Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

She’s a society girl ballet dancer living in her daddy’s mansion, he’s an orphaned street dancing mechanic from the wrong side of the tracks. He needs to learn control, she needs to locate the fire inside; to start dancing from her heart. When they cross each other’s path they fall in love, scandalise high society, save a local youth club from closure, and invent an entirely new form of dance, one that combines the grace and flow of ballet with the fiery urban rhythms of street breaking. The film? Take your pick, there are about a hundred that follow that exact description, and it is a plot I will never tire of because I love dance movies.

Dancing and movies go hand in hand back to the medium’s inception, from Valentino’s tango in The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse, to Wild Style’s verite footage of 1980s New York breakers. Film is a perfect medium in which to not only present but to scrutinise dance. When we see good dancing on stage we are struck by its power and fluidity, but film allows us inside the process and its unblinking eye can unlock the different layers involved in a performance – emotional, technical, sexual – and hold them up to the audience’s scrutiny.

What with the BFI currently toe-tapping its way through a season dedicated to dance on film, we thought it might be a nice idea to ask our writers to provide us with their favourite cinematic booty shaking scenes. The results are wide ranging, thought provoking and come from all over the globe. No matter where you are, it seems, the dance goes on. Mat Colegate

Words: Mat Colegate, Yasmeen Khan, Rory Gibb, James Ubaghs, Michael Wojtas, Luke Turner

Cruising (William Friedkin, 1980)

Anyway you slice it William Friedkin’s Cruising is a difficult film. Hard to love, often incomprehensible and brimming with a weird hypnotic power, it’s reputation has not improved a great deal over the years and it’s generally considered to mark a kind of cut off point; that bizarre film that pinpoints the moment where Friedkin went from celebrated auteur to unbankable shambles. This is partly deserved, Cruising, quite frankly, is a mess, but it’s a weird, seedy mess and one that’s impossible to forget.

The plot is simple enough: A serial killer is preying on gay men in New York, so Al Pacino’s undercover cop is sent to infiltrate the city’s leather scene in order to smoke the killer out. However the film’s perceived lack of sensitivity to its subject matter bought howls of outrage from the gay community at the time, who had had quite enough of seeing themselves portrayed as limp-wristed serial murderers, thank you very much. Watching the film now it’s hard to blame them for their misgivings, but what saves Cruising is its focus on a scene and a point in time now lost to history. Friedkin trains his famously unflinching eye on the leather bars of a pre-AIDS New York and the result is prurient, salacious and fascinating.

The scene I’ve chosen to pinpoint is a famous one, mainly for all the wrong reasons. Steve Burns (Pacino), deep undercover, walks into a bar and coolly surveys the scene, Friedkin’s camera is careful to show the viewer everything that Pacino can see – sweaty tussling bodies on the dancefloor, a moustachioed dude greasing up his arm in preparation for the fist fuck he’s about to give to the chained leather boy before him. Pacino’s reactions are immaculate. You can see that he’s trying not to be shocked; that undercover work necessitates his treating the scene like one he’s seen a thousand times before, but you still sense his unrest and his struggle to accommodate what he’s seeing. He talks to the barman about a suspect, looks about to order a drink, when he’s approached by a hot guy in a sleeveless leather jacket who asks him to dance. Initially reluctant he takes to the floor with the handsome stranger, huffs on a handkerchief soaked in nitrous oxide and – HOO HAA! – goes f*cking bezerk.

Now, I think it only fair to point out that Al Pacino is not a natural mover. He has the stiff backed, side to side lurch of a man who has been deliberately missed off the invitation list to a lot of parties, but his efforts here are nothing short of heroic. Round and round he goes, like a sputtering toy robot, pumping his fists and shaking his head up and down. A sweaty, puffing mess of masculinity, watched on by his fellow patrons with what continues to resemble grim fascination all these years later. Indeed, in the wake of this incredible display, it’s impossible to understand why he doesn’t get rumbled. Never has a more undercover-fuzz-like performance been committed to screen. You half expect him to ask his dancing partner if he knows where he can get some “whacky baccy” because he wants to “turn on”. It’s hilarious and sums up both the brilliance and ridiculousness of Pacino – and actor I abhor and love in completely equal measure – in a simple minute and a half.

