When Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart were carrying out research for their animated environmental opus Wolfwalkers, they came across an unusual anecdote about their hometown in Kilkenny, Ireland. “I read about witch trials in the States,” Tomm says, “and anybody from Kilkenny was immediately under suspicion.” He explains an old myth about Ossory, a medieval kingdom whose capital was Kilkenny, where it was said that werewolves stalked the land. When it came to the witch trials, then, colonists feared that those from Kilkenny might have the same magical powers. “I just thought, this is too cool not to speak to.”

That deep, impassioned curiosity for Irish history and mythology is the lifeblood behind Wolfwalkers, one of the best animated films of the year. The latest in a string of visually sumptuous, richly-detailed folklore fantasies from studio Cartoon Saloon – also based in Kilkenny – it is a rapturous ode to nature, unruly childhoods, and the joy of accepting who you are. And with the help of a theatrical run and a major release with Apple TV, it could be the defiantly independent, beautifully hand-drawn gem that finally breaks the studio chokehold on the Best Animated Feature Oscar.

These are high expectations, but Wolfwalkers stands on tall shoulders. It’s the third film in a loose trilogy which began with the illuminated manuscripts of The Secret of Kells in 2009 and the selkies of 2014’s Song of the Sea – both Oscar-nominated and critically revered, a breath of fresh air among a glut of homogeneous CG-animated sequels. Wolfwalkers, the first chapter to actually be set in their hometown, transposes the wolves of Ossory legend to the mid-seventeenth century, when Oliver Cromwell led a ruthless English invasion of Ireland. Cromwell – a partial inspiration for the film’s domineering Lord Protector – brutalised not only Ireland’s people, but also its wolves. “He had an idea that all ‘wild’ lands needed to be tamed,” Ross explains, “and he had a bounty on every wolf head that was delivered into his bailiffs.

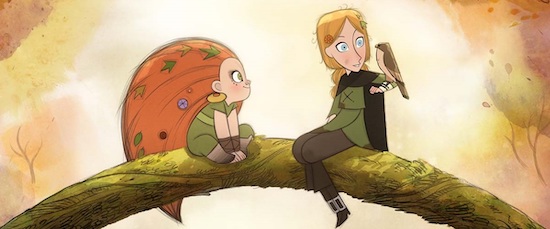

At the start of the film, Robyn, the film’s English protagonist, mimics this colonial mindset. Her father is a hunter, tasked with wiping out the wolf population in the woods around Kilkenny. When she follows him into the forest in secret, however, she meets Mebh, a girl who can shapeshift into a wolf – a wolfwalker – and their relationship changes Robyn’s worldview completely.

What follows is part action-adventure yarn, part anti-colonial fable. What has always made Cartoon Saloon’s work stand out is the subtle intelligence of their politics, imbued without ever pandering or preaching, filled with an earnest respect for children’s autonomy. The film celebrates the childlike mercuriality of a character like Mebh, so sorely lacking in adults like Robyn’s repressed, overprotective father. Where he consigns his instinctually adventurous daughter to the drudgery of scullery work, Mebh is allowed to roam the forest as her own personal playground, joyfully uninhibited, the antithesis of modest Puritan girlhood. She represents everything Robyn has been taught to hate, but which she can’t help but yearn for.

Mebh helps her break free of these gendered expectations – a change embodied most literally when Robyn herself becomes a wolfwalker – and the pair grow to feel a fierce devotion for one another, one which many audiences read as the early murmurings of lesbian romance. Search “wolfwalkers” on Twitter and you’ll find dozens of pieces of fan art by young LGBTQ viewers, thrilled by the prospect of lesbian animated characters after being so starved of representation in their more commercial counterparts.

When I mention this to the pair, Tomm grins: “Look, as two middle-aged blokes, I’m delighted that young women are seeing that in it.” He explains that the gendered aspects of the narrative only emerged after a rewrite: “Originally, Robyn was going to be a little boy. We had a draft or two of the script like that, but something wasn’t working, and whenever we flipped it on its head and made her a little girl, everything made much more sense.”

The film’s LGBTQ undertones emerged as more of a happy accident. “We didn’t do any of that deeply intentionally,” Tomm says. But he emphasises, still, “we had plenty of women working with us on the movie, who spoke to how important that was.” Ross adds that “one of the most important parts of Robyn’s arc is her ‘coming out’ moment, when she decides that she has to tell her father that she’s a wolfwalker.” For Ross, that marks Robyn’s decision to “take her own choices”, to live life for herself rather than her family.

