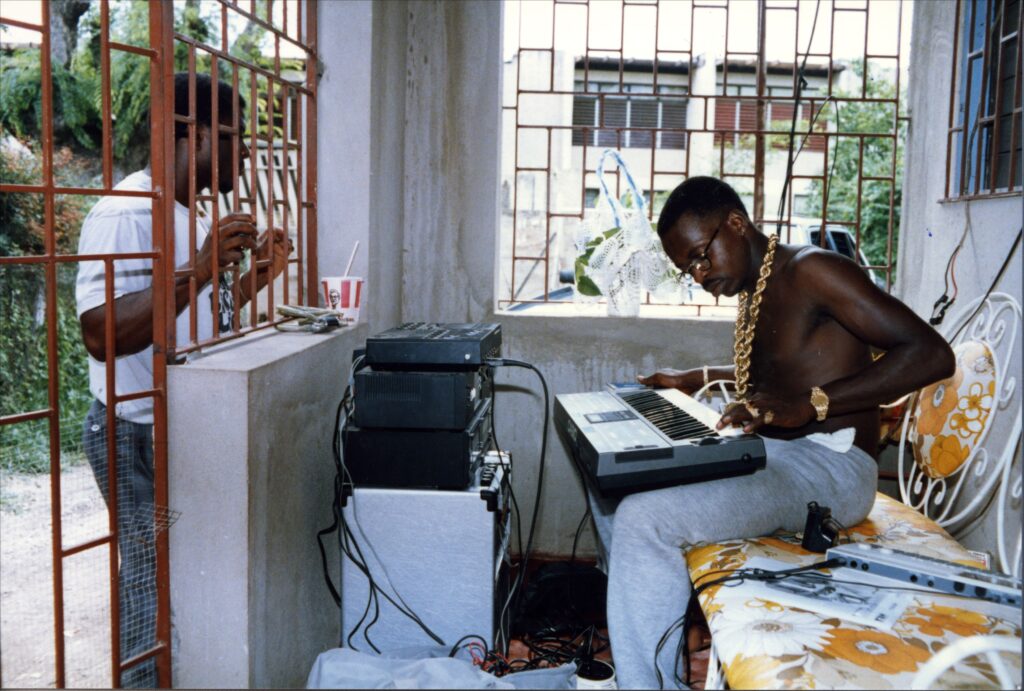

Dancehall star Tiger composes at home.

(Photograph copyright Beth Lesser. Courtesy of Soul Jazz Records Publishing.)

It’s easy in retrospect to be critical about the kind of reggae that finally got taken seriously by the UK rock press in the late 70s. Reggae had been popular in the UK since the 60s with pop crowds and young working class city dwellers of black and white but it was ‘serious’ sufferation of artists like Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Steel Pulse that was made more palatable to the ears of Eric Clapton and Procul Harem fans by a syrupy Island Records patented de-Jamaicafication process. As always the beard scratchers and self-proclaimed intelligent music fans were the last to get to the party.

It’s also easy to sense the patronising attitude to black artists, that didn’t want to acknowledge any of the ribald fun of reggae culture and it’s entirely possible that this helped popularize the altogether less heavy (sonically and lyrically) dancehall music, which had its imperial phase during the late 70s and 80s. The genre was a loose one at first literally meaning music that was designed to be played in dancehalls with upbeat tempos and walking basslines that were ideal for dancing rather than ganja infused introspection.

As is often the case the real sonic leap forward happened almost accidentally with the growing use of cheap store bought synthesizers and drum machines to replace expensive session musicians in the 80s. The basic set up only allowed for a simpler, harsher riddim (best experienced through the medium of chest collapsing bass bins), probably first exemplified by ‘Sensi Addict’ by Prince Horace Ferguson, but it really only came to prominence with Wayne Smith’s still fresh sounding ‘(Under Me) Sleng Teng’; a jolly tale of hiding one’s ganja under one’s voluminous rasta hat when representatives of the local constabulary make an unexpected house call. The harsh rock & roll aping digital backline proved such a hit, it changed the face of Jamaican music for good.

Of course, things haven’t changed that much and it is uncomfortable to note that music from the West Indies still needs to go through some kind of quarrantine period before becoming acceptable by a mainstream audience over here. At the same time however, there is nothing wrong with revisiting old genres and while waiting for the reggaeton revival in 2025, you can get maximum enjoyment re-immersing (or simply immersing) yourself in dancehall.

Two of our favourite things last year were Soul Jazz’s Dancehall compilation and the accompanying book; here we talk to Beth Lesser the author who regularly reported on the scene for Reggae Quarterly but who now lives in Canada. (At the end of the interview is a gallery of her excellent photographs taken from the book.)

