Around a month ago I was invited to attend Zona Nouă poetry festival (‘new zone’ but also, I think, ‘zone nine’) in Sibiu, Romania (in the Transylvania region). I went knowing very little of Romanian poetry, apart from a 2010 interview with ‘utilitarian’ poet and orthodox monk Adrian Urmanov, which, on rereading, I can see has had a lasting and mostly discomforting affect on me. (It’s good.) I also have a poetry anthology edited by David Morley with Urmanov from 2007, called No Longer Poetry: New Romanian Poetry (Heaventree). The book features eleven poets from the ‘2000 generation’, whose work came to prominence over the decade after the fall of Communism, in the violent revolution of December 1989.

This is a passage from the book’s introduction, written by Urmanov (under his given name Leonard-Daniel Aldea – the double-namedness of things seems to be an obsession of Romanian poets), about the situation of poetry immediately after the collapse of the Ceaușescu regime:

The revolution failed to act as an instant switch between Communism and

Democracy…Instead, Romanians found themselves in a grey zone, one where

attributes of the free world competed with, and attempted to complete, the

outline of what was really a ghost of an economy and country.

‘In poetry,’ he goes on to argue, ‘the change was sharper’: the revolution obviously deposed the official poets of the state, whose books were distributed by the hundred thousand, but it also neutralised the poets of ‘true expression’: those who revealed the political reality in Romania, or at least insinuated it – these unsponsored, dangerous poets also abruptly ‘found themselves useless.’

The 2000 generation (three or four of whom became monks just like Urmanov, I learned) were concerned with responding to the disorientating new conditions of the ‘grey zone’, and, through famously concerted workshop practice and discussion, rediscovering a purpose for poetry there (a poetry ‘after poetry’). The situation that Romanian poetry faces a decade and a half later is different again. All of the poets who read at Zona Nouă came of age, and most were born, after the fall of Communism – at 33 I was the oldest reader at the festival by five or six years. The work of these poets, newly networked, separated from previous generations by their drastically altered conditions, seems like both a development and a departure – more spontaneous and responsive, yet no less alert. In the ‘new zone’, technology is combining with the social potential of literature to affect its terms as well as invent its poetry.

Several writers from other European countries read alongside the Romanian poets, and the overwhelming impression I took from the visit is the insane privilege of being an English-language writer (especially if like me you’re a monoglot). Obviously this is something I was already aware of, but it’s still a striking and humbling experience to see it play out over all kinds of interactions and relationships. Like other forms of privilege, rather than being one possibility of many, the apparent invisibility of its dominance is partly what’s so powerful – English is the assumed backdrop, the automatic mode, the meeting place that goes without saying. To appear in Romanian, poems written in Slovenian or Portuguese had to arrive there via English translations. A trip to an independent bookshop in Sibiu (only the second established in the city after Communism) emphasised this imbalance – many English and American titles familiar to me were available in Romanian translation, while it remains rare for even significant Romanian authors to be translated into English and to receive proper distribution, let alone attention, in the UK or the US.

I’d like to take the opportunity to focus briefly on a few of the poets I met in Sibiu, who I think it’s unlikely readers will have come across. Among my notable omissions of those in attendance are Oscar Bruno D’Artois (France/USA), Luna Miguel (Spain), and Lucy K. Shaw (UK), who are absent only because they may already be familiar to you. If not you should click on their names. You can find a full list of poets on the festival’s website.

