I do not know how many moments feature on this list. I know roughly the number of films, but I do not know which one is objectively the best. We could have tried to order them, to celebrate one film a little more than the others, to crown a winner of the race. But I didn’t really want to do that this year.

I am not going to explain how ludicrous this year was, or try to make sense of it. All I can do is welcome you to what I hope is one of the final lists you’ll read this year, in which esteemed Quietus contributors write a tribute to their favourite moments in movies they have seen this year. I don’t know if they consider the film they’ve chosen to be their favourite of the whole year. I was interested in the details, the frame, the experience, the design, the line reading or whatever tiny thing they found that brought them a flicker of joy, of hope in 2020.

Some films are featured twice, and there’s probably a little more than a round number here. I would apologise for this, but I think we all deserve a little generosity 10 months into whatever has happened this year, don’t we? I hope you enjoy remembering these moments which might have struck you too, or find feelings that resonate and could make your holiday season a little lighter. So many of these choices reminded me of the reasons I’ve been so thankful for cinema this year, even though the format has changed beyond compare.

I don’t know what’s going to happen next year, nor where my favourite moments of 2021 might take place. But if 2020 has taught me anything, it’s that there will always, always be magic to be found in the movies. Wherever and however we might be watching them.

– Ella Kemp, Film Editor

#Alive, Cho Il-hyung

Joon-woo (Yoo Ah-in) is rifling through the bedroom of one of his neighbours when his eyes suddenly light up. Some time ago, a zombie virus threw his city into turmoil and drove him back into his apartment, barricading the door with an empty refrigerator. But now that emptiness has become a problem, forcing him to clamber out of his safe space in search of supplies. He anxiously fills his bag with all kinds of useful things until one particular treasure stops him dead in his tracks: a tiny pot of Nutella.

Great acting can bring a person’s whole inner world to the surface in a single wordless moment, and watching Yoo Ah-in burst into ecstatic celebration at the sight of this minute container of hazelnut paste is one of them. We see the stress, frustration, fear and exhaustion the pandemic piled upon him, and we watch it all slide right off. It’s something so trivial, something which was so everyday right up until the virus turned “everyday” into something else entirely. Something so seemingly meaningless, meaning everything to him.

Because when the whole world seems to have gone to hell, the smallest glimpse of something familiar and good can be a balm for your soul. – Ross McIndoe

