Life isn’t fair, so it stands to reason that neither is the world of film. For every critically acclaimed, gong-grabbing mega-hit parading its pearly whites up the red carpet of success there are a whole slew of cinematic buck-toothed stepchildren trapped in the basement of ignominy. Many of them deserve to never see daylight again, but amongst this unhappy breed lurk more than a few great films that have never received their just desserts. Whether this is due to bad luck, poor timing, the ignorance of the public or some combination of all three, these are films that have been misunderstood and shunned by the world at large.

One of the great things about fandom, and something that stretches across all mediums, is that we all like to argue until we’re blue in the face about the merits of those favourite works of art that no one apart from us really understands. I have pounded pub tables into match sticks arguing that Ralph Bakshi’s head-spinningly psychedelic Lord Of The Rings is a visionary masterpiece, that Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives will one day be acclaimed as the work of sad genius that it is, that Disney’s Robin Hood is a kind of children’s adventure version of Two Lane Blacktop. Talking about these and the many other works of art that never received their due is a joy, and certainly more fun than yammering on about films that everybody agrees on. Why would you want to blather about Alien for the thousandth time when the person sitting across from you has never seen Galaxy Of Terror? Sure Godard’s Breathless is a redefining masterpiece, but is it really better than Jim McBride’s 1983 remake? I like Audition as much as the next guy, but put it next to the same director’s Ichi The Killer and I know which one I’m going to go for.

Of course, many of these arguments aren’t exactly what you’d call reasonable – I’m still pretty confused about my position on Robin Hood, to be honest – but they’re compelling because they arise from pure passion. Our reasons for favouring one work of art over another don’t have much to do with rationality as much as they do a combination of circumstance, gut feeling and pure bloodymindedness and it’s in this spirit that the Quietus film team have chosen their favourite underrated and misunderstood masterpieces.

Of course this isn’t a definitive list, and feel free to have your say, but rather think on the films written about below as jumping off points for discussion, good natured debate and the joyous hammering of pub tables.

Mat Colegate

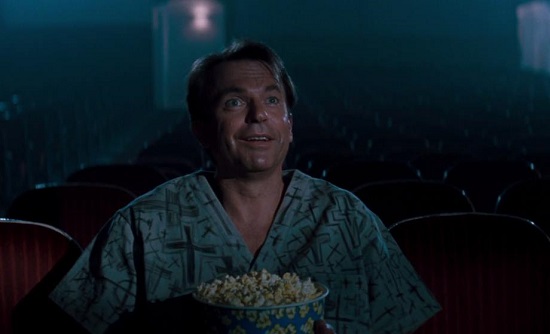

In The Mouth Of Madness (John Carpenter, 1994)

John Carpenter’s In The Mouth Of Madness was released in 1995, a strange time for horror cinema. The tide of cannily ironic teen flicks, ushered into being by Scream, was yet to come. The slasher excesses of the ’70s and ’80s were now embarrassing franchise fodder. The closest horror got to dominating the box office was via films like Interview With The Vampire, Wolf, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula – literary, serious and interminably dull. From the opening sequence – hard rock soundtrack, lurid blue text over images of a printing press churning out pulp horror paperbacks – In The Mouth Of Madness nails its brash, unapologetic colours to the mast.

Sam Neill, in yuppie-lite mode, plays John Trent, an insurance investigator employed to track down Sutter Cane, a horror writer whose work we’re told outsells (and outscares) Stephen King’s. Along with editor Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), Trent sets out to locate Hobb’s End, the mysterious New England village they suspect Cane has retreated to. As they progress aspects of Cane’s books seem to blur into their reality – the village they arrive at appears to be an uncannily exact replica of the setting of Cane’s latest novel, they stop at a hotel seemingly run by one of his characters – and the suspicion that they may have wandered into a piece of fiction creeps in.

For all the Lovecraftian schlock and rubber monsters that follow, it’s this self-narrating component which distinguishes In The Mouth Of Madness, at times pulling the film into Dennis Potter country. “Cane’s writing me,” Styles tells Trent during a botched getaway. “He wants me to kiss you. It’s good for the book.” This combination of B-movie fun and dizzying meta-fiction makes the film something of a companion piece to Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, another mid-90s tale of lowbrow storytelling intruding onto the everyday. I’d hazard it’s also one of the reasons why the film, although critically panned in the U.S. on its original release (“a really bad movie” was how The Washington Post summed it up), was relatively well received in Europe with Cahiers du Cinéma listing it as one of 1995’s best films.

