At the heart of every slasher movie there’s a chilling protagonist – a Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers or a Chucky – practically unstoppable, coldly methodical and able to put up with seemingly endless amounts of punishment before their reign of terror comes to an end. As luck would have it, Video Nasties: Draconian Days, Jake West’s documentary on the restrictive censorship of films in the UK following the implementation of 1984’s Video Recordings Act, features one as well, in the shape of the then head of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), James Ferman. Ferman is a fascinating character and the documentary does a solid job of revealing the hows and whys of this former director of TV drama and his borderline hysterical campaign against the type of horror movies that will now forever be called ‘Video Nasties’.

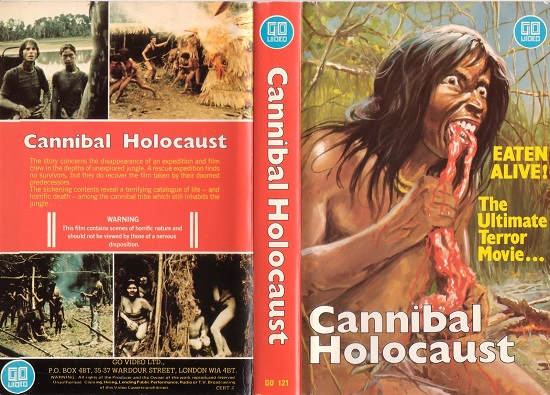

Readers of a certain age may well have some fond memories of the types of films referred to here. What trip to the video shop in the 80s and early 90s was complete without a surreptitious peek at the cover of Lamberto Bava’s Demons? Or the terrifying jacket art to Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead? These clunky, gorily packaged items were constant sources of fascination. (Although I believe I thought it quite likely that if I watched any of them I would actually die of fright.) West understands the appeal of the films perfectly and his documentary is crammed with examples of artwork and short intriguing clips, often tantalisingly obscured behind crackling clouds of VCR distortion.

That the film is a labour of love is obvious, and it’s unfortunate that that can’t save it from being yet another talking heads doc. However, the story being told concerns such an interesting period in British cultural history that West should be commended for letting it unfold with the minimum of fuss. Through interviews with film directors, critics and Ferman’s BBFC colleagues a portrait is built up of complex and contradictory man. A man not averse to destroying whole reels of film, fudging the minutes from official meetings and finally – and fatally for his career – going completely over the heads of his colleagues and the government with one of the most audacious liberalising policies ever attempted in this country, which saw hardcore pornography freely available for sale in specialist UK shops for the first time.

Indeed, it’s this act which provides the key to Ferman’s character. Despite his reputation as an enemy of free expression, he often came down on the other side of the censorship debate. For example, he strongly opposed politician David Alton’s ludicrous amendment to the Criminal Justice Bill, which sprang up in the outcry following the murder of James Bulger and it’s alleged connection to Childs Play 3, and which would have effectively banned any film rated higher than a PG (a climate of paranoia evoked by the film using hysterical chat show footage and frankly hilarious scenes of an unassuming horror nerd’s house being raided for contraband video cassettes). But it’s moves such as these which make his complete resistance to overturning the ban on films like The Exorcist seem even more bizarre – the actions of a man on a lone moral crusade, impervious to all advice.

But no matter how much his background in the arts and legalising of hardcore grumble indicate his levels of grooviness, Ferman’s chief flaw was being obliviously posh. His widely quoted remark concerning the alleged effect of Texas Chainsaw Massacre on a hypothetical builder from Manchester is justifiably infamous, but it’s during an interview included in the film, when talking about people’s reactions to portrayals of rape, that Ferman comes out with a quote that absolutely nails him in temperament and time. He worries, he says: “that people can watch them over and over again in the privacy of their bedsitting rooms and freak out on them”. “Bedsitting rooms”, “freak out”, the kind of statement that’s more likely to come from an out of touch public school humanities teacher than a self-righteous moralist.

With such an interesting character at its core the film is never less than compelling, but when it goes into detail on the underground movement that kept these film’s reputations alive it becomes fascinating. A country wide network of fanzines, illegal tape trading and VHS fairs kept films like Invasion of the Blood Farmers, Shogun Assassin and New York Ripper in the public eye, with that level of fandom leading to the formation of companies such as Arrow Video and Death Waltz Records and their lovingly crafted reissues and pressings of horror obscurities from around the world. These fanatics are basic proof that the more you attempt to tell people what films they can’t watch, the more you coat those films with a patina of gruesome glamour, one that still hasn’t faded away. As one of Ferman’s colleagues says about New York Ripper “The dispiriting thing is not that it was made… but that there’s an audience for it.” That’s something all gorehounds should be extremely grateful for.

Video Nasties: Draconian Days is showing at London’s Prince Charles Cinema on Thursday the 3rd of July, followed by a Q&A with numerous special guests. Details are here: http://www.princecharlescinema.com/events/events.php?seasonanchor=videonasties