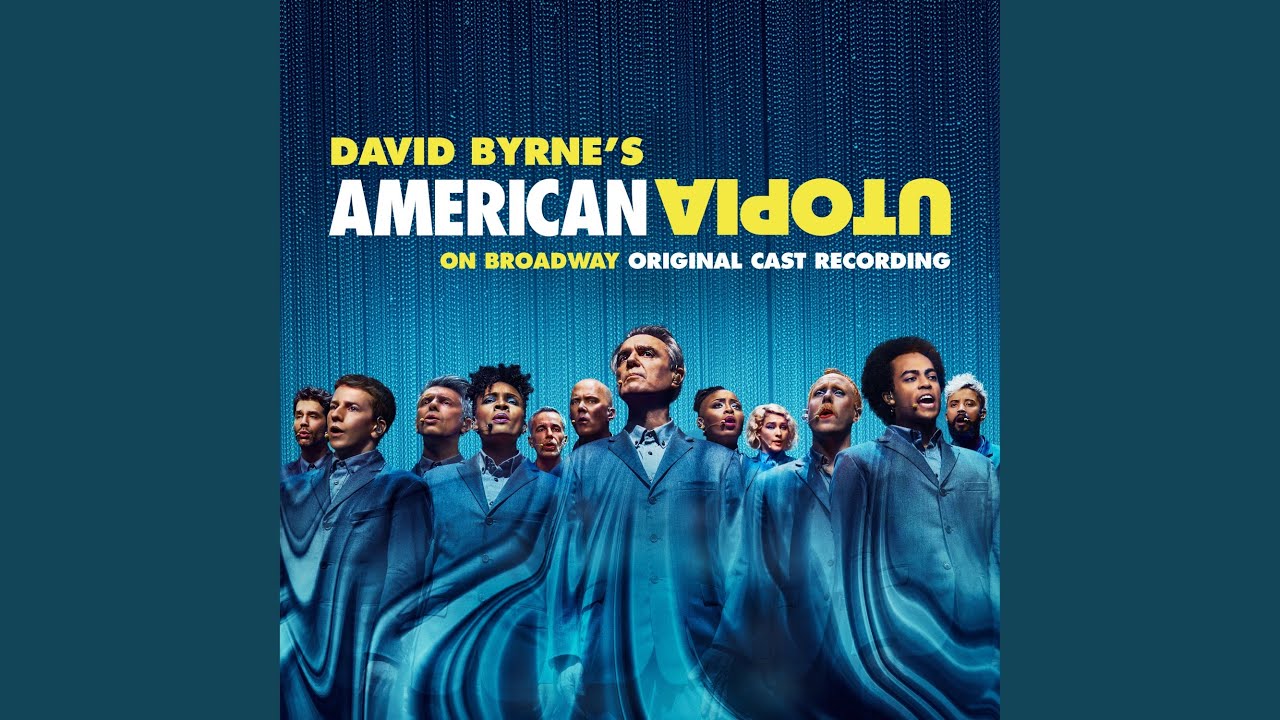

David Byrne’s American Utopia, Spike Lee

When David Byrne starts singing ‘I Know Sometimes a Man is Wrong/Don’t Worry About the Government’, a ray of light hits his head as if something angelic is about to happen. The medley comes right after Byrne’s first monologue, and represents a perfect example of what American Utopia is as both a film and a stage show. The song, from 1989’s Rei Momo, is a stark example of Byrne’s weirdness from his solo career. For the American Utopia performance, Byrne pairs it with a Talking Heads ’77 fan favourite, making the mashup start with an oddball performance of a solo song he seems to love and end with a crowdpleasing classic for the audience. One for him, one for them.

What makes ‘I Know Sometimes a Man is Wrong’ so enthralling is Byrne’s raw emotion. The eccentricity and anxiety of his time in Talking Heads, the eccentricity and anxiety of David Byrne’s persona is well documented – so with that context, “I know sometimes a man is wrong, I’ll be wrong until you’re next to me” feels deeply human. In comparison to American Utopia’s most show stopping numbers, this medley might not feel like much. But there’s a charm to this one that hasn’t left me since I first watched it. – Ethan Gordon

David Byrne’s American Utopia, Spike Lee

If Jonathan Demme’s 1984 concert classic Stop Making Sense was an adrenaline-fuelled manifestation of art for art’s sake, the Spike Lee-directed American Utopia arrived this year with a more grounded message: when will things start making sense again? In featuring a get-out-the-vote plea and a timely tribute to Black victims of police brutality, Lee and David Byrne dropped many of the absurd theatre influences which made Stop Making Sense so iconic in favour of a concert experience expressly suited to our times.

The focus may be different, but American Utopia is very nearly as potent. After a cerebral beginning, Byrne’s dance collaboration ‘Lazy’ really takes things up a notch. When bassist Bobby Wooten III arrives on stage plucking at a chrome, sci-fi-looking guitar, the tempo – and our pulses – quicken and never quite come back down until the credits roll. The moment is equally joyful and silly, the nebulous lyrics of ‘Lazy’ very much in service to an early-2000s dance beat by English DJ duo X-Press 2 which ties it all together. A shot in the arm to Lee’s film as well as to an otherwise dour year, the ‘Lazy’ sequence in American Utopia can’t be overlooked as a winning 2020 moment for cinema. – Adam Solomons

Read the Quietus feature on American Utopia

The Assistant, Kitty Green

There is no flashy monologue or explosive climax at the end of Kitty Green’s The Assistant. Instead, this blistering indictment of toxic office culture is fixed to a low simmer throughout, as it depicts the parade of indignities suffered by Jane, an assistant to a Weinstein-type producer. At the end of the wrenching workday, she sits alone in a small cafe unwrapping the plastic from a sad deli-muffin she will have for dinner. The camera is static watching through the window – she’s on display like one of Hopper’s Nighthawks. Jane calls her father to wish him a happy birthday, but when his warm and aloof voice asks about work, she struggles to maintain her composure.

