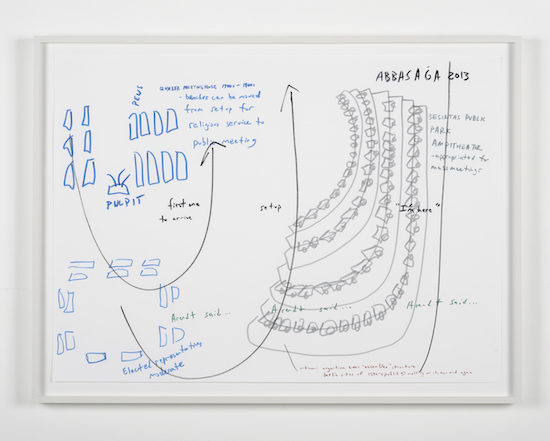

Jeremiah Day, The chair remains empty / But the place is set: Quaker Meeting House – Istanbul Forums, (Performance Notation: October 20, 2015; Gruener Salon, Volksbuhne), 2015, ink on paper, 48 x 66 cm, All images copyright the artist courtesy of Arcade, London

I only noticed the arrow pointing to Bunhill Meeting House after I left. It was a little down the road from the venue I’d been in, round the corner, just a few minutes walk away. There was the van for the Quaker Mobile Library, the sign indicating the name of the estate ‘Quaker House’. We pass these things all the time and scarcely give them any thought. What it means to call a place a ‘meeting house’ instead of a ‘church’, to call the people who gather there ‘friends’.

At the Kunstraum, Jeremiah Day had been riffing on the Quakers and their meeting houses – and the American tradition of town hall meetings, on Hannah Arendt and workers’ councils, on Gezi Park and Taksim Square, and on a small hippie community in Cape Cod and its fight against McDonalds – for maybe twenty, thirty minutes (with a short break in the middle – a “real” five minutes, as he put it). And all the time he was moving. Stretching and flexing his limbs, crossing the room back and forth along the diagonal, lying down on the floor and sprawling out every which way, or standing on a chair and reaching up, then sitting amongst the audience and gesticulating as if gesturing with us, for us.

It feels like a process of mapping – of testing the limits of the space and of his own body, marking each out and plotting one against the other and then, further, against those other spaces alluded to in his speech: Taksim Square, Cape Cod, Berlin streets, New York highways.

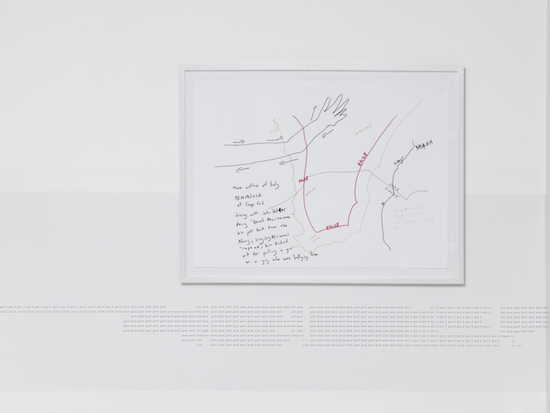

At Arcade Gallery, down another road from Kunstraum, round another corner, a selection of Day’s Performance Notations are framed upon the walls. Looking at them, the day after the performance, I feel some small confirmation of these initial thoughts. Executed on paper a little larger than A2 (at 54 x 72 cm), they look hastily scribbled things, like maps taken down while giving or receiving directions in the street. Within their broad pen strokes in thick blue and red and black ink, we find words plotted out against bodily gestures, an outline of an American peninsular plotted against the Iraq-Kuwait border, the space of the performance venue plotted against that of a Quaker meeting house, memories and anecdotes rubbing up against fragments of rock song lyrics. These frantic diagrams are cognitive maps in which time and space, bodies and place, memories and projections, are one.

The term ‘notations’ suggests something like a set of instructions, evoking a musical score laid out on manuscript paper – and, indeed, I’ve seen graphic scores not so far in appearance from these. But these works are more like records improvised events already taken place, jotted down quickly after the fact, but considered by the artist to be a “better registration” of what he does than any video or audio recording. They capture, not just the sound or appearance of the performance, but some of its energies, some of its psychic resonances. They scramble across the page at the speed of thought.

Day’s Performance Notations take their place at Arcade in a group show called Even Dust Can Burst Into Flames. The title is abstracted from a quote by one of Day’s most frequent absent interlocutors, Hannah Arendt. “In the case of art works,” she writes in her The Human Condition of 1958, “reification is more than mere transformation; it is transfiguration, a veritable metamorphosis in which it is as though the course of nature which wills that all fire burns to ashes is reverted and even dust can burst into flames.” The passage alludes to lines form a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke called ‘Magic’: “From transformation such amazing shapes/ appear. Oh do but feel and trust! / To ashes often turn our flaming hopes / yet art can set on fire our very dust.”

Alongside Day’s score-like works, there are a series of sculptures by Kit Craig – loose squiggles in black, made by a brief tease of wet clay later cast into bronze, here spreading out across the walls like an invasion into reality from the world of Children’s claymation shows like Morph, Trap Door, or Splodges. There is a One Second Drawing by John Latham, a quick burst from a spray can upon a now-slightly-yellowing sheet of A4. And snaking all around the angular confines of the gallery in a continuous wallpapered trail, there is Anna Barham’s We may be ready to have verbal intercourse (score)(2017), the result of a reading group held at Latham’s Flat Time House in Peckham Rye. Each of these works marks in some way the trace of some performance. They are the indexical marks of absent events, rendered tangible. Dust bursting into flames.

One of Britain’s pre-eminent conceptual artists, John Latham’s work was concerned, above all, with the relation between art and time. His One Second Drawings were all executed in the early 70s and drew on his notion of the “least event”. They represented a series of stabs towards finding the most minimal gesture, the slightest thing to remain not-nothing. In an interview with Mute magazine once, Latham described the functioning of this least event in terms of music as “somebody recognising that a sound was interesting and feeling the do-it-again impulse.”

Like Barham’s scores and Day’s Notations, there is something intrinsically musical about Latham’s work. John Cage was enormously important for him. But what comes to my mind when I read that short quoted description in the previous paragraph is not so much Cage as John Oswald – his desire to present the entire history of CD music, compressing some 1,000 samples from popular songs into a twenty minute work, each one intended to be the smallest possible fragment to still retain some possibility of recognisability. In an interview from 1994, Oswald called each of these splintered sounds an “electroquote”, the name implying some sonic equivalent of the subatomic particle known as