But it’s also supremely unnerving, a quality even more pronounced in the crackly VHS rip I’ve chosen to post: the flashing lights, the acres of unidentifiable male flesh writhing and tussling, the sharp cuts of faces in ecstasy – and having Al Pacino in the centre of it all just adds to this off kilter, dangerously woozy feeling. It’s the closest cinema has ever come to the actual head-tightening, warp spasm of having a massive draught on a bottle of room odorisers. Friedkin takes what is for many an alien environment and bleaches it of all compassion, turning a nightclub into a fuck-or-be-fucked nightmare pleasure-scape of hellish heat and brutal abandon. It’s still possible to argue that his portrayal is problematic, but it’s impossible to argue that it isn’t effective. Mat Colegate

Silver Linings Playbook (David O Russell, 2012)

Silver Linings Playbook is about how difficult it is to move on, no matter how hard you try. Pat (Bradley Cooper) is looking to “take the negativity and use it as fuel to find the silver linings”. He also wants to use Tiffany (Jennifer Lawrence) to get a letter to his ex, so he reluctantly agrees to be her partner for a ballroom dancing competition. Tiffany sees dancing as therapeutic; Pat rationalises it as romantic training for getting back with his ex.

What’s great about their first practices is that they mark a fundamental change in their relationship. For the first hour of the film, they’ve talked and talked, but they’re at cross purposes with one another. Dancing together, they start to communicate. Yes, it’s sexual too, but the physicality of dance is about more than that, it’s about living in the moment, and how concentrating on movement can help you let go of the burdens of the past.

By the time the competition comes round, it’s Tiffany that’s reluctant to dance, and Pat who, having realised where the silver linings are really to be found, has to persuade her. And this reversal may be a neat narrative trick, but it’s charming, and sometimes there’s nothing wrong with neatness when it works and the film’s earned it. Yasmeen Khan

The Colour Of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov, 1968)

I’m not sure if you’d describe The Colour Of Pomegranates as based around ‘dance’ per se, but it’s exquisitely choreographed: every ritual gesture, every facial expression, even every sound in Sergei Parajanov’s 1968 film is loaded with meaning. The film, a poetic interpretation and reflection on the life of the 18th century ‘bard of the Caucasus’, Sayat Nova, unfolds as a series of vivid, beautiful visual tableaux that feel like paintings come to life. Deep reds, blues and golds contrast against pale skin; actors move with studied, deliberate slowness, elevating the often mundane activities they’re engaged in to the status of poetic acts in themselves. The film’s soundworld is equally rich, again drawing its power from contrast. Aware of the power of silence, each sonic event – passages of traditional music, running water, brief phases of spoken word, the clang of metal on metal – stands out in vibrant, tactile 3D.

Taken by themselves these scenes are gorgeous, abstract treats for the senses and mind, rich in allusion and veiled meaning. But they acquire still more power in the context of the film’s overarching narrative – a dreamlike sweep across Sayat Nova’s entire life – and its history. The film was made by Parajanov, born in Georgia but ethnically Armenian, under Soviet rule. Dealing with politically charged subject matter, and doing so in a manner that departed decisively from the dominant socialist realist aesthetic of the time, he was considered subversive by the Soviet authorities, and only a few years after the film’s release was imprisoned for several years in a hard labour camp in Siberia. The Colour Of Pomegranates has since been hailed as a masterpiece; indeed, the highly stylised and expressive way it deals with the human body is just one of the many reasons why it lingers indelibly in the memory. Rory Gibb

Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991)

It may be stretching the definition of a dance scene -30 seconds of a nude man awkwardly shuffling in front of a camera – but there are few other “dance” scenes that come to mind that are quite as striking and horrifying as Buffalo Bill’s tuck between the legs antics in Jonathan Demme’s ever excellent Silence of the Lambs. It’s a grotesque, weirdly hypnotic, punctuation mark in the action, that masterfully ratchets up the tension before the final confrontation, and its one of the most memorable moments in an impeccably crafted thriller stuffed to the gills with memorable moments.

Part of its power lays in the incongruity of the music; the at the time incredibly obscure but genius Q Lazarus song ‘Goodbye Horses’. It’s a both haunting and ludicrously catchy slab of synth pop that’s gone on to become iconic in its own right, and its infectious melody is about the last thing you’d want to hear while trapped in the bottom of a well.