In general terms is dancehall just another term for Jamaican pop music that was most prevalent in the late 70s and early 80s right through to the 00s, in the same way that ska, rocksteady and reggae were other terms of this nature?

"No, not exactly. Ska and rocksteady were followed by rockers and all three terms refer to the beat. At first, dancehall just meant the kind of music played in dance hall sessions- which includes all Jamaican pop music. All of it was played in dances. That was how it was consumed. However, now people are using the term dancehall to refer to the digital music that emerged after 1985.

This said, are there any defining sonic or lyrical qualities that mark out dancehall as far as you’re concerned?

"Jamaican music was being called dancehall throughout the 80s, before the common use of drum machines etc. To People who heard the loosely used term, it meant a higher portion of dancehall style deejays (meaning they perform spontaneously rather than sticking to written lyrics) and sing jay style singers – or anyone who performed regularly in the dance or whose music was played in the dance. The sing jay singing style was marked by chanted parts of the song or a more restricted melodic range that emphasized the rhythm – closer to what a deejay does. The deejays left their lyrics open to respond to what was going on in the session – who was there, which ‘posses’, how they were dancing etc – and what was going in the neighborhood, in the country. Yes, the use of slackness and violence do set dancehall apart from the more polished soul styles but DH can contain an infinity of other types of content as well, from romance to reality and, of course, roots."

I suppose in the UK the popular consciousness of dancehall lyricism is that of the ‘slack’ lyric, be it casual or violent homophobia, graphic sexuality or gun play. Is this the full picture though? What are the lyrical concerns of dancehall and how do they compare to the lyrical concerns of roots reggae, for example? Was Jamaican culture going through wider changes as exemplified by the regime change from Michael Manley’s PNP government to Edward Seaga’s right wing administration?

"With Seaga in power, after a landside in the 1980 elections, the political violence subsided and the economy improved so people were able to get on with their lives. They could move more freely, and previously scarce goods began to be available again. Seaga, who was backed by the then current US administration of Ronald Reagan, was able to get the support that had been withheld from Michael Manley, a man considered by the US to be a danger to North American because of his socialist ties.

"With the economic upturn, the lyrics began to move away from the heavy political; and spiritual themes to lyrics that where humorous, topical or just plain fun."

The Jamaican recording industry is notoriously anarchic – was it difficult to track down and interview certain people for the book?

"Not really. A lot of the people I interviewed, I already knew well from my years of traveling there to do the Reggae Quarterly magazine. And my husband did a radio show, so he had a lot of the people there as guests when they came to town. It was also a bit easier than before actually with the internet and cell phones. That said, there are still some people I’m looking for, mainly people who lived here in Toronto and I would love to see again.

But as to the first part of the question, yes the business is completely unpredictable so you just ‘go with the flow’ and take whatever comes your way. You never know who is going to give you a good interview in advance anyway, so you just have to go into it with an open mind."

The book comes with amazing photographs – where did they come from? Do you see dancehall as being similar to other working class youth cults that fetishized dressing up at weekend dances, such as the mods in the UK and jazz fans in the US?

"I took all the photos, in various parts of Kingston.

No it’s not like that culture. It seems to me (I grew up in NY where things are different so may be I don’t know what I’m talking about) that those youths feel they have dull lives and boring jobs and they go out and try to be someone special on Friday and Saturday. Jamaica doesn’t have a Working class youth culture.

The youth in the ghetto are unemployed and dress to imitate the gangs- they lead the way for fashion- like the Spanglers. If you can afford these clothes and you live in the ghetto, you must be doing something that people ought to (or better be) respecting you for. People with a low ranking, or just ordinary youth, didn’t dress up in the styles of the big gangs. They dressed nicely, clean cut, but not showy."

In Jamaica stars like Eek-A-Mouse and Yellowman easily rivaled the popularity of Bob Marley, is it easy to explain why they made less of an impact in the US or UK?

"Because white people were buying reggae abroad. And they couldn’t get their heads around the fundamental contradictions of someone like Yellowman who could chat slackness and Rastafarian lyrics on the same LP. And they couldn’t understand the words. A lot of people from outside Jamaica just saw slackness as juvenile. The type of people who listened to reggae tended to be white, upper class, open-minded, liberal and they saw slackness as misogynist and adolescent. It had no message (as opposed to the music of Bob Marley). It gave you nothing to ‘think about’, nothing to strive for. Dancehall in the early 80s was still very ethnically Jamaican. It hadn’t become cross over music yet."

