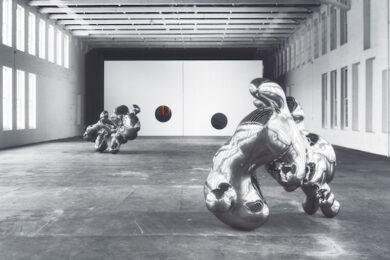

Simon Starling, The Nanjing Particles, 2008. Courtesy the artist, MASS MoCA, North Adams and the Private Collection Jacques Séguin, Switzerland. Photo Arthur Evans

Simon Starling at Nottingham Contemporary

In 2005, Simon Starling turned a shed into a boat, sailed it down the Rhine, and then turned it back into a shed again. The reconstructed outhouse, first exhibited at Basel’s Kunstmuseum before making its way to the Tate as a Turner Prize nominee, finally stood unoccupied, bereft of power tools or gardening implements, with only the traces of its own trajectory – the curved slices through the slats of its walls that had once been necessary to make it shipshape, holes that once held bolts, and so on – for company.

Since winning the Turner for that work, Starling has exhibited widely, with important solo shows in Brussels, Budapest, and Berlin, among others. But this forthcoming exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary promises to be his biggest British show yet, with both new and old works coming together under the aegis of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire’s Grand Tour of the two counties’ artistic treasures.

Starling studied at Nottingham Trent and the duration of the exhibition will see an exchange of sorts, as Joseph Wright’s The Alchemist Discovering Phosphorous of 1795 is temporarily displaced from its usual home at Derby Museum and replaced with a new daguerrotype by Starling himself. Other new commissions find the artist reconstructing the printer’s dots of an old photograph out of actual physical black balls, and weaving music from the punch cards of a Jacquard loom.

Simon Starling will be at Nottingham Contemporary from 19 March to 26 June

Steven Claydon, Towards Chemical Reproduction (detail)

Steven Claydon at Sadie Coles, London

When Craft/Work interviewed Steven Claydon in Geneva last October, he told us he felt "left out of ritual" as an atheist, and talked about developing his own kind of "secular animism" through sculpture. With his new show at Sadie Coles’ Soho Headquarters, the former Add N to (X) keyboardist takes his inspiration from one of the foundational studies of myth and ritual in the annals of anthropology: James George Frazer’s 1890 tome, The Golden Bough.

In The Golden Bough, Frazer defined religion as "a propitiation or conciliation of powers superior to man which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and of human life." It was, he believed, a game of two halves, the practical and the theoretical. Much the same could be said of Claydon’s sculptures and installations through which he seeks new gods for the modern age in the hidden worlds of electron microscopy and nuclear physics. “I’ve realised,” he said back last autumn, “that there’s far more intricate and more interesting magic in reality than there is in the realms of fantasy.”

The Gilded Bough by Steven Claydon will be at Sadie Coles from 1 March to 2 April

The Eye That Articulates Belongs on Land, by Karen Kramer

Karen Kramer & Alice May Williams at Jerwood Fine Arts, London

Five years after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster precipitated by the Tohoku earthquake of March 2011, the area around the crippled plant has experienced a bizarre form of rewilding, with a feral nature clawing back some of the ground blasted by the accident. Karen Kramer’s film The Eye That Articulates Belongs on Land, shown for the first time at this forthcoming exhibition at Jerwood Fine Arts, explores this "blasted wilderness" with a notable lack of romanticism

"We can no longer distinguish the difference between a man-made disaster and a natural disaster," says Kramer. "These are functions of language. They cannot be pulled apart and addressed separately."

Shown alongside Kramer’s film, Alice May Williams’ Dream City – More, Better, Sooner watches the shifting facade of London’s beleaguered Battersea Power Station. Both projects are the recipients of Jerwood and Film & Video Umbrella’s 2016 award. Sam Thorne, Nottingham Contemporary curator and one of the panellists responsible for choosing these projects from the 250 applications, praised "Karen Kramer’s extraordinary use of sound and text" and "Alice May Williams’ playful exploration of online imagery.”

Borrowed Time, featuring new work by Karen Kramer and Alice May Williams, is at Jerwood Space from 9 March to 24 April. It will subsequently be on display at Glasgow CCA from 28 May to 10 July

Renee So, Bellarmine VIII, 2012, ceramic, 50 x 42.50 x 18 cm

Renee So at Kate McGarry, London

Otto, Max, Bellamy, Rafiq, Ezra… Renee So’s art is populated by a curious band of characters, all of whom seem to be in the process of being consumed by their own facial hair. Hand-knitted or kiln-fired, the Hong Kong-born artist’s creations have the appearance of ancient artefacts that have somehow taken inspiration from contemporary cartoons and Edwardian fashions. Everything about them seems out of time and oddly jarring yet effortlessly charming and immediately engaging. But there is magic within these ceramic sculptures and woven tapestries, even if it announces its effects with little fanfare.

Moving to London in 2005, So found, in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Bellarmine or Bartmann stoneware of early modern Germany. Named after Cardinal Bellarmine – known for censoring Galileo – these bearded beer jugs were often used for secreting the esoteric ingredients of magic spells in their 16th century heyday. So’s own pottery practice had begun just shortly before her move to these shores, at a Sunday clay workshop for amateurs.

There’s little info on the gallery’s website about what work will be included in this new exhibition but the artist’s Instagram betrays her current interests in Louise Bourgeois, knitwear, and the Australian artist David Noonan. Quite what will come of such a combination, we shall have to wait and see.

Renee So will be at Kate McGarry from 11 March to 16 April