Gallery photographs by Annik Wetter

In the spring of 2009, bankrupt and recently indicted for federal tax fraud, Wesley Snipes announced a press conference at the New York BookExpo to celebrate a new venture. Zulu Mech 1 was to be a hybrid “cinema graphic novel” about a time-travelling mechanoid Bantu warrior which it was hoped would promote “literacy, hope, and world peace.” At the time, it had been five years since Snipes’s last theatrical release.

Despite Snipes’s stated hope to develop the series into “one of the hottest franchises around”, little has been heard of Zulu Mech 1 since – though Snipes himself, thankfully, has returned to the silver screen with starring roles in The Expendables 3 and something called Gallowwalkers.

But Steven Claydon somehow “happened upon” this ill-fated venture and found himself “really impressed by it.” It led the British artist to reflect on the curious career of this actor, a star since his mid-20s thanks to starring roles in Wildcats and the video to Michael Jackson’s ‘Bad’, and later the founder of his own VIP security firm, the Royal Guard of Amen-Ra. Reverse Magnate, the final work in Claydon’s current show at the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, stands, then, as a tribute to the many “follies” of this once great actor.

The sculpture places a chromed resin bust of Snipes’s über-criminal character from Marco Brambilla’s underrated (1993) film, Demolition Man, upside-down on top of a black plinth surrounded by hanging black magnetic sheets bedecked with a starfield of pennies. “All of his little notorieties started to evacuate until he’s left as this devalued entity, so all these little penny pieces have left him and gone to the wall and he’s left as a sort of vessel, hollowed out,” Claydon tells me when we meet up in one of the town’s many small brasseries, the morning after the opening. “That’s actually one of the most straightforward pieces.”

Born in London in 1969, Claydon studied painting at Chelsea School of Art, but in an act he now describes as “biting my nose off to spite my face” he left to take a job as a guide at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. This experience evidently came as something of a rude awakening. “It’s seen as this very sage institution but it went through some very dubious, dark periods,” he says. “You’re very much aware of the skeletons in the closet – literally.”

The Natural History Museum’s closets are full of all manner of very real, literal skeletons – many of them victims of British colonialism. Claydon remembers frequent protests from Torres Straits Islanders over the fact their ancestors bodies lie stacked up in store rooms, like any old artefacts, amongst dinosaur bones and phrenological exhibits.

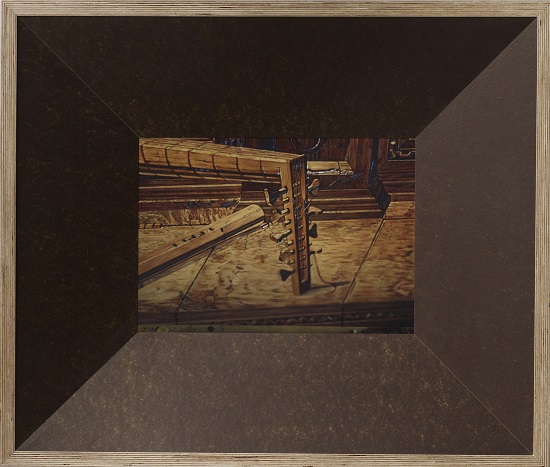

At the same time, his job at the Museum provided an early peak behind the curtain of large-scale display practices. Several of the works in the Centre d’Art show, like the statue of the Roman philosopher Seneca strung up on a brightly-coloured gantry as if still being prepped for exhibition in some warehouse, seem to suggest the memory of this experience. It’s as though his experience in the museum formed a kind of primal scene that his work, with it’s recurrent mix of the hi-tech and museological, keeps circling around obsessively.

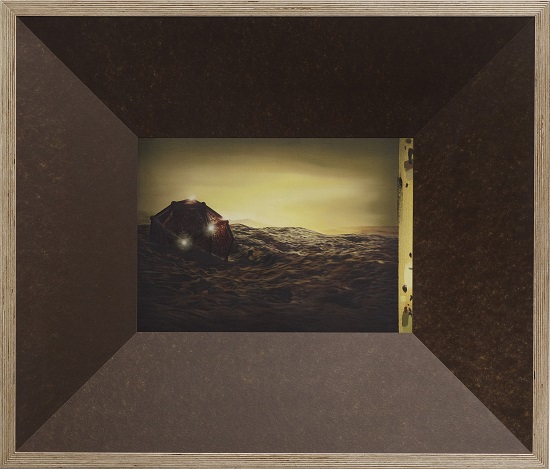

Walking around the exhibition feels sometimes like a peak into some extraterrestrial cargo cult in which a surreal melange of historical artefacts and random detritus from our own planet have been faithfully reproduced and placed in strange new contexts, subject to peculiar and inscrutable forms of scientific investigation. With wires, netting, and copper plates draped around a synthetic log like some cruel parody of telecommunications, there is a totemic quality to many of his sculptures that suggest the ritual practices of lost tribes dedicated to the worship of wave phenomena.

