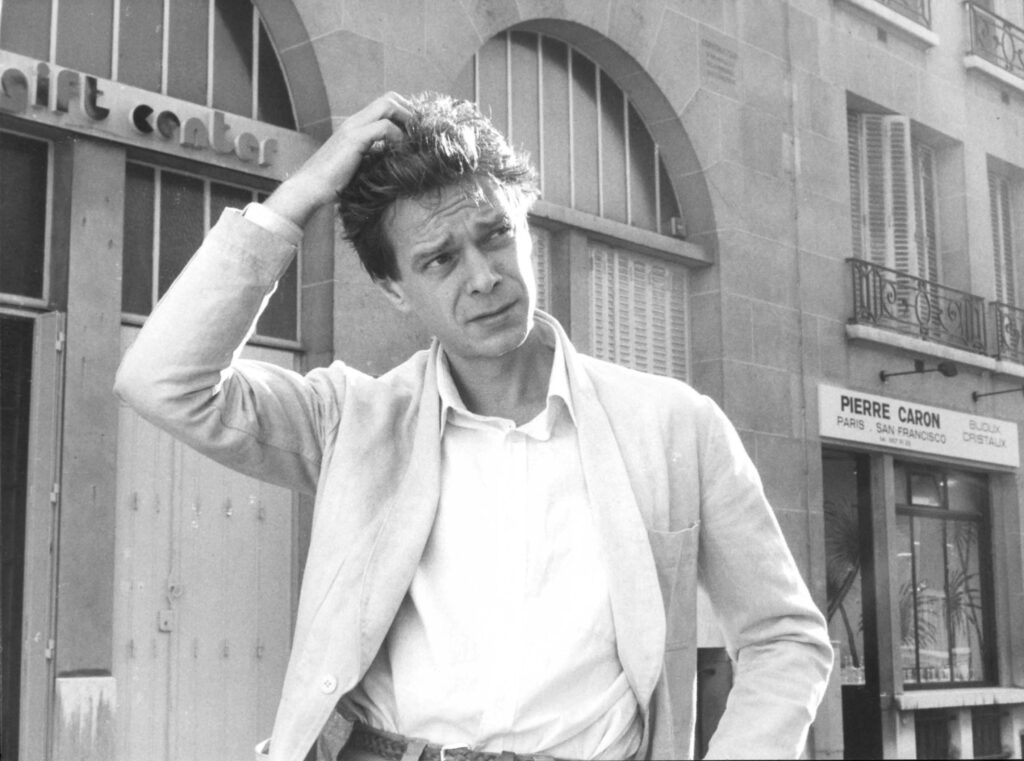

Below, Jean-Claude Vannier recounts how the writer Michel Houellebecq once said to him, “Every time I hear a song that I like, you’re always involved in one way or another.” At the end of last year when I was listening to Emmanuelle Parrenin’s Maison Rose for the first time, I was quickly struck by ‘Plume Blanche, Plume Noir’, with its sinuous melody line and elegant rhyming scheme… if you spend any amount of time digging into French pop from the 60s onwards, often you’ll be stopped in your tracks by an arrangement or a particular chord progression and you’ll think “I bet Jean-Claude Vannier’s involved in one way or another.”

He’s best known as the arranger and co-writer of Serge Gainsbourg’s much-discussed and dissected (literally, in the case of those who, like David Holmes and Portishead, have sampled it) Histoire de Melody Nelson and, thanks to Andy Votel’s Finders Keepers reissue imprint (on which it was the first release), for 1972’s L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches, an album that pushed the progressive orchestral rock sound of Melody Nelson even further, favouring a more aggressive, even nightmarish energy over the former’s comparatively sedate psychedelia. Those twin conceptual peaks aside, though, he’s had a hand and more in records by some of the key figures in French popular music, including Barbara, Françoise Hardy, Michel Polnareff, Juliette Gréco and Brigitte Fontaine (the list could go on), as well as revered film soundtracks like La Horse and Slogan.