The freedom represented by Robyn’s transformation finds its polar opposite in the authoritarianism of the Lord Protector, and the conflict between these opposing forces eventually boils over in a climactic human vs. wolf battle sequence. Despite this insurrectionary finale, however, Tomm and Ross are measured when discussing the film’s politics. They are wary, and weary, of bitterness and division. Tomm references, for example, the turmoil around the Brexit negotiations and the threat that poses to the Northern Irish peace process.

“We could resurrect all those old hatreds again,” he says. “It’s constantly there and we have to keep it at bay, and at the same time understand where it comes from.” The overriding message of the film, then, is one of unity. Tomm and Ross purposely told the film from the perspective of an English character, who is forced to unlearn the brutality of her own worldview and instead find camaraderie with the very people she is supposed to eliminate.

That camaraderie also informs the film’s awe-inspiring ‘wolf-vision’ sequences in which the camera takes on Robyn’s new lupine point of view, replacing the flattened, blocky aesthetic of the town with rough-hewn, flowing lines and glowing scent trails. “The idea,” Ross says, “is to show the audience how life-changing an episode that is for Robyn.” The technique was developed alongside Dublin animator Eimhin McNamara, who rendered the scenes in a 3D virtual reality model to achieve the POV effect. Each frame was then printed out, and painstakingly re-drawn by hand. “It’s three minutes of the whole movie, but it took the whole production time of the movie to make,” Tomm says.

This unerring commitment to high-quality, hand-drawn artwork is at the core of Cartoon Saloon’s philosophy. Even in the late 2000s, when uncanny valley CGI was at its peak, the pair chose to embrace the care and artistry of traditional animation. Secret of Kells, which marked the studio’s debut – Tomm directing, Ross as art director – is lush with intricate Celtic knots, lavish woodland spirals and dynamic, Genndy Tartakovsky-inspired character designs.

“The animation industry was veering strongly towards realism and trying to be ‘as good as’ live-action,” Tomm says, thinking back to the rise of CG animation in the late ‘90s. “And there’s a dead end to that because, once you’ve achieved it, there isn’t anywhere else to go.” Instead, he sought inspiration from the late Richard Williams – “the animator’s animator”, as Tomm describes him – who directed the animated sequences in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, as well as the mythic unfinished Thief and the Cobbler. Williams’ experimental use of 2D geometry and perspective, combined with what Tomm calls his “virtuoso draughtsmanship”, allowed him to “tell a story in a way that can only happen in drawings”.

Cartoon Saloon’s steadfast belief in the value of hand-drawn animation has spearheaded something of a revival in the style, with spate of recent films – the lyrical Ghibli co-production The Red Turtle, offbeat French indie I Lost My Body, and heartwarming Christmas tale Klaus – seeing surprising amounts of success. “There was actually a bit of competition to get our animators while we were making Wolfwalkers,” Tomm says. “Crazy! We didn’t expect that because we always felt like it was a light that was going out, and now it seems to have been rekindled.”

Part of this revival has been spurred by streaming platforms – I Lost My Body was bought by Netflix following its Cannes premiere, and Klaus was the streamer’s first in-house original animation. Wolfwalkers itself is set to debut on Apple TV in December after a theatrical run, the result of a major deal signed in 2018. “I think the streamers are willing to take more of a gamble than the older studios,” Ross says. “And it shows the general public’s taste is evolving too”. Where Secret of Kells felt like a risky investment in the 2000s, “now you could easily find an audience for a film like that.”

This shift in public interest hasn’t necessarily translated into institutional recognition yet, however. Industry benchmarks like the Academy are notoriously resistant to recognising animation talent outside of the commercial tentpole features. Accordingly, though all three of Cartoon Saloon’s previous features have received Oscar nominations, all three have also lost to films by either Disney or Pixar.

I ask the pair if this frustrates them, but they’re refreshingly uncynical. They speak instead of their pride in the work being done by the Academy’s animation branch, who are responsible for selecting which animated films get nominated. “Even if the broader Academy just votes for Disney,” Tomm says, “our branch always manages to nominate something that we feel, as animators, we want the general public to see more of. I think our branch is important for that reason.”

It is heartening to hear the pair’s positivity – but it is also galvanising. As we discuss this resurgence in hand-drawn animation, Tomm thinks again of Richard Williams, who spent decades struggling against a stifling studio system: “I feel sad that someone like [him] isn’t around to enjoy it”. Ross mentions, too, the support Cartoon Saloon received from the city of Kilkenny in their fledgling days, the kind that has been gutted amidst a pandemic-ravaged arts landscape. It is a reminder that the lavish beauty of a film like Wolfwalkers takes more than just talent: it takes time, funding, public support. Perhaps Wolfwalkers might serve as a plea for such progress to continue – for the next generation of animators to have a chance to tell their stories just as Tomm and Ross have told theirs.

Wolfwalkers is out in UK cinemas on October 26