“As an atheist, I feel left out of ritual,” he says. “I’ve realised that there’s far more intricate and more interesting magic in reality than there is in the realms of fantasy.” He tells me he’s interested in developing a kind of “secular animism”, and that he’s trying “to make something that then gets up and walks off. Once that collaboration has taken place, between the material and the idea, then it just kind of charges off. Sometimes I don’t even recognise the things that I’ve made.”

In the art world, this notion of engaging in a collaboration with one’s materials, of letting the stuff speak for itself in some way, might more commonly be associated with Arte Povera, that loose group of Italian artists clumped together by the curator Germano Celant in a 1967 article for Flash Art. But Claydon dismisses all that as “scatter art”. His interest in the secret life of objects springs far more directly from his experience of working with analogue synthesizers as a member of the group Add N to (X) from 1997 to 2004.

“I had always been interested in artefacts since I was a kid. But really it was the kind of animism that you can attribute to a synthesizer, especially an analogue synthesizer. Anne [Shenton] was very much a shaman-like character who really imbued zoomorphic characters onto the synthesizers. They really behave like that: they warm up, they growl, and sometimes they just die. It’s inexplicable. There are gremlins in there. It’s a real collaboration with the machines.”

After his job at the Natural History Museum, Claydon had returned to art school, taking up an MA in fine art at St. Martins. In his final year, he was asked to join Add N To (X) after original member Andrew Aveling quit. “So it was this double life,” he says. “But then Add N To (X) was always quite performative. It had its roots in this sort of post-Minty, Soho environment. So there was a symbiosis. I never really thought of any of the disciplines I’ve been involved in as being particularly discrete, they just have a different complexion.”

Post-Add N To (X), art and music became even less discrete when Claydon was invited to work on some music for Mark Leckey’s film Shades Of Destructors. “We wheeled out a couple of synthesizers and got involved with some friends who weren’t necessarily musicians and started to just create this curious soundtrack,” Claydon recalls. “And it really became its own thing. I think the soundtrack and the film were kind of inseparable from one another. When you see that film, they’re vying for ascendancy over each other: the imagery and the heavy, driving nature of the music. So from then on we kind of thought it would be interesting to make a band out of it.”

They called the band JackTooJack, described by their own LastFM page as “a group of men”, and proceeded to chant, half Marinetti / half Tenpole Tudor, through a film called March Of The Big White Barbarian excoriating London’s dreadful collection of public art.

“It was supposed to be really ham-fisted, a bit 70s gay disco. It had to be a totally inappropriate title for a band,” says Claydon. “We share a lot of interests, me and Mark – things like Kurt Schwitters, Mark had some recordings of Lettrist stuff, some South Sea Islands music… It was sort of a travelogue in a way – but a travelogue of influences. Each piece moves through different environments with bits of field recordings and live recordings that we’d made, and then the analogue synthesizers.”

Analogues, Methods, Monsters, Machines, as the Geneva show is titled, represents what Claydon calls “a summing up and a moving on” with regard to his sculptural practice of the last decade. There are familiar motifs – barrels and doctored statuary, an obsession with frames and frames within frames – but also new springs.

“At art school,” he says, “it was kind of taboo to involve yourself too much in aesthetics or formalism. Any kind of poetry in the work was deemed superfluous. [But] I’m quite comfortable now to introduce formal and aesthetic elements and also to make much more difficult things that don’t necessarily feel like they’re housed within the practice.

“Ultimately,” he continues, “they always do, because the works are based on so many different things, because they’re semi-autobiographical, because I’m 46 years old now and whenever I look at anything I’m bringing all this baggage with it.”

At the same time, as we walked round the show the previous night, he kept mentioning music and electronics. There’s even a work called Pied Synthesizer. “I have been thinking about Add N To (X) again,” he admits. “We have been asked a number of times to reform. Last year we met up again in Gordon’s Wine Bar and we were talking about it but it didn’t happen. We just kind of disintegrated, gently disintegrated and moved off into different areas. It wouldn’t be surprising if we coalesced again.

“When I listen to it, it still sounds like it cogent. Tracks like [1998 Mute Records single] ‘Little Black Rocks In The Sun’ were really phantasmagorical. They were things that had their own life and then moved on as sovereign objects.”