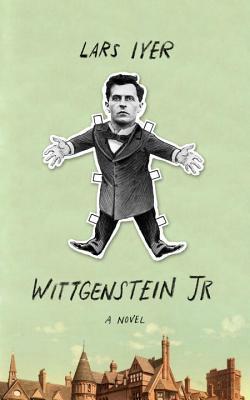

‘Literature is a corpse and cold at that.’ Lars Iyer says in his ‘literary manifesto after the end of literature and manifestos’, a title which perfectly captures the spirit of his work — a playfulness around and downright contempt for topics often considered to be the most serious of all. We’re all doomed and that’s what makes it all so funny. His new book Wittgenstein Jr is his first ‘novel’ following his trilogy — Spurious, Dogma and Exodus — which all began life as a blog, detailing the conversations between a fictionalised version of himself and his friend W. (Will Large another philosopher and Blanchot scholar). Sometimes thought-provoking, often hilarious and almost always insulting, their ruminations on death, philosophy, rats and idiocy made the apocalypse more fun than it has been in a long time and Wittgenstein Jr is no different.

The novel centres on the relationship between a group of Cambridge students and their professor who they have taken to calling Wittgenstein. A cast of archetypes that provide a chorus of voices to confound and infuriate their mentor, the student’s don’t seem able to ‘get’ Wittgenstein’s classes. Nor does he want them to. Written in Iyer’s now unmistakable musical prose Wittgenstein Jr provides a wonderful character study of one of the greatest philosophers of modern times, a hilarious take on modern life inside academia, a set of profane t-shirt slogans and a whole lot more besides.

Simply: why Wittgenstein? What is it about him, aside from his being another W, which made him the best vessel for you when writing the book?

Lars Iyer: I like to write of philosophers. What a glorious subject philosophy is! And how difficult! ‘How can a man be a philosopher?’, E. M. Cioran asks. ‘How can he have the effrontery to contend with time, with beauty, with God, and the rest?’ It’s a good question!

Real philosophers are only ever would-be philosophers. They are always worried that they are a sham. They feel a sense of vocation, but are not sure what they are being called to. They’re restless. They never feel they’ve arrived. They feel the need to start over, to make a fresh beginning, a fresh assault on the old problems. But they also have a burning sense of the importance of their topic. This does not mean they’re blinkered. Philosophers also have a sense of their times, and (very frequently) of being against their times. They’re diagnosticians, symptamologists. They’re working on a cure. They philosophise for the world, even if the world ignores them. It’s admirable, but also quixotic.

There are few philosophers who felt the duty of philosophy more strongly than the historical Wittgenstein (1889-1951). My Wittgenstein – a philosophy lecturer in present-day Cambridge – has similar fervour and ambition.

The lack of characterisation of the students in the novel feels very deliberate, and I wanted to ask you about why that is? Do they function in the manner of a ‘Greek chorus’, is their ‘flatness’ for want of a better word a reflection of their subjection to the pedagogy of Cambridge, or is it something else?

LI: There are many elements to my student characters. I wrote the ‘serious’ parts of my novel first – pretty much everything my character Wittgenstein says. In my mind, I wanted to my novel to be austere, spare, and mysterious, like Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, or Will Oldham’s Joya. But my novel lacked life – a real crime! It lacked levels. It wasn’t entertaining. I found myself in Dublin for the day, with nothing to do. I wandered into a cinema, where they were showing Almodovar’s I’m So Excited, a wonderful film, a variation on the airplane disaster films of the ‘70s. Each of his characters has an intriguing backstory, revealed through a little vignette. It occurred to me to focus on each of my student characters in turn, in a light way, an entertaining way. Of course, the disaster in my novel was that of a character, similar in temperament to the real Wittgenstein, coming into collision with contemporary Cambridge University.

Your previous trilogy of books — Spurious, Dogma and Exodus began life as a blog, and so Wittgenstein Jr is in some sense your first novel. What made you decide to revert to this more traditional form?

LI: The previous novels only began life as a blog. Blogging let me discover the two characters and the distinctive narrative voice appropriate to explore their relationship, it is true. But it was only after I abandoned blogging in my old style, and began to use my blog as a compositional tool, that I wrote my novels. As soon as you subordinate blogging to greater end, you’re no longer blogging, not really …!

