Photographs taken for The Quietus, by Phil Sharp

(This interview is part two of a two part feature, you can read the first instalment here.)

In Wales I visited the Anglesey colonies of Ynys Feurig, Cemlyn and the Skerries. The Ynys Feurig colony had been an important one for a long time, and was situated on a small island which was accessible from the shore at low tide. This meant it was vulnerable to accidental disturbance from people, and was one of the targets for egg collectors, too…

—Mark Avery, Fighting for Birds

Hello babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies: ‘God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.’

—Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

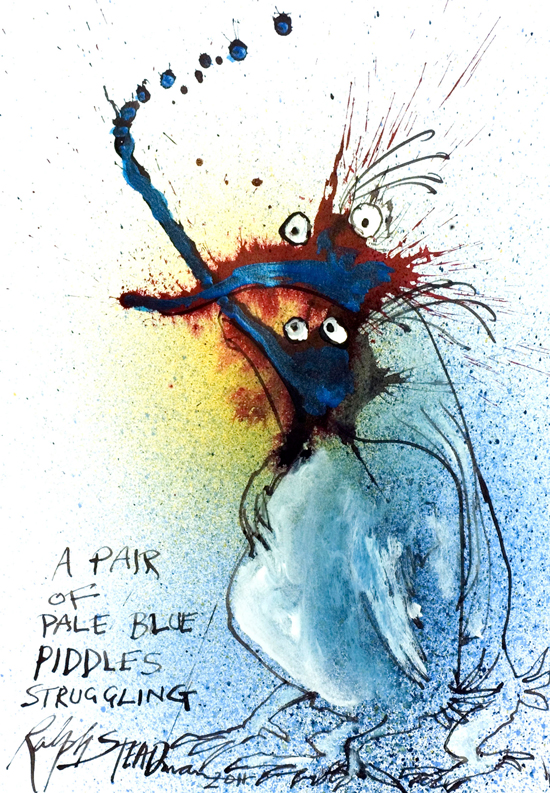

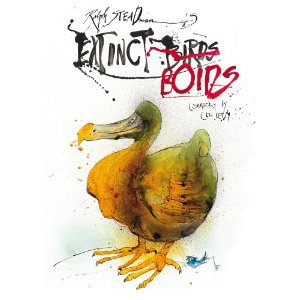

THE PERSECUTION OF peregrines started it for Ceri Levy, the conservationist and film-maker whose current project The Bird Effect brought the book with Ralph Steadman, Extinct Boids, to life. But behind the off-the-wall talk of the Pale Blue Piddle and the Mechanical Botanical Spunt – both birds which crop up in the book – is a protector’s clarity about the importance of the natural world.

However there’s no despair. Extinct Boids is a book born from two unique humours, as became clear in part one of this interview; the conversation now extending into the idea of aging, the importance of kindness and – more than fifty years after his fateful introduction to Hunter S Thompson – Steadman’s own idealism about what it meant to become an illustrator in the first place.

Is there anything in the idea that we all age at the same rate – be you an artist, a banker, or whatever?

Ceri Levy: Age is a really interesting thing because as you get older it means less. I remember being at school and if you had a friend that was in the year above or the year below you, it was almost suggested that was an abnormal relationship. But as you get older, you realise that age means absolutely nothing. It’s people’s minds that are important. A mind can be something that clicks with you at any age! So it’s something I’m discovering: people I used to think of as much older, sort of role models or whatever are actually not that far away. There’s a shrinkage of time anyway, as you grow older. But there’s also a shrinkage of how you perceive age, and what that actually means.

Ralph Steadman: Well now, my father had a very good attitude towards the whole thing. He lived to be 93. And he said, at the age of 87, that the only thing he noticed about growing old was the undertaker raising his hat to him.

He was quite good at that sort of thing; he used to play with the language quite well, actually. He should have been a writer but he became a ‘commercial traveller’. He travelled in ladies’ knickers! I used to go with him on his travels sometimes, you know, round Chester and Manchester and Liverpool, Birkenhead and places like that, up in Cheshire. He travelled around that area, so occasionally, on holidays, I’d sit in the car with him and give him company, as he was m’dad.