Carpenter claims In The Mouth Of Madness to be the final installment of the Apocalypse Trilogy, preceded by 1982’s The Thing and 1987’s Prince Of Darkness. Aside from an interest in the end of the world and similar critical maulings, the most obvious thing which unites these three films is Carpenter’s knack for surreal imagery, the shock of which lingers long after the end credits: a reader of Cane’s latest book crying tears of blood after finishing it; a gang of children with distorted, rotting faces; a naked man shackled to the ankle of homely octogenarian Frances Bay (a David Lynch stalwart). But it’s his quieter moments which have the most lasting impact. As any fan will attest, one of the films most disquieting moments is simply an elderly man riding a bicycle.

Richard V Hirst

Radio Days (Woody Allen, 1987)

For this writer, Radio Days is the Woody Allen film that’s most likely to be pulled from the shelf and savoured like a special treat. On surface level it may not have much to recommend it: Allen is absent as an actor, and an episodic film based on his Brooklyn upbringing in the 1940s is hardly the stuff of scintillating pitches. Yet look closer and this is one of Allen’s warmest and most human of films.

This story of immigrant family life juxtaposed with the radio stars of the day is told through the eyes a child and therein lies much of the film’s charm. The adult characters, while not without their flaws, are viewed with affection. These are people trying to make ends meet and as much as they rely on each other for support, they frequently turn to the radio for a momentary and all too brief escape. The characters offering this escape – breakfast gossip show presenters, superheroes, quiz masters and, most touchingly of all, Sally White, the aspiring radio star – are presented through anecdotal episodes.

The stories of the family members run parallel and intertwine throughout the film. Indeed this is one of Allen’s most ambitious screenplays. Devoid of cynicism, this is a film that captures family life at its best. Frequently funny, sometimes sad and touching throughout, Radio Days offers a comfort rarely found in the adult world.

Julian Marzalek

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

Released in 1997 Jackie Brown was hailed as a comeback movie for Pam Grier and Robert Forster, and to some extent it was. The film was Tarantino’s third full length feature, and an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel Rum Punch. By far one of my favourite Tarantino films, it managed to hold on to the director’s unique style, but with a script and visual aesthetic that was pure seventies. It avoided much of the graphic violence Tarantino had become known for, and proved that he was a master of dialogue and plotting. Yet in the car scene between Ordell Robbie and Beaumont Livingston, when Beaumont is “let go of” the dark Tarantino humour is still there and flourishing.

To see Pam Grier back on screen was to understand her influence as an actor back in the seventies. She was still powerful, charismatic and commanded every shot she appeared in, and to a younger audience was a revelation of sorts. This was the ’90s and the strong female lead was still an exception and not the norm. Combine with Samuel L Jackson at his finest, and a comedic performance from Robert De Niro, and this underrated film becomes a classic. It may not have had the fan fares or coverage of Reservoir Dogs or Pulp Fiction but for me it is a film you can watch time and time again, picking up on different nuances with each viewing. You also cannot discuss Jackie Brown without mentioning one of the great movie soundtracks. From Bobby Womack, to The Delfonics, to Johnny Cash, to Pam Grier’s own ‘Long Time Woman’ from her 1971 film The Big Doll House. Every song is looped in with perfect timing. Without the soundtrack the film would not have been the same.

Lisa Jenkins

Bangkok Dangerous (The Pang Brothers, 2008)

Many film and pop culture commentators have made valiant efforts to redeem some of Nicholas Cage’s later works. For example, whilst universally panned at the time of its release, The Wicker Man (2006) has now entered into a cultish afterlife. Cage’s dumbfounding and outrageous performance making the film a self aware guilty pleasure. Nestled within his later films are a few other gems, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, (2009), Kick-Ass (2010), and Joe (2013). Other than that there is little redemption to be found.

The Pang Brothers 2008 film Bangkok Dangerous (a remake of their own 2000 original) seems like an obvious contender for scraping the cinematic barrel. A story of a glum assassin called Joe who is called to Thailand for one last hit, but whose humanity suddenly begins to show itself when he meets a young female pharmacist called Fon who is deaf and mute. Although it breaks his own rules, Joe is clearly taken with Fon because the communication between them is the first innocent encounter he has had in years. He also takes on a local thief, Kong, as an apprentice, a move which also directly violates his strict assassin code.