Hannibal Lecter may be a Lucifer like seducer with sophisticated classical taste, but Buffalo Bill is clearly the one with the better record collection. He really knows his shit when it comes to post punk and obscure synth pop. After playing ‘Goodbye Horses’ a snippet of a Flipper song can very briefly be heard, and he later blares ‘Hip Priest’ at full volume when hunting Jodie Foster in his basement. This human skin wearing freak would clearly be a Quietus reader.

Of course all the Q Lazarus in the world wouldn’t add up to much if not for Ted Levine’s brilliant and underrated performance as Buffalo Bill. He arguably pulls a Dean Stockwell in Blue Velvet; that is he steals the show and out-creeps the headlining iconic scenery chewing villain . He’s at once both chillingly inhuman and pitiable, and his uniquely odd tremulous voice is the stuff of nightmares. James Ubaghs

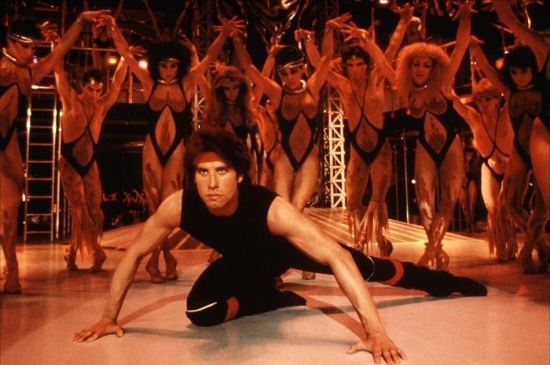

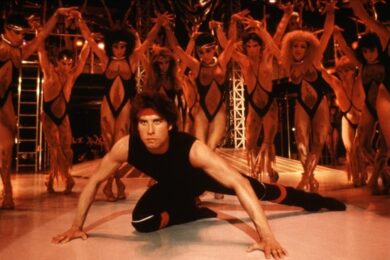

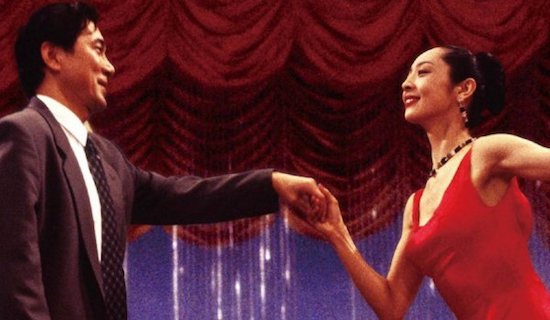

Shall We Dance? (Masayuki Suo, 1996)

Salaryman Shohei Sugiyama (Kōji Yakusho) is depressed; despite the happy family and the success at work, he wakes with a sigh in the morning. But from his grey commuter train, he glimpses a different world through a brightly lit window, a world of mystery and beauty and colour; soon, he’s taking ballroom dancing lessons in secret, and a new life is opening up for him. Shall We Dance? is a charming story, and Yakusho’s portrayal of the shy businessman’s gradual blossoming is wonderful.

The film opens with a scene that feels almost superfluous; in a ballroom in the Blackpool Tower, as elderly couples dance, a voiceover explains that in Japan, ballroom dancing is regarded with suspicion. Married couples don’t even walk about arm-in-arm, and to dance in public, even with your spouse, would be beyond embarrassing. Nonetheless, we are told, Japanese people have a fascination with dance…

Along with the title, borrowed from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I – a musical about western culture being taken east – this opening makes it clear to a non-Japanese audience that this is a film about escaping from the weight of cultural expectations. Nonetheless, the sweet whimsical tone of the film ensures that it treats its themes lightly.

Shohei’s journey inevitable leads him to a competition, but the best thing about Shall We Dance? is that it’s about dance as joy, as escaping your limitations. Watching Shohei’s journey as he goes from stiff and hesitant to the final dance scene is heartwarming, feelgood stuff, as sweet and romantic as watching Deborah Kerr dance with Yul Brynner. Yasmeen Khan

Can’t Stop The Music (Nancy Walker, 1980)

