By 1966, Marty had left school and home, first staying at a friend’s place on the Lower East Side, then for a year in a studio apartment on 100th Street and West End Avenue, now the Upper West Side, before moving further uptown, above Harlem between the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, to 184th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue in hilly Washington Heights, the highest point in Manhattan. “I got my own one room studio apartment, with a keyboard in the middle of the room, which was almost the whole room, and a little kitchen.” The birthplace of Marvel Comics founder Stan Lee, and Jerry Wexler, the producer who coined the phrase ‘rhythm and blues’, Washington Heights had attracted an influx of European Jews escaping the Nazis in the thirties, before becoming known for famous African-American residents, including Paul Robeson, Count Basie and boxer Joe Louis. When Marty moved in, Malcolm X had just been assassinated at the nearby Audubon Ballroom, in February 1965.

One evening in 1967, Marty and some local musician buddies were strolling down Riverside Drive after enjoying a few beers in a West End Avenue bar. Passing a smart apartment building a few blocks from Marty’s, one of the guys piped up, “Hey, Tony Williams lives in that building!” This scored a direct hit. Tony Williams was Miles Davis’ drummer, who’d joined his quintet in 1963 as a 17-year-old skins prodigy, after being introduced by saxophonist Jackie McClean. Tony had been like a polyrhythmic rocket going off alongside pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and saxophonist Wayne Shorter, underpinning one of the richest stretches of Miles’ career in one of the finest rhythm sections of all time.

Helped by his bebop musician dad, Tony was known as one of the best drummers in his hometown of Boston by 15, already playing with tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers. Both musicians had been introduced to jazz by local tenor saxophonist Rocky Boyd, who Marty had recently met and saw regularly when hanging out at the Village Vanguard. Rocky had moved to New York in 1958, sharing a loft with newly-arrived drummer Sunny Murray, who he also encouraged. He was an overlooked but pivotal catalyst who recorded just one album in 1961, with trumpeter Kenny Dorham, although he played with Max Roach’s Quintet and Miles that year.

Tony Williams was still only 16 when Jackie McClean noticed him and, with his family’s permission, whisked him to New York. Then Miles saw him, writing in his autobiography that Tony “just blew my mind he was so bad… I could definitely hear right away that this was going to be one of the baddest motherfuckers who had ever played a set of drums.” Prompting Miles to bring the rhythm section further forward, Tony played on nine studio and nine live albums, including 1965’s E.S.P., 1967’s Sorcerer and Nefertiti, 1968’s Miles In The Sky and Filles De Kilimanjaro and, as his parting shot, the seminal In A Silent Way.

Marty’s daily routine in the week revolved around practicing on the large keyboard set up in his room. One day, when he was “in the middle of the usual daily ecstasy of exalted playing, work studying and playing with records, or whatever I was thinking about at the time, making it even more exalted”, a thought kept nagging him; Tony Williams, Miles’ great drummer, lived just down the road. The mission became clear. “Tony’s like seven blocks away, I gotta talk to him.” So Marty duly made his way to the apartment building, scanned the names by the door-bells and, summoning the front which got him into the jazz clubs, rang the one marked ‘Williams’. “Hello,” said a voice, which had to be Tony. Maybe caught unawares at the simplicity of the operation, Marty quickly thought up an opening gambit. “I’m a keyboard player and I’d like to study with you. Can you teach me?” “Come on up,” said the voice.

“It went from there. We were both so young. Tony was only a couple of years older than me. I think he just really liked the idea that I was a keyboard player. I was really serious. I thought it would be a great idea, and I think that’s what got Tony’s ear too, because I was a piano player wanting to study with a drummer. If anything, it doesn’t usually work that way, ‘Here’s this kid asking if he can study with me’. But he was always growing, and looking to learn too. He was studying keyboard too, so I think he liked the idea of teaching and being close to the piano side. It was novel for him. Sometimes he gave me tunes that he’d written for me to play. Tony was like me, he always had a book in his pocket. He had a harmony book he was always reading, which he’d pull out when he went to gigs like the Vanguard. He befriended me, and literally took me under his wing for a while. Years later, I thought ‘How generous he was to do that’, because he didn’t have to.”

