Hello, lurkers in the dark places and welcome once again to Flickers, The Quietus’s (semi) regular film round up column. There is absolutely nothing that has been left out of this week’s column; it has everything. Absolutely everything. The kind of everything that Everything But The Girl promised, except we have ‘The Girl’ as well. There she is, isn’t she lovely? Everything. Historical dramas, rockumentaries, neon-drenched noir and expressionist masterpieces. Indeed the only thing missing is appalling 80s action movies…

Nope, we have those as well.

Don’t forget to come and join our Facebook group and join in debates on all the scorching topics of the day: Hotshots, or Hotshots Part Deux? Hugh Jackman: Body For Action, Face For Musical Theatre? and Monkeys On Horseback: Are Two Machine Guns Practical? Until you leap into the sarlac pit I shall leave you in the capable hands of the tQ film team. Until next time…

JAKODAAAAAAAA!

Camille Claudel 1915 (dir: Bruno Dumont, In selected cinemas now)

On paper Camille Claudel 1915 would appear to be a departure for its director, Bruno Dumont. The French filmmaker – who has built up a very distinctive, very divisive body of work since making his feature debut with the remarkable La Vie de Jesus in 1997 – likes to go against the grain. He’s expressed a loathing for his national cinema, its moralising tone and emphasis on dialogue, instead favouring a more primal approach that makes use of untried (some would say untalented) performers and has little concern for ‘storytelling’. Yet here is he with a biopic on his hands – and, moreover, a period drama and a costume drama – and one of France’s major stars, Juliette Binoche, occupying the lead role.

Claudel has been the subject of a film before. In 1988 Isabelle Adjani portrayed the French sculptor for the simply-titled Camille Claudel, which was very much a populist affair. It made use of exquisite production design, a sweeping score and Gérard Depardieu as fellow sculptor Auguste Rodin, resulting in numerous awards and nominations, including a pair of Oscar nods. Encompassing the years 1884 to 1913, it focused on Claudel’s relationship with Rodin as both student and lover and ended with her being committed to an asylum at the bequest of her brother, the famous poet and playwright Paul Claudel.

As its title suggests Camille Claudel 1915 opts for a smaller scope than the earlier film, concentrating in fact on just three days in Claudel’s later life. It’s indicative of Dumont’s pared-down approach throughout, one that does away with a score, barely leaves the asylum and favours sparse visuals drained of colour. There’s a temptation to say that Dumont must have screened the 1988 picture in preparation for his own as everything plays out as an opposite, even though it could be positioned as a sequel. Only the subject matter and the casting of key French acting talent serve as connections between the two.

Needless to say, Binoche is central – indeed, Dumont’s framing regularly keeps her front and centre. Yet he also strips her down and pares her back, making her as fragile as possible and pale enough that she almost fades into the stone walls which surround her. Binoche was roughly the same age as Claudel was in 1915 during the time of production, which was very much a conscious decision on Dumont’s part. His film sets itself up as a reproduction, striving to accurately reflect as many of its events as possible; not only in Binoche’s age, but also in deriving its dialogue from correspondence between Camille and Paul or by casting real-life psychiatric patients and medical staff to serve as supporting/background players to his lead.

Those looking for plot won’t find much to chew on. The appearance of Paul Claudel (a fine turn by Jean-Luc Vincent) after the halfway mark triggers some narrative development, but such concerns are comparatively minor. For Dumont the important thing is the investigation: having recreated aspects of Claudel’s confinement as thoroughly as possible, he is free to examine his central character and get under her skin. (This hard stare is arguably the director’s defining feature; the teenagers in La Vie de Jesus, for example, face similar scrutiny.) As such, all he needs are the three days allocated as the film’s timeline and they more than ably sum up the thirty years Claudel would spend confined to an asylum up until her death in 1943. He and Binoche, whose contribution should not be undersold, are able to encapsulate the hopes, frustrations, suspicions, anger and incomprehension in what are, ultimately, just a handful of scenes – and that’s some achievement. Anthony Nield

Cold In July (dir: Jim Mickle. In cinemas now)

Joe Lansdale claims the plot for his novel Cold in July came to him in a dream; and the film adaptation certainly captures this nightmarish quality. Richard Dane (Michael C Hall) is woken in the middle of the night by his wife Ann (Vinessa Shaw), who’s heard an intruder. He finds his gun, creeps down the hallway, and moments later, his entire life has changed. He’s become a killer. The cops assure him it’s a clear case of self defence, and the people of his small Texas town are quick to congratulate him, but Dane’s eaten up by guilt. Things only start to get really bad, however, after the burglar’s in the ground, and Dane’s ambivalence about the killing sets him on a dark, twisted path.

Co-stars Sam Shepard, Don Johnson and Vinessa Shaw give lovely, nuanced, economical performances, but this is Dane’s story and it’s Michael C Hall’s film. He’s outstanding in what is essentially a portrait of a man whose conscience is under extreme duress, conveying Dane’s vulnerability and desperation with subtlety and restraint.

Lansdale’s novel is classic modern American noir, poignant, brutal, morally ambivalent and deeply atmospheric. Cold in July’s strength is in the way it renders that literary atmosphere cinematically. A sensual film, redolent of the oppressive heat of a Texas summer; it uses blurred lights and lens flare, moody thunderstorms and purring engines to evoke a noir sensibility, an oppressive evocation of doomed male honour and wasted lives. Narratively, the film wears its ‘80s setting lightly, with occasional reminders like VHS tapes or an early mobile phone. Aesthetically, though, it’s deeply reminiscent of Michael Mann’s 1986 masterpiece Manhunter, with its gorgeous colour palette, its interior scenes bathed in melancholy turquoise light and its creepy electronic soundtrack.