Now here’s a coincidence, I did not know that Cruising and Nancy Walker’s atrocious faux-biography of the Village People, Can’t Stop The Music, we’re both released in the same year. And I certainly didn’t know that Cruising lost out on both the ‘Worst Picture’ and ‘Worst Screenplay’ awards to it at the Razzies in ’81, but it certainly seems appropriate, as, looked at a certain way, the films provide fascinating mirror images of each other and their represented city, New York. Where Cruising‘s dank over-seriousness occasionally pushes it to the brink of hilarity, Can’t Stop The Music‘s gut puncturingly desperate attempts at comedy are forced and unbearable; where Cruising is overt about rough gay sex and power play, Can’t Stop… is coyly sexless, which is prudish to the point of offensiveness given its subject matter; where Cruising presents the night-time world of S&M and leather bars, Can’t Stop… is a garishly lit, toppling wedding cake of weak song and dance scenes punctuated by excruciating acting. And where Cruising has Pacino’s magnetic poppers-powered fist pumping, Can’t Stop… has… well, it has the Worlds Most Average Actor on roller skates.

But, oh, what a joyful scene. The kind of scene that lights up the whole world with its simple, sweet natured stupidity and carelessness. Steve Guttenberg’s Jack Morell, fresh from quitting his square-ass job at a square-ass record store, takes to the streets to celebrate his new freedom by rollerskating hectically about in a manner that the script undoubtedly specified as ‘carefree’ but which comes across more as ‘reckless to the point of making it look as if Mr. Guttenberg has a death wish’. But, by God, he’s a happy man. Look at him, grinning like a post-blowjob fitness instructor and ‘hell yeah’-ing to absolutely no one as he rolls through New York’s magnificent streets. Occasionally the camera will split and triple screen itself in order to show you just how ecstatically demented Guttenberg is from various angles, like some kind of Lovecraftian joy-shoggoth, incomprehensible to the lowly geometries of men.

“New York!” honks David London “We’re skating down broadway!” And, suddenly, we are! Guttenberg breaking his glide only to dance at some uncomprehending bin men and grin at lanes full of traffic as he nimbly pilots his way through them. Normally under these circumstances the appearance of the glittering name of co-star June Havoc would seem less like an announcement of talent and more like a dire warning, but such is Guttenberg’s ruthless viva-la-vida-ism that no one gets out of their car and lands him a skull splitting blow with a tire iron. Wow! Did Guttenberg’s relentless beaming just cause a shop window full of glamorously attired dummies to spring to life? It did! Is he shocked by this sorcery? Not a bit of it! This is New York, man!

By the time we reach the park all semblance of this film being about an actual city goes out of the window; this is New York as a super tolerant Narnia, a do-as-you-please world of unicycling basketball players, comedy randy grannies and people wind surfing down the street in eye-bogglingly skimpy shorts. It’s insanely uplifting, a massive beam of sunshine in tribute to one of the greatest cities on earth. The New York of this scene is the polar opposite of Friedkin’s grimy metropolis, indeed it is a fabulous place and I would very much like to live there. However, I should point out that if that Steve Guttenberg tries getting a backy off my bicycle I will f*cking brain him. Mat Colegate

Badlands (Terrence Malick, 1973)

He was a James Dean replicant with no conception of earthly morality, she a hypnotically blank living ragdoll. Both were byproducts of a gorgeously wind-eroded pop Americana that only ever existed in Terence Malick’s mind.

If it’s virtually impossible to choose the most spellbinding moments shared onscreen between Martin Sheen’s Kit and Cissy Spacek’s Holly, the two dance scenes in Malick’s’ 1973 lovers-on-the-run fairytale Badlands perhaps best encapsulate the film’s inimitably mesmerizing moods. The first might pass for a human mating ritual as glimpsed by an alien consciousness; Kit and Holly’s courtship boogie makes for such exotically strange fauna that the soundtrack’s nearly forgotten R&B classic ‘Love Is Strange’ could be swapped out, and a David Attenborough voiceover subbed in. The second, a headlight-washed slow dance set to Nat King Cole’s ‘A Blossom Fell,’ perfectly expresses the vast, desolate dreaminess of the Great Plains. It would take endless viewings to fully unravel the mysteries of Badlands‘ peculiar tone, but one encounter with these images is all that’s needed to permanently commit them to memory. Michael Wojtas

Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006)

I’m not sure if it’s strictly matching the canon to say so, but I think Inland Empire is David Lynch’s finest film. As his most well-realised and most viscerally affecting examination of the themes and atmospheres he was reaching towards in its predecessors Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive – the fragility of memory, paranoia, psychosis, and their tangled relationship with acting and filmmaking – it’s certainly the one I revisit most regularly. Its free-flowing, disorienting narrative spills outwards from a series of premises, centred (err, I think) around the question of: what if an actor, without realising it, were to become stuck within the role they’re playing? You swiftly become as lost within the film’s Russian Doll-like stack of identities-within-identities as Inland Empire‘s protagonist, leading to several moments of subtle yet pervasive horror that rank among the most unsettling of Lynch’s career.