The final indignity here, after spending the day stifling emotions, is that her feelings of exhaustion, frustration, loneliness and guilt must remain an unspoken torment even after clocking out. In a year defined by tragedy and distance from our loved ones, this piercing moment speaks vividly to the way trauma isolates us from the people we need most. I keep thinking back to the silent restraint of Julia Garner’s expressive eyes and pained smile as she fumbles for empty reassurances during the call – a torturous and unforgettable heartbreak, hiding in plain sight. – Igor Fishman

Babyteeth, Shannon Murphy

Terminally ill teen Milla has begun her chemo treatment, and she’s also fallen in love with Moses, a delinquent boy much older than her. Faced with the inescapability of her own death, Moses’s disordered, definitively problematic arrival in Milla’s life acts as the catalyst to a final burst of romance and joie de vivre that thrusts Milla’s last days into the throes of passion, pain, and utter radiance. During a session with her violin instructor, Gidon, where the two engage in playful, insulting banter to one another over her inadequate ability to perform, Milla coyly reveals that she’s got a boyfriend. Gidon throws a record on to reflect Milla’s infatuation. Milla begins to dance.

The infectious violin melodies of Sudan Archives’ ‘Come Meh Way’ guide Milla as she sways and shakes and swings her arms, in a scene which acts as a hallmark of her newfound happiness, the camera holding intimately on Milla’s movements. Milla’s mother, Anna, eventually walks into the room to see her daughter oscillating to the beat, her motions erratic and unfettered in their manifestation of Milla’s joy. Anna shares a warm smile with Gidon. Moments before, the camera had pivoted to the otherwise unchanged outside world, of the reality that still exists beyond apartment walls, that waits for Milla when the song is over. But in Gidon’s studio, there is only Milla. – Brianna Zigler

Bacurau, Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles

The gory rewards of this slow-burn genre-bender do not come quickly. Evoking the worst of colonialist arrogance and contemporary America’s gun-nut atrocities, Bacurau sees a Brazilian village beset by bloodthirsty western trophy hunters who shoot people for points using “vintage” US weapons. The film works hard to characterise the village’s tight community of doctors, sex workers, teachers and gangsters, all of whom are treated equally. Already plagued by political corruption and reeling from the death of their matriarch, their collective vulnerabilities ensure our empathy, so that each death feels like a gut-shot. As the foreigners finally infiltrate Bacurau to wipe out its residents, there comes a turning point.

When the Museu Historico de Bacurau invites the killers to inspect the history they have until this point ignored, they learn what they might have known already had they not been so conceited: that Bacurau has a history of violent rebellion. The village’s own “vintage” weapons – which include Colts and Winchesters, archetypal firearms from that most American of cultural products, the western – are conspicuously missing. Still, they don’t care. “Heads up, guys,” says Terry, barely suppressing a laugh. “The locals might be armed.” Shortly after, Bacurau’s gender-fucking bandit talisman Lunga emerges from the shadows. It’s an electric moment loaded with history, as Bacurau points the Western genre back at itself and prepares to pull the trigger. – Sean McGeady

Read the Quietus feature on Bacurau

A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Marielle Heller

It’s rare for cinema to pause. We’re told it’s supposedly both illogical and antithetical to drama to loosen an audience’s grip on the narrative and reveal the artifice at play. It’s a technique almost exclusively reserved for Slow Cinema, or contemplative cinema, and filmmakers like Béla Tarr or Tsai Ming-Liang. Yet, it couldn’t feel more at home in Marielle Heller’s drama about the relationship between television icon Fred Rogers and journalist Lloyd Vogel.