The film was critically mauled at the time release, and bombed at the theatres. Many reviews criticized the dull and subdued colour palette of the film, due to which one of the most vibrant locations in the world is drained of colour and placed under gloomy neon purples and blue hues. The film is almost exclusively set at night, when the action takes place in daytime the light is so bleached the sun may as well not be shining. The story may be run of the mill, but because of the stylisation the film feels sublime. It achieves the feeling of what it’s like to be alone in a foreign place, sleep deprived, jetlagged, unable to communicate with those around you, unfamiliar with the local customs. Think Lost in Translation (2003) meets Only God Forgives (2013) meets Collateral (2004). It’s been noted that Cage’s performance lacks dynamism, yet with the film feeling so out of sync his performance strangely fits his surroundings. Joe is lost, bewildered, and utterly alone. Bangkok Dangerous may not set pulses racing but it is something rare: an existential action movie.

Stephen Lee Naish

Tideland (Terry Gilliam, 2005)

My first time viewing of Tideland was made extra-special because I had a chance to meet and speak with director Terry Gilliam – but I came away even more impressed with the film itself. Despite being Gilliam’s most personal film since Brazil, it was released to almost universally bad reviews—people like A.O. Scott of the NY Times called it “creepy and exploitative,” when it is actually a very tender film about a child’s imagination, that just happens to deal with heroin and the death of a parent. It becomes a poetic tale that might be better described as Flannery O’Connor does Alice In Wonderland. If anything, the fact that the critics hated Tideland so much has made me latch on to it even more.

Featuring Jodelle Ferland as Jeliza-Rose, a young girl left to fend for herself by feckless parents – Jeff Bridges and Jennifer Tilly – the performances are fantastic. It’s a testament to Bridges’ acting that he is dead throughout most of the film but his presence is still felt. Brendan Fletcher absolutely transforms into Dickens, a young mentally impaired man who becomes Jeliza-Rose’s friend.

Produced by Jeremy Thomas, one of the few producers willing to constantly take risks on subject matter throughout his career, it requires an open mind on the part of the viewer. Like all the best fantasy films, Tideland is seen through the eyes of a child. You should see it, if only to form your own opinion.

Ian Schultz

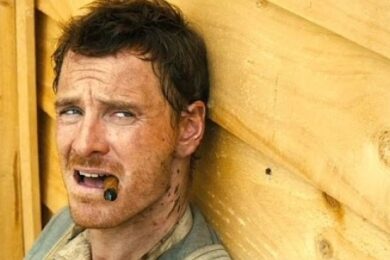

Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976)

In this deliciously slapped together ‘Ozploitation’ flick, a drunk Dennis Hopper plays the notorious nineteenth century bushranger Dan Morgan, who, as it turns out, was actually drunk most of the time he held his victims up. Shooting in cold blood a station hand who refuses him a cask of rum, and wanted for the murders of a few mounted troopers, the feared Morgan made a bizarre but strangely fitting choice for Hopper, who had notched a string of B-grade lead roles together in between the dizzy heights of Easy Rider (1968) and Apocalypse Now (1979).

Perhaps to get into the mindset of his character, but also because there’s probably not much else to do in the middle of the Victorian bush, rum was the favoured drink of choice for Hopper on set, and he became notoriously hard to control in between takes, mirroring the wild exploits of his protagonist in every measure. The film starts off with a title sequence that could have been plucked from the silent era if not for David Gulpilil’s digeridoo playing sailing over the top, and then turns to a gold panning party who are ambushed by the river, from who Morgan – busy enjoying opium on his break – escapes and finds haven in the bush. He goes on to lead a life of petty theft and casual murder, aided by an Aboriginal tracker – played by Gulpilil – who, tending to one of his gunshot wounds, teaches him how to survive on his own in the harsh country.

