Doctor Who is a televisual institution and cultural phenomenon which has so far spanned seven decades. John Higgs, one of the UK’s most unfailingly original authors, has written a book on the series which concerns “change, mystery and the importance of imaginary characters in our lives” while mirroring a lifetime of “social, technological and cultural change while always remaining a central fixture of the British imagination”. This short extract concerns the head-scrambling philosophical questions raised by Ben Wheatley’s snow globe…

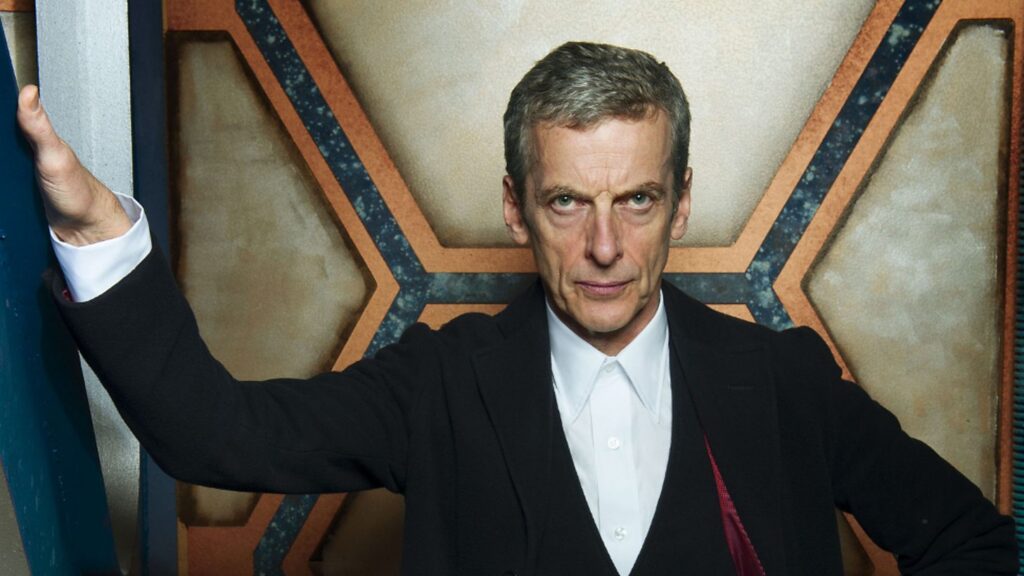

The debut episodes of Peter Capaldi’s Twelfth Doctor were directed by the prolific Ben Wheatley, a filmmaker whose credits now range from the black-and-white English Civil War psychedelia of A Field In England to the half-a-billion-dollars grossing Jason Statham aquatic actioner Meg 2: The Trench. At the start of production, Wheatley approached the art department with an unusual request. He wanted them to build an exact replica of the snow globe from the final episode of St. Elsewhere, an American medical drama from the 1980s. There was no reference to it in the script, but the art department dutifully built it anyway.

The snow globe featured in the last scene of St. Elsewhere’s final episode. This showed a teenage boy named Tommy Westphall sitting on the floor, staring intently into the globe and rocking slightly as his father entered. This was Dr Donald Westphall, one of the main characters in the series, a senior doctor at the run-down Boston hospital St Eligius. But somehow the doctor was now a construction worker, returning home to his family after a long day at work. Donald’s father, who had previously died in the series, was sat dozing in a chair, babysitting. What we were seeing was clearly a different reality to that of the rest of the show.

Tommy did not respond when his father approached or talked to him. ‘I don’t understand this autism thing, Pop,’ a despairing Donald said to his father. ‘Here’s my son, I talk to him, I don’t even know if he can hear me. He sits there all day long in his own world, staring at that toy. What’s he thinking about?’ The series ended as the camera tracked into the snow globe, revealing that it contained a replica of the St Eligius hospital. In the final moments of the series, we discovered that St. Elsewhere had occurred in the mind of an autistic boy vividly imagining the events occurring inside a snow globe. It was a bold, unexpected twist, if one that was not universally popular with the audience.

The twist became even stranger after the rise of the internet, when people started discussing the deeper implications of this scene. St. Elsewhere had included several episodes in which its cast had crossed over into other television series. For example, in a 1985 episode called ‘Cheers’, Dr Donald Westphall and some of his colleagues visited the Boston bar that featured in the sitcom Cheers. Here they met characters including Norm, Cliff and Carla. Did this mean that in the fiction of St. Elsewhere, the sitcom Cheers was also part of Timmy Westphall’s imagination? And if that was the case, then surely the Cheers spin-off series Frasier was as well?