The moment arrives in a scene where Lloyd asks Fred how he can love broken people like himself. Fred refutes the idea that anyone is broken, suggesting that Lloyd’s convictions are positive products of his experiences with the people in his life. It’s at this moment that Fred asks Lloyd to sit in silence for a minute, reflecting on the people who loved him into being. Heller lets this minute play out in real time, asking the audience to accompany Lloyd and Fred. I remember seeing this at a cinema in Brighton and staring at the bottom right corner of the screen. Once it ended, I felt a wave of gratitude. It was a powerful and startling moment which in the wrong hands could feel forced. Yet, in the hands of Marielle Heller, Tom Hanks and Fred Rogers, it felt essential. – James Maitre

Bill & Ted Face the Music, Dean Parisot

Many of my favourite cinema experiences of 2020 – seeing Autumn de Wilde’s candy-coloured Emma. with a giddy packed audience, or Leigh Whannell’s airtight The Invisible Man with a more on-edge one – happened so early in this painfully protracted year as to feel like they occurred in another decade. Since cinemas first closed back in March, 2020 has brought escalating societal fragmentation and tension, freak weather, whatever the hell QAnon is and, because you can never emphasise it enough, a goddamn pandemic – and yet somehow in the middle of it all there landed, incongruously, like a time-travelling phone booth dropping into a California suburb 29 years after its last appearance, Bill & Ted Face the Music.

This was a film that found amusement in naming a killer robot Dennis Caleb McCoy, and in asking 50-something professionals Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter to behave like clueless teenagers for 91 disposable minutes. It feels almost indecent that such a good-natured, proudly uncomplicated piece of entertainment even got released in 2020, and that it wasn’t just saved for an unspecified future date in which we were actually deserving of it. There were deeper and better-crafted films in 2020, but I’m thankful to this one for getting me back in a cinema and allowing me to momentarily switch off from this most un-switch-off-able year. – Brogan Morris

End of the Century, Lucio Castro

In retrospect, End of the Century is the perfect celluloid representation of the hobbies we adopted during 2020: meandering laps around the local park to ease the existential angst, long periods of self-indulgent rumination, and getting blasted on cheap red in your living room. The most gloriously realised life-imitating-2020 sequence in Lucio Castro’s film, however, is his depiction of the late-night living room dance.

After Javi suggests he be Ocho’s tour guide for the day, they decide to return to Javi’s flat for a night of tequila and bad dancing. With an ecstatic needle drop, Castro’s film shifts on its axis — in a sudden shudder of excitement and uncertainty, the camera woozily glides alongside the pair as their delicately intoxicated dancing becomes increasingly seductive. Filmed in one unbroken take, the sequence feels like the inverse of a Robyn sad-banger. For Ocho and Javi, both of whom have girlfriends, the sudden drunk realisation of each other’s sexual identity and mutual attraction sends a jolt of energy through Castro’s entire film and an apt reminder of the modest utopias we’ve learned to build. – Jay Crosbie

Host, Rob Savage

2020 has been a year of mandatory creativity and no film exemplifies that more than Rob’s Savage second-screen horror film, Host, where a group of friends hold a seance that goes horribly wrong. The entire film was shot remotely over Zoom, which makes its scares all the more impressive. Savage’s use of Zoom features such as background images and face filters make the piece of technology that has kept us connected to the world into something with horrifying potential.

The best moment of this film, and of 2020, involves a floating mask in character Emma’s living room. The mask, a tribute to the cult classic Alice Sweet Alice, floats in mid air, at first appearing to be a glitch in the video. A long static shot builds and builds suspense as Emma slowly moves toward the digital image, only visible on her laptop screen. When she finally approaches the mask, it turns towards her, indicating that there is in fact something sinister here. Not only is this an incredibly effective jump scare that never fails, but it creates fear in the most relevant way possible. – Mary Beth McAndrews

Hubie Halloween, Steven Brill

In a year where going to the cinema, being with friends, and just about everything else related to normal life became more infrequent than ever, there was one constant that was able to bring about a sense of normalcy. His name is Adam Sandler. Long a fan of his particular brand of asinine antics, the one good thing to come from months locked away from the world with too much time to watch films was the ability to finally commit to my lofty goal of watching every single one of his film appearances. So when my personal quest was coming to its end and the greatest comedian of our times decided to release another film, Hubie Halloween, which featured him playing almost the exact same role we’ve seen dozens of times before with a plot and comedic beats to match, I was overjoyed.