Those three books are very much concerned with the notion of friendship, I wonder if you would talk a little about how your conception of how friendship relates to the relationship between teacher and pupil?

LI: All my novels are about friendships between philosophers (would-be philosophers). The Greek word for friendship, philein, is right there in the original meaning of the word philosophy itself. Philosophia – the love of wisdom. In my novels, friendships between philosophers (or would-be philosophers) have a ‘third term’: W. and Lars, like Wittgenstein and his students, are also friends of wisdom itself. In both cases, it is a matter of a personal friendship in which something philosophical is at stake.

It is on this model that we might understand the relationship between teacher and pupil. Both, if it is a genuine relationship, have a relationship to philosophy – and to themselves as philosophers (as would-be philosophers). Both feel a sense of vocation, and are trying to respond to this call. In this matter, the teacher can help the pupil by his or her example, showing how to avoid pitfalls. There is the danger, for example, that the pupil will relate to the teacher as an authority rather than as a fellow seeker-after-wisdom. This is what so frustrates Nietzsche’s fictional character Zarathustra. He is always demanding that his followers leave him alone and follow their own path!

Walking is another constant theme in your books, yet the walking always appears to be circular, dislocated, un-geographic almost. Is walking, physical motion, something you consider to be intrinsically connected to writing, to thought? Is the walking which Wittgenstein does any more purposeful than that of Lars and W?

LI: Socrates gives an unforgettable image of the philosopher in Plato’s Symposiuim.

The philosopher is the son of the goddess Poverty and the god Plenitude. Like his mother, he lives in want. But he has from his father, a sense of the good and the beautiful… The philosopher, neither rich nor poor, neither wise nor ignorant, wanders in search of something. And the philosopher does so on foot…

W. and Lars walk a great deal. W. seems to value a kind of integrity in walking. It is, for him, an act of exodus. A way of leaving the all-too-compromised university behind. Lars, who is constitutionally intolerant of academia, is always ahead of W. Of course, W. suspects that Lars is simply leading him in circles…

Is Wittgenstein walking in circles? His Cambridge walks seem to fill him with horror. The new buildings, encroaching on the older spaces of the town! Commercial Cambridge, with trashy buildings which might as well have been ordered from catalogues! Wittgenstein seeks a kind of internal exile. At the same time, he feels that there’s something for him to confront in Cambridge – and his walking is part of this confrontation.

I was reminded of O.K. Bouwsma’s book, Wittgenstein Conversations 1949-1951

LI: Yes. I am indebted to Bouwsma’s memoir, and all the others…

This sense of motion is reflected in the discursive and musical qualities of your prose. Do you see a kind of unity between that circularity of motion and music as being central to your work? Are you writing in Werckmeister temperament?

LI: In the end, the Spurious trilogy moves in circles – smaller circles and larger ones. Peculiar circles in which nothing really begins and nothing really ends. There is more apparent linearity in Wittgenstein Jr, but really it is the same movement as previously – from chaos to (apparent) order and back to chaos again. The circle is larger, that’s all.

Humour and lightness too seem to be central to your concept of literature. Is this a result of the fact that the only literature we can produce is a pantomime or, as Mulberry says, a parody of a parody?

LI: A personal confession: I crave lightness. There is a terrible heaviness abroad in our world today. There’s a lack of lightness, of joy, of laughter. Oh, everyone speaks as though they’re joyful – they use the most hyperbolic language, lovely this, lovely that, but they don’t seem to feel this supposed loveliness. Their faces don’t show it. Their gestures.

I think this is part of a total pragmatism that has spread everywhere. The obsession with managing, with problem-solving. We carry it home from work. We administer our lives, our relationships with others. We manage our lovers, our children, our friends. The result: joy becomes satisfaction with a problem solved. Sadness becomes mere dissatisfaction at a problem unsolved.

Bureaucracy has spread to every corner of our lives, and exacts a terrible price. First of all, we have no ambition for our lives. No instinct for greatness. No sense of yearning – of straining after something. There’s no urgent sense that life is finite, that we can be more than who we are. There’s no sense we are missing something. That we have to struggle with life.

And, secondly, there’s no lightness. No fleetness. No swift-footedness. No gratuitousness. No generosity of spirit. No open hearts. And no laughter – I miss laughter.