I first spoke to Jean-Claude Vannier in 1996, the morning after an intimate show in Kilburn where he’d shared the bill with Sébastien Tellier. Discussing the sound of Fontaine’s magical debut, Brigitte Fontaine Est… (also sometimes called Brigitte Fontaine Est Folle or Brigitte Fontaine Is Mad) he described it in a way that translated as ‘tin-can’ or ‘tin-pot’ music. That’s certainly one way of evoking the carnivalesque colours and vivid punctuation that define a Vannier arrangement but it doesn’t do justice to the unsettled (and unsettling) dynamics of his own compositions, where a moment of reflection or stately melancholy can be undone by a queasy change in key and/or chord, like your stomach turning over in nervous anticipation or as a panicky realisation sets in.

As well as applying his considerable skills to collaborations with others, Vannier has, from L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches onwards, released numerous records under his own name. The most recent was a double featuring a live performance (En Public) and a selection of home recordings (Fait Maison). Now, thanks to Andy Votel again, we’ve got another pair of releases – an album of new songs, Roses Rouge Sang, recorded with many of the original musicians from Melody Nelson and L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches (session veterans like bassist Herbie Flowers and guitarist Vick Flick) in London and Paris and the String Radio Orchestra in Sofia, and Electro-Rapide, a compilation of rare and unreleased instrumentals.

The latter is not very electro but it’s definitely rapide, an appetising 25-minute zip through themes and jingles that take in afro-percussion, soft-psych, surrealistically jaunty dance numbers and even a ‘ballet for midwives’. Roses Rouge Sang, meanwhile, sees Vannier taking on vocal duties as well as leading the experienced musicians through some typically rangy compositions. Even with the strings, it has a close, dry room sound (the drums get the most reverb) – on ‘La Vie En Live’, one of the elements of the arrangement is crackle made by messing around with a guitar jack – while Vannier muses on, amongst other things, the roses in his garden and Scrabble.

At one point in the interview, I detect irritation at the suggestion that, given the personnel on board, Roses Rouge Sang might hark back in some way to Melody Nelson. That’s understandable – I don’t think it does for the most part, its sound particularly is something new for Vannier I think – but of course certain stylistic traits persist throughout his work. Which is absolutely fine, the same has always gone for Burt Bacharach, for example, whom Vannier admires. To say to yourself about a song “I bet Jean-Claude Vannier is involved in one way or another” is also to add “because he’s inimitable, because it couldn’t be anyone else.” (NB Beck copping the Melody Nelson sound wholesale on ‘Paper Tiger’ doesn’t count!).

When we spoke in 2006, you hadn’t yet played the show at the Barbican where you performed Histoire de Melody Nelson and L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches together. How was the experience?

Jean-Claude Vannier: It was pretty extraordinary, to be honest. It was most unexpected and I was particularly surprised by how successful it was. Andy (Votel) had asked me originally if I wanted to do it with just ten musicians, and obviously it wasn’t going to be possible like that but then he said it would be possible with the BBC (Concert Orchestra) and that there were 50 choristers and so on, and thanks to that I was really able to bring L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches and Melody Nelson back to life. Since then I’ve done it in the US and in Paris, and it’s thanks to Andy and the Barbican.

There seems to be a certain generosity in the way in which you and, for example, Jane Birkin continue to share the music that you made with Serge Gainsbourg. Do you think that’s particular to people who worked with him?

J-CV: In Jane Birkin’s case, obviously, her music career wouldn’t have existed if it wasn’t for Serge. In my case it’s somewhat different as I wrote most of the music on Melody Nelson. As it happens, we’re going to put out an unreleased track on the version of the album that’s coming out in November called ‘Melody Lit Babar’, it’s a piece we set aside because we thought at the time, and I still do, that it was a bit too much for ‘Melody Nelson’ but, anyway, the label has decided to release it. But in terms of why I play Melody Nelson so much it’s not as a tribute to Serge, it’s because I wrote the music and some of the words. The fact that people like Jarvis Cocker and Beck come to the music because they’re fans of Serge is great, and the fact is that it’s music that hasn’t dated, it has survived its era.

You’re very attached to the idea that songs are ephemeral, that they belong to a particular moment, so is it strange to find that the music from these albums has had this kind of longevity?