Settling down to watch it with a pumpkin-flavoured ale to accentuate the spirit of the season, I experienced a sense of normalcy never found elsewhere during this pandemic. I could’ve been a young kid watching Happy Gilmore or Click for the first time again as I delighted in seeing Hubie react to a fright in the same manner as my father. For one hour and 42 minutes, the world was at peace and I discovered the joys of Sandler all over again. No film this year could compete. – Henry Baime

I Was At Home, But…, Angela Shanelec

Angela Schanelec’s I Was At Home, But… might just be the German’s director most refined example of the formal rigour her films possess, and the way in which she allows for shafts of light to poke through said rigour, in the form of humour, poignancy, a well-timed needle drop, and more. The film follows Astrid (Marin Eggert), a middle-aged mother of two experiencing something of a subdued and prolonged crisis two years after her husband’s death, an event she’s reminded of after her young son returns home after being disappeared for a week.

Astrid is irresolute to verbalize all that she’s feeling, save for one bravura, 10-minute take, where her vacillating emotional state spills over into a chance encounter with a presumed experimental filmmaker (played by Dane Komljen) she’s acquainted with. His most recent film houses a scene where actors and dancers meet with the terminally ill patients of a hospital, a blend of fact and fiction that Astrid reasonably perceives as little more than a blown-out distortion of the truth. Komljen’s face registers a kind of flummoxed politeness as Astrid rattles off one cogent point after another, and her takedown of what sounds to be a highfalutin film is more affecting than any straightforward proclamation of grief could ever be. – Patrick Preziosi

Lovers Rock, Steve McQueen

Ladbroke Grove, early 80s. In the early stages of a house party, the women dominate the floor to Chic, the men hang back, smoking spliffs. The aunties sell goat curry. Tomorrow, there’s church. Sex tonight is restricted to fervid grinding and sweet, sweet talking. The Caribbean mating game unfurls in a welter of disco and reggae.

A deadly golden glow suffuses McQueen’s Lovers Rock, the second film of his Small Axe series. A single night immerses us in the liberation of one’s animal, island self. As a rural raver, I practise home clubbing with my lover, quasi-religiously. But in this year of turmoil, with city clubs shut down, we loved plunging into McQueen’s flushed faces, elbows and another household’s throbbing sound system. When Chic’s slick guitar is dropped for ‘Kung-Fu Fighting’ and everyone – magnificent girlfriends, creepy guys, a happy couple who rush into the room – knows what to do, McQueen foreshadows the violence and solidarity of our present time. The silly Orientalist riff boosts the dancers’ faux fight poses into innocent belief in our super powers. Outside, the world is racist and shitty; but here in this lamplit room, funky bass, satin skirts and a heartfelt hook will prevail. – Soma Ghosh

Lovers Rock, Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen has always been adept at exploiting time in his films, deploying a special understanding of the unique properties of cinema for manipulating time, and space. In Lovers Rock he does this in exhilarating ways that showcase Black people, to borrow a phrase from Jenna Wortham, ‘fully embodied and carefree’. In two sequences, thematically and emotionally connected, he gives cinematic time and space over to bodies in slow and dizzying motion and lets those bodies, and the minds and souls that inhabit them, simply be.

At a Blues Party in 1970s London a DJ plays the Lovers Rock anthem Silly Games by Janet Kay, and the gathered throng create a compelling echo in the form of an a cappella coda that essentially encompasses the whole song over, eyes closed, bodies slightly swaying, rooted but moved by a gentle breeze. Everyone lost, in safety. Not long after, the music shifts to the fierce, ethereal, propulsive Dub of The Revolutionaries’ Kunte Kinte Dub. The movement is harder and faster, and the screams for the track to be rewound as ear-splitting as the sound system speakers. Everyone united, in safety. – Neil Fox

Mangrove, Steve McQueen

The Small Axe series offers the best in popular socially conscious cinema in five feature-length instalments on Black activism, racism, and the Black Carribean diaspora in Great Britain in the late twentieth century. Chronologically the first of those instalments is Mangrove, the true story of a galvanizing Caribbean restaurant in London’s Notting Hill and the black activists who patronized The Mangrove. The Mangrove Nine, that included the activists, Black Panther Party members, and Mangrove’s owner Frank Crichlow, are put in a show trial after a police raid by the London Metropolitan Police. McQueen crucially links the issues of gentrification and policing as collaborative against Black-owned spaces with racism ultimately being the reason The Mangrove was targeted rather than any illegal activity.