I’d wait for ages in the car as he went in to various emporiums. Remember emporiums? Old-style, big shops that had lots of womens’ things and so forth; lovely old places, with wrought iron, things like that. There were his customers, and he’d forget about me as he sat inside having a cup of tea, entertaining the ladies by chatting to them, saying something funny. I don’t know. He was a quiet lad like that, and I liked him for that. It was nice. But don’t listen to me. What?

When did your father die?

RS: Back in ’86. He was born in eighteen-ninety-three; it was quite a good, long life. He had a van, which he fixed himself to make it higher. It was an old Jowett. Have you ever heard of the Jowett car?

I haven’t heard of the Jowett.

RS: Used to be a very popular car, once – and they made a lot of vans. My father got one of these vans and raised it; you know, he made it about eighteen inches higher, so he could hang his ladies’ frocks and coats and costumes in there, and walk into it. He did it all himself. He was quite a handy man, because what he really wanted to be was an engineer. But his father didn’t want him to be an engineer. And that’s why my father said to me, ‘Well you must be what you want to be, because I couldn’t be.’ What he wanted to do was build cars, like Ford. That was his dream in life, you know.

Did you begin your working life in a factory?

RS: The factory was De Havilland Aircraft Company, building chipmunks, at the time.

CL: Chip ‘n’ Dale, I remember them – they were great.

RS: Chip and Dale!

CL: They sang with very high voices, they were like the American alternative to Pinky ‘n’ Perky.

I hadn’t heard of the Chipmunk. The ignorance of comparative youth.

CL: And don’t forget you’ve got me who’ll do everything straight then lead you down some dark alley. Which again, you can read about in the Kent Messenger tomorrow.

RS: Are you doing that Ceri? That’s terrific – I didn’t know you were gonna do that, but there we are. Do you want me to ring – what’s his name – oh! His name is actually Chris Hunter. He’s the editor of the Kent Messenger. He’s a nice bloke, I like him. He’s been in touch with me a lot, to do this and do that. When Johnny Depp came here he only came for one day but someone had got hold of the idea that he was staying at our place in Kent – a week later there was a helicopter flying outside our bedroom window!

A week later?

RS: Yeah – he’d gone! But that’s what gossip’s about, isn’t it? I was so boring, of course, that he went within a day.

CL: You should have got a cardboard cut-out and kept putting it at the window. Then go up to it and strangle it occasionally.

RS: Yeah, absolutely. That would’ve been funny. But yes, I’ve told you about my father, and what he did. I liked his attitude to life; it was quite a good one.

We lived in Abergele, it was in the blitz, during the war, and we were living just near Wallasey. I was born in Wallasey, Cheshire – not far from The Beatles, actually, y’know, that’s where they were, and you perhaps can tell, sometimes, I can get that voice, because it was my original kind of voice. But Welsh as well, my mother was Welsh! And so I got that voice! A little bit of Welsh, a little bit of everything. And I did the best I could to be good, like my mother said I should.

I can’t stand mean-minded people, that’s all. I’ve seen it in life, I’ve seen a lot of it now, like those City bankers and all the rest of them. Filthy people. I mean now, for instance, I was thinking about the depression and everything, and the only people that still seem to be doing well are the moneylenders. I’ve done a drawing – it’s in the Statesman – called ‘The Debt Collectors’. The debt doesn’t go down. They only add to it. They are one member of society who does not change from what they are, which is usually greedy bastards.

Ralph when you say depression to you mean strictly financial depression?

RS: Financial depression, but depression as well – I think in a way our society is rather depressed, spiritually. I don’t think that people are happy as Larry and going through life as though nothing’s happening and everything is wonderful.

Is there anything we can do to guard against the potential for depression?

CL: Yes: Don’t go outside!

RS: I was outside this morning watching when somebody was putting straps on my pool cover. It needed re-doing. I’ve got a pool outside, I swam in it this morning. I swim in it every day.

CL: There’s no such thing as bad weather – only bad clothes.

RS: Yeah, that’s right, yes. Yes put that down, that’s really quite good. That’s the wisdom!

‘The wisdom’. Isn’t that how Hunter Thompson would normally try and finish up an article?

RS: No he’d finish an article saying Fuck you, Ralph. Like that, Ralph. The other thing was my name – he loved to say ‘Ralph’. If my name had been Trevor it wouldn’t have sounded as good.

