I want to talk about the relationship between author and reader and what we mean by "reader"; the political potential of modern fiction; and the end of "silence" in modern art. These issues are all addressed – implicitly or explicitly – in Ben Lerner‘s recent novel, 10:04. His answers – even his willingness to ask new questions – mean that the novel is more than just a success. It is a quiet revolution, all the more effective for its humility.

The history of twentieth-century art is the history of diverse opposition. Form vs content; style vs substance; experimentation vs tradition; detail vs minimalism; outward vs inward; realism vs the avant-garde; sincerity vs irony. Anterior to these oppositions, from a literary perspective, are various assumption about how the writer should address the reader: giving or withholding, hospitable or hostile, fawning or contemptuous.

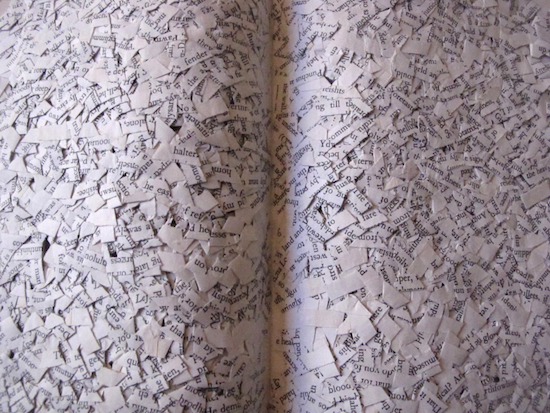

For much of the century, modernity sided with the writer. Progress demanded difficulty: a shift away from representation to abstraction; a tendency to focus on the methodologies and assumptions of fiction-writing rather than the traditional concerns of plot, character and social comment. Walt Whitman’s claim that form was a curtain which could be easily drawn, revealing unadulterated content behind, was decried as naive. Instead it was form all the way through, entangling content, informing it.

This bias towards the artist might be explained by the changing status of art consumers. Prior to the mechanisation of art in the late nineteenth century, the audience for most artforms was circumscribed. Paintings were commissioned by wealthy patrons; music was written for upper class attendees of the symphony halls; literature was limited to the literate and educated.

The twentieth century has seen a rapid expansion of art’s potential consumer base and, therefore, a growing suspicion among artists that the audience might include the wrong types (Stewart Lee has expressed his worry about the type of people who, uncontrollably, might watch and laugh at his comedy at 3am; even Jonathan Franzen, the scion of reader-friendly writing, balked at the idea of an Oprah recommendation). The twentieth century problematised audiences in new ways. There had always been space for contempt (for the philistine commissioner, the tone-deaf duke). Now that space had expanded exponentially. With it came experimentation and, sometimes, outright disavowal of those artistic features appreciated by most audiences

This had implications for the relationship between writer and reader. As literature – and art in general – progressed through modernism and post-modernism, it moved further away from what most readers – or viewers – assumed about what art should do.

James Wood has criticised the archetypal Amazon reader who criticises a great novel for lacking believable or sympathetic characters. But this is uncharitable. For centuries, these were considered valid – perhaps crucial – means of analysing a work. Insofar as art arose as a religious activity – tales of the prophets, images of the gods – then sympathy was considered paramount (although their objects flickered between fact and fiction, the slim peninsula where mythology resides). Artworks were designed to inspire love for heroes, contempt for the cruel. Even difficulty – obscure mystical passages, say – was intended to improve the addressee, inspiring a sense of the profound mystery of existence.

While art has moved on – grown increasingly aware of its own limitations and the limitations of connection/sympathy in general, grown more satirical, more cynical – its audience has stuck to the old assumptions. This dissonance has not really been addressed. Those writers who have deemed it a problem have often located their works in an older tradition, spurning modern developments altogether. See, for example, Franzen and Eugenides, each of whom has drawn on the 19th-century social novel (interestingly, each began in the tradition of the modernists).

Sontag, analysing the ambivalence of artist towards audience, diagnoses an "aesthetics of silence". She speaks of modern art’s “chronic habit of displeasing, provoking or frustrating its audience”. This might involve an artist abandoning his work altogether. More commonly, it involved the artist creating works of increasing obscurity, hostility and density. All were partaking in Beckett’s dream of "an art unresentful of its insuperable indigence and too proud for the farce of giving and receiving”.

