Some books ask that you take them seriously, erasing everything comic, positioning themselves above the world. Others seek to make you laugh, erasing everything serious, positioning themselves beneath the world. There is a third category, much rarer. These books operate in a space where such distinctions are no longer possible: from an anxious—not a golden—middle. Where the laughable and the serious remain, mutually protecting one another; where they do not merge and yet are impossible to distinguish. We laugh, but that laughter remains caught in our throat. Such books are deadly serious.

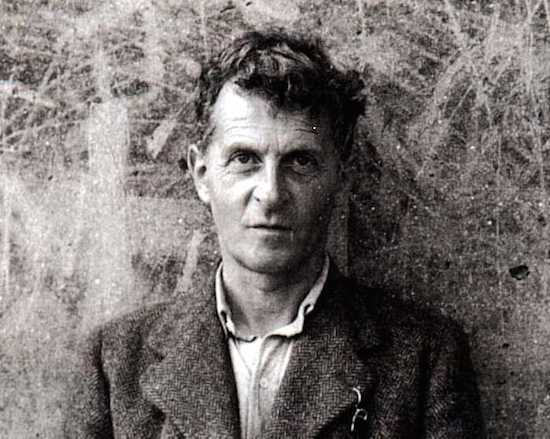

Cambridge philosopher Wittgenstein Jr. doesn’t look much like -Sr. He’s fat, for a start. Whereas his namesake was small, he is tall. And his speech betrays almost no trace of an accent. “But he has a Wittgensteinian aura,” agree the students who name him. “He is Wittgensteinisch, in some way.”

Like his predecessor Wittgenstein is severe, prone to alienate and to entice students with gnomic wisdom.

Within a few weeks his class shrinks from forty-five to twelve; those who remain do so with bafflement and dedication in equal measure. The novel’s action concerns the relationships that form between the students and their lecturer. It is like the traditional campus narrative in that an intense academic environment is offset through a regime of drinking, drug-taking and one night stands. It is unlike the traditional campus narrative in almost every other respect.

The students are sketched lightly and impressionistically; they’re sounding boards off which Wittgenstein’s speculations and lamentations can echo. There’s Mulberry, the death-obsessed hedonist; Titmuss, the homily-prone gap-year returnee; the Kirwin twins, the effusively healthy and moneyed blonde Bestien; Ede, the self-hating rich kid. And then there is Peters, the book’s narrator, quiet and sensitive we learn through his coy reportage of the opinions of others; modest, we assume, through the modesty of the information we learn about him.

If the characters sound somewhat clichéd there would seem to be some wider point to this. Even if we are mostly copies of copies, even if the master tapes have gone missing, even if we have forgotten they ever existed, something important remains. It’s that which remains, whatever it is, that makes us still care about Iyer’s creations, even while they wear their hackneyed unoriginality so openly on their sleeves.

Wittgenstein and his students mourn philosophy’s absence. For the students that mourning remains melancholic. The interminability of philosophy doesn’t propel them further into it; rather, it gives them the sinking sense of having arrived too late. They despair, mostly, at their inability to despair. “The Kirwins’ tragedy”, we read, “is that there’s no war for them to die in. … No chance of glory, no heroism.” “To come after something, and before nothing: that’s our condition, he says. To have come too late, and not really to know it.”

The students long to be part of the game of thinking. But in always seeing it as a game they can never step onto the pitch, are destined to remain cheering from the sidelines. At one point they agree: “We like the romance of having our very own thinker.” Tellingly, they act out the deaths of their philosophical idols, martyrs to Serious Thought. The trajectory reveals a kind of reverse teleology: from Socrates, heroically in possession of his death; to Nietzsche’s protracted dying; to Empedocles, subject of Hölderlin’s thrice-written, unfinishable masterpiece. Of course their problem isn’t simply one of ending; they can’t even begin.

Wittgenstein on the other hand is very committed; he seeks to close the gap between life and thought, at no cost to either. What he seeks has the purity of logic and the vitality of life. He is confronted with an impossible demand, but he is without the patience to see it through its interminability, or the impatience to bring it to a conclusion. “Naturally, he is suspicious of impatience, he says. But he is wary, also, of patience”. He wants to—somehow, impossibly—live this demand, in its impossibility, at once. As the novel progresses he becomes seduced by the messianic promise of an end to philosophy, a prelapsarian state where we would be undivided from ourselves. Of course it is his book that will inaugurate the messianic age.

Iyer succeeds in treating these issues with a lightness of touch; with the pathos of tragedy and the bathos of farce, without resting in either. Ultimately something remains amongst the ruins. Something irrepressible that can’t be erased. The students’ endless bemoaning of having arrived too late may appear a lot like cynicism, and it is; but it isn’t simply that. There is something communal to their disappointment, something shared. Perhaps its name is friendship: the confraternity of those who can’t find anything larger to tie themselves to and yet who, in their restless yearning, are brought together. A curious take on the Nietzschean idea that the friends have “a shared higher thirst for an ideal above them.” Indeed it won’t come as a surprise (though maybe as a relief) to readers familiar with his trilogy, that Iyer’s is not an ordinary campus novel in which the students learn something from the success and the failure of their lecturer. Iyer’s is not a parable. The characters themselves don’t really develop at all; it is that which binds them together—friendship, disappointment—which grows. It is this, the apparent background to the novel’s action, that shines through.

An aesthetic is emerging from Iyer’s work over the last few years, one that’s surprisingly consistent: rigorously anti-beautifying, anti-kitsch and yet, for all its cynicism, quietly optimistic.

Readers of his trilogy will find that Iyer’s style remains largely unchanged. For the most part this is welcome, though I wonder if a less fragmented approach might have worked better when treating the character of Wittgenstein. If Bernhard’s magic works by a sheer accumulation of terms—opacity exuding from an excessive paroxystic communicativeness; words piling up until the unspoken rears its head—Iyer’s disrupting of Wittgenstein’s monologues at key moments sometimes has a deflationary effect, can give them the finality of a well told joke.

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being Kundera famously defines kitsch as the “denial of shit”. But literature has become comfortable with the abject; shit no longer poses any problem. Literature can name shit, describe it, make it the theme of an entire story. What literature remains uncomfortable with is the prosaic, the mocking banalities of everyday life. With proper names. Ede and Peters spot Wittgenstein, shopping bags in hand.

ME: Scones, so far as I could see.

EDE: So, genius eats scones.

Iyer, in his “literary manifesto after the end of Literature and Manifestos”: “Write about this world, whatever else you’re writing about, a world dominated by dead dreams.” To represent the Serious unburdened by the embarrassing realities of the modern world, to deny Sainsbury’s, he seems to be saying, is kitsch. Thus, without shortcuts, he tries to show not only what is lost in the modern world, but what remains—what his characters retain even through their despair, because of their despair, even if they don’t know it. One might call it hope, though it is probably Kafka’s hope.

Wittgenstein Jr walks a line between cynicism and optimism, between the laughable and the serious; it’s a line too fine to be easily called. Whether it fall down on one side, or remains in the anxious middle, will depend on how much the book makes you laugh, and what kind of laughter that is. I, for my part, found it hilarious.

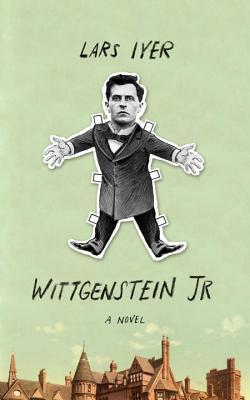

Wittgenstein Jr is out now, published by Melville House UK