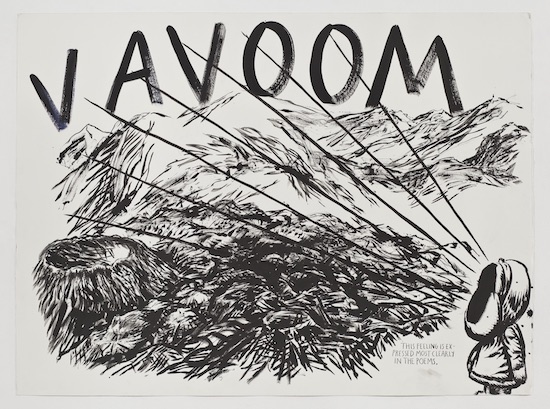

No title (This feeling is), 2011. Pen and ink on paper, 37 1/4 x 49 1/2 in (94.6 x 125.7 cm). Aishti Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon. Photography courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

“Are your motives pure?” The quote sits atop an illustration of a young surfer, shook by the fifty-foot wave at his back as he dives, guns-blazing into the weight of it. Captured from a distance, the piece has a certain gravity to it, a seismic calm in inky monochrome forever teeming toward collapse. With implications of multi-directional motion, the text offers a reflective moment amid frenzy, a quizzical insight into the mode de vie of the coastal counterculture as Raymond Pettibon scrubs at the zen beneath its soapy subcultural surface.

For Raymond Pettibon, counterculture has long been an obsession that transcends the daily round. Most known for his album art and logo design for Black Flag, Sonic Youth, and Minutemen, Pettibon’s work boils the snarky contrarianism of a generation of American punk and hardcore to its essence in ragged ink-and-wash glower. Warping images of hippies, politicians, and other pop-culture prodigies into insolent introspection, the text-heavy illustrations offer a reflexive look at the changing generational tides, waging war on cultural signifiers or sometimes simply laughing at them. Studies of baseball, Batman, and the Beatles are accompanied by large-than-life messages that unravel America’s headstrong machismo with a campy wink of irreverence, one that sprawls across sounds, poetics, and the sociocultural status quo.

A new retrospective at New York’s New Museum, Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work brings together over 700 pieces in an intimate look at the artist’s three-decade career. Spread across three floors, pieces are roughly grouped by theme and most centrally follow the artist’s interests in authority – the claims to legitimacy of politicians, the self-derived mythos of musicians, and the ways in which popular figures are complicit in the production of their own narratives.

Like Joan Didion’s seminal essay collection The White Album, Pettibon has long been drawn to these hypocrisies of American liberalism, where this disconnect between media narratives and folky observationalism manifests itself in a number of wry, yet charming ways. Zine covers riff on popular magazine typography, adding images of drugged-out nudists leaping from vacant buildings, while other illustrations morph LA deadbeats into parodies of their dwindling claims to hippiedom. Pettibon’s punks become brutish caricatures of masculinity or campy, Tom-of-Finland-esque flâneurs, while women worn out on sexual liberation instead embrace theft and violence, perhaps literalising the sort of reactionary media characterisation that would follow in years to come with the Reagan administration.

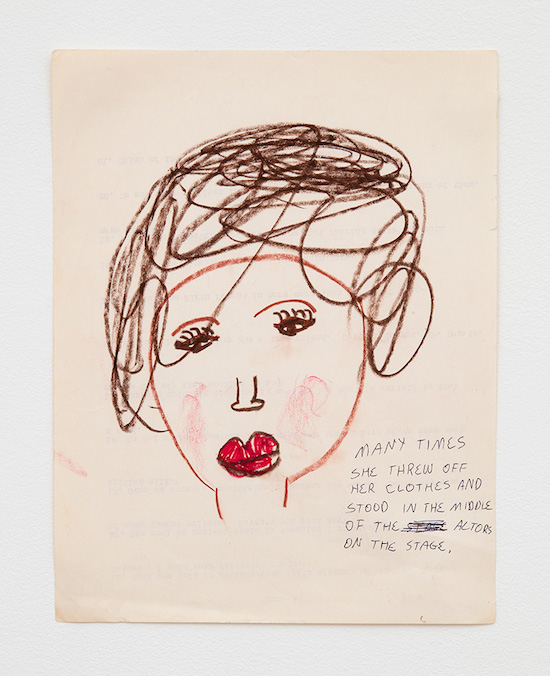

No Title (Many times she…), ca. 1960s/2000s. Crayon and pencil on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 in (27.9 x 21.6 cm). Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