The film is odd and stirring for a number of reasons. To start with the cinematography is stunningly bad, and the editing makes it look like a ‘lost film’ for which the remaining reel was never found. But Hopper is extraordinarily believable as Morgan – perhaps because he pretty much tried to be the Bushranger on set, as if he took on the role as both an exotic holiday and a full-blown character study financed by the Australian Film Commission. Regardless, Mad Dog Morgan punches above its weight on every count – a lot of Oz new wave flicks lacked formidable star power in their lead roles – and wisely refrains from romanticizing the bushranger as anything other than most of them really were: lifetime thieves who survived on a blood thirsty distaste for authority figures.

Raphael Hall

Beat (Gary Walkow, 2000)

There’s been a resurgence of interest in the Beat Generation in recent years, with no less than four major films released on the subject since 2010. But translating what it was to be Beat for the screen has never been straightforward. There’s a too-common tendency to resort to cliché: soaking the films in smoke and jazz; stereotyping the movement as something akin to mere youthful rebellion and experimentation; toning down the characters’ challenging, often immoral behaviour to make them as near as possible to Hollywood-ready. Walter Salles’s On the Road, for example, was guilty in 2012 of reducing Jack Kerouac’s iconic and complex journey across America to little more than a raucous, overly self-conscious travelogue.

Despite the odd worthy effort, such as David Cronenberg’s delirious take on Naked Lunch in 1991, Carr, Burroughs, Kerouac and Ginsberg have come to represent something of a poisoned chalice for filmmakers. This is why Gary Walkow’s underrated Beat – an appropriately pure title – is such an achievement. It’s a pared-down, aptly budgeted look at the period between Lucien Carr’s killing of David Kammerer in Riverside Park and the death of William Burroughs’s wife, Joan Vollmer, in Mexico City. On the night of Vollmer’s death, Burroughs points his gun at a glass balancing on her head, his hand trembling. At this stage, he’s on the periphery of a career in writing. “I dare you,” she breathes.

Shot on location and treated by Walkow much like a poetic docudrama, the main action takes place in Mexico and tracks the breakdown of the central relationship. Following Carr’s release from prison, he and Ginsberg join Vollmer in the capital city and set off on an impromptu foray in the direction of an erupting volcano, while Burroughs is in Guatemala with his lover, Lee. Drifting through an ethereal, wild landscape, accompanied by a beautiful score, the friends – brushed with love, lust and madness – hurtle together towards inevitable destruction.

Almost everything about the feature is strange and slightly off-kilter. The casting of Kiefer Sutherland in the role of Burroughs, for instance, is confusing, but his restrained and skittish energy works. Courtney Love, on the other hand, plays Vollmer with a freewheeling carelessness that abandons any notion of realistic portrayal; she simply blows through the film like a force of nature. The quality of Beat, therefore, doesn’t lie in its accuracy as such, but rather in its spirit and ethos. By working in his subjects’ wake, Walkow has achieved something miraculous: he’s made an extremely good film about the Beats, for which he deserves considerable praise.

Tim Cooke

Stranger Than Fiction (Mark Foster, 2006)

It’s ironic that a film about a man who lives the most forgettable life for 12 years should be, almost 12 years later, forgotten itself.

Will Ferrell’s insipid IRS agent, Harold Crick, wakes up one day to the voice of Emma Thompson’s fraught novelist inside his head, narrating his life and foreboding his impending death.

With such an intriguing premise, it is a surprising shame that Stranger Than Fiction is a film that simply got lost in the mid-2000s. Perhaps being released at the same time as the headline-grabbing Borat, which was number one at the US box office at the time, and Casino Royale, the new Bond film with a controversial new casting, was simply too much for a quiet film about a quiet man.

I was fifteen when I first watched Stranger Than Fiction. At the time I appreciated its intelligent take on the idea of a character that knows he’s in a story – it felt like a fresh approach to English literature, a subject I was struggling to find appealing at school.

On second viewing I picked up more on the warmth of the film. Peel away the high concept and what you see is a small group of people trying to make the most of their lives. Ferrell is excellent as the unremarkable Crick, especially as it was his first dramatic performance. He gives a subtle performance that prevents the film from becoming absurd or the character farcical. His interactions with Maggie Gyllenhaal’s Ana, whose life of unpredictability nicely counters Harold’s life of banal routine, range from comic to deeply moving. This central conflict of themes becomes quite real when, on the advice of Dustin Hoffman’s Literature professor Hilbert, Harold tries to work out whether his now narrated life is a comedy or a tragedy.

