’s headspace to get it… to get how anti-fashion and truly abstract it was.

Kleksploitation

What I’m trying to do now is to recontextualise it and dissect it. Regardless of the language it’s untranslatable, it’s the most alien concept… but with ingredients that are familiar, like 303s and 808s. So it could be Korzynski’s best work, but as the product of concentrated communism it’s like pop culture gone mad. And if anything I’ve exploited it even more than it ever was.

As well as Secret Enigma, the compilation, we’ve issued the soundtrack to Possession by Andrzej Zulawski. When you get something like Pan Kleks it’s perverted in one way, and then the soundtrack to Possession is perverted at the other end of the scale. Before Possession, Zulawski’s three previous films had been banned. It’s a weird story with him. The first two were quite blatant political allegories and were banned because of that, and then his third was banned for political and budgetary reasons. So then New York bailed him out. He followed Polanski and [Jerzy] Skolimowski over to America. Then he wrote a script about "a woman who fucks an octopus" and then, when that came out in the West, that was banned as well! They [BBFC] didn’t understand it and lumped it in with all the video nasty stuff. It was like he came over to the West to get freedom and then got banned over here, but for the most immature of reasons. Korzynski-wise, they were estranged at this point. So you’ve got Zulawski, the guy who travelled the world, and he was looking back at Berlin, where Possession is based, in a very depressive manner, and Korzynski is looking at the city like the gates of freedom. So you’ve got this conflict going on in this record. And he was using the same stylistic approximations that were going on in his head to make horror music that he was using to make kids’ sci-fi music. They’re almost like yin and yang.

The next soundtrack we have coming out of his is Man Of Marble, which was an Andrzej Wajda film, and it was notable because it was one of the only film soundtracks he did with Arp Life, his synth orchestra. There were three core members of the group and that would be widened to ten members, so at any given time there are up to five synths playing. I really liken Arp Life to when Goblin started doing disco stuff later on in the 70s. There was a synth band in Russia called Zodiac, but other than that there were very few people who bridged that gap between soundtrack work and live disco gigs. There was a prog group called Omega [from Hungary] who toured the UK a few times, and because they couldn’t get paid in money, they used to get paid in synths. Then, when they had all the synths they needed, they started to get paid in bits of lighting rig. That band now organize stadium events as a production company because they inherited so much technical gear. It’s all because they were massive but they weren’t allowed to be massive. There was another band, Scorpio, who went to Japan and got paid in Suzuki bikes.

What I’m doing this weekend with this Kleksploitation event is what you’d call an edit. In one way it’s no different from a DJ mix, but then you’ve also got your new age Vangelis style sections in there, then synth pop, Polish post-punk and Middle Eastern section. Because basically this kids’ TV show just provides a palette of amazing synth sounds basically. And we’ve done the same with the film as well. The film is Banana Splits meets Os Mutantes, but in a more nostalgic and cross cultural way. It’s also in a way quite authentic to my own childhood, remembering films such as Picture Box, Tales Of Europe and those European animations that they’d literally butcher and reassemble – like the Little Mermaid and The Singing Ringing Tree and loads of Eastern European animations – which were reassembled to appeal to this perceived, general childish logic. I think our generation has these confused memories of Eastern Europe through 80s TV that we probably weren’t even aware of.

A week after publication we received an email from the publicity department of the BBFC containing the following statment: "The BBFC actually passed the film X uncut for cinema release in 1981. This meant that the film could be viewed in UK cinemas by persons over the age of 18. Although it’s true the film was subsequently added to the Director of Public Prosecutions’ list of potentially obscene videos (video nasties’ list), the BBFC played no part in the creation of that list. When it was finally submitted for classification on video it was passed 18 uncut." Ed