Welcome to Injustice For All, a semi-regular feature here on The Quietus in which we ask our writers to nominate their choice of underrated film and to argue its case. For this instalment James DC takes up arms in defence of Mike Hodges’ paranoid sci-fi thriller, The Terminal Man.

For unknown reasons Mike Hodges’ The Terminal Man remains underrated and has yet to acquire the cult status it may be expected to have attained. Based on the novel of the same name by Michael Crichton, known for co-creating crowd-pleasing blockbusters like Jurassic Park (1993), but who also wrote and directed that other cult SF film, the brilliant Westworld (1973). The Terminal Man should be better known and comes second only to director Hodges’ justly celebrated masterpiece Get Carter (1971).

Ostensibly, The Terminal Man is a science fiction film, but of the more subtle, minimalistic kind. In some ways it’s a mood piece, relying more on the pared-down symmetry of the visuals and measured pace than outright plot, action or dialogue. Indeed, it is very of its time: that rather odd, shifting period in Hollywood – roughly from the late 1950’s up to the advent of box office successes like Jaws, in 1975 – when the big studio corporations were forced, for various reasons, to give way to more independently structured, lower budgeted films. The Terminal Man came out of that same zeitgeist, some of the best films of which were preoccupied with government corruption, surveillance and espionage, especially around the time of the Watergate scandal. Such highly atmospheric, portentous yet rather detached films as The Manchurian Candidate (1962), The President’s Analyst (1967), The Conversation (1974), and The Parallax View (1974) were of this ilk. With their adroit ethical dissections of government and corporate funded violence and control, as well as the societal dangers of encroaching technology, these films employed, ironically, that very technology’s gadgetry and special effects in order to pose such pressing questions via the style and aesthetics of the cinematic medium. Conceptually, and artistically, these were the ‘Mobius Strips’ of the movie world, and The Terminal Man, is undoubtedly a part of that peculiar cultural continuum.

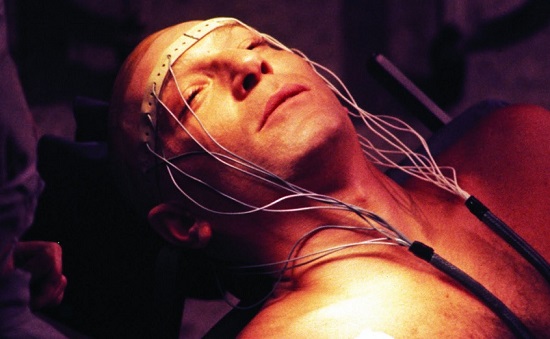

The film’s story is simple, but highly effective: Harry Benson (George Segal) is a computer scientist, who happens to think that computers and advancing Artificial Intelligence will gradually take over the world. He suffers from a form of epilepsy which sometimes causes him to black out and become uncontrollably violent, later oblivious to the abuse he has committed. So, he volunteers as a human guinea pig for state-of-the-art surgery, having computer-controlled electrodes implanted in his brain in order to control his violent seizures. However, the artificial melding of automatically dispensed sedatives, computer gadgetry and his primal, unconscious emotions causes a dangerous malfunction, whereby he rapidly undergoes fits of increasingly extreme violence. He escapes from hospital and then goes on the run after the compulsive murder of a prostitute. He then attempts to attack his female psychiatrist at her home, and his situation spirals out of control thereafter. It’s best not to spoil the ending, suffice to say that it is tragic, poignant and nihilistic.

Over the first hour or so, the viewer sees the medical preparations and the surgery for the insertion of the brain implants. In one sense nothing much happens, yet it’s riveting as the small details, minutely observed, are played out by the hospital staff. Similar medically based scenes, shot in a semi-documentary, precise style, feature in films like Fantastic Voyage (1966), The Boston Strangler (1968) and even the Woody Allen comedy, Sleeper (1973), where the locations are bright-white and antiseptic, everyone seems very clinical and aloof, and there is an audience of medical students watching from above in an auditorium. (Perhaps the origin of such ‘spectator surgery’ scenes comes from A Matter of Life and Death (1946). There is almost a mini-genre made up of such films, but that is for another article).

As with many of the characters in the aforementioned ‘paranoid’ films, the protagonist’s gradually fragmenting personality is reflected, quite literally, through windows and mirrors, or the intermediary transmissions of monitors. The symmetry and clean, minimal spaces of the mise-en-scène simultaneously reflects, yet belies, Benson’s deteriorating state of mind, and The Terminal Man is a prime example of this 1970’s motif. Moreover, the ingrained superciliousness of the surgeons and doctors, whilst Benson’s female psychiatrist is the sympathetic conscience of the medical establishment, is symbolic of the wider ramifications of sociopolitical unrest in American society at the time, and boils down to a case of the ‘straights’ versus the ‘counterculture’, a prevalent theme in films of the era.

Dressed in a white suit and incongruous wig, Benson, during his violent seizures, rolls his eyes and grimaces like a veritable monster from the id. He is just a normal, ‘nice guy’ gone bizarrely wrong, and it is disturbing to see. In the central murder scene – whilst eerie sounds emanate from a television set which plays the science fiction classic Them! (1954) – Benson descends into a kind of trance, and, like a tin robot repeatedly bashing into the wall, his arm continues the repetitive stabbing motion into the waterbed on which his just-killed victim lies. He has turned into a rampaging automaton, a precursor (along with Crichton’s earlier Westworld) to later demonic robots like the T-800, from The Terminator (1984). As the victim’s blood seeps onto the white, tiled floor, the red rivulets flow through the grooves like electricity through a circuit board or signals through the neurological pathways of a brain. A later scene, when Benson smashes partly through a bathroom door to get at his victim, predates the famous ‘Here’s Johnny!’ sequence from The Shining (1980). The same scene also subtly references Psycho (1960), a type of cinematic ancestor. It’s as if Benson encapsulates the evolution of the archetypal demented villain from ‘ordinary’ human to intermediary human/robot hybrid, where unbidden psychosis is embedded in more obscure, liminal spaces; the loaded and as yet unmapped pathological juxtaposition between the primitive and the ultra-modern.

Despite Benson’s horribly violent acts, we are still sympathetic towards him. This is partly because he has the trustworthy, likable face and demeanor of George Segal, who plays out of character, in a serious, nuanced role for the time. But more importantly, we know that he is an innocent victim of the ‘Frankenstein Complex’ – the pitfalls encountered by humanity when it arrogantly tries to play God with nature.

The film works on a number of levels beyond entertainment. Primarily, it evokes a sense of foreboding about the ever-increasing intermingling of human industry with burgeoning technology. Obtusely commenting upon corporate power and the constraints society-at-large tries to impose upon individuals via technology, i.e. the controlling aspects of myriad cybernetic interface systems which go toward subtly enforcing a slave mentality in the masses. Such problems are even more of a worry nowadays, with people addicted to the hyper-tech virtual world of the internet – they may as well be directly ‘plugged-in’ like Benson is. The Terminal Man, then, was – like other, similarly themed science fiction films of the period – highly prophetic. One of the film’s greatest assets.

Implicitly warning of the encroaching dangers of untested technology on the human biological system, the coda to the film shows a peephole to an asylum cell, surrounded by darkness. A medical warder looks through the hole and calmly but sternly says, as much to the film’s audience as to anyone else: "They want you next".