The film was seven years in the making, and by director Jim Mickle’s own account, a labour of love. The care and skill that he and co-writer Nick Damici put into their stylish adaptation are evident; they’ve taken Lansdale’s novel, stripped out a great deal and made significant changes to the plot, but kept and distilled the essences of characters, relationships, themes and moods. In that sense, it’s a true adaptation, rather than a straightforward filmed version, and all the better for it. Yasmeen Khan

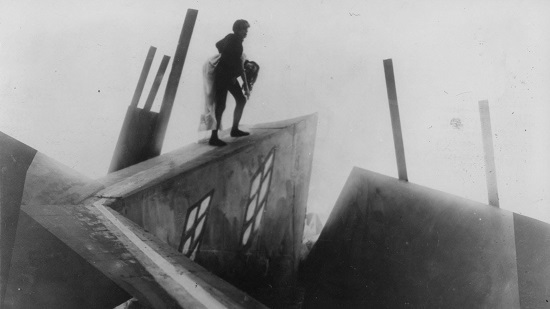

Das Cabinet Der Dr. Caligari (dir: Robert Wiene. In selected cinemas from 29th August)

Robert Wiene’s radical Expressionist masterpiece is set to haunt audiences once again in what’s being hailed as the definite restoration of this German silent cinema classic. Das Cabinet Der Dr. Caligari hits cinemas this week; almost twenty years since the last attempt to restore it to its former glory, and 94 years after it first lay bare the delusions and paranoia of a country on the brink. The film’s camera negative – described by Anke Wilkening, the film’s restoration supervisor as the “silent witness” to the film’s original aesthetic – is employed alongside the best material from all existing historical prints from film archives worldwide.

With its famously serrated stage sets, designed by art director Hermann Warm and painters Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig, Das Cabinet… envisioned a mindscape of psychological horror: a world of eerily vibrating landscapes punctured with the jagged edges of knives, and slow, flat, pulsating flowers. How far Caligari… influenced what came after it is hard to say, but those rich, dark shadows and hard camera angles have their finger prints all over film noir. And it’s fair to say that its early envisioning of externalised delusion made works like The Golem, Nosferaturu and Metropolis possible.

Caligari was the first true horror film, and though modern audiences might find the plodding speed, chapter breakdown and am-dram theatricals a bit too distracting for it to truly raise some hairs, the film’s inimitable vision of projected internal paranoia still holds power. The original film was tinted, and the new restoration has kept these tints, which alternate between dusky yellows, murky greens, reddy browns and purply blues. The Expressionist title cards are glorious and, just as in Fritz Lang’s Woman on the Moon,, I still get a kick from seeing superimposed words striking the air on screen to illustrate Alan’s imagined voices. This new restoration has polished many of the film’s bruises, while keeping its character intact.

But my favourite element still remains the presence of cinema’s dark prince, the inimitable and arch-cheeked Conrad Veidt. Looking like a shoe-in for membership of the Birthday Party about sixty years too early, those hollowed out sockets and translucent skin feels almost as new as the restoration itself. Sophia Satchell-Baeza

Pulp: A Film About Life Death And Supermarkets (dir: Florian Habicht. In selected cinemas now)

“Are you trying to get a snapshot of Sheffield life? The hopes and dreams of the common man?”, asks an interviewee dryly about halfway through this documentary on said city’s favourite sires, Pulp. It’s a question that typifies the self awareness and savvy of all of the inhabitants of Sheffield that director Florian Habicht turns his camera on and the answer is yes, he is, but he’s trying to do a lot more beside, and it’s this level of ambition that, while admirable, serves to ensure that Pulp: A Film About Life, Death and Supermarkets never quite leaves the starting blocks.

A backstage expose; a portrait of a unique place and a unique people; the history of one of the most important bands to come out of the UK in the last century, Common People… is all of these. Thus, inevitably, it’s fragmented pleasures are manifold. If you put Jarvis Cocker in front of a camera he’s going to be an entertaining presence, and scenes of him revealing the contents of his medicine cabinet and showing what brand of tea he drinks before shows are evidence of his extraordinary (and extra-ordinary) star power. The film’s portraits of Sheffield and its inhabitants are also winningly pathos filled and unpatronising. Sadly, the aspect of Pulp that the film is flakiest about is their history, which is made all the more frustrating by the little bits of information that we do get. Keyboard player Candida Doyle talks movingly about her struggle with arthritis, and the footage of their 1988 ‘The Day That Never Happened’ live extravaganza/disaster frames their band-least-likely-to appeal beautifully, while Jarvis is a font of knowledge on his rise and decline, describing fame as: “…like a nut allergy… it just didn’t agree with me.”

There’s a terrific film to be made about Pulp and sadly this isn’t quite it. Habicht doesn’t need to show footage of local choirs singing Common People, or kid’s dance groups shuffling awkwardly to Disco 2000 in order to make his point about the band, its city and its people. Indeed every time he turns his camera toward the crowd at Sheffield’s Motorpoint Arena that connection is made manifestly and movingly obvious by every grinning, singing face. Mat Colegate

The Quietus Film facebook group can be found here