If mysticism lives on in aesthetic experience, then this comes at the cost of acknowledging that art is utterly marginal to the economic and monetary forces that govern our lives. There is no question of going back to a medieval monastery as a safe haven amidst the darkening age of the world. What is done is done. God is dead or at the very least transmuted into Mammon.

But the mightily peculiar thing is that it doesn’t feel that way when we listen to music, when we allow ourselves to surrender to that experience. We know that the modern world is a violently disenchanted swirl shaped by the speculative flux of money that presses in on all sides. Yet, when we listen to the music that we love, it is as if the world were reanimated, bursting with sense, and utterly alive. The only proof of animism I know is music. When we listen, it is as if the world were influenced by a natural magic. In music, the cosmos feels alive, divinely infused.

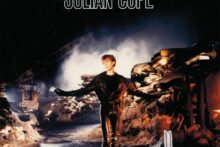

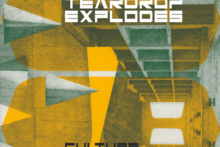

Abstractions risk becoming banalities, and so concrete examples are vital. With that in mind, and for the sake of a certain formal symmetry, I’d like to add one more Julian to the list that we have assembled in this book. This time it is a true saint – Julian Cope, founder of the Liverpool post-punk band the Teardrop Explodes. Saint Julian is also a solo performer with an extraordinary volume and breadth of music, as well as being an enthusiastic amateur archaeologist with a passion for British and European megaliths. And he is also very funny, with a gift for punning album titles, mostly at his own expense: Floored Genius, Self Civil War, Rome Wasn’t Burned in a Day and, of course, Saint Julian.

For my purposes, the key book is Cope’s Krautrock Sampler, which was published in 1995 and has been out of print since 1996. The unavailability of this book appears to be a calculated act, as Cope said he was fed up with wan-faced legions of music blokes or nerds endlessly pointing out his errors and omissions. Cope is not a ‘completist’, and he only writes about records that he has in his library. Krautrock, the wildly intense music that emanated out of the former West Germany in the late 1960s and early ’70s, is what Cope variously and deliriously calls primal punk, Ur-punk, magick punk, Gnostic punk, “punk as eating snot off your mate’s face.”

Where Julian of Norwich experienced her first showing by looking on a bleeding crucifix as she lay at the threshold of death, Julian Cope experienced his revelation while lying in a caravan in Tamworth in Staffordshire in 1972 listening to the John Peel show on the BBC. He would have been around fourteen or fifteen years old. The song that Cope heard, where his attitude “to ALL music changed,” was ‘Hallogallo’, the ten-minute-long opening track on the first album by Neu! Cope writes,

A bass-less motoric leads ‘Hallogallo’ from a long fade into straight ahead E-major riff-less grooving. Behind it, intermittent backward guitars punctuate like seagulls on echo-less cliffs. There is no melody. There is no vocal. There is nothing to tell you where you are in this seamless corridor with no end. If Neu! had split right after the opening track of their first LP they would still have changed rock ’n’ roll.

This makes perfect sense to me. I experienced something similar lying on a settee listening to the same Neu! track in Letchworth Garden City in Hertfordshire a couple of years later. Many, many thousands of others had analogous experiences. Here music triggers the energy of religious conversion. Suddenly, the world and your place in it shifts and everything opens up in a different way, forever. World de-worlds, creation decreates, and a vast nothingness seizes the back of your throat and the top of your head. Things start to tingle.

There is a well-known origin story about punk that traces it back to the influence of three American bands: the MC5, the Stooges, and the Velvet Underground. There is no contesting the world-historical importance of each of these bands, and of the Stooges second album, Fun House (1970), which Iggy Pop described in 1976 as “the ultimate blowtorch of savage nihilism.” The Stooges took the convenient framework of rock ’n’ roll and gave it the sound of mass production: industrial Detroit drill hammers. Iggy also showed the error of human existence, the breathless nearness of death, and the lure of fun and action. He was like a much better-looking version of Schopenhauer.

Yet what is missing from this origin story is the sheer extremity of being which was the effect of a generous armful of bands that appeared in West Germany after the breakdown of the post-war consensus that accompanied the long chancellorship of Conrad Adenauer, from 1949 to 1963. In the 1960s, there was a new sense of the murderous ugliness of the recent German past. German youth looked at their parents and grandparents, aghast at their silence about the Second World War and the Holocaust. In the insurrectionary political context of Germany in the late 1960s, bands, sometimes emerging from communes and similar social experiments, broke free of the influence of American and British rock ’n’ roll. Let me name the names: Amon Düül I and II, Tangerine Dream, Faust (whose name means “fist” in German and who even wrote a song called ‘Krautrock’), Cluster, Harmonia, Guru Guru, Popol Vuh, Ash Ra Tempel, Kraftwerk, and the mighty, mighty Can. Cope (who is a tiny bit eccentric, it should be remembered) describes Krautrock as

what punk would have been if Johnny Rotten alone had been in charge – a kind of Pagan Freakout LSD explore-the-god-in-you-by- working-the-animal-in-you Gnostic Odyssey.

Saint Julian has a way with words.