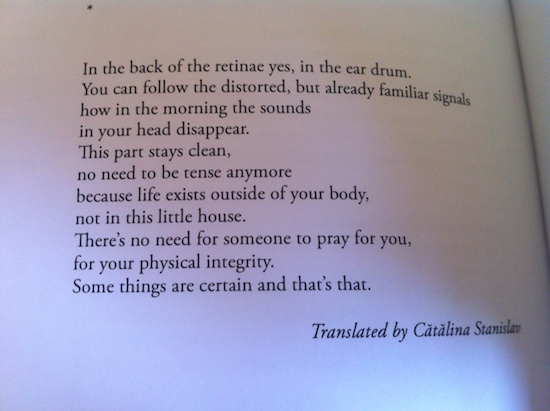

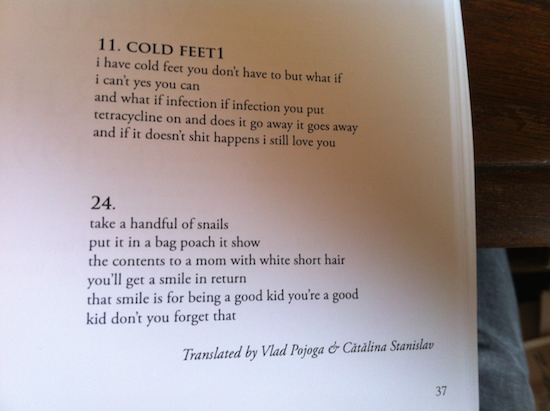

The readings took place on the roof of the public library, and were hosted by the festival organisers, Vlad Pojoga and Cătălina Stanislav, themselves poets and key presences in this group of writers (to read poems click on the names). I’m listing the poets in the order I met them.

Katja Perat (1988) is a Slovenian poet based in Ljubljana. She is also a columnist, and is currently writing a libretto based around the female characters in 1001 Nights. Her poems are sharp, witty, self-aware, and seem to articulate a particular state of mind or perspective on things that feels humorous and authentically helpless. We talked about David Foster Wallace being overrated; Katja also does an amazing Žižek impression and invented the concept of ‘Žižek karaoke’. Her second book is called Davek na dodano vrednost, meaning ‘Value-Added Tax’.

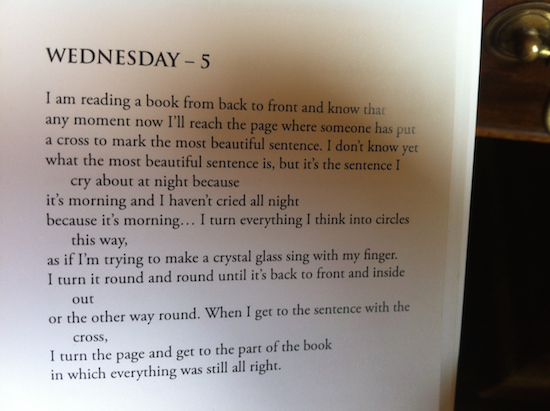

Lieke Marsman (1990, Amsterdam) published her first book at the age of nineteen: Wat ik mijzelf graag voorhoud, (Things That I Tell Myself, or What I Keep Telling Myself). It was funny to hear Lieke describe the division in Dutch poetry between a traditional male-dominated establishment and more diverse youthful movements, as almost every poet at the table confirmed this was the case in [their country] as well. She used to play tennis seriously, and we talked about 17 year-old Michael Chang’s famous 1989 victory at the French open, when he served underarm due to cramps, and relied on ‘moon balls’ to move around the court. Lieke’s poems seem interested in patterns and circularity, and in how structures from fiction can invade real life. I recommend her poem ‘Love in Times of Solitude’, too long to feature here.

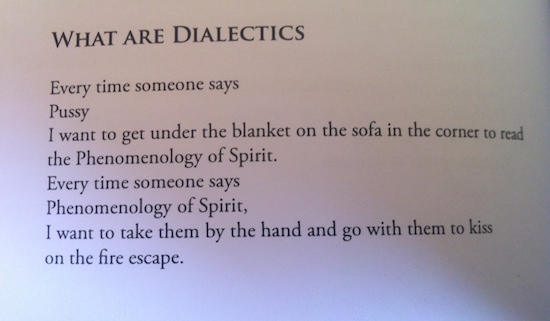

Vlad A. Gheorghiu is a Romanian poet born in 1992; he published his first collection in 2013. Influenced by the Beats, he has translated Gregory Corso into Romanian, and is currently working on a translation of Leaves of Grass. He told me that the Beat poets were translated into Romanian under Communism, but most mentions of ‘freedom’ was translated as ‘nature’, and any longer discussions of ‘personal freedom’ were translated as being about ‘the emancipation of the workers’. The sheer blatancy of the ideological intervention could seem funny to a Western writer, but I have to admit I was kind of shocked by this. Later I wondered if this had anything to do with the general aversion to the topic of nature in all of the Romanian poets I heard – if the very idea of ‘nature poetry’ might be tainted by its longstanding association with the official art of the state. Vlad’s poems are often short: their construction is blunt yet agile, trying to escape the situations they trap themselves in. His curtailed use of line is immediately appealing to me (see above).