The friendship between the driven young keyboard player and ever-questing superstar drummer blossomed over a couple of years, Marty witnessing many Miles shows while continuing mutual discovery sessions with Tony, although any drumming was out of the question because of the neighbours. “I would have loved it, but we couldn’t play at his place. He wasn’t playing drums in his apartment, but to study that way would probably have been incredible.” Marty did get his chance to play with Tony, in front of an audience, and remembers it like it was yesterday, excitement rising in his voice as he recalls the epic jam session they attended at the loft of pianist Art Murphy, who had studied at Juilliard with Steve Reich and Phillip Glass, and become a founder member of their respective Ensembles. Jazz was Murphy’s true love and, while at Juilliard in 1963, he’d worked with Hall Overton on arrangements for Monk’s big band concert. He was also a close friend of Bill Evans, and had transcribed solos for him.

At weekends, Art liked to kick back with jam sessions, inviting a nucleus of musicians to provide the bedrock for a stream of guests. Marty only knew Art as “a piano player who didn’t play out a lot. He was like an insider cat they all knew. Musicians used the occasion just to come in and play with different people. Tony was too young to just fall into one thing, he was always growing. Just playing with Miles might have seemed enough, but he was always looking to do more and experiment, so he’d do that kind of stuff.”

Tony invited Marty, suggesting he come by his apartment and they go together the first day. Marty remembers being struck by the woman Tony was living with. “She had such quality, very high class in all the right ways. I was impressed with her right away. She was there, and a couple of friends. We all got along good, kind of kidded around in the street then got in a cab.”

There was a lot to take in that first day. Seduced by the heady refreshments and informal atmosphere of masters at play, Marty was content to just watch as Art held down the grand piano, accompanied by a rhythm section of Tony and double-bassist Juni Booth, who had recently blown in from Buffalo, and was currently playing with Art Blakey and Sonny Simmons (and would join Tony Williams in his band Lifetime the following decade). “I didn’t play that first day. There weren’t many piano players so Art did most of it, but he had a lot of horns. There were so many musicians, a lot of people coming in and out. Sam Rivers came over and stayed for two days.”

For the second day, Tony decided to give Marty a piece he had written, to play for his loft debut. Returning to Art’s loft, Tony settled behind the drums and, about 90 minutes in, said, “Go ahead Marty, you play this one,” and they were off. “That was cool, they’d do that once in a while. I think he wanted to hear something he had written, but it was incredible. By that time, I was so loose and warm, because I was familiar with the guests and the setting. I don’t know how it would have sounded the day before, but by now I was very relaxed. When it was time for me to play a solo, it just came out as if from a tube of toothpaste. It just flowed. And Tony’s playing behind me. I can still hear it, and feel it. It’s a sensation you get when you’re playing with certain people. Tony was such a rich accompanist. What he laid down, I had never felt before. One of Tony’s innovations was to play the hi-hat cymbal on all four beats, it was usually done in two and four. It was almost like a rhythm guitarist playing on every beat, like a pad, a total mattress under you. He also did this innovation with his ride cymbal. Where most guys went ‘dink dink a-dink’, Tony was doing about five of those on each beat, so fast and so smooth. With the combination of that, and what he did with a snare, it was like flying in an aeroplane, or being on a cushion of clouds. That one track, and that was it. Art went back to playing, everyone kept playing in different scenarios. Nobody commented on anybody. They just kept playing, trying to do as much as they could in the time that was there. I knew it sounded fine. It was like there, you know.”

Although Marty took pains not to impose himself on Tony when he was playing gigs, he’d often hang out with the Miles Davis group when they played the Village Vanguard and Village Gate. “I used to go down and hear them at the Vanguard a lot. Herbie Hancock and them would be talking and we were sometimes all in proximity of each other.”

The Village Gate on Bleecker Street was already one of Marty’s regular haunts. The building it occupied started life in 1896 as a workingmen’s residence, then a flophouse called The Greenwich Hotel before it became a Beat-friendly coffeehouse called Jazz on the Wagon. It became one of Manhattan’s most legendary niteries in 1958 when it was converted into a club by promoter Art D’Lugoff, who booked in the top jazz names of the day, including Miles Davis.

“I never met Miles but I used to see him,” says Marty. “I wouldn’t have said anything to him, although we did have an interesting moment at the Village Gate when Dizzy Gillespie was playing.” It happened during Miles’ August 1967 stretch at the club with his original mentor Dizzy, who was now 50 years old. “This was not too long after Tony and I were in pretty close contact. Tony told me Miles was playing down there. I didn’t sit at a table, I sat at the back of the stage, where the dressing room was. There was a long row of chairs for musicians. It was very loose like that, informal. I didn’t want to sit at a table, so I sat on a chair. Miles shows up to do the show. You can see he’s in very good spirits, looks like he’s just come out of the gym with a tight shirt and a smile on his face, ready to play. Everybody’s starting to show up, including the musicians.”