You can bark the name Ralph in a way you can’t with Trevor.

RS: Trevor. It doesn’t work! Sounds a bit pansy-like, doesn’t it? Oh Trevor, hey Trevor, c’mere! It’d have changed his whole attitude to life, wouldn’t it? But Ralph. S’okay. Do that. That’s how he was. We got on well, pretty well right away. Back in 1970, we first met.

CL: Just to explain, Ralph swims every day. In his outdoor pool. Every morning, he starts the day off with a swim.

RS: I never miss a day, unless we go away somewhere. We went away last year to Forte Dei Marmi in Northern Italy, which is a place we first went to 22 years ago, now. We thought we’d go back there and see what it’s like. On our journey we met a lovely fella there; a German and his wife. They had a child who had a problem, a head problem. She was really quite infantile… her name was Dorothy. And ah… she … they looked after her, and they were wonderful with her. Each day in the pool, they’d be swimming with her, one either side of her, the father and the mother. They were wonderful people, really. We hoped to see them again. I don’t know if we’ll go, again, but I’d like to, go back to Forte Dei Marmi. There you go – you meet people and you think you’ll never see ’em again. It’s like saying hello to Ceri – I thought I’d never see him again. And then the next day, the first bird came through.

The story of the couple is touching. Rather than ask ‘who is the worst and most corrupt politician you have encountered—

RS: Well I think it has to be Bubbleface, doesn’t it?

CL: Nixon!

RS: What? No. I can think of a worse person than Nixon. At least he displayed his evil ways.

Who is Bubbleface?

RS: Cameron.

CL: But surely, technically, he’s not even a politician!

RS: No he’s not: he’s a City gent. And also born well, at Eton, all that stuff.

CL: He’s eaten at Eton.

Perhaps eaten children at Eton.

CL: Now there’s someone who probably would. ‘Get me somebody from the lower fourth in a sandwich, now.’

RS: Terrible! What a disgusting thought.

I actually didn’t mean to ask about the worst politician – I meant to ask about the kindest people or gesture that you’ve both encountered.

RS: I’ve just told you one – he was a doctor, y’know, looking after – they’d got this child and they’d decided themselves they wanted to bring her up. Not put her in some god-awful institution. And that, I felt, showed great kindness. I think Helger was his name. You’d be amazed how many things people do kindly, and not think anything of it. Not say ‘hey, guess what I did today, I did a very good thing.’

CL: People don’t take note of it. I’m saying this from experience, because I’m trying to think of the last time I saw a genuine act of kindness performed. Kindness should be performed in a random way, in a sense. I’ve seen a lot of conservationists work with kindness, trying to save species. I’ve seen vets trying to save beautiful birds of prey from having to be put down because they’ve been shot in the wing by hunters. Comforting giant birds of prey before they inject them to euthanize them. That’s really the kindness I’ve seen. Maybe it’s just living in the city, I’ve seen very little kindness these days when I wander around.

Ceri you previously told the story of being in Malta and seeing hunters shoot a bird through the wing. And although the bird wasn’t dying the vet had to euthanize.

CL: It’s a bird and it needs to fly. Without flight, it can’t adapt in the same sort of ways that perhaps we can if we lose a leg or an arm because we have a support structure. It’s a vicious world for wildlife. No other bird within its actual family is going to turn round and help. They’re going to probably wait for it to die and then eat it. So you can’t just go, ‘well we could keep it alive, we could…’

Yeah you could, but the amount of suffering because you’ve changed its fundamental existence… when you look at a bird flying, it’s a very different creature to when you see it land on the ground and try to walk around. They’re uncomfortable, they’re jaunty…

RS: They waddle around; they waddle, more than anything.

CL: They do all sorts of odd things, because they’re made to fly. I’m hoping that we can point out some of this terrible futility, this terrible pastime of hunting which goes on in this country in other forms – usually by the landed gentry and estate management of grouse moorland – whereby species and habitats are cultivated just to suit grouse-shooting. We’ve got big issues. I’m not just having a go at Malta – I’m having at loads of different places.

RS: Any place where people wear plus-fours and have a gun. They think it gives them a right to go ‘Raaraaa, let’s go on a hunting party! Jolly good, let’s do that!’