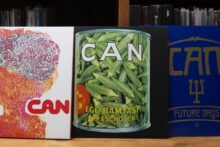

All these bands are important, especially what Can managed to produce in a series of early albums from Monster Movie (1969) to Future Days (1973), passing through the lysergic splendor of Tago Mago (1971). I would like to invite the reader – kindly but insistently – to listen to some or all of the eighteen and a half minutes of ‘Halleluhwah’, which originally occupied the entire side of a double album. When Can began, they were seasoned musicians, most of them in their thirties. Irmin Schmidt and Holger Czukay, two of the founding members, had been students of the experimental composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and their drummer, Jaki Liebezeit, had been playing free jazz for many years.

What is so striking about ‘Halleluhwah’, as Cope points out, is its exploration of aesthetic restriction, the minimalism of Can’s approach. I have spent more days and nights in my life than I care to confess just listening to the almost monotonous kick and snare drum patterns of Liebezeit, feeling something come alive inside me with the insistent pulse, waves of vague keyboards, spidery guitar, and the huge, simple clam-like bass lines of Czukay, which sometimes consisted of one note. But it is the right note. Yes, sometimes life can be that good.

Yet in terms of the art that formed a template for the music that we call punk, much of it rising out of the recessionary rubble of post-imperial Britain, pride of place has to be given to Neu! They only existed for three, really rather brief, albums: Neu! (1972), Neu! 2 (1973) and Neu! 75. Everything they did was mediated through the space-time shifting brilliance of the producer and sound engineer, Konrad “Conny” Plank, often recording in his handmade wooden studio in Wolperath, on the southern outskirts of Cologne. This is where Plank encoded new patterns for what the ignorant call noise, and where he laboriously crafted compulsive new rhythms of existence.

Just listen to the pneumatic drills at the beginning of Neu!’s ‘Negativland’ and how they merge and meld into a blank, motoric sweetness (it might sound odd, but there is a sweetness in these machinic rhythms). The contradictory creative forces of guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger were held together like two sides of a paradox, or the white and the yolk of an egg: interdependent yet clearly distinct. As with Lennon and McCartney, or Morrissey and Marr, Rother and Dinger were always pulling in opposite directions. Of course, they fell apart. Rother moved into the lush harmonies and tunefulness of Flammende Herzen (1977) and Sterntaler (1978).

Klaus Dinger preempted the entirety of punk in the powerful, drum-led, apparent dumbness but actual sublimity of La Düsseldorf (1976). The only lyric on the first two tracks of that album, which add up to around twenty minutes, is the repeated name ‘Düsseldorf’, which is like an English band just saying “Coventry” over and over again, or an American band saying “Akron, Ohio” (which indeed happened with the band DEVO a little later). Somehow, it is intensely moving and makes me think of the utter base materialism of the artist Joseph Beuys, who taught at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf throughout the 1960s, until his dismissal in 1972. What is so striking about Beuys’s obsession with material substances like felt and fat, wax and wood, is the fact that for him – as someone who self- consciously made art as a mystical shaman – matter never stands in opposition to the spirit, to the airy lightness of radio transmissions and the vapor trails of fighter aircraft. Matter is incarnate spirit.

On Neu! tracks like ‘Hallogallo’ and ‘Für Immer’, everything seems to move relentlessly ahead, rhythmically pressing, pulsing, and pushing while at the same being mesmeric and melodic. It makes no sense that a piece of music can achieve such simultaneously opposed effects. And all this without the assurance of a bass guitar, any discernible song structure, or any of the formal features of rock ‘n’ roll. This music’s mystery is its utter simplicity and obviousness. Nothing is hidden.

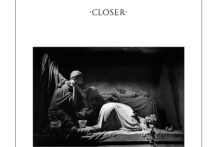

New aesthetic rules for music were being written. All Joy Division did was to add some lovely, cribbed Iggy words. Just listen to Neu! 75, which both prefigures and completely surpasses all that is interesting in punk and much post-punk, where Neu!’s ‘Hero’ becomes Bowie’s Heroes (1977), and on through to the Cure’s Seventeen Seconds (1980). And yet Neu! had already exhausted and surpassed themselves by this point, and there is something already nostalgic about their last album, Neu! 75. They had created entirely new aesthetic forms, perfected them and abandoned them like husks, pupae, or chrysalides. Genuinely new music doesn’t stay in place for long.

Coming back to Julian Cope, the track that captures the mood of Neu! perfectly is the first single by the Teardrop Explodes, ‘Sleeping Gas’ from 1979. This track has one riff – one five-note bubbling bass pattern, no drum fills – in an ever-repeating and developing, deepening musical loop. If you don’t know it, please listen to it, as it is damn-near perfect:

Sometimes I wonder if you’re really living

What is this feeling you think that you’re giving?

Punk should be fearless, amoral, born from a spirit of defiance, refusal, and the celebration of a vertiginous dizzying freedom. Punk songs are Novalis-like romantic fragments pressure-cooked in the hell of the post-industrial world. With a fearless imagination and a dauntless, beautiful naivety, these songs open a space where we can push back against the pressure of reality. Punk’s raptures are mystical.

On Mysticism: The Experience of Ecstasy is published by Profile Books