However, it is only very recently that I realised just how good Stranger Than Fiction is and how well it tackles life and the importance of making the most of it. Many films try to tell this story but few succeed, instead devolving into nothing deeper than an inspirational poster. Stranger Than Fiction eschews grand statements, instead focusing on the intimate, smaller goals in life that actually matter the most: telling someone you like them with ‘flours’, watching Monty Python in the cinema during a weekday, learning a song on an instrument that you secretly wanted to master years ago. The fact that the film spends two minutes explaining why Harold chose a specific guitar is a testament to its dedication to the little things.

Stranger Than Fiction is a film that is very much like its protagonist: at first it may appear unremarkable, but pause for a moment longer and you’ll discover a warmth and intelligence that will attract you time and time again.

Ben Rabinovich

First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982)

Sylvester Stallone had a habit of starring in long running series with stellar first instalments, that devolved into ever more ludicrous, ever more jingoistic camp. The original Rocky gets its due as being a legitimately great film, but First Blood is so tarnished by the ludicrous – if not unenjoyable – excess of its deeply silly sequels, that it doesn’t often get a fair shake.

First Blood is a top notch action film, and indeed far better executed than its overcharged sequels, but there’s also a complexity here that at times makes it feel more of a piece with the pessimism of the New Hollywood era than it does with your usual breezy blockbuster. Director Ted Kotcheff, responsible for cult Ozploitation classic Wake In Fright, brings a lot more style and skill to the proceedings than his franchise successors would.

John Rambo, the troubled yet supremely capable Vietnam vet played by Stallone, is pretty much synonymous with the most dunderheaded qualities of action cinema in the Reagan years. In the later films he’s a great big hunk of patriotic all American meat that heroically solves problems by lobbing grenade tipped arrows at foreigners.

The John Rambo in First Blood is very different. Rambo is a troubled loner and drifter, who lashes out with extreme violence, and is quite blatantly afflicted with severe PTSD. He’s not exactly an inspirational figure. He wanders into a small American town and is quickly arrested on trumped up charges by the smug and petty local sheriff, played by a delightfully smarmy Brian Dennehy. Naturally, Rambo isn’t having it, so he busts out and more or less wages a one man war against the police.

It’s expertly paced and filled with fantastic set pieces and more or less non-stop action, but there’s an uncomfortable ambiguity to the conflict. The treatment Rambo receives is harsh, but the violent retribution he dishes out sits uneasily. A scene set in dark woodland, as Rambo hunts the pursuing police officers, plays like a precursor to Predator, with Rambo as the invisible monster. It all ends on a downbeat note, with Rambo breaking down and sobbing before turning himself in. The ultimate soldier is a broken shell of a man, destroyed and spat out by the military. It’s a far cry from the patriotic, borderline fascist triumphalism of the later Rambo films.

James Ubaghs

Mishima: A life In Four Chapters (Paul Schrader, 1985)

The directorial career of Paul Schrader has often been lost in the shadow of his more famous contemporaries (Altman, Lucas, Scorsese, Spielberg et al), but it is a remarkable body of work. From Hardcore and Blue Collar to Light Sleeper and Affliction, Schrader’s films are fierce, often gruelling depictions of the darker realms of the human condition, especially those regarding masculinity. Schrader’s 1985 film Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters, is a multi-layered treatise about the life and work of Japanese author Yukio Mishima, interweaving elements from his extraordinary literature (especially from his Sea Of Fertility tetralogy) and his controversial life story to realise both the man and his place within Japanese society.

Veteran actor Ken Ogata gives the performance of his life as Mishima, a man conflicted by post-war Japan and the schisms of his own sexuality. The muted colour palette of the contemporary scenes and flashbacks contrast with highly stylized evocations of key episodes from Mishima’s work, emphasizing the abyss between his life’s work and the infamous ‘coup’ attempt and public suicide that secured his infamy. To this day Yukio Mishima is so controversial in Japan that he remains almost a non-subject, and sadly Mishima remains unreleased in that country. Schrader himself said of the film that “…it’s the one I’d stand by – as a screenwriter its Taxi Driver, but as a director it’s Mishima”. Blessed with a mesmeric soundtrack by Philip Glass, Mishima is one of the most outstanding cinematic works about the creative process ever made.