The trial, which involved some members representing themselves in court, is locked into having the defendants fight in an unfair, Kafka-esque system while the city around them goes through rapid change. An electrifying montage is underscored by the futuristic ska song by the band Symarip called ‘Skinhead Moonstomp’, pulsating on screen as archive photos present the escalating white-focused urbanization in the Notting Hill neighbourhood while The Mangrove Nine work on their court tactics. The bigger picture is not lost by McQueen that this trial is in the backdrop of a rapidly changing world that threatens to leave the Black Caribbean population behind. – Caden Mark Gardner

Nomadland, Chloé Zhao

Blurring the lines between documentary and narrative fiction, Chloé Zhao has firmly cemented herself as one of the finest filmmakers working today. A signature of hers is working with non-professional actors who inhabit the world of her films, which brings a sense of authenticity and grounds their deeply emotional and sometimes spiritual stories. With Nomadland, Zhao takes the writing, editing and directing credits as she implements her vision of Fern’s (Frances McDormand) journey, telling the story of the real-life nomads along the way in a heartfelt, devastating way.

There is one moment of editing which is particularly satisfying, perfectly demonstrating how damn good Zhao is. Fern is walking along the coast with violent waves crashing against the shore, against Ludovico Einaudi’s soundtrack building to a crescendo. The wide shot implies Fern is overcome by waves of grief, and as Einaudi’s track reaches its peak we cut suddenly to Fern slamming her van door shut. It perfectly encapsulates how Zhao is able to seamlessly flit between big-scale, cinematic moments with lofty themes and ideas and the most intimate, close-up human moments. Ideas that are often universally relatable, planting her feet firmly on the ground. – Daniel Broadley

Read the Quietus feature on Nomadland

Palm Springs, Max Barbakow

“Let’s waste some time,” Sarah agrees to indulge Nyles in the time-loop shenanigans as a way to stall the monotony of reliving the same day on repeat. Palm Springs was met with applause when it debuted at Sundance in January, but little did the creative team know how much it would resonate when it landed on Hulu and drive-in screens in July.

One particular highpoint is the joyful montage of outlandish antics to fill an endless day, which culminates in a standout (and well-practiced) dance routine that ticks those off-kilter Ex Machina boxes. Strutting into the bar they have been frequenting wearing matching Americana outfits, the stunned regular patrons have no idea they have seen this couple before. Patrick Cowley’s ‘Megatron Man’ is reprised from Nyles’ earlier bold wedding dancefloor moves, which gives double the choreographed fun. This scene hit even harder in the cathartic department as the pair spin around flipping the bird, mixing DGAF vibes with a burst of serotonin that was definitely needed by the time the summer rolled around. – Emma Fraser

Saint Frances, Alex Thompson

Bridget is having a minor breakdown. She’ll be fine, she knows this, but she can’t stop bleeding and has just burst into tears. Kelly O’Sullivan writes and stars in Saint Frances, directed by her partner Alex Thompson to tell the story of a 30something woman grappling with the aftermath of an abortion while also starting a new job as a nanny.

The film is teeming with dialogue that is witty, incisive and tender in turn, but it’s when O’Sullivan’s Bridget is overwhelmed opposite the two mothers of Frances, the kid she’s taking care of, that she says "I don’t know why I’m crying, I’m an agnostic feminist."

I’ve been thinking about this line all year. 2020, for me, has been defined by so many moments of very mundane frustration, emotional outbursts that have no rhyme or reason and ultimately completely vanish in a few hours. I’ve cried a lot, my beliefs and values have felt a little shaky. But to put a name on it, to actually verbalise and process the ridiculous but still valid moment of catharsis where everything becomes a mess but it’s the first step towards making sense of it? It might not have changed the world, but Saint Frances felt like some kind of salvation. – Ella Kemp

Undine, Christian Petzold

It’s deceiving to think of fairytales as an escape from reality. No, they speak volumes about the real experience of thresholds, growing, and learning to acquire new social functions.