In one video collaboration with Sonic Youth members Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon, Pettibon scripts a banal blockbuster riddled with amusing one-liners that find comedy in an era of decline. “Premature ejaculation is revisionism of the worst sort,” states Gordon at her most pointed. “We have to give a message that it will not be tolerated.” The lines almost anticipate the stoned solipsisms of Austin epic Slacker two years later with a sharp undercurrent that lies deep at the heart of both Pettibon’s text and the long-winded works of Sonic Youth’s finest moments.

On the more iconic album cover for their major label debut Goo, Pettibon wrings comedy and unease from stoic rockers, christened with the caption, “I stole my sister’s boyfriend. It was all whirlwind, heat, and flash. Within a week we killed my parents and hit the road.” In true Pettibon form, the text sheds a certain sobering light on art-rock infidelity, overturning the last remnants of domestic hierarchy and making the almost-Oedipal murder now drab and dull and deadpan. In the exhibition, the work is accompanied by lithograph prints of Minutemen’s Paranoid Time as well as the New Underground compilation Life is Boring So Why Not Steal this Record. Pulling pieces from their own narratives and into a strident collapse of context, the display highlights Pettibon’s unmistakable voice across projects, aestheticising the impossible realism beneath punk and hardcore’s gritty defiance with a cutting, back-handed astuteness.

Aside from its countercultural insights, the exhibition more broadly engages with Pettibon’s politics, specifically in relation to Western imperialism and neoliberal foreign policy. Ghoulish sketches of Hitler and Stalin hang alongside critiques of the Reagan and Bush administrations, which pair Vietnam and Desert Storm soldiers with scathing lines of battlefront brutality. Where his pop illustrations find wisdom in a sort of nihilistic ambivalence, Pettibon’s forays into politics are starkly anti-war, with some of the sharpest and most to ever come from the artist.

In a 2003 portrait of Osama bin Laden, Pettibon erupts into combative imperatives that lash out against US policy in the wake of the September 11th attacks. Amongst green brushstrokes and otherwise tame representation, he writes, “End the war against the Iraq people. Renounce all wars of aggression (and their enabling policies, treaties, and alliances) directed against Islam.” The critiques continue elsewhere in the exhibition with a condemnation of Barack Obama’s support of Israel and more subtle stabs at Donald Trump, which mock him more as media personality than fascist demagogue.

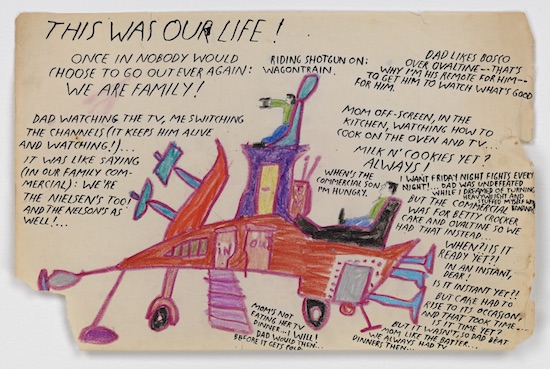

No Title (This was our…), ca. 1960s/2000s. Crayon and pencil on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 in (21.6 x 33 cm). Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

In the midst of such a thorough retrospective, one wonders about the place the once-outsider artist occupies in the contemporary art world. Decades after famed collaborators would find themselves sealed into rock ‘n’ roll history, Pettibon’s art finds strength in its peerless historical presence, even as comparable work from zines of the era slowly fade from popular view. While his almost monomaniacal obsession with such subjects has maybe mistakenly established him as a singular beacon of the era, Pettibon’s work has shown through the rest, playing an unequivocal role in the era’s aesthetics with a voice now deeply woven into the lexicon of a generation. As his work finds its way onto t-shirts and skateboard decks and even Pettibon recognises his own complicity in helping a generation of kids bridge the gap between punk and the art world, the man’s presence almost perfectly crystallises the shift in historicism from small, sweat-drenched scenes to a tentpole of the countercultural mainstream. And for a California surfer with a stiff commitment to contrarianism, that recognition feels more than a little surreal.

Raymond Pettibon, A Pen Of All Work, is at the New Museum, New York, until 9 April