CL: That’s the whole thing that needs to change: we’re supposedly a people who move with the times – man in general – but actually people only move with the times if they’re told to, most of the time. There are people of certain elevation and status who will move with the times only if they so see fit. That’s just wrong to me.

Some of these hunting weekends can cost about thirty grand. There’s a great quote by Mark Avery, who used to be the conservation director of the RSPB. (He’s now left and he’s written Fighting for Birds.) It’s one great quote that sums it up, because we’re living in times where money controls. This line is: ‘We are often told that nature conservation is a luxury we cannot afford when it stands in the way of economic progress.’

This is the earth that feeds us all, that succours us all, that looks after us all, and yet we give very little back. Margaret Atwood told me that of all the money raised from charity – the percentages aren’t exact – but something like 96% goes to human causes while 2.5% goes to pets and domestic animals, and the other 1.5% goes to the natural world. Is it any wonder we’re completely fucked as a species, with that kind of logic?

RS: I’ll tell you what else you can do: Stop being empire-builders still, by going off to Afghanistan and ‘sorting out’ the people there by shooting them. That’s what happens. We get into that, we send an army out there to ‘deal with it’. And that usually means death, somewhere. That is a terrible thing. The fact that we’re in these places, I have no idea why – in Egypt and Syria and places like that – what the fuck’re we doing there? I don’t know.

I’d like to offer two ideas from different books. The first comes from your book Ralph – The Joke’s Over, your memoir. At the beginning you’re describing the Hunter Thompson’s monument, which ‘gathered its strength from some long-gone youthful spirit that wanted to wake up the world…’

This youthful spirit that wants to wake people up – to questions of conservation, or self-expression, or confidence or whatever it might be – does this spirit really feel long-gone?

RS: It depends what the youth is, really. I think there are a lot of youths out there who have got a voice but are not allowed to use it. I’m sure people out there care, even lots of young kids, but unfortunately a lot of them get in gangs and they get misled. They do silly things, stupid things. It often means destruction of some kind: smashing up somebody’s car, doing something like that. Or going joyriding. Things of that sort. They don’t have to do that but they do, for some peculiar reason. People think, ‘Oh it’s a boys thing, they do that when they’re young.’ They love taking somebody’s car and smashing it up somewhere, and leaving it and running like mad – they love to run – because they’ve got the energy to do it.

But there are so many people out there in the world. I’m not against humanity, per se. There are a lot of good people about. I’ve done bitter cartoons about corrupt people like Nixon, it doesn’t mean to say that’s what I feel about the whole society. If anything, I err on the kind side of life, if I can. It almost – well it does bring tears to my eyes – to see someone being particularly kind. It’s a wonderful expression of human nature when somebody is kind. Not saying ‘how much will you give me to be kind’, but just being kind. It’s a fantastic thing to be. We should think about things like that – the good side of human nature. I often think it with animals, for instance: I think gosh, those animals, they might have a dogfight or they might go out and kill something, but in the main, most things like dogs, particularly, are very nice and good. But they’ve been trained, in a way. The untrained animal doesn’t know that one day it will die. That’s another thing. I think, wow, that’s lucky. That you’ll die one day but you won’t know it.

Oh! I had a sheep, called Zeno. The Greek philosopher. I called him Zeno because I used to look into his right eye, and the pupil was square. I could never understand that. So I used to look into his eye for knowledge, for the day’s message. I wrote a song about it, saying ‘Zeno, you are a sheep of certain wisdom… what I need to know you can provide. Whether it’s the answer to a problem, or a fear that troubles you inside…’

Ze-no, oh Ze-no, you’re so wooll-ee!

CL: I love it! Where’s Zeno now?

RS: I’m afraid he’s gone to meet his maker.

CL: To the great casserole in the sky.

In relation to the youthful spirit, Ceri mentioned that working on Extinct Boids forced him to ‘de-learn’ and reconnect with the natural world in a way he hadn’t since he was young.

RS: Before Ceri and I eventually made the book, I didn’t realise how much I do actually look out the kitchen window to see a bird and think, ‘ooh, what’s he doing?’ Just the nature of what they do. That, I suddenly found, one is naturally curious about. You watch the behaviour pattern. You’re not looking for theatre.

