Alistair Fruish, the Northampton author, has completed a new novel which is constructed of one single sentence… that just happens to be 46,000 words long.

Fruish, whose first novel, Kiss My ASBO came out in 2013, also restricted himself to using words of one syllable when writing The SENTENCE, which will be out later in the year.

He has been busy as he is also one of the editors of Alan Moore’s epic Jerusalem novel, which will be coming out this Autumn.

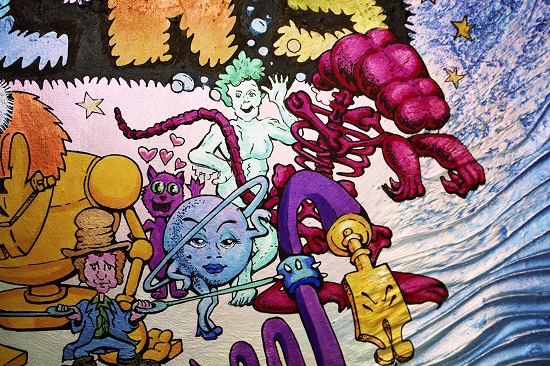

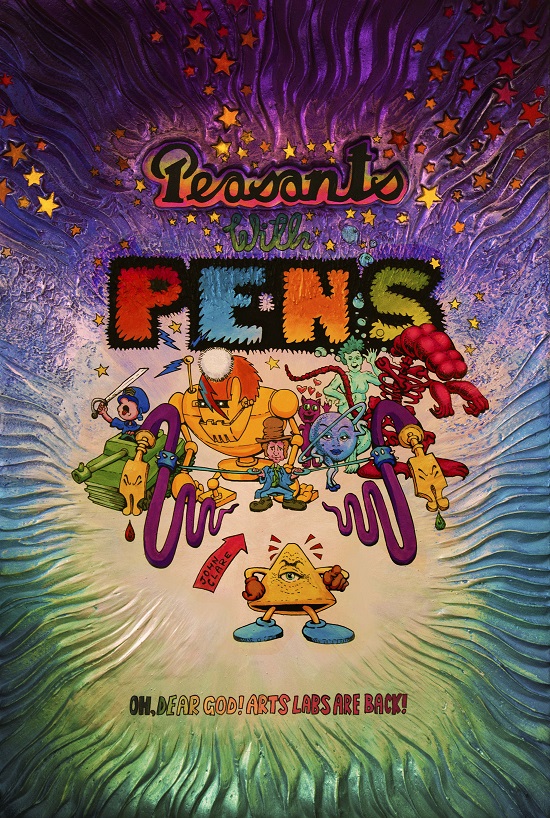

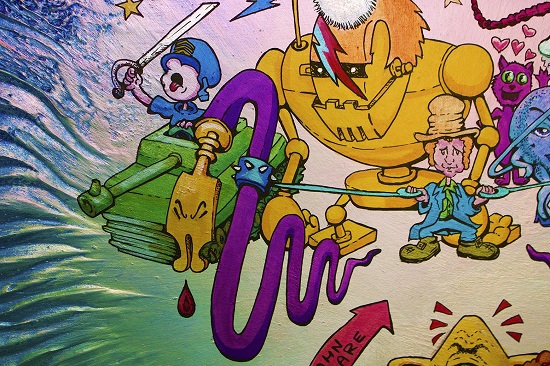

When we spoke to Fruish recently he told us that a piece of artwork created by Moore and Victoria Stothard has been put on eBay in order to raise money for the publication of a magazine called Peasants With Pens.

This new publication has been created by the newly revived Northampton Arts Lab. For the cover, Moore created the original characters, typography, and layout and then Stothard turned the piece into a striking painting.

We spoke to Alistair recently about Northampton’s new underground magazine and the difficulties of writing a one sentence book.

Hi Ali, normally when I interview people via email, I have a set of criteria that I like to pass on in advance. The first of these is, please answer in full sentences and don’t restrict yourself to just one or two sentence answers… Although I’m slightly worried about what might happen if I give these instructions to you.

Alistair Fruish: Yes I can see why you might be. Even though my second novel, THE SENTENCE is just one 46,000 word long sentence, it’s now nice to be able to be able to use full stops again. So I am enjoying the luxury.

Tell me a bit more about the novel.

AF: The lack of punctuation wasn’t the only creative restriction in the book, each word is a monosyllable too. It makes for a very hypnotic effect, that is fiercely rooted in the contemporary argot of the underworld and the street. I’m pretty sure that no one has written anything that sounds remotely like it. I am trying to put the novel back into novel. You could also see it as a kind of punk or grime Under Milk Wood.

This is not pastiche Oulipo or a gimmick; there were a number of good reasons for approaching the composition that way and this technique actually does enhance the work.

What is it about?

AF: It concerns a drug that slows down time, that is given to a prisoner as a punishment in a near future situation, after a series of “black swan” events have changed England quite a lot.

The book is a poly-genre text, being simultaneously a hyper-modern horror, an extremely black comedy, urban social realism, a crime story, a satire, a prose poem and “sink estate science fiction” (which is what Alan Moore called my first book, Kiss My ASBO). So it’s a sentence in both senses of the word. It’s strongly influenced by the last 15 years that I’ve spent working as a writer-in-residence in the English prison system. I have tried to turn the derisory use of the word monosyllabic, to describe a certain perceived lack of eloquence in the so-called underclass, completely on its head.

