Here is my story when it comes to Depeche Mode’s concert at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California documented in the film and live album 101: I should have been there but I wasn’t. What was I thinking?

That may seem melodramatic but I had reasons to be annoyed with myself and honestly still have them. It was all due to the fact that in the early part of that year, I got my first CD player. I was a senior in high school then and I was basically starting to explore more back catalogues of artists, or even the sense that such a thing as a back catalogue fully existed. Until then, small exceptions aside, I generally bought new releases. But by then I’d also understood a little more clearly that there were things you didn’t hear on the radio – or more accurately top 40 radio, as Depeche had owned alternative radio for years at that point. I’d taken a break from active listening to that; indeed, I was in my brief classic rock phase as a radio listener.

But Depeche were just so sub-culturally big even in my suburb of a California town – Coronado, on an island in San Diego Bay – that I wanted to know more. It turned out the local record store stocked, among many other things, a lot of Depeche Mode, including all their albums on then-recent domestic CD. So with my hard-earned allowance money I would, every week or every couple weeks, go over and, among other things I was buying at full CD price too, pick up steadily, one after the other, the Depeche Mode discography. (I’ve previously written about Music For The Masses for this site.) Ads I saw posted at the record store talked about some big concert that was happening at the Rose Bowl. However, I hadn’t quite put it together yet to see if anybody was going. It wasn’t a case where I could just simply hop some hours’ drive over myself. At the time I was still working on trying to get my driver’s license, an attempt which in the end never actually panned out. I didn’t consciously know anyone who was going, even though it’s pretty obvious in retrospect that I surely would have done if I had asked.

So I ended up not going. Later that year I start at UCLA, fall of 1988 and on my dorm floor I am surrounded by people who are all wearing these Depeche Mode shirts. They had been to the show, and it seemed like everybody in my dorm period had been too, at least if they were local to start with. I almost didn’t know what to think, it was so omnipresent. Later in 1989 our dorm floor T-shirt, done to celebrate making it through the year while renovation was happening all around us, had as its main design and slogan a riff on the title and artwork of Music For The Masses, itself a nod to many of those concert T-shirt designs. It was hilarious and it was appropriate. But yeah: I was surrounded by the knowledge of this show and by now I am really heavily into the band and I hadn’t gone. What was I thinking?

As it turned out, I more than made up for it. I saw them when they played Dodger Stadium on tour the following year for Violator, when they had become one of the biggest things in the universe, and rightly so. But before then it was first the album and then the video release of 101 where I really got a sense of what I had missed. Before getting into the film – now given a fancy new bonus-laden reissue on Blu-ray along with the album – I’ll just say this is a wonderful, wonderful watch; it was then and it is now. It’s my favourite D. A. Pennebaker film easily; the opening credits rightly name him, longtime partner/collaborator Chris Hegedus and David Dawkins as the three directors and camera operators. It’s a very illuminating film about how a young English electronic band on the road in America works, for lack of a better term. Sometimes the stereotypes are all true with a few Spinal Tap moments, at other times there are unique moments or unusual ones as when Alan Wilder explains how a modern sampler keyboard works.

But the real wild card element is the fact that Dawkins was specifically embedded with winners of a fan contest. They were young fans, high schoolers or maybe just starting at university, in New York getting to see this Rose Bowl show on the opposite coast and instead of just flying them out, that meant taking them over there by tour bus, in partial homage to their then-current remake of "Route 66". Pack them in said bus with not much in the way of total supervision – a little, just enough – then see what happens, then you cut that together with band footage from shows and on the road, and you have what turned out to be a remarkable film.

It’s worth noting at this point that 101, album and film, is a situation where not one but two key artists shaped the image overall. Besides the lingering impact of Pennebaker’s own past work, Anton Corbijn had begun his regular efforts shooting videos with and photographing the band, and his approach is seen throughout the album art and design. His stage design work would come later, so the somewhat spare but effective enough staging for the show is more of a final bow to their 1980s. Yet even that is telling: it echoes the sense in the film that the band have surprised even themselves with their success and haven’t quite settled into it yet, and all without knowing they’ll be bigger yet soon.

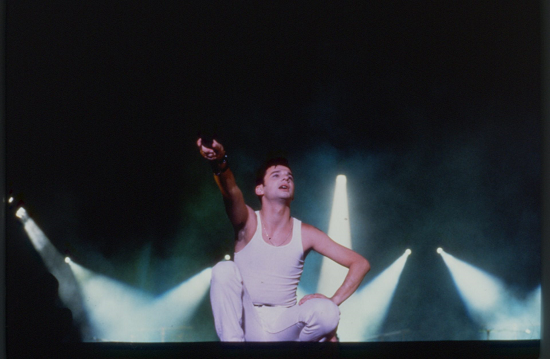

This was something that was still very much sub-cultural for all that we see the various clips of local TV press and interviewers asking the band what’s going on. At the time selling out the Rose Bowl was indeed a very rare event for anything that was not a sports event – they are not yet truly famous, they are still climbing up there there’s a bit of that hunger in their eyes. At the same time there is clear exhaustion, most clearly seen in the sequences where David Gahan is pretty much someone at the end of a particular tether. It’s nowhere near as bad as he would be in the 1990s and not everything is stormclouds, but it’s still unsettling to see.