First Dizzy came on, doing the career-straddling act that was now closer to cabaret, but he was still the daddy of it all. “When Dizzy started playing Miles came out of the dressing room and just watched. By this time, what Dizzy was doing was not modern. I knew Miles knew that for sure, but he stood and watched Dizzy like a kid looking at his trumpet teacher or father with the utmost respect. You could see that he would always look and listen to Dizzy that way, no matter what he did. I noticed that and then, Dizzy went into a carnival burlesque thing where the drummer takes a rubber chicken out of the bass drum and holds it up to a drum roll. It’s the comic scene, which was so incongruous to anything in modern jazz. They loved it, the whole place started laughing and roaring, the entire audience is in a carnival. But it didn’t make me laugh at all. So I turned my head a little bit to the side, and I catch Miles turning his head to the side and looking me straight in the eye. My eyes caught his looking at me, and I looked at him. I realised that we were the only people in the whole room that weren’t laughing. That was Miles and myself totally… crossing paths.”

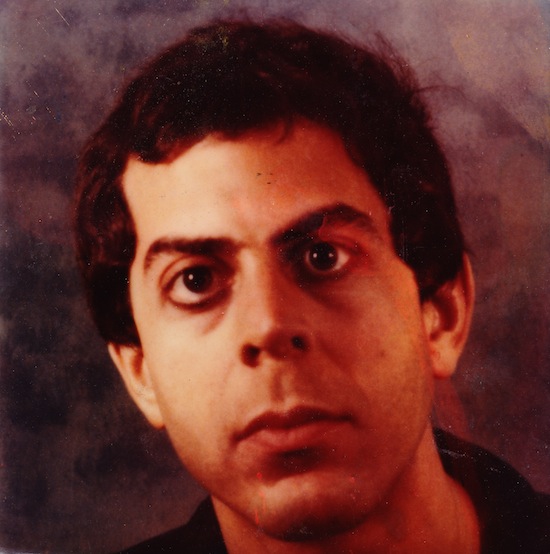

A young Marty Rev

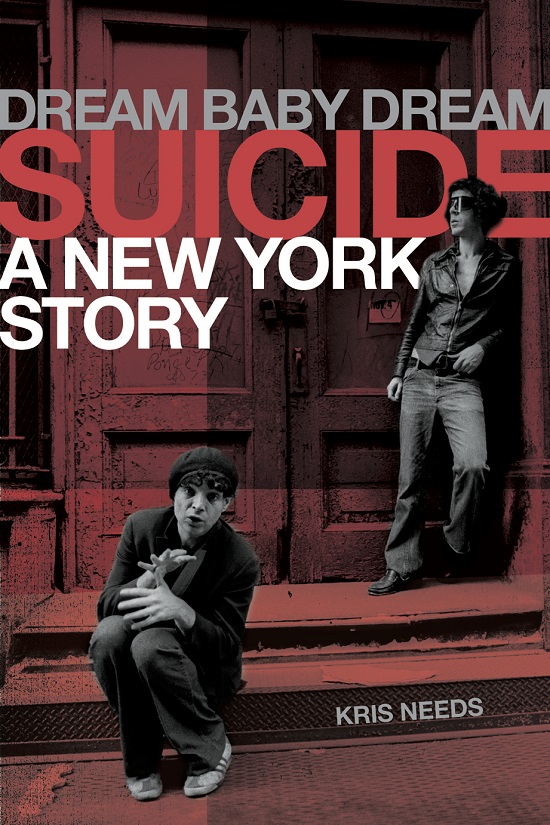

Kris Needs, Author of Dream Baby Dream, Q & A

Suicide are one of those bands that really make a big impact on people – describe the first time you heard them.

Kris Needs: I actually knew about Suicide four years before I heard them, after reading Roy Hollingworth’s review of a 1972 Mercer Arts Center show in Melody Maker where he described them as "the starkest trip" he had ever experienced and "the most frightening blend of music going on today". That left a big enough impression on an 18-year-old me craving Velvet Underground-style magnificence and a new noise to pounce on the first record which came along bearing their name, which happened to be ‘Rocket USA’ on the Max’s Kansas City 1976 (compilation) album. At a time when punk was girding its loins with a rock & roll template this threw an entirely different curve into the mix, although it was the most punk and most bare-boned rock & roll I’d ever heard. Suicide also seemed somehow descended from the Miles Davis, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra and Silver Apples albums I’d long worn smooth. Then along came an advance promo of the first Suicide album a little while later and I was never the same again!