The archetypal drifter to silence is James Joyce (cf Dubliners compared to Finnegans Wake, whose noisy nonsense is just another form of silence, more poignant for being unintended – last words: "will no-one understand?"), but the same phenomenon can be found elsewhere. Compare reviews of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and NW (itself an anachronistic rendering of the old modernist tropes) and you see the same grievances: the newly wilful difficulty, the neglect of "sympathetic characters" and a "good story". Even the most benevolent writer, it seems, end up ambivalent towards her audience.

Some have sought to redress these grievances. Franzen is probably the best known. He has put great stock in his Midwestern upbringing as a kind of inbuilt barricade against pretension (read: difficulty). In ‘Mr Difficult: Wiliam Gaddis and the Problem of Hard-to-Read Books’, Franzen advocates

a compact between the writer and the reader, with the writer providing words out of which the reader creates a pleasurable experience. Writing thus entails a balancing of self-expression and communication within a group, whether the group consists of "Finnegans Wake" enthusiasts or fans of Barbara Cartland. Every writer is first a member of a community of readers, and the deepest purpose of reading and writing fiction is to sustain a sense of connectedness, to resist existential loneliness; and so a novel deserves a reader’s attention only as long as the author sustains the reader’s trust…

So the writer is no longer at war with potential readers. He is a member of a shared community, with obligations and duties.

Significantly, though Franzen speaks of community, his concept of the writer-reader relationship is bivalent. It is the relationship between a writer and each individual reader. His benevolence is satisfied regardless of whether one or one million people read him. As a reader, Franzen seeks “a personal relationship with art”. He exhorts us to “think of the novel as lover: let’s stay home tonight and have a great time”. His is therefore an audience of one, multiplied by however many people buy the book. He is addressing us all individually, second person singulars, in the simplest terms. It’s the same for the few novels written in the second person: the implication is that the reader takes the address as a call to them personally. Calvino asks me to interpolate myself into If on a Winter’s Night, a Traveller. He is not asking us all to do it together.

In 10.04, Lerner has explicitly addressed the issue of address. In the process he has overturned the old dialectic, steering between the Scylla of solipsistic experimentalism and the Charybdis of "reader-as-lover" naïve realism. He has spurned silence for the sake of its opposite, without abandoning experimentalism. In doing so, he has reconfigured the nature of the addressee in art (though tentatively, his approaches hedged around, aware of the possibility of failure). All of which is to say, this novel is a finely sculpted success, setting itself unusually ambitious goals and achieving them with a quiet elegance.

Lerner is doing something different to Franzen, and much more revolutionary: he is addressing the second person plural. He is addressing us all.

Collectivity – the subsuming of the one in the many – pulses through 10:04. It is intimately linked to the repeated notion of proprioception. Wikipedia defines the term as "the sense of the relative position of neighbouring parts of the body and strength of effort being employed in movement". It is what the octopus lacks and the human possesses. At least, with regards to his own body. As the novel progresses, the narrator comes to recognise his own lack of proprioception in relation to society. The difficulty of locating oneself as part of a larger body. Sitting on a miniature stool, discussing his aortic condition with a young doctor, he imagines himself as an octopus, his body parts stranded, unconnected.

During and after Hurricane Irene, the first of two bookending meteorological near-misses, the narrator extends this intuition to city and society. Through a series of set pieces he comes to reflect on the context of the actions and events of the novel. He imagines a discussion with his unborn daughter, who quizzes him on the global socio-economic relations that obtained at her birth. On discovering that his proposed novel would receive an advance in the "strong six figures", his mind wanders to the exchange value of the advance, in terms of Mexican labour etc. Buying supplies from Whole Foods in preparation for Hurricane Irene, he reflects on the global reach of economic products – the deep, horrible social relations that culminate in him holding a jar of instant coffee. He delivers a speech on the intertextual history of Reagan’s Challenger speech. Against this growing realisation of his own place among a larger mass – the place of economic goods and artistic creations – the theme of the novel-within-the-novel shifts from one of past fabrication and irony (a decent summation of Lerner’s first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station) to one of sincerity and optimism.

This drift towards society does not result in a call for revolution or sweeping change. Instead it develops through a kind of gathering metaphor partaking in the full range of artistic media (Lerner has spoken before of his view of the novel as ekphrastic: an imaginative space permitting the curation of critical theory, literary criticism, pictoral art, poetry). It is a crucial tenet of the book that the more meaningful – perhaps the more effective – change is hardly change at all. It involves almost imperceptible shifts from one state to another: usually shifts in perception that – as with the examples above – result in an awareness of connectivity to a wider whole.