Kevin McHaighy

Funny Games (Michel Haneke, 2007)

When it comes to dividing the room, you couldn’t ask for a better exercise in splitting opinion than watching Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (2007) – a much derided shot-for-shot remake of his 1997 film of the same name. Arriving in cinemas at a time when the so-called ‘Torture Porn’ school of horror was very much in vogue, some saw it as an exercise in on-screen brutality that ate its cake and then rewound the tape and had it too. The film is famous for a number of interpolations given by Peter, a sociopathic home-invader, who breaks the fourth wall, speaks directly into camera and chides the audience for watching the gruesome goings-on that he happily perpetrates. If it sounds a touch hypocritical, that’s because it is.

For some, these interpolations were too loathsome to take seriously and represented the sort of condescension and moralizing normally aimed at horror films from the outside by reactionary critics who are simply hostile towards the genre. If you take that view, then Haneke’s decision to voice that attitude from within the film marks him as a type of hypocrite and traitor – making a cruel horror film whilst taking great care to remind his audience that, of course, he’s really above that kind of thing. Loathe it or not, however, you can’t escape the impression that, when Peter turns to the audience and asks us why we’re still watching all this violent nastiness, he genuinely wants to know the answer.

Indeed, one of the film’s strangest qualities is the complete earnestness with which Peter interrogates our interest in what he’s doing. Michael Pitt delivers Peter’s lines in a soft, indolent tone that can sound snide, but also sounds genuine in the way that only true disinterest can be. The effect is reminiscent of Blue Velvet (1987), a masterclass in creepiness that also draws considerable power from the combination of innocence and psychopathy. Rather than detracting from the fun of horror, the attempt to implicate the audience makes matters all the more enjoyably absurd. Peter is a sadistic killer whose only motivation is the fact of his being in a horror film – he’s doing his bit, is the audience doing theirs? Are we entertained? It seems like a fair question. Peter’s asides don’t feel like a pompous exercise in meta-theatre because they don’t truly succeed in alienating the audience, they’re more like a bit of pantomime joshing.

The most overlooked aspect of Funny Games is that, in its own ludicrous way, it really is funny. The fact of its being a remake added fuel to the fire of haters who saw it as a cynical cash-in on the ‘Torture Porn’ vogue, but arguably its timing couldn’t have been better. Here was proof that, years before ‘Torture Porn’ was being cooked up, Haneke (intentionally or not) had found a more intriguing way of warping the horror genre, and offending the ‘good taste’ of horror fans themselves, all in the name of awfully unclean fun.

Tom Duggins

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Peter Hunt, 1969)

This, the sixth film in the long running James Bond franchise and the first and only outing by George Lazenby as Ian Fleming’s spy, has come to be treated by its creators in much the same way that the Royals treat their mad relatives: as something to be locked away and never mentioned again.

A crying shame, really, because repeated viewings of this rarely considered film reveal it to be the best James Bond movie. There are two key components to the film’s success: the material and a sense of vulnerability. As with the best moments of the series, the film follows Ian Fleming’s novel closely. Fleming’s protagonist was far from the superman often portrayed on the screen – here was a fallible human being open to danger that, as often as not, would either fuck his mission up or end with him severely damaged on both a physical and psychological level. And this is where George Lazenby succeeds in his portrayal of Bond.

A former fashion model and car salesman whose only previous screen experience had been appearing in Fry’s Chocolate Cream advert, Lazenby conveys vulnerability in a way that his predecessor, Sean Connery, never could. Without the usual array of gadgets from Q branch, this Bond is more physical and reliant on his wits than had previously been demonstrated. Lazenby’s performance has been slated as wooden but the fear on his face after his escape from Blofeld’s alpine base is palpable. Likewise, his reaction to his shock bereavement is both believable and touching.

Like AC/DC’s Powerage album, this isn’t a hopping on point for the casual observer but for aficionados of the series. The darkness and the grit of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, along with a hero all too susceptible to peril and emotional hammerings, is exactly what makes it shine and why it’s one of the best in the breed.