In what became known as the Tommy Westphall Universe Hypothesis, people began to investigate just how many television shows existed within the shared universe of Tommy Westphall’s imagination. Thousands of connections were discovered, and programmes as diverse as Breaking Bad, The Office (both British and American versions) and the 1960s Batman were all shown to be connected. Before long it seemed that pretty much any scripted television show was part of Tommy’s imagination, if you hunted for connections with enough ingenuity and wit. That one simple snow globe, in other words, contained almost the entirety of television drama.

To give an example of how this works, we can include Doctor Who as part of Tommy Westphall’s imagination in the following way. As we’ve just seen, both Cheers and Frasier are part of the same fictional universe. The character of John Hemingway from the John Larroquette Show once called into Frasier’s radio show, so that show is also part of the shared universe. The Yoyodyne corporation, which would manufacture spaceships in Star Trek: The Next Generation, was referenced in The John Larroquette Show. In the Buffy the Vampire Slayer spin-off series Angel, the interdimensional law firm Wolfram and Hart did work for both Yoyodyne and Weyland-Yutani, the evil corporation from the Alien franchise. A Weyland-Yutani spacecraft was seen in an episode of the sci-fi sitcom Red Dwarf. In a different episode, alert viewers would have spotted the TARDIS in the background of the Red Dwarf hanger bay. Doctor Who, by the logic of interconnected and referential film and television programmes, therefore exists inside the formidable imagination of a child staring at a snow globe.

Or at least it did, until Ben Wheatley took that snow globe and intentionally placed it inside the Doctor’s TARDIS. ‘I now wish I’d put it somewhere more where you can see it,’ he said. ‘It just went in with all the tat in the TARDIS re-dress they did for Peter Capaldi. I don’t think it’s on camera anywhere. I didn’t make an effort to get it in shot because I thought my work had been done at that point.’

Doctor Who had always claimed other stories. As Terrance Dicks often joked, what you needed for a Doctor Who adventure was a good, original idea, it just didn’t need to be your own good, original idea. The programme would often lift stories from films, television shows and books, force the character of the Doctor into them, and see what happened. Stories as diverse as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise or Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda were all retold as Doctor Who adventures – renamed The Brain of Morbius, Paradise Towers and The Androids of Tara, respectively. What Wheatley had done, however, took this idea much further. He had performed an occult act. He had added something hidden and unseen by the audience, but which was still considered to have meaning and impact – in the mind of the director, at least. ‘I thought I’d take the oldest television programme, more or less, and put all of television inside it. It made sense to me. The power of this show that had been around forever – it should claw back all of American television. It was a conceptual power grab.’

We often think of television as a trivial thing, but this does it a disservice. In Light of Thy Countenance, a comic written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Felipe Massafera, television is given a voice. It understands how much human awareness is focused on it and its power to attract our attention. ‘You sit at night there on the couch beside your partner yet have only eyes for me,’ it tells us. ‘You listen to my voice in rapt attention yet grow bored or easily distracted when your loved one speaks.’ Billions of people spend hours every day focused on television, and the stories it tells. People had worshipped at altars and idols for untold millennia, yet those objects of reverence have not received anything like the amount of attention that television absorbed in the late twentieth century. No god in history has received as much devotion.

Wheatley’s ‘conceptual power grab’ established the idea that Doctor Who contains all of television – while still paradoxically remaining part of television. In a similar way, the series Doctor Who also exists within the fiction of Doctor Who. That, at least, appeared to be the implication of a scene in 1988’s Remembrance of the Daleks, which was set in London in 1963. Ace left the room after she had switched on the black-and-white television, so she did not hear the continuity announcer telling us that ‘This is BBC Television. The time is a quarter past five and Saturday viewing continues with an adventure in the new science fiction series, Doc—’ The programme then cut to the next scene, but it did appear that Ace had narrowly missed watching the first episode of Doctor Who. That Doctor Who exists within Doctor Who was confirmed in 2014’s In the Forest of the Night, in which a bus can be seen with an advert for the series on its side.

The TARDIS was inside the snow globe, yet the snow globe was also inside the TARDIS. That uncanny blue box exists inside television, yet it contains the entirety of television storytelling. This is not rational thinking. It is mysticism. The within is without. As above, so below. The logic of this situation may not satisfy the materially minded – but rationality is not what powers Doctor Who.

Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story Of Doctor Who is published on 10 April