So, after three hours of claustrophobic twists and turns, murkily lit rooms, comedic interludes and abrupt unexplained jumps in time and place, the film’s closing credits offer one final surprise. The cast – both those we’ve spent the film with and the motley cast of shadow characters their dialogue has conjured up throughout – gather in a wood-panelled room to dance to Nina Simone’s Sinnerman. After the paranoid, unstable situations we’ve encountered them in earlier, the prevailing mood turns to one of joy and release, with all that pent up tension released in one final burst of energy. As with the best of Lynch’s work it’s strikingly moving despite being almost unfathomably strange, even outright silly, but after the uncertainty that came before, it’s as refreshing as a deep breath of cool, fresh air. Rory Gibb

The Man Without A Past (Aki Kaurismäki, 2002)

What do you have when you have nothing? Kaurismäki’s Finland trilogy, of which this is the second instalment, is about unemployment, homelessness, being forgotten by society. Markku Peltola plays M, a man who finds himself literally without a past when a gang of thieves beats him up and leaves him for dead in a Helsinki park. From his hospital bed, he’s born anew, with his face swathed in bandages – literally an invisible man.

As Irma, M’s Salvation Army love interest (fellow Kaurismäki regular, the wonderful Kati Outinen) says, “God’s mercy reigns in heaven, but here on earth, one must help oneself.” Nonetheless, M finds company and assistance amongst Helsinki’s poor and homeless population, and begins to build a new life out of nothing. The comedy is typical of Kaurismäki, pitch-black and lyrical. But the sun shines in this bright version of Helsinki, and music punctuates people’s days here as it does everywhere. A man sometimes plays the accordion, a Salvation Army band entertains the soup queue, and a salvaged jukebox, hooked up to stolen electricity, is the first thing M brings back to his new home (a container vacated when the last occupant froze to death, rented out at an extortionate price by a corrupt security guard).

Music brings meaning to a literally meaningless life. After M talks to the Salvation Army band about rock music, they decide to embrace worldly music, and play “a song about the human heart” for Midsummer, a “pagan feast”. When the homeless people they’re feeding begin dancing it’s like an affirmation – music belongs to everyone, everyone can respond to it, and everyone can express their response – even those who don’t even have a name. It’s also a reminder that you don’t have to be competent, physically fit or dressed a certain way to find pleasure in dancing, and it’s a demonstration of togetherness and camaraderie that will be brilliantly echoed at the end of the film. Yasmeen Khan

Stroszek (Werner Herzog, 1977)

Werner Herzog’s films often feature characters unable to escape, whether it’s destiny, history, geography, or themselves. Stroszek, the 1977 film that the German director wrote especially for the wonderful, naturalistic actor Bruno S., makes this explicit in a terrific closing scene. After stealing a handful of dollars and a frozen turkey from the grocery store of a everywhere America mountain town, Bruno wanders into an old-fashioned games arcade, and sets the entertainment in motion – a rabbit in a firetruck, and a chicken that pecks a piano starting a rolling all-American tune, scratching and flicking its legs on a circular dancefloor as a shrill voice calls "woah heeeee ahhh hheeeee".

Herzog has said that the chickens are a metaphor for "something", and perhaps his vague explanation is because this is that rarest of things: a metaphor that’s obvious without being crass. The chicken, condemned to dance forever a the tinkle of a quarter, represents the failure of the American Dream as endured by Bruno, the appalling shrieking music its soundtrack. The radio crackles at the end of the scene: "We’ve got a truck on fire, can’t find the switch to turn the ski lift off, and can’t stop the dancing chicken. Send an electrician". Luke Turner

For more information on the BFI’s ‘Gotta Dance! Gotta Dance!’ season go here: https://whatson.bfi.org.uk/Online/default.asp?BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::permalink=gottadance