I preordered my reissue copy almost out of the gate and while I was indulging in some inevitable general nostalgia, this new presentation has also made me think about things that I didn’t clock at the time. They weren’t per se the responsibility of the bands or the documentarians or anybody else yet the issues raised are clearer now than they were before, one a direct result of 101 existing, the other the unplanned counterpart of the film itself. They don’t change or diminish the importance, but they do situate it in a better, more understanding sense.

The first is the most obvious – 101 in essence helped invent the world of reality TV. The question of the documentary form, the access one is or isn’t allowed and which may not show up in the final result, especially if something is an official production, these are axiomatic points that need not be elaborated. The film feels rough around the edges, fly on the wall, because Pennebaker had helped codify that approach already. Comparing that to the now highly polished world of reality TV as we know it, from contests to ‘real life’ drama, may seem a stretch. But the connecting point isn’t the style – it’s the fans. When in the liner notes to the film’s initial appearance on DVD in 2003 Pennebaker wrote "It’s been said that this was the first of the MTV style ‘real world’ stories,” referencing the series that started fairly soon after the film’s release, he might have been either knowing or perhaps disingenuous, but he was absolutely right all the same.

The energetic nature of 101 is one of its greatest strengths, the portrait of a Young Band and Slightly Younger Fans basically having a time together even though they don’t interact all that much, the band more on the grind and sometimes showing it, the kids out for a party. But it’s also the portrait of it being an American fanbase that’s key. More than once I have heard from friends in the UK who are of my age that at that time when 101 came out, they literally could not believe that Depeche Mode of all bands had apparently turned into this huge arena-filling monster over in the US. The band had long continued on from their early eighties breakout but the images and the styles that were most associated with from those days had never quite been shaken, at least up until that point.

In Pennebaker’s work that he had done beforehand, whether it was Original Cast Recording: Company, Monterey Pop, or of course Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars: The Motion Picture or Don’t Look Back, we had cases where the core people were very conscious that they were known and were being filmed. Here those intense young fans that so surprised so many in the UK had no sense of that, not to the full. The idea of just carrying around cheap video cameras – much less even thinking about smartphones capable of recording 4K – was still fairly rare. Handheld film cameras weren’t unusual at least, if again not universal, so 101 is a transitional moment where people are still going out and feeling like they could do whatever without it being fodder for smaller circles or bigger ones the next day. The candid moments feel like a mix of playful posing, silly randomness taking advantage of just having a camera and a cameraperson to interact with and just moments where they unconsciously shoot the shit – it’s always shaped by editors then and now, but there’s really no sense of intentionally whipping up some controversy. As one of the kids said in a bonus feature originally done for the DVD, that meant his own slam on Guns N’Roses after a casual encounter with some affable Albuquerque metalhead bros caused an issue when Axl himself showed up at the LA premiere of the film.

It’s worth separately noting that said metalhead fans are all apparently Latino where the Depeche fans are white – and that leads into the second major issue. When you consider the fans from New York and then also consider the fans who were shot at the Rose Bowl as well as at other shows along the way, they are almost all exclusively white. There are a couple of examples otherwise, but they are only a couple of examples, unnamed. This is a framing of Depeche, however unintentionally, as a band for young white listeners.

It’s worth noting that both the official documentaries since made under the band’s auspices don’t fall into this category. Our Hobby Is Depeche Mode, the 2008 film codirected by Everybody In The Place‘s Jeremy Deller, and Corbijn’s 2019 Spirits In The Forest both show fans from many different backgrounds worldwide. (I especially recommend this essay by one of the fans in the latter film, Liz Dwyer, about her own deep love of the band and part of the reasons for that connection.) We have these newer representations showing that the Depeche Mode fanbase is not quite what it seems to be if you only consider 101. Whether or not this is a conscious corrective, I do not know. Is there anyone at fault necessarily? Was it unconscious at worst, not a knowing fault, but still a fault? Should we ask exactly why it was that a particular dance crowd was focused on in New York? Who attended that club, why was that club picked, what were the decisions going into that involving the radio station who sponsored the night? Ultimately, why is it that we have a crew of young white kids going across the country and being able to enjoy themselves while only having to worry about, as one of their mothers says, ‘dancing too much’?