Julian Marzalek

Talented Mr Ripley (Anthony Minghella, 1999)

Though I’ve been assured it’s “middle-of-the-road” and a mere poor cousin to Purple Noon (the Alain Delon movie inspired by the same Highsmith novel), The Talented Mr Ripley still affects me like no other film I’ve seen. As the sun shines on a picture postcard Italy, there is ambiguity, and murder, and a portrait of a desperately lonely man acting under twisted, amoral impulse. Irresistible because it surreptitiously inserts director Anthony Minghella’s more macabre fascinations into a straightforwardly ‘Hollywood’ literary thriller, The Talented Mr Ripley is a satisfyingly twisted affair that begins cheerfully enough before bleeding out any warmth for the sake of increasing eeriness.

Matt Damon, a gleaming grin betraying a wealth of insecurities, is the pathetic, troubled Tom Ripley, a broke young New Yorker stealing the life of another seemingly against his own uneasy will. The man Tom befriends and comes to obsess over is playboy Dickie Greenleaf, smugly played by a never-better, never-more-desirable Jude Law. Their relationship takes the film to interestingly skewed places: does Tom desire Dickie sexually? Does he crave his companionship, maybe even his brotherhood? Or did Tom always want to be Dickie, in the hope that absorbing the character of an outwardly content, confident man would banish his own feelings of inferiority and isolation?

These questions permeate The Talented Mr Ripley – they fester, corrupting Minghella’s vision of a dreamy 1950s Europe. Slowly we come to realise this shiny Hollywood bauble has rotted at the core. It’s not a thriller, but the coming-of-age story of a sociopath. The Talented Mr Ripley doesn’t strive to moralise, which is what makes it so uniquely troubling for a mainstream film: our lead is an opportunistic killer and con artist, but at no point are we made to judge Tom or side with the authorities rightly trying to apprehend him. Ripley isn’t one of cinema’s perversely charismatic and charming psychos, either – he’s someone to pity, but never someone to actually like. The director saves a final sympathy-killing twist for the very end, but by that point you’re complicit in all Ripley’s worst crimes, a willing voyeur, appalled by his actions but exhilarated by the abandon of a character with nothing to lose.

Brogan Morris

Hideous Kinky (Gillies MacKinnon, 1998)

Hideous Kinky is the intriguing, perhaps offputting title of Esther Freud’s autobiographical novel. But it’s only offputting until you know what the words mean. They’re a chant, a children’s game that’s a recurring thread through Freud’s story, which is framed as the recollections of a little girl whose mother takes her and her elder sister away from their life in England to live in Morocco in the ’60s. ‘Hideous’ and ‘kinky’ are the girl’s favourite words, and they use them like a kind of mantra, a little scrap of private language between them. It’s a shortcut, an instant way into the children’s world.

Gillies Mackinnon’s film version retains the title, and the children’s mantra runs through it like a rhythmic punctuation, just as it does in the book. It opens with Freud’s character, now named Lucy (Carrie Mullan), whispering “Hideous kinky, hideous kinky,” to comfort herself while travelling through the strange North African landscape. This sets the tone for the film, which does its best to inhabit the children’s viewpoint just as the book does, filtering much of the story through their experience of Morocco rather than the adults’. This choice works, because the little girls are terrific, and the balance between what they can and can’t understand of the adults’ concerns is delicately and expertly handled. The adults are great, too. Kate Winslet plays the mother, here called Julia, with characteristic verve, and French star Saïd Taghmaoui is brilliantly charming and contradictory as her unreliable Berber lover Bilal. But it’s the girls’ experience, and while it’s a vivid one, full of noise and colour and music, for little children used to London life, it’s as overwhelming as it is liberating. Bea, the elder sister (Bella Riza), just wants to go to school – her sarcastic, angry commentary on the family’s lack of money and embarrassment at her mother’s behaviour perfectly undercut Julia’s relaxed attitude and quest for spiritual enlightenment.

MacKinnon’s subtle direction lets Hideous Kinky live up to its name – it has a rhythmic, dreamlike quality that evokes childhood’s love of repetition, and this shifts in places into the feverish patterns of nightmares. Morocco is both dream and nightmare for Lucy, Bea and Julia, but the idyllic dream is more powerful, and when the journey – and the dream – is over, it’s deeply, surprisingly heartbreaking. Hideous Kinky wonderfully evokes the sense of nostalgia and regret that can accompany memories of both travel and childhood, and it does a fine job of bringing Freud’s beautiful novel to life. Offputting title or not, it deserves to be seen more often.

Yasmeen Khan