Did you ever see them live and if so what was it like?

KN: Several times over the years and each one very different. The first was absolutely in-at-the-deep-end, being when they were supporting The Clash on 1978’s On Parole tour. In those days I was editing Zigzag magazine and The Clash were one of our main bands so I went on the tours. I remember the night around Mick Jones’ flat when he had just got the Suicide album and we were picking over it like an alien meteorite which had dropped out of the sky. Around then it was announced that Suicide had been asked to do the tour. I was already aware of the hostile reactions Alan and Marty were getting in the US, even at so-called broad-minded punk venues such as CBGB, so knew the British crowds who’d gobbed on Richard Hell the previous year were going to have a meatheads’ picnic with Suicide. Predictably, the conservative boot boy element couldn’t handle properly confrontational New York future noise achieved without guitars or drums, and reacted like the torch-bearing villagers in a Frankenstein movie.

The night I particularly remember was when I was standing in the wings of London’s Music Machine and the baying redneck lynch mob hurled everything they could, verbally or physically, at the pair. Alan stood like a skipper in a gale, taunting them to further befuddled heights while his sharkskin suit turned from purple to black under the relentless bombardment of gob, beer and liquid fear. Strummer reckoned Alan was the bravest man he’d ever met. That aside, hearing Rev kick up the generator rumble of ‘Rocket USA’ and Vega announce, "It’s doomsday" over his escalating cacophony remains one of the great gig moments of my life. I’d seen Ziggy Stardust, the New York Dolls and Sex Pistols from close quarters but the sonic bombardment whipped up by Suicide was more overwhelming than anything I’d experienced. Where did this come from? I’ve spent the last 37 years trying to find out.

Another one that stands out is CBGB in 1986. Suicide on home turf finally being hailed as returning heroes in a club which used to see them fleeing for the exits. They turned in a performance of coruscating soul power. That would often be the case from that point on.

What are people’s biggest misconceptions about Suicide?

KN: That they were only hell-bent on churning out mindless racket with few discerning subtleties and deliberately provoked crowds. Suicide might have been first to use the word "punk" on posters etc. but were formed as a confrontational art statement amidst the rage against the Vietnam war gripping downtown New York back then. Alan was an artist who was propelled to take his rage to the stage after witnessing Iggy and the Stooges in 1969. Marty was a long-time doo-wop fanatic who had spent the previous decade single-mindedly learning the skills and rudiments of jazz, which he then used as a launch-pad to start exploring unknown terrain. They could never have blueprinted synth-pop in any way apart from the two-man singer-and-synth lineup. They never set out to be hated, although Alan would stop at nothing to get a reaction, absorbing hostility and spitting it back out. They are also two of the loveliest people you could wish to meet – when they’re not on a stage!

For such a hip/legendary band, people never manage to copy Suicide’s sound well do they? What makes them so inimitable?

KN: It’s impossible, especially when people imitate the wrong elements. Failing to understand the above doesn’t help either. Suicide have been left out of the history books, even about NY punk, and documentaries purporting to tell the story of electronic music too often. While writing the book, trying to explain what influenced and went into the creation of Suicide, it was always so obvious that they were absolutely unique but also completely of their time and place. It further explained why many have tried but nobody has managed to replicate them. Not just because of their influences or experiences either – Marty’s keyboard set-up has defied earthly laws for decades and there will only ever be one Alan Vega!

Do you see Suicide as a gateway into a time/mindset that has gone now or does their spirit live on elsewhere?

KN: Their spirit is indelibly (although often subliminally) ingrained in today’s music, with many devotees proud to fly their flag but often several generations passed down. They are the last band to emerge from New York in that pivotal era still functioning with the same lineup. Although Alan’s activities have been a bit restricted after his stroke a few years ago, Suicide still represent a time when music delivered with fearless passion, uncompromising attitude and genuine anger could have a seismic effect, even if it would even take years to be acknowledged. Suicide are a unique, magical beast which happened when two disparate personalities collided and clicked. It happens very rarely and even then, as with Lou Reed and John Cale, usually doesn’t last too long. I also see them as mirroring New York over the 45 years since they formed; a monument to the city’s lost vitality and funk, forever standing like an animated skyscraper which long ago defeated the flame-breathing monsters trying to trample it into the dust. The spirit of Suicide will always be standing tall even if the metropolis which spawned them turns into another city.