It was also kind of re-wiring exercise. Although I have quite a good ear for rhythm – and this always influences my writing process – I am dyslexic, and found it hard to get my head around syllables. After writing The SENTENCE this is no longer a problem. The dyslexia was also a motivation for working with prisoners. Literacy levels are very low amongst the prison population. And I am interested in ways of increasing them. I have been very gratified by how positively my first novel, Kiss My ASBO, has been received by prisoners.

Can you tell me how you dealt with some of the inevitable problems that writing a one sentence, monosyllabic novel must have thrown up? To me it suggests a very linear progression through the story for example but I could be wrong.

AF: Most of it was approached in a linear manner. But not all of it. I wrote various sections separately and weaved them in. The section in which I explain Robert Anton Wilson and Tim Leary’s Eight-Circuit Model Of Consciousness in words of one syllable, was written quite early on, but comes later in the book. It is actually quite important to the narrative. I wanted to get that bit written because I was invited to read at the Find The Others Festival in Liverpool in 2014, which was part of a production of the Cosmic Trigger play, put together by Daisy Campbell.

The first conversation I ever had with a prisoner was about Robert Anton Wilson – who was one of his favourite authors, and the Cosmic Trigger figured heavily in this conversation. Now I find I get name checked in two of the new introductions to the recent reprints of RAW’s work – including the Cosmic Trigger – which is quite a strange development.

But yes, there were lots of problems, by limiting my vocabulary so much. Certain things are very difficult to talk about. Numbers particularity are quite restricted. However, the whole process was a machine for avoiding cliches. And despite the often bleak subject matter, it was fun to write.

I’m getting a headache just thinking about it but without punctuation isn’t it a hard read? Is it the sort of book you should read in one or two sittings maybe?

AF: If you read it in more than one sitting you might want to mark the page – as it is just one long block of text in a stream of consciousness style, but nevertheless there is definitely a story. If you look away and get lost. Just start again somewhere. This possible experience, you might have when reading it, fits with the fucked with time-frame the story is concerned with. It’s a super slo-mo situation. The direct events of the novel take place over just one second, the rest is recollections.

Is the book not in the standard, episodic style that most novels are arranged in with Sections, chapters, paragraphs etc or is it more of a stream of consciousness style thing?

AF: It’s just one long sentence with absolutely no punctuation, apart from the inherent – or ghost punctuation – that comes through consideration of the word order. Though because each word is monosyllabic that seems to make it easier on the brain in a way. The general consensus about it seems to be that you have to learn how to read it. And that takes about the first two pages, and then it becomes quite easy to read. Because it is bolted together around "sense units" that are largely built around conjunctions. So they seem to function like separate sentences as far as your brain is concerned. Once you get used to it.

Where do you know Alan Moore from?

AF: I invited Alan Moore into my school when I was a teenager in the mid 80s, to interview him for a magazine we were making back then called Tripping Yarns, not realising that they had flung him out of the school for dealing acid, the generation before – and in that first conversation he told me about a comic story he was writing with a very limited vocabulary. And we discussed the importance of creative restrictions. And it’s something that stuck with me. And I guess – it informs the work that I do in prisons. Which is one of the most restrictive environments you can imagine – yet we manage to get a lot done in there.

I hear you ended up helping edit his epic novel Jerusalem – how terrifying was that job?

AF: Yes. Well I wasn’t proofing it thank god. I’m dyslexic, so that really would have been a nightmare. It’s longer than the Old Testament. The actual editing was very satisfying. It was a great pleasure, to help him polish it. People are going to love that book. There isn’t anything like it. I had given Alan various pieces of information that he’d turned into whole chapters. So to see what he had done with those facts, that was really quite special. It was also a job tinged with sadness, as the reason that he had me, John Higgs and Donner Scott look at Jerusalem – was that the original editor of the book, Alan’s best friend Steve Moore, had died. And he was a really nice bloke. Who I liked a lot.

I had looked through various other people’s books in advance of publication, Jerusalem was the fifth book I have done that for, and I know quite a bit about Northampton. So I guess Alan thought my eyes on the book would be of value – I seemed to be surprisingly fearless when it came to telling him what I thought. Fifteen years as a writer-in-residence working with prisoners helped there I guess!

Can you give me a tit bit about Jerusalem?

AF: Well, no sorry, I am sworn to secrecy – so I can’t talk about Jerusalem, but what I can do is give you an exclusive about something else. There is forthcoming auction on eBay, of a collaborative work of art by Alan Moore and Victoria Stothard. Which is part of the cover design for the first 21st Century Arts Lab magazine, Peasants With Pens. This contains work by members of the new Northampton Arts Lab, which includes me and Alan. This new iteration of the Arts Lab idea spontaneously grew out of the countercultural conference Under The Austerity The Beach, which took place in Northampton last year. And we are planning lots of things. This auction is designed to raise money to pay for the printing of the first magazine. Which is looking pretty fantastic. The magazine will be out soon and will feature work by Alan Moore, Victoria Stothard, Megan Lucas, a dusted off Martin Marprelate, myself and many more local artists.

Can you tell me a bit more about the history of art labs and why you thought it was time to reboot them?

AF: The Arts Labs were an alternative arts movement, that sprang up in 1967, when an arts centre was started up by Jim Haynes on Drury Lane in London. Subsequently others were started all round the country. They were an influence on artists such as David Bowie and the Stuckist Charles Thomson, Billy Idol and Brian James of the Damned, as well as influencing a young Alan Moore. We are attempting a 21 Century re-boot, because after the Counter Cultural Conference in Northampton last year a group of people came together with the intention of making more things happen here in Northampton. We needed a name and Alan suggested we call it the Arts Lab.