Indeed, think about it even more and consider the whole trip as privilege demonstrated, a protection via the camera, money and, ultimately, whiteness. There’s various scenes of alcoholic indulgence and mass purchasing, without it being clear what’s legal where and who might not be on the right side of the drinking age. There’s more than a few scenes where people far from the coast interact with the kids and said people will probably strike most people watching now as simply being Trump voter stereotypes. The kids may look a little funny to them – and the scene where some people are amazed by one hairstyle in particular is priceless. It’s fun, however sophomoric at times, it’s seemingly carefree. But if these kids weren’t white? And if there wasn’t a camera, and a different situation entirely. Maybe it would all be exactly the same, but forgive me if I have doubts, both in 1988 America and now.

If this all seems like special pleading, consider: this was not the only notable and now famed documentary from the general time centred ultimately around a group of young New York club denizens obsessed with fashion, dance music, art and wanting to live their best life. Released in 1990, a year after 101, Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning has had no less monumental an impact over time – consider how so much of what is in it has been filtered through the RuPaul’s Drag Race franchise worldwide. But the similarities between the two films have a hard dividing line in the end, with the black and brown drag house members, sex workers and kids on the street, sexualities and genders a range of life, still unable to travel too far, dreams of life free of threats not always answered, opportunities still too limited no matter how hard everyone works. Some died soon after filming, others later but still too soon, with the continuing death grip of AIDS running without containment all a world away from asking for some water to be poured down a crotch on a hot day in the desert. Whatever the angst-filled moments that can surface in 101, nothing is as hauntingly sad and horrifying as the last images of Venus Xtravaganza as the details of her murder are recounted.

Some perspective, of course – it’s not like one should blame the kids of 101 for existing or for the opportunity that they got for happening. The world is often a horror show with possibilities of alleviation, as anyone who lived through that last full decade of the Cold War can tell you, with the roots of future conflicts already well in place. Why not a carefree snapshot in time, however conditional? And a snapshot it is – all the kids in it are now well into their late forties at the youngest, Alan Wilder hasn’t been in the band for a quarter of a century, and Pennebaker has only fairly recently passed on. Nostalgia’s appeal only gets stronger as the distance grows.

Yet even for all the intensity in the songs, the fraught moments where Gahan in particular is reaching a limit on stage, the more mundane concerns about blown equipment and who will pay for ground replacement, 101 bespeaks joy. Every time I watch I wonder once more: what was I thinking by not going? It all builds up to that wonderful performance, excerpted throughout the film (and for the first time via this new reissue, film of every number featured on the album, if not all from the show itself, is included with the bonuses). 101 is a product of its times and whatever it does and doesn’t say and the contexts that can’t be ignored, it is not meant to be nor is pretending to be a full accounting of life and the world. No film can do that no matter how hard some try.

It’s a capturing of a moment thanks to the wonderful inspiration to get Pennebaker involved. I’d say it’s his most successful film about music, period. Of course his earlier films are monumental with iconography and images that last to this day, still being referenced, but instead of cheering audience members always secondary or in the distance 101 captures at least some of them as people, in the same way that we also see various key band staff and band members themselves doing what they need to do to keep their heads about them. Or just doing their jobs – the construction crew building up the massive stage, the security people going over the colour coding of the access badges, the T-shirt sellers and money collectors, the tour bus driver for the kids with his various travails and laughter. Everyone’s in it together, down to the older woman at the Nashville record store selling Martin Gore a Johnny Cash tape and their future manager Jonathan Kessler marvelling at all the money they made while ‘Everything Counts’ gets a dramatic set-closing performance.

101 is self-contained in that you could walk into it not knowing anything about the band, learn a little bit about them and their intense fans, get a sense of what they were like at the time. Something that will never come back has been fixed in this form in a way that is still bubbly, still filmed just so. For all the things that could be done differently or should have been done differently, for all the songs that can be a little on-the-nose lyrically or maybe pseudo-deep rather than truly deep, Depeche still consistently shows throughout via their songs at their best a combination of thoughtful angst, deep emotional worries and pure desire all wrapped up in one place, with killer music.

If there’s a real ‘if only I was there’ moment, I only have to think about when Gahan is singing ‘Never Let Me Down Again’, the lights come up on the audience and we see a sea of people imitating his back-and-forth arm waving as the music hits full symphonic heights. In the DVD commentary from 2003 Gahan likens it to Wagner and he’s not wrong. If there was anybody who took up the banner from Queen after Freddie Mercury’s passing, the evidence is here. It’s a (black) celebration, it’s bizarre, it’s unexpected and it’s wonderful. What was I thinking? What I think now – I should have been there. But at least I’ll always have this.

A deluxe reissue of Depeche Mode’s 101 is out now across a number of physical formats. A digital edition is released on December 14