Christian Petzold’s Undine, a fairytale bathed in realism, washed over me as part of the audience, no less than 10 months ago. Particularly realistic about its Berlin setting, the film took me by the hand and traversed some well-known spots: the Hauptbahnhof, the bridge over the Spree behind the Bundestag, provided a window view of nighttime Alex (the Berliner pet name for Alexanderplatz). Undine cultivated a loving look of its city by repetitions, making its protagonists (fiery duo Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski) tread the same paths again and again, with subtle differences – just enough for me to discover more and more of the same love each time.

Berlin is the one foreign city that I’ve shared with all my partners, and I admit to all the skepticism that this time around would not be a mere repetition of a life already lived. But the thing about Undine is that, by being Petzold’s one possible love story, it swooshes its audience with enchantment without glamourising love at all. Berlin was built on marshes, and muddy waters mark its tough beginnings. Not unlike my relationship’s topography (be it city or love), it harboured the unexpected, the story that would save my 2020. – Savina Petkova

The Vast of Night, Andrew Patterson

It’s Friday night in Cayuga, New Mexico, and something is out there lurking – traceable only by the gurgling, droning noises local high-schoolers Fay and Everett pick up on the radio and phone lines at their late night jobs while the rest of the town is congregated for the local basketball game.

The question of what is it? is the relatively simple premise of director Andrew Patterson’s sci-fi debut The Vast of Night, but the suspense, terror, and sheer curiosity Patterson is able to bring out is due to the masterful use of sound. The sound design and mixing teams harness the hollow expanse of the small desert town, making even the smallest warble or zap alive with all the possibility in the world – an absolutely masterful use of (maybe alien?) noise. – Madeleine Seidel

Read the Quietus feature on the best film scores of the year

Vitalina Varela, Pedro Costa

In October, I headed to Film Fest Ghent in the laughable disguise of a "young critic". Invited by the Belgian publication photogenie, I indulged in my fledgling status, walking with a hop and a flutter, wings and tail slightly too short, straying not too far from the nest. This was the first time I had been abroad during the pandemic, and my sensitivity to emerging brightness was more acute than usual. Apocalypse and artifice, in tandem, seemed to pervade the city, as masks lined the waterway to the main festival theatre. Outside appeared stark and sepia, so the cinema, in obvious contrast, offered discomforting darkness.

Watching Vitalina Varela heightened this exalted sensorium. Pedro Costa’s most recent film is about, and named after, a woman who arrives in Lisbon from Cape Verde, looking for her estranged husband. Its images are largely founded on the interplay of light and not-light, and its stylized theatricality elicits a perverse appreciation of the real, one impossible to replicate in common sense experience. Through its studied pictorial textures and calibrated narrative rhythms, Costa’s film locates the gap that cinematic art expands, the line of inclusion and exclusion – more typically known as the insoluble problem of depiction. – Joseph Owen

Wolfwalkers, Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart

The latest feature from the folks at Cartoon Saloon is an enrapturing coming-of-age fantasy as well as fierce environmentalist, anti-colonialist screed, revising the history of the British Isles (and deservedly humiliating a cartoon Oliver Cromwell) in its battle between ‘civilisation’ and the wild. As with the studio’s other features, the craft of the film is impeccable, lifting and adapting the styles of their finest contemporaries – Studio Ghibli being an oft-cited influence – and mixing them with their own back of tricks, and an art style that smartly contrasts the flowing lines of the wild with the rigid, angular woodcut style of the town.

Most beautiful of all is a sequence in which protagonist Robyn, in the body of a wolf, runs with a pack for the first time, experiencing the world through their eyes (and nose). Those sensations are depicted through the film’s delightful ‘wolf-vision’, which melts away the natural, earthy tones of the rest of the world for a new contrast of grey and multi-coloured lights resembling smells and sounds. The sequence moves with the grace of golden-age Disney, but with a little more modern flair – all of the different elements Moore and Stewart and co. played with in the rest of the film coming together in spectacular fashion. It’s some of the finest Western animation in years. – Kambole Campbell