The term dancehall probably reflects Jamaica’s insatiable thirst for invention and novelty in musical terms more than it reflects the inventiveness of its musically inclined islanders. In the broadest terms it was a catch-all term for Jamaican pop music from the late 70s onwards just as it had been known as reggae before then. (And rocksteady and ska previous to that.) This is not to say that it didn’t reflect subtler changes in the musical and social landscape. The walking bass line and emphasis on the offbeat may have provided a direct link to the immediate past but it also reflected the soundsystem-attending punters’ demands for The New Thing. It’s entirely possible that the popularity of Bob Marley, Horace Andy and Steel Pulse et al in the UK and America may have provided the impetus for clubbing Jamaicans to search for a new sound they could regard as entirely their own. It’s true that by the time albums like Exodus were released in 1977, many reggae fans worldwide were getting tired of the syrupy classic rock production (more appropriate on Eric Clapton or Procul Harum albums) watering down the impact of the genre. Also, quite simply, the collie slow riddims and sufferation of roots music didn’t make for an excitable Saturday night out on the tiles.

So the BPMs were increased for the ease of dancing – to this day the genre seems to attract more dance moves than any other; from the well known (bogling) to the obscure (signaling the plane) to the daft (the sponge bob). The sheer density of sound which had been suited for the contemplative effects of ganja was thinned out to be replaced by clipped rhythms and prominent, tight bass. Also just as Michael Manley’s socialist administration had given way to the right wing JLP government, conscious lyrics gave way to the escapist. This included a certain amount of braggadocio, ‘slackness’ (sexual explicitness) and violence. The latter was often a metaphor as in Conroy Smith’s excellent 1988 cut ‘Dangerous’ (included here) where he lists all the different ways he poses a risk to the listener, just to qualify himself: "Dangerous, I am musically dangerous." Of course this didn’t stop boxer Nigel Benn from adopting it as his theme music. And if subtleties were missed in that case, there were plenty of dancehall tunes that weren’t open to much misinterpretation such as Buju Banton’s despicably homophobic ‘Boom Bye Bye’. On the surface women didn’t seem to fare much better than gays and lesbians, often being objectified as little more than sexual objects. Yet female artists were noticeable by their presence, with bona fide stars such as Sister Nancy, Lady Ann and Lady Saw giving as good as they got. Here, the excellent Sister Nancy’s ‘Only Woman DJ With A Degree’ is as exactly as ace as it sounds. While it would be wrong to ignore the negative impact some artists have had on the dancehall scene, it would also be incorrect to characterise hatefulness as a major characteristic. More to the point Soul Jazz do the right thing here by concentrating on the cream of the many excellent riddims and styles the genre threw up rather than giving space to the objectionable. There’s nothing that can spoil the enjoyment of an otherwise great Greensleeves comp like hearing an unexpected and undesired exhortation to fire a bazooka at a lesbian, or something as equally stupid.

The real sonic leap forward came with the invention of digital dancehall in the early 80s, which saw the replacement of some of the live band element with cheap keyboards and drum machines. The use of factory produced Casio equipment (as much to save money on session musicians as to push the sound forward) necessitated a sonic change. The basic set up only allowed for a simpler, harsher riddim, probably first exemplified by ‘Sensi Addict’ by Prince Horace Ferguson, but it really only came to prominence with Wayne Smith’s still fresh sounding ‘(Under Me) Sleng Teng’; a jolly tale of hiding one’s ganja under one’s voluminous rasta hat when representatives of the local constabulary make an unexpected house call. The harsh rock ‘n’ roll aping digital backline proved such a hit, it was versioned no less than 200 times, with one of them featured here, Tenor Saw’s ‘Pumpkin Belly’.

In the standards category we have ‘Murder She Wrote’ by Chaka Demus and Pliers, a 1992 cut by the production powerhouse/backline of Sly and Robbie around the latter’s ‘water drum’ riddim. Also the suitably infectious ‘Diseases’ by Michigan and Smiley which is based around a version of Alton Ellis’s ‘Mad Man’. And arguably the definitive version of ‘Here I Come’ by Barrington Levy whose tongue-tripping refrain of "Shoodlee boop dee woodlee diddlee oh-woah-oh! Zee-wee-oh! Oo-ee-oh! Shoodlee waddlee boop deee woodlee diddlee woah-oh-oh. SWEEN!" was still to be heard echoing round the urban dance halls of the UK and Jamaica some ten years later during the golden years of the ragga/jungle crossover.

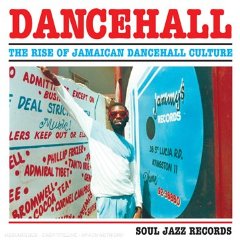

Soul Jazz, as always with their awesome scene based compilations, are not trying to make a ‘definitive’ document; rather attempting (and succeeding) to present an intoxicating and effervescent anthology that will delight the absolute novice and general fan alike with a mix of standards, rare-as-rocking-horse-shit gems and interesting versions. In this respect it lives up to the high standards set by albums like 300% Dynamite, New Orleans Funk: The Original Sound Of Funk, Rumble In The Jungle, In The Beginning There Was Rhythm and many, many others. Another essential release by the UK’s premiere reissue label.