I have seen that, though. I once got some ducklings and their mother and brought them back, some years ago. What a lovely idea, ducklings in the yard. We’ve got five acres so may as well do something with it. I watched them, the mother waddling and the babies waddling behind her, nine of ’em. Such a wonderful scene. And do you know, a moment later a fox came and rrripped through them within seconds. And killed them all, yes. Just like that: ssshhhew.

It was a shock to me. I’ve never really wanted to keep anything since. I had a dog, called Flop and she used to herd the sheep that were in the back yard. We had a flock of sheep – a local farmer came and asked could he put them in the yard, in the back, the orchard. Then he took them away, and I suppose he had them killed. But that was not my business. He gave me this sheep, which was Zeno, because I liked the look of it. It had somehow managed to grow quite large. He was huge!

CL: But you can’t have had the only sheep with rectangle eyes.

RS: No there must be more! Yes, they probably have – well, you know – I talk a load of claptrap. I never check my facts. That’s another thing: never check your facts.

CL: I’m going to look it up. It says goats have rectangular pupils.

RS: Yes, ah yes, I had a goat, too! I had a goat called Rebecca.

CL: Here we go: ‘Why sheep, goats, octopuses and toads have rectangular pupils’:

‘The reason these animals have rectangular pupils is because this is what helps them avoid predators. Rectangular pupils tend to get very narrow during the daytime, which give animals a greater accuracy and depth perception in their peripheral vision. Traditionally seen as prey, thanks to their eyes, these animals are able to avoid predators.’

RS: Ah. But I’ll tell you what it’s like – it’s a bit like going to the pictures, isn’t it! The vision you get is a rectangular screen. That’s the shape of the eye of a sheep and a goat and whatever else.

CL: So it’s perfectly suitable to take those animals to the cinema. We need more sheep, goat, octopi and toad cinemas.

RS: I see, yes. Listen now Ceri, we’re supposed to be speaking wisdom, now. Not silly ideas about parrots in fridges and the back seat of the pictures on a Saturday night!

The second quotation, by way of closing, came to mind with the mention of Kurt Vonnegut. In Breakfast of Champions Vonnegut introduces himself, the author, into the world of the fictional characters, and sets them free, in a sense.

RS: I think it’s very kind of you to leave us with a rather ominous reminder of mortality.

Well the focus is Extinct Boids and we’ve talked to some extent about death and extinction, so it seems morose but fitting. When the fictional character Kilgore Trout meets his maker Kurt Vonnegut, it says: ‘Here was what Kilgore Trout cried out to me in my father’s voice: “Make me young, make me young, make me young!”’

RS: Yeah. You think that I don’t say that every day?

CL: But as you get older you realise that young is a state of mind. I am still as imbecilic as I was at the age of nine, and the same things still apply to me, the same things still excite me, plus a few others. I just think none of it means anything! You just get on with it, and then you don’t.

There’s only two ways of doing things: doing them and not doing them. Make me young? As long as you still want to be young you will be young. That’s the thing about trying to be young as you get older: you can be young mentally, but once you start trying to hang out in the same clubs, wear the same clothes, do the same things with your hair… then you’ve actually become very old. I think the only way you can ever do it is mentally. And that’s the most important lesson I’ve learned: Never to let that go.

RS: Yes, you’re a very… optimistic person – I see that. And really, it puts me in the shade. Because I feel far more ominously – far more threatened by life, than that. I really am. I’m scared shitless by it all.

CL: I have to be! I’ve had cancer twice, a heart attack and a strangulated hernia, all of which have nearly killed me in the last twelve or fifteen years. But it’s never changed my outlook.

RS: Don’t get me wrong – you’re amazing—

Really Ceri? I had no idea.

CL: There you go – the things you find out with the last question of the day! But people say, ‘does that change you?’ No, not really. It just reaffirms everything I believe in, which is just do what pleases you and what you need to do, because we sure as hell all need to do something. That’s all I know. That’s the only way I can deal with it all.

RS: I’m obviously… I must be a lazy—

CL: You say that and you’re so not lazy!

I agree, Ralph I think you’re being immodest, slightly. I think people look at you and see a productive, confident, assertive and somewhat fulfilled character.

RS: I am using my false modesty! Haha. We’ve just been gabbling through a whole load of nonsense, haven’t we? I’m sorry about that.