Dancehall threw up many female stars such as Sister Nancy and Lady Saw, was this the sign of a shift in attitudes or was the JA music industry still as much of a male preserve as it always had been?

"I think ( hope) it is changing. Women really got a beating in the 80s with all the anti-female lyrics calling women "pancoots" and "tegeregs". Women were ‘allowed’ to be singers – that was OK but when they started to become DJs, they got a lot of resistance with people saying they were no good. That started to change in the 80s – but, you still saw no women in other areas like sound owners or selectors. I hear that’s better now but I don’t follow the music like before."

Digital dancehall, conversely, is very easy to define as a ‘new sound’. The new sonic textures achieved by using cheap store bought synthesizers and drum machines became wildly popular with the public. How important is the aspect of sonic novelty in Jamaican pop music?

"Not as important as it has been in North American pop music (where the Millie Small ‘My Boy Lollipop’ was a hit). Although, I do think that it contributed to the success of ‘Sleng Teng’. I think Jamaicans respond to sound differently and reggae had a different relationship with sound than American pop music which was originally engineered to sound good on a transistor radio. Reggae was always engineered top sound good outside at high volume (at a dance)."

Was there an extent to which dancehall was less politicized because it had actually become dangerous to be publicly politically affiliated?

"It was dangerous to be politically affiliated but that didn’t affect the music much. The music was never had an outright political support of one party or another (with some exceptions like the bandwagon for Manley in the early 70s). in the 70s music was ‘political’ meaning it addressed economic inequalities, class and race issues. It became less political because the economy got better and the issues weren’t as pressing and because a new generation didn’t have the same interests as the previous one. It also became less political because drug gangs were replacing political gangs in the power structure."

Did Channel One play the same role that Studio One and Treasure Isle had played to the previous generation? Did the Roots Radics fulfill a similar role to that of the Brentford All Stars/Jackie Mittoo?

"No, because Studio One was originating rhythms were as Channel One was recycling them. The Roots Radics were further recycling the rhythms that Channel One had recycled from Studio One. Jackie MIttoo was important as an arranger. The Radics were a band with Flabba often being the arranger or Dwight PInkeney."

There seems to be an inherent contradictory nature at work with dancehall stars. They are part of a very strict culture that values uniformity yet those who were most individual seem to have benefitted the most such as Yellowman due to his albinism or Lone Ranger due to his status as a foreigner. To what extent do you agree?

"Yellowman actually made it because of his talent. There were several other “dundoos” artists who never made it. Same with Lone Ranger. He changed the style a bit because of his foreign influences but, other than that, he fit right in. Yellowman got a lot of attention for being different – in appearance- in every other way, his values and his behaviors were quintessentially Jamaican."

Can you explain what specials are and what purpose they served in dancehall?

"Specials started out as dubplates in which the name of the sound system playing the dubplate was called. It was a boast, or a challenge to another sound in a clash, or competition. Originally, these were just test pressings which the producers would give the sounds in order to gauge the potential of a new track before it was released to the public."

Just how important was the ‘Sleng Teng’ riddim? Wayne Smith’s cut wasn’t actually the first digital dancehall track though was it?

"No, but it was the first hit. It had the prestige and power of Jammy’s sound system behind it and his contacts at home and overseas. He got good distribution and publicity. He is a very good businessman. People had been experimenting with drum machines since the 70s, most prominently, The Wailers’ bassist, Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett and their producer, Lee Perry."

When people talk about dancehall now in reference to artists like Elephant Man and Sean Paul, sonically, what are the major differences from the dancehall of the 70s/80s?

"The beat is different The newer artist are heavily influenced by rap, hip hop and MTV. They have a more aggressive style but also a more uptown style – meaning the production values are often more sophisticated and complex with the use of professional digital programs. A lot of the ‘roots’ artists these days have a slick sound that would have been considered too ‘soft’, too ‘lover’s rock’ for the ragamuffin crowd in the 80s. (In my opinion.)"

If you were packing a box to DJ, which ten 7"s would you make sure were in there?

Wayne Smith – ‘Under Me Sleng Teng’

Lone Ranger – ‘M 16’

Tristan Palma – ‘Entertainment’

Barrington Levy – ‘Under Mi Sensi’

Barrington Levy – ‘Here I Come’

Mighty Diamonds – ‘Pass the Kutchie’

Tenorsaw – ‘Ring The Alarm’

Cocoa Tea – ‘Sonia’

Supercat – ‘Boops’

Denis Brown – ‘Revolution’