J-CV: I think songs are a reflection on what’s happening currently, or a form of nostalgia. What I think, though, is that we knew we had something fantastic, lots of amazing songs, and that something went wrong, there was some kind of mishap, I don’t know why… it had everything it needed to be a success but it didn’t happen. So often I tell myself that anything is possible but you’re never entitled to anything. A song always contains a kind of regret but in the end saying that a ‘song’ is a particular thing, I don’t know, because there are a thousand ways to write a song and I don’t think there are necessarily rules, you see. I write songs for women, or men who are somewhat feminine, or friends, and the seed of the song is usually a regret… I released a song at the beginning of this year with (Michel) Houellebecq for example, and there’s always this desolate but also humorous feeling, a kind of amused response to a general climate of catastrophe.

Can you tell me about working with Houellebecq? Do you share his worldview, or the one that comes across in his books in any case?

J-CV: I think he’s extraordinary. I met him before he was famous, when I was awarded Le Prix de l’Humour Noir (an award for services to black humour), and he came to see me and said “I would like to introduce myself, I’m Michel Houllebecq, I’m a poet” – at that point he’d written several books of poetry – and he said “It feels like every time I hear music or a song that I like, you’re involved in them in one way or another, and I wanted to meet you.” I was very flattered, and so he came to my place in the country. He wanted us to work on some songs. I wanted him to actually sing them – and you know, he’s not a great singer, he’s not an opera singer, he’s rather like me – so I got him to have some singing lessons and we recorded these two songs together. I like it a lot, I was very pleased with the record.

Michel Houellebecq – “Le film du dimanche” by ubulettersOne thing that occurred to me listening to Roses Rouge Sang is how well the subject matter of your songs, which is usually related to the erratic stirrings of the heart in some way, sits with the unpredictable nature of your chord progressions.

J-CV: Unpredictable is exactly the right word. When I was young my father listened to Vivaldi all the time and it annoyed me because he was always able to find the next phrase, you know the violin would play something and he would whistle what came next because it was clearly very predictable. I try to not be predictable. The great song composers, like George Gershwin, Burt Bacharach and Cole Porter, if you listen to their songs there are always surprises, do you know what I mean? I try, in my own way because I’m not going to compare myself to them, to create surprises.

And that goes very well with the emotions you’re describing.

J-CV: Completely – with a song, the music is not enough in itself and neither are the words. You need both together and I try to make it so that the melody suggests the same emotion… sometimes when you hear a song that’s in a language you don’t understand, you still understand what the song is about.

You’re not often spoken about as a lyricist, always as a composer/arranger…

J-CV: It’s true but I’ve always written the words to my songs.

You’ve said in the past that you sing things that other people aren’t capable of singing?

J-CV: Yes because the subjects are things which, in France at least, other people don’t want to sing about, like transvestites, homosexuality and drugs, and there aren’t many singers, especially male singers, who want to sing about that kind of thing. I’m my own guinea pig if you like, I test these things out on myself. As you have noticed, the melodies and the harmonies aren’t particularly standard either, and a lot of singers prefer more everyday, more commercial things.

I know you have a passion for cabaret, watching singers in clubs around Europe. Are you still able to travel and watch these kinds of performances?

J-CV: Yes, I love that – people singing Fado, or in Naples, I’ve seen people singing in Neapolitan, I love that, it’s magnificent.

Do you think your songs are in that spirit?

J-CV: Yes, i’m highly influenced by all the things I listen to, I love gypsy music, the blues, tango, klezmer and music from Eastern Europe so I’m sure there are elements from there that come out in my music.

I recall you saying that you don’t like it when music is played in public places like restaurants…

J-CV: No, I absolutely hate it when music is played in shops and particularly restaurants, when you’re there to talk, to discuss things, and you’ve got this music tugging at your ears, it’s intolerable. When I’m talking to someone and I can hear music in the background, even faintly, I can make out all the notes, and it takes over my attention to the point where I don’t hear what people are saying to me any more. So now I avoid restaurants where they don’t play any music, or if I do go to one I ask them to turn it off. But I love hearing music in a theatre.