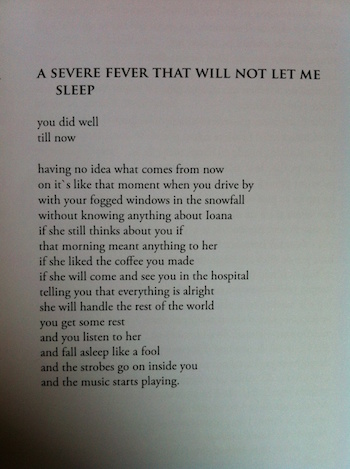

Deniz Otay (1993) was born in Suceava in northeastern Romania. Deniz was the only poet I really talked to about the range of Romanian poets at the festival – I asked her if there was any formal association, like that of the distinct groups from the 1990s I’d read about. She explained there is no formal ‘group’ or manifesto, but more an unspoken similarity or sympathy in approach. In some cases this is characterised by a reluctance to explain the work or reveal its objectives. This feels like a sharp distinction from the 2000 generation, whose entire methodology was bound up with the discussion of poetry’s tactics. Eight years on, the introduction to No Longer Poetry sounds in places a little fanciful in its explications of the nature of authenticity, the prioritising of the poem’s ‘message’, or of strategies used to entice a popular readership – this foregrounding promises more than the poems can deliver. But the interest in creating a poetry readership has carried over. The most notable aspect of Zona Nouă was the youthfulness of its audience: most were aged around 15-22. Some had travelled for two hours or more to attend. The work of these poets, largely unaffiliated with curriculums or universities, has the ability to connect with younger readers in a way that poets in the UK would probably envy. While part of this appeal is clearly to do with the ‘new zone’ of the internet, the directness of subject matter and acute treatment of language is also important – and if there is a uniting feature, it is the particular, wry sort of distrust or cynicism that often enters the work alongside more direct and visceral impulses. Sometimes this appears as an unusual combination of distance and intensity; above is an excerpt from Deniz’s long poem in parts, ‘The Conversation’.

The last poet I’ll look at is Vlad Drăgoi (1987), an apparently central figure in the current scene. His second collection Methods (2013) (his first book he has disowned) is half made-up of poems detailing extremely violent fantasies, while his third book has on its cover the image of a small songbird perched on a reed. The discrepancy is successfully disconcerting. Undoubtedly confrontational, it’s hard to make many assumptions about his poetry: his approach is evasive, and the poems often disturb only to disarm the next moment with images of a more traditional ‘poetic’ value. The laughter I heard at his reading was not the result of something simply comical (though his poems are funny) – it was also the laughter of surprise, of seeing a convention overturned, the laughter that happens when something is just ‘good’. Many of the poets I met published their first collections young, at 20 or 22, but Vlad’s knowing adjustments, responses and corrections to his own reputation seem particularly representative of the self-reflexiveness that makes this generation so interesting: maybe this could be interpreted as an heightened suspicion of poets with a fixed agenda.

This troubling of authorial identity made me think about the city itself. Quiet and picturesque, traces of Sibiu’s receded past reappear frequently from a history that is almost submerged – the shell of a disused Communist factory stands in the middle distance when you look over the city from the Bridge of Lies. The distinctively ocular windows, known as the ‘eyes of the city’, (once noticed they are suddenly everywhere), heighten a sense of historical surveillance, the presence of a watchful past.

The outlines of an alternative reality seem to inform the smartness and vigilance of these writers. Despite huge transitions, poets in Romania remain concerned with insinuating the truth of their situation, which, with the increased presence of technology and social media, has moved closer to that of Western Europe or the US. Urmanov’s assessment of England – “There’s nothing threatening about England, except, perhaps, the safety itself” – can’t be said to apply to Romania yet. But if something poets can show us is how to reveal the actual threats disguised in the presentation of our culture, then maybe the alertness, boldness and scepticism of these young writers can help us identify those dangers – to recognise the anonymous windows, the shared histories, where their eyes meet ours.

All poems from the Zona Nouă festival anthology, copyright remains with the authors.

Further reading:

Of Gentle Wolves: An Anthology of Romanian Poetry

No Longer Poetry: New Romanian Poetry

Sam Riviere is the author of Kim Kardashian’s Marriage (Faber & Faber, 2015).