I think we’ve had an illuminating conversation…

RS: You could probably go sit in the House of Commons in a couple of days. Just try and sound Welsh. ‘Hallo boys!’ They’d suddenly have a fit. Anybody Irish… Well – except for – oh, god I’ve forgotten his bloody name now. Who was the awful, rather rumbustious man?

Are you thinking of the Reverend Ian Paisley?

RS: Ian Paisley, that’s him! Yeah. You’ve got it.

Didn’t you once illustrate Ian Paisley as a massively-winged fly descending on a pile of steaming faeces?

RS: I did indeed – you’ve got that one have you? God. In the same picture there’s Enoch Powell, as a fly. They’re sitting on shit, that’s what they’re doing. They’re alighting on shit. And what’s his name – oh god, come on, the bloody memory, that’s what goes – the Prime Minister, Edward Heath! He’s tip-toeing with a fly-swat. I think I did that for The Times.

In terms of an English national character, as somebody, Ralph, who has depicted the corruption, depravity and immorality of politicians and extremists—

RS: And businessmen.

I was going to say bigots, but businessmen—

RS: They go hand in hand. They’re one and the same.

Is there a streak in the common character that makes one child end up as an Enoch Powell and another end up as a Ralph Steadman?

RS: I think, with a lot of people, it’s the possibility of making money. Immorally or whatever way, they can make money. Even if they have to use someone else to do the dirty work. That appeals to a lot of people. I think estate agents do that. There are a lot of people in that category. People that start superstores and the like, really, in a way, are just greedy bastards who know how to get round certain limitations and suddenly make a killing.

Early in our conversation you described yourself as a corrupting influence.

RS: Yes. I go round smacking old ladies!

CL: You should see what he does when he holds them down.

Is money a bigger corrupting influence than you are?

RS: Money’s only contribution is when somebody desperately needs it, to help, to buy food or whatever, or a roof over their head. But doing drawings because what you want to do is do good in the world, which is what I thought I was going to do when I started cartooning…

I thought the world would change. And I was right, it has changed, but it has changed for the worse. That’s the shame of it. All my idealistic ideas, early boyhood ideas about changing the world have really come to nought. Nothing. That’s the only disappointment I have. I really mean that. It’s hard. It’s a shame.

But given that we have good books like Extinct Boids produced by you and Ceri, do you really think the world is worse off with your efforts than it might have been without?

RS: Well maybe there you’ve got a point. It might have been better off. If the world is to be better off it had better sell more copies!

CL: A third of the share of the profits goes towards conservation, which is really great. But like all these things, you just want more to go to the cause. That’s what we’re really trying to do. Just bring new people to a difficult subject: extinction is going on every day. There’s an awful lot of accelerated extinction because of what we are doing to this planet.

When you’re trying to show people something, the greatest thing you can ever see is them turning round and for you to hear the initial words ‘I had no idea.’ Because it means suddenly they do have an idea, and maybe – just maybe – you’ve pricked their interest enough for them to do something about it.

If there is a small gesture that many people can make to increase awareness of the natural world, of conservation, to improve things for birds, to change the world even, what could it be?

RS: Do you mean hospitals and the like?

Hospitals are a different issue, but—

RS: Well the National Health Service is going down the pan. I did something at Christmas for Save the Children and another group. They were giving me £300 for something and another person £200, so I said, well that goes to St Martin-in-the-Fields.

There’s a Reverend Sam Wells, who runs the St Martin-in-the-Field Church, and helps the homeless people and things. I got the money, to do things like that. If you ever get money that comes easily – and this did come easily – give it away. I do.

There’s almost too much to talk about and to dig in to.

RS: Well if there’s something you forget, if you need to ring me as you’re writing or arranging or organising your gabble that you’ve had from us, ring up.

‘Can you clarify… did you say ‘bird’? Or did you say ‘boid?’ As it stands, we have more than two hours of conversation.

RS: Oh my god!

CL: That’s your fault, for asking all these damn questions!

RS: You know, my wife Anna said, ‘That’s a stupid thing to call a bird.’ And she’s got a degree in English. I’ve only got an honorary degree. I don’t have a proper one.

Extinct Boids by Ceri Levy and Ralph Steadman is out now, published by Bloomsbury

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more