Open City is three years old. In many ways it feels older. Steadily gaining ground as a modern classic, Teju Cole’s debut novel has proven itself to be far more than your stock tale of immigration – the poignant, if slightly exhausted, account of idiosyncrasies emerging from a clash in cultures. It is a novel applicable to anyone living in a modern metropolis, navigating the streets at the same time as their own psychology. A story about social anxiety, mothers, birds (of the avian, as opposed to colloquial, variety), parties, friends, buildings, feelings and yes, to some extent, the loss of confidence when living apart from your family and the place where you grew up. It’s an exercise in dislocation. A slow and steady walk through the world’s most famous metropolis – once the bastion of civilisation, now a worn and weather-beaten relic, still full of life but deeply flawed.

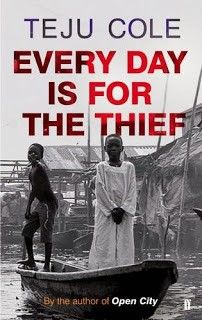

Cole himself is a photographer, sometime novelist and the author of a much loved Twitter account. He took a break from the latter after crowd sourcing first-person pictures of people watching the World Cup Final and mounting them here. He’s a regular contributor to The New Yorker, writer in residence at the Bard College and when he’s not doing all that he’s usually travelling the world giving talks. It was during one such visit, ostensibly to promote his second novel Every Day is for the Thief, (which reads as a reflection to Open City in its account of a young man living in New York and returning for a short trip to his native Nigeria), that we met last week.

In between juggling all of these different projects, what are you writing at the moment?

Teju Cole: I’m writing a non-fiction book about Lagos that includes interviews with people. I wanted to write a book that set out to give you an idea of what everyday life in the city is like. Because Everyday is for the Thief is fictional and also written from the perspective of somebody who doesn’t live there. And also include memoir of me living there. I left when I was seventeen.

Nigerian culture is suddenly very hip. Do you think that’s a good thing?

TC: I always come to this with the view that Nigeria is the size of France with 122 million people and I believe that by rights, a country that large should have a voice on the world stage. The population of America is perhaps twice that of Nigeria, and we certainly hear a lot from them. Why? They’re no more important as people. There are fewer French people than Nigerians. Fewer British people and we hear a lot from them too. In that sense I have a very straight forward approach to rights and equality, which is: every Nigerian person should be as important as any other person.

But can that be equality really be achieved through cultural appropriation?

TC: Well I don’t exactly love that stuff, but it’s almost like we have to pass through that phase. Like India has always been appropriated but over the past few decades a lot of Indian voices have also asserted themselves on the international scene. The doors might have been opened through appropriation, but now a lot of Indian people do what they want without reference to American or British interests.

Do you think you were able to assert your voice because you had experience of living both in Nigeria and America?

TC: I certainly think it helps that neither of those cultures are strange to me now.

Do you see Every Day is for the Thief as a sister text to Open City?

TC: I think they’re very related in quite peculiar ways. The narratives are similar with enough in common for you to know that they came from the same writer. And they’re both maddeningly connected to me in some way, which makes it very easy for people to assume that my narrator is all me. Or at least very close to the person I am. People are often surprised to find that I am quite extroverted.

Is that because your narrators are usually quite elusive?

TC: That’s right. They’re quite introverted. They give a general vibe of, ‘Oh I’m interested in many things but I can’t be bothered.’ Now I’m interested in many things but I do get engaged and it surprises me that people think I’m this serious, introverted person. I wrote a piece only yesterday which, might I say, is pretty fucking hilarious.

You’re more active on social media than a lot of novelists. Do you get people following you on Twitter who have never read the books and vice versa?

TC: Yes, there can be a lot of separation between audiences. Sometimes people tweet at me saying, “You have a way with words, you should write a book.” I also encounter people who see this serious, intellectual side in my books and then they come to Twitter and are thinking, ‘who’s this frivolous jerk?’

I think a lot of people like their literary figures to be unreachable, especially in the US, which by being on Twitter I’m not. Commenting on current affairs is not something novelists really do in the US. A novelist isn’t going to write an op-ed about Isis or drone warfare for the New York Times. Which is strange, because anywhere else in the world, a novelist is someone who also has a column in a national newspaper.

Bret Easton Ellis and Irvine Welsh both push the envelope more than me on social media. Except that Irvine Welsh has a lot of British followers that are more accommodating to ‘bad behaviour’, whereas Americans are more puritanical. They’re very keen for people to be inoffensive.

I think British culture is going that way too…

TC: There’s very good reason for political correctness and not using language to denigrate people but then there’s a line that gets crossed where we govern people’s free speech. Let adults be assholes if they want to be, it’s not illegal.

Did you anticipate the huge response that Open City attracted?

TC: No, [laughs] absolutely not. It was experimental from the beginning. I sent it over to a dear friend who doesn’t bullshit me – ‘Oh it’s very good, all the words are spelled correctly’ you know – and she wrote back saying, “you really wrote the book you wanted to write, you didn’t hold back and you didn’t make any concessions.” Which was encouraging but scary. I was like, ‘shit’ she’s told me I’ve written this thing that is way out there. I knew the chances of even getting an agent, getting published and being reviewed were near to impossible, but being as widely reviewed as it was? Not a chance. It was a series of unlikely hoops. I know my work has quality but a sequence of good fortune led to a weird book like this getting reviewed everywhere. Somehow out of the pile of books to be reviewed at the New Yorker, James Wood pulled mine out of the pile and gave it four pages. A few weeks after it had been reviewed, that covered four pages no less, it got reviewed everywhere.

It felt like it came at exactly the right time. The narrative of development – here’s New York, the most civilised place on Earth that the rest of you, especially African countries should aspire to, culturally and economically – was shown in many ways throughout the 00s to be something of an illusion. Certainly following the economic crash. In that way the book seems to fit with the mood of the late 00’s and early 10’s.

TC: There was a sense of mourning. A lot of people had very complicated feelings about the wars America got involved in too. There was a sense of grief and one of the most gratifying things about Open City was how much New Yorkers embraced it. I think it helped them slow down in their own city.

Birds play a big part in the book and elsewhere in your journalism. Why is that?

TC: I like them because they represent other life. About a year ago I did an event with Vijay Iyer, one of America’s leading jazz musicians and Himanshu Suri, the rapper from Das Racist. Iyer and I did a suite called Open City, ten parts that he and I built around all the bird passages in the book and I did readings in between. It opens with geese then sparrows looking for a place to eat, starlings forming a vast cloud. There’s one moment with a hawk and then the final passage with the wrens, smashing into the Statue of Liberty.

I’m interested in birds as a different form of life which has as little understanding of what it’s about as we do, and the fact that they’re aerial, so have a different point of view.

Every Day is for the Thief and Open City are both available now, published by Faber & Faber in the UK