The epigraph of the novel, taken from Walter Benjamin, is a Hasidic parable of how the world to come will be just like this one, only a little different. Totaled art; scarcity of goods during a crisis; Donald Judd sculptures seen against a desert backdrop rather than the white wall of a Manhattan gallery: all involve slight perceptual modifications. The novel is all about delicate shifts. Alien context, Lerner implies, entails greater proprioceptivity. And the inevitable question arises: what other kinds of perceptual shifts might there be and what socio-economic implications might they have?

Alongside all the metaphors of connectivity and networks (a preoccupation of recent American fiction, from Pynchon through Delillo to Foster Wallace), there are multiple examples of reaching towards. Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc reaches her hand towards the viewer as she hears the summons of the angels; the narrator waves at an old lover; Klee’s angel of history stretches his hands to the past; the Challenger explodes in its attempt to reach to us and pull us into the future; Marty McFly reaches his hand to his face as he vanishes in Back to the Future; the narrator cares for a young intern in Marfa, touching him, kissing his forehead, as he wallows in a ketamine hole, holds the hand of a Guatemalan child he takes to the Natural History Museum; and sleepily caresses his friend’s body (the friend who will one day give birth to his child).

Where Leaving the Atocha Station limned the many forms of insincerity and dissimulation, 10:04 is full of gestures of touch and sympathy. As the metaphors of proprioception gather together, and the motifs of hands waving and caressing and reaching multiply, the reader is left with a sense of the disparate becoming one. But humbly, one touch at a time, one perceptual shift at a time.

This is the background to Lerner’s thoughts on address and his overturning of "silence". To Sontag, modern "silence" echoes those Greek tragedies – described by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy – that were performed without audience. Arthur Danto in his essay ‘Artworks and Real Things’ imagines a playwright named Testamorbida who declares his latest play to have been everything that happened in the life of a family in Astoria on a Saturday night. Neither the family nor anyone else knows that the performance has taken place. This audience-less piece is motivated by Testamorbida’s disgust with theatre. Wittgenstein – the most avant-garde and modernist of philosophers – abandoned philosophy and fled into silence, contemptuous of the very possibility of philosophy. He told his audience – in this case his students – to take up something useful instead.

Borges, as he often does, encapsulates this drift in a short story, ‘The Secret Miracle’. A Czech Jewish author, Jaromir Hladik, condemned to death, begs God for another year to complete his masterwork. God grants his wish but not by staying the hands of his killers. Instead time pauses as his executioners fire. A year passes in Hladik’s mind, during which he perfects the play. As soon as the final line is finished, time resumes and the bullets tear through him. The story perfectly encapsulates the artist-without-audience. A work of art may attain its highest value, it suggests, in the total absence of an audience. In a sense, Hladik has only one audience: the men aiming their rifles at his body. The audience as murderer: hostile and cruel. In Hladik’s work, nothing is given, nothing received. Beckett would have approved.

Ben Lerner, like Borges and Beckett, is an experimental novelist. He operates within the strictures of modernist/post-modernist form. There is a narrator who may or may not be the novelist. There is a novel-within-a-novel. There is non-linearity and allusions to "real world" criticism and theory. There is the inclusion of niche research (the physiology of sea creatures, aortic conditions) that James Wood suggests is indicative of a certain strain of contemporary fiction. His previous novel satirised ironic distance and insincerity while profiting from that irony. Ben Lerner has not retreated from those aspects of the novel that are, on a Sontagian reading, off-putting to general audiences.

Yet the great influence – in ideology if not style – is Walt Whitman. The poet of the future American people. An experimental poet who argued for a democracy of art.

The novel takes an ambiguous stance on Whitman. He is seen as perhaps too arrogant, too sure of himself. The narrator expresses discomfort at the noble pleasure he took visiting the wounded boys of the Civil War. Where Whitman was sure, Lerner is hesitant.

But Whitman spoke in a pre-modernist voice. Not only did he make no attempt to restrict his audience. He expanded it beyond the actual to the potential. Leaves of Grass addresses the American people, present and future. He addresses them, moreover, with sympathy. Asking them to join him in his mystical lounging, to walk with him. He makes himself large enough, vague enough, that he can contain the world. He is the antithesis of Beckett.

And he not only addresses individual readers. He addresses the American people as a whole. It is easy to imagine Whitman recited to an undifferentiated mass of his countrymen (as he often is, at valedictory addresses and presidential speeches every year).

Lerner, uniquely, synthesises this appeal to the second person plural, a political appeal, with the knowing methods of modern fiction. Those methods are put to the use of that appeal. The spiralling metaphor and motif, the meta-artistic references, the mixing of truth into fiction (walking through post-Hurricane Manhattan, the shared gaze at the Challenger crash): these combine to make his appeal convincing, sympathetic. The post-modern conceit of the narrator rethinking his novel over the course of the novel (the final product being, of course, the novel you hold in your hands) is made to do moral work: it suggests, by analogy with all those other instances of perceptual shifts, a desirable movement towards sincerity and sympathy.

The same point might be made in terms of that other enthusiasm of modern fiction (and of Lerner): the young urban flaneur wandering through the city and thinking. This has been a feature of various recent works, from WG Sebald to Teju Cole. Traditionally the flaneur is a passive spectator. Baudelaire conceived of it as an aesthetic mode, best summed up by Isherwood’s line at the beginning of Goodbye To Berlin: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking".

In 10:04, the narrator’s wandering has a different tone: he walks with a friend, Alex, with whom he cries; he looks out on Manhattan and, no longer passive, imagines himself as part of some larger entity. The flaneur of 10:04 is absorbed, for a moment, into something great: something political, and therefore active. His passive gaze at lower Manhattan is the silence before activity: a glimpse of future possibility. It is the flaneur de-aestheticised, suggesting a framework – possibly inadequate, maybe too modest – for future change. And the second person plural address leads the reader out of herself, to recognise a shared body of readers that might, itself, be a framework for a future body corporate.

This kind of political plea differs from, say, the advocacy of liberalism in Freedom. There, the political points made – for example in the discussion of the Iraq War – were "internal" to the novel. We might agree or disagree; it might spur us to protest or alter our political opinions. But that is not the point. The conversation is tightly linked to the characters: to their biases, flaws, motivations. In that sense, it is "political" only in the sense that Walter Berglund is a "man". It is a fiction that happens to mirror reality. To use Kendall Walton’s phrase, it is art as make-believe. The straightforward realism of Freedom blunts the force of its message. It is pure fiction designed to please the reader. Read as a direct political exhortation or comment, its politics jar with the rest of the work. After all, Franzen sees the novel as a romantic night in with a lover. The bedroom is no place for political activism.

10:04 avoids this inconsistency between fictional pleasure and political force. In part because Lerner is not limited by a commitment to a realist plot. He points repeatedly to the shadowy space the novel occupies, somewhere between fact and fiction. The short story around which the second part centres is a New Yorker piece written by the narrator. In fact the short story was published in The New Yorker, and was of course written by Lerner. This makes the border between the fictional and real worlds more intimate, allowing for exchanges of information and sympathy that are precluded in Freedom. It is made clear throughout that the narrator recognises the work as a work of fiction, to be read by readers. He is therefore able to manipulate the text for a political purpose – examples of collectivity and reaching – and address it to us as such. Mostly, though, it is his use of the second-person plural. His address reminds us that there are others. His writing reminds us of ways in which these others might be reached; how we might all grow more aware of the wholes of which we are parts.

It is the narrator’s (and by implication, Lerner’s) aim to "become one of the artists who momentarily made bad forms of collectivity figures of its possibility, a proprioceptive flicker in advance of the communal body". By putting the tools of the most modern fiction to this esteemed use – spurning both the suspicion of the modern artist towards his audience and the temptation of others to move only individual readers – Lerner has potentially achieved that goal. He projects himself towards a theoretical body corporate by evoking poetic instances of transformative communality in his work. He provides examples of transformation throughout 10:04, culminating in the final example of the work itself.

In both form and content, 10:04 is the most (quietly) revolutionary modern novel I have read. Lerner has filled Sontag’s silence with a whisper and replaced contemptuous distance with forms of human sympathy. It is only a proprioceptive flicker, but one that could form a communal body. The rest might not be a collective political roar, but it is far from silence.

10:04 is out now, published by Granta