I think our duty in company is to liven things up. Not just after a bottle of wine on Saturday night, but on Sunday morning, too. Save us from stolidness! And I think lightness is a duty of literature, too, and not just because it has become pantomime or parody, if it has indeed become pantomime or parody…

In Nude in Your Hot Tub… you talk about art as being subsumed into the cultural apparatus. Is there any way now for art to be oppositional? Is, as Kertesz said, ‘bearing witness’ sufficient to avoid the descent into kitsch?

LI: Art versus culture? Eric Hobsbawn has recently retold the familiar story. The modernist arts did not serve. They were insolent. They thumbed their nose at bourgeois tastes. Back then, it was possible to talk of culture in an evaluative sense. Art had taken the place of religion – it was appropriate lofty, it led to spiritual advancement; it was the object of devotion. And it was rigorously distinguished from ‘lower’ forms, from mere ‘entertainment’, from everyday life. There are still artistic experiences of this kind – the Bayreuth festival, for example. Salzburg. But they are not typical. The distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ have collapsed. The old sense of culture collapsed long ago. We are obliged to use the word, culture, descriptively now. But that means the old sense of art as rebellion has lost all meaning. What do you rebel against? The old-style bourgeoisie have disappeared. There’s no one to shock. There are subcultures, microcultures. There’s a place for everyone.

We could rebel against the market, I suppose. Against commercialism. Against the elevation of monetary value above all else. We could rail against capitalism. But it’s precisely the market that makes room for us all – for niche-markets and boutique-markets, for subcultures and micro cultures.

The war-cry of modernism: make it new! How to make it new in our times – to witness our times and respond? I wonder whether it is even possible. A kitschified realism mirrors the old stabilities, an older world, now disappearing. A kitschified modernism mirrors the old instabilities, the cracks in the old bowl of culture. But the bowl has shattered… So what does that mean for our arts? What would a genuine post-modernism look like? Can there be such thing?

In a space where even the death of literature has become kitsch, and the only thing to write is its epilogue, is the only way forward something akin to Houellecquian nihilism, a rejection of life and a wilful, selfish subsumption into the mundane and individual pleasure?

LI: Kitsch is a sentimentalism – it evokes stock moods, generic emotions. Kitsch supports our beliefs, it doesn’t question them. It seeks to satisfy our needs, instead of creating new ones. Kitsch is stereotypical. It depends upon universal images, common denominators. Kitsch is realist in the sense that it represents the world according to standard systems of representation. Kitsch complies.

Kitsch, as such, is the opposite of modernism. It cries, make it old!, instead of, make it new! Diagnoses of the death of literature are old news. We’ve heard it before. There’s a dying breed of cultural pessimist, which mourns for a lost world of old culture, for the time when Art and Literature were taken seriously. But there’s another kind of cultural pessimist, who mourns for the lost modernist energies that depended on the old cultural world as a kind of foil. We know better now, we might respond. We’re pluralists! Culture is not an evaluative term, but a descriptive one! There are many cultures – subcultures, microcultures – thank goodness! Let a thousand flowers bloom!

But this response forgets the circuit which used to run between the energies in question and culture at large. It forgets the way in which mainstream kitsch could be challenged. There was something at stake in modernism, in making it new. Despite our pluralism (and perhaps, in part, because of it), the mainstream still exists. Sure, there are pockets of experimentalism here and there, small niches, often protected by the academy, but they do not impact on the mainstream.

The modernists shattered the vessels, they shattered older, kitschy forms. What should we do? Are there more vessels to shatter? Show we try to break received forms all over again? Or is the idea of ‘breaking received forms’ a kind of cliché? Is anyone mourning the end of vanguardism, of modernism, the eternal promise to make things new? Does anyone care – really care – about the old genres? Is the idea of the ‘death of literature’ itself a kind of kitsch?

However we might address such questions, I don’t think the answer is ‘Houellebecquian nihilism’. Even Houellebecq isn’t a nihilist – there is a sense of utopia in some of his writings – a sense of the possibility of friendship and love. Houellebecq’s writings are full of hatred. They’re troubling. They’re raw. They’re symptomatic. He exposes kinds of negativity which we are too quick to disavow. But there is a kind of hope, too.

That’s from Atomised. Does it read like nihilism to you?

Wittgenstein Jr is out now, published by Melville House UK