The last thing I heard from you before Roses Sang Rouge was Fait Maison, which was an album of home experiments, where you recorded the sound of dripping water on one song for example, and with Roses Rouge Sang you’ve gone completely the other way, musicians playing together in a room…

J-CV: Yes, Fait Maison was an experiment I carried out by myself with some instruments, and it was deliberately small-scale, quite restricted and created with limited means, which is a situation that I find can sometimes be a stepping stone for the imagination, having constraints. But with this record my friend Bruno Coulais, who is a producer and film music composer in France, said “We’re going to make a record and I’ll pay for an orchestra” so we did that. I like going from one to the other, of having 150 musicians on stage at the Barbican, then doing some shows by myself with my guitar and a piano.

Apparently it was during rehearsals for the Barbican show, with some of the original musicians who played on Melody Nelson and L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches, that the idea came to work with them again.

J-CV: Yes, I took advantage of having them there to do some things with them.

Had you remained it contact or worked with any of them since those sessions or had it been a long time?

J-CV: Some of the English musicians I hadn’t seen for a long time, and it was the same for some of the French ones.

Did you rediscover the atmosphere of the records you made with Serge?

J-C: No, I wasn’t looking to recreate the atmosphere of the records we made back then. It wasn’t anything to do with nostalgia, I really don’t care at all about that, and I never listen back to things I’ve done in the past. It might remind you of things I’ve done before, perhaps I always do the same thing, I don’t know.

Not really, certainly not in terms of the sound. I think a Jean-Claude Vannier song always has something that is distinctively, recognisably yours. Maybe the stripped down bass and drums of ‘Les Yeux Valises’ recall Melody Nelson but that’s about it.

J-CV: Yes, well it’s the way I write.

So the album was recorded in Paris, London and Sofia. Were the band(s) all recorded together?

J-CV: The group was always together – bass, guitar, me on the piano and the drums, with Doug Wright (drums), Vic Flick (guitar) and Herbie Flowers (bass), and in Paris with the French musicians it was the same group set-up – sometimes we used the recordings from the UK – and we recorded the strings in Sofia.

How much freedom do you give your musicians?

J-CV: In general I direct everything very precisely, they’re not improvisations but I don’t want everything to be completely planned. So I write as much of it as possible, it’s not like a jam session or a rehearsal but when we’re there if a musician has a more interesting suggestion then we’ll use that. What I don’t like is improvisation, because often I find that when musicians improvise during sessions, they’ll do something they’ve already done a few days earlier with another band leader.

The release of Roses Rouge Sang is accompanied by Electro-Rapide, a collection of rarities…

J-CV: I’m not really sure how that’s ended up, Andy loves it but for myself I don’t really have an opinion on it – as I said, I rarely look back and I don’t have much of an idea about what it is.

So they’re not pieces you hand-picked yourself?

J-CV: Yes we chose them together, also because there were some things which weren’t worth much really that we didn’t include.

Was it an uncomfortable process for you?

J-CV: No, not at all. It’s great working with Andy, he’s someone extraordinary, I trust him completely. It was Andy who had the idea of reissuing L’Enfant Assassin des Mouches, I had no idea of whether it was worth reissuing or not but I’ve come to realise that plenty of people like it.

Do you have an idea of what you’ll be working on next?

J-CV: I don’t know, I’ll see what happens with this record, how it’s received. There will be concerts from January I think, not necessarily with the same musicians. But I do like Herbie Flowers a lot and if I have the opportunity of working with him again I’d like to.

Do you mind whether the reviews are good or not, is it important for you?

J-CV: It’s not important for me because I’m used to people saying anything and everything about me – and I always feel as though they’re talking about someone else – but it’s true that the producer and the distributor need the record to be talked about, and it’s important that I have the confidence of Andy and Bruno so that I can make another record, that’s what interests me. I’ve never wanted to be famous, it doesn’t interest me at all. All the famous people I know are insane.

If the label needs a record to be successful and to be talked about, what do you need ultimately?

J-CV: Making the record is important, and it’s important that I’m loved. I don’t want to be admired, I absolutely don’t care about admiration, I want to be loved.

What’s the difference for you?

J-CV: Well, behind admiration there’s hatred, but behind love there are possible futures.

For more from Rockfort, you can visit the official site here and follow them on Twitter here. To get in touch with them, email info@rockfort.info.

Roses Rouges Sang and Electro Rapide are both out now on Finders Keepers