“As a German filmmaker after the war, we grew up as – not only me, but all my peers – we grew up as a fatherless generation – as a generation of orphans. Our fathers either had fled the country, were chased out or they had sided with the barbarism of the Nazi regime. So we had no one to learn from, and we started to look out for our grandfathers. And that was Murnau, Fritz Lang and others. So I just needed to connect myself with a culture, with a legitimate, great culture of Germany. And that was the culture of the grandfathers or even earlier than that.” – Werner Herzog.

Herzog’s remarks bear striking resemblance to the underlying sentiments of the “Krautrock” generation, reminding in particular of Ralf Hütter of Kraftwerk’s comment that “we had no fathers”, and of Kraftwerk’s own desire to reconnect with the aesthetics/ethos of the Bauhaus movement, terminated by the arrival of the Nazis in 1933.

Herzog was a leading light in what was known as the New German cinema, an avant garde of young filmmakers who also included Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Alexander Kluge. The parallels between them and the similarly emergent Krautrock musicians are both striking and inevitable. Both tended to have been born around the time of the Second World War, coming of age in the late 1960s, at a time of general political insurrection but particularly conscious of the dreadful schism in Germany’s recent past. Both were concerned about the “Americanisation” of West Germany, a sort of cultural occupation, with landscape and existential uncertainty. Both stood in contrast to banally amnesiac strains in their chosen media – for Krautrockers it was the hideously kitsch form of MOR known as Schlager, for filmmakers it was “Heimatfilm”, a form of cinema which offered a bucolic, nostalgic view of a never-never Germany in which the Third Reich had never happened. And, despite being lumped together under single monikers, both groups contained very diverse members, whose common characteristic was a desire to innovate, to find new modes of self-expression at a vital point in German cultural life.

There was only a limited amount of intersection between the two groups, however – Can’s Irmin Schmidt wrote film music, for instance, but along with the rest of his group, and his musical peers generally, he was primarily concerned with creating visions of his own through music, rather than playing a more subordinate, soundtracking role in the pictorial efforts of others.

However, the working relationship between Herzog and his friend Florian Fricke and his group Popol Vuh would prove to be a fertile and mutually beneficial one, which enhanced both the work and the reputation of both. Among the films in which they collaborated are Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Heart of Glass (1976), Nosferatu (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982) and Cobra Verde (1987), which are among the 16 Herzog films currently being reissued in remastered form on blu ray by the BFI – a list that also includes The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser, in which Fricke contributes musically and makes a cameo appearance.

Fricke had first met Herzog in 1967 and the following year played a cameo role in Herzog’s movie Lebenszeichen (Signs Of Life), about three German soldiers assigned to a Greek island. However, oddly enough, it was a film in which Fricke and his music did not feature in any way in which a strong connection was made – 1971’s Fata Morgana (whose title means a “superior mirage”).

From its superficial, stoner appeal, to the method of its making, to its structure,Fata Morgana could be described as the quintessential Krautrock movie. Called an “Expressionist documentary film” by Herzog, he shot the footage for it in the southern Saharan region of Africa, before he decided what kind of film he was going to make (at one point, he considered making it a sci-fi movie). What eventually emerges is an unending, desert Dystopia, in which both the smallness and the grandness of man and his dreams are emphasised, interspersed with bizarre motifs such as wrecked cars, buzzing planes, a lecture about turtles and a couple playing drums and piano in a brothel. Over this, the film is sectioned into a grand narrative design, sub-divided as “Creation”, “Paradise” and the “Golden Age”, a narrative which bears ironically scant relationship to what’s happening on screen. For Fricke, however, an important point of connection was the film historian Lotte Eisner’s narration of parts of the Popol Vuh, the creation text of the Quiche Indians of Guatemala.

Florian Fricke was one of the more monied musicians of his generation, so much so that he could afford to buy himself a Moog synthesiser, a prohibitively expensive acquisition at the time – for most musicians, “electronics” meant attaching cheaper, modifying devices to conventional instruments. Being relatively free from material worries also meant he could devote more contemplative time to higher, non-materialist issues. For him, the “revolution” of 1968 was as much a spiritual as a political one. “We have discovered the Eastern part of this globe,” he said. He embraced free jazz, particularly John Coltrane who had his own, Eastern leanings. He took on board the great founding religious myths of the world – the Popol Vuh, certainly, but also the Bible and the Bhagvad-Gita, the Hindu scripture. In his own thinking and the spacious, liturgical tones of Popol Vuh’s early, synth-driven music such as Affenstunde, he ascended to a pan-religious stratosphere in whose clean air one could begin anew and put behind the terrible past. He would even abandon his synthesizer eventually, passing it on to a grateful Klaus Schulze, declaring that he preferred the “purity” of acoustic instruments.

All of which made him an odd match for Herzog, whose work seemed deliberately to avoid such serenity. As well as Fricke, another frequent collaborator for Herzog was Klaus Kinski, the devil to Fricke’s angel, Herzog’s “best fiend”, whose anti-heroic performances doubtless fed on the actor’s genuinely debased nature and often appalling on-set behaviour.

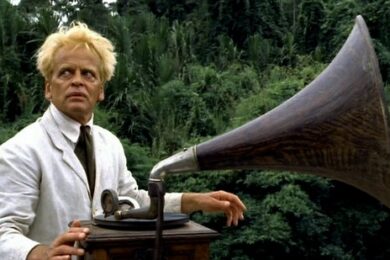

If Fricke’s work is about spiritual ascent, the films he made with Herzog (and Kinski) are often about earthy descent. Take Aguirre, The Wrath Of God, made in 1972, and Fitzcarraldo, made ten years later. Aguirre is set in the 16th century, following the annihilation of the Incan empire. It follows the journey of a band of conquistadors, including Kinski as Don Lope De Aguirre, as they set out in search of the mythical El Dorado, the City of Gold, a myth invented by the native South Americans they subjugated. The journey is a treacherous and doomed one, driven by delusion, greed and conceit, in search of a non-existent place. Fitzcarraldo ventures into a similarly Conradian heart of darkness – it’s set in the middle of the jungle around the turn of the last century and tells the story of Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (aka Fitzcarraldo, again played by Kinski) and his dream of staging an opera bringing together Sarah Bernhardt and Enrico Caruso. To raise the money for this venture, he must reach and exploit a vast area of rubber trees beyond the Ucayala falls, hauling his steamboat over a mountain with the assistance of the Indian tribes, who are so mesmerized by the gramophone recordings of the great singers that they willingly assist him.

As I wrote in my book Future Days: Krautrock And The Building Of Modern Germany, “Everything about these tales runs in precisely the opposite direction to the music of Popul Vuh. (“Too much the darkness,” Fricke once muttered of the travails and disasters that were part and parcel of the making of any Herzog movie). Fricke’s music aspires cleanly heavenward, whereas Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre are on a downward journey, down the slopes of the Andes, through churning mud and the difficult headwaters. Popul Vuh’s music actively celebrates and pays homage to other cultures and their equal, relative value to Western Christianity. Aguirre is an imperialist conqueror of native peoples, Fitzcarraldo a man with no qualms about achieving wealth on the backs of the “savages” he exploits, impressing on them the dominance of his own, “higher” culture (opera) as he does so. Popul Vuh’s music strives for spiritual fulfilment, beyond the bounds of earth; Aguirre and his conquistadors descend deep into its most hellish thickets in search of fool’s gold.”

And that is what makes Popol Vuh’s soundtracks such an appropriate counterpoint. What Herzog admiringly described as the “choir-organ”, the mellotron-like instrument which dominates the soundtrack to Aguirre comes across like a chorus of onlooking Heavenly angels, a sad, wry commentary on the downward bound hubris and nemesis to which they bear witness. They also lend a certain grace, however, a sort of blessing upon proceedings and confer a validation of sorts upon Herzog’s own trials in actually making these films – as with Francis Ford Coppola and Apocalypse now, the real-life privations of the production make for a similarly arduous story to the one they tell on screen.

Similar motifs recur in Cobra Verde (1987), in which Kinski again plays a character bent on another attempt at dominion in a “darker” continent – a debauched Brazilian bandit bent on reopening the slave trade. In an echo of Fitzcarraldo, we see him with the tables having turned on him trying to pull a giant boat to water. Here, Popul Vuh’s solemn musical finale to his pathetic efforts sounds like a multi-ethnic celestial choir chiding him almost mockingly; pitiful, wretched, fallen creature that he is.

Fricke and Vuh did further great work on Heart Of Glass (1976), in which guitarist Danny’s Fichelscher’s playing comes to the fore – by this point, Popul Vuh were more conventionally “rock”, though as Klaus Schulze observed, Fricke’s compositions still followed “electronic patterns” in their structures. Certainly, the group’s pastoral, ambient strains, informed by Indian music, come to the fore in the film’s meditative landscape interludes, including the finale in which a sailor puts to water from the Skellig Islands, in search of an imaginary abyss beyond the ocean’s horizon.

Still more effective was Popol Vuh’s soundtrack for Nosferatu The Vampyre (1979), in which the music reveals great depths of light and shade. From pretty pastoral (in the breakfast room scenes, for example) to minimal; from gothic, as in the opening scene, filmed in the Guanajuato museum, Mexico, which features the mummified remains of the victims of an 1833 cholera epidemic; to the electric blue sequences in which Nosferatu assumes the form of a bat as he makes his attacks. I have never forgotten the simple yet utterly harrowing two-note choral motif devised by Fricke to accompany the scenes of a boat carrying a cargo of coffins downriver to Wismar – momentarily, all of the spirituality he invests in his work is suspended, as a bony figure points, like a Giacometti sculpture, towards an awful, impending horror.

Popol Vuh didn’t merely soundtrack Herzog’s movies – as with Bernard Hermann and Hitchcock, they were an integral part of the experience, without which the films would seem unsustainable, even incomplete. Although Fricke and co produced fine stand-alone work, the privilege of their association with Herzog has lent their music a power, a meaning and a purpose it might otherwise have struggled to possess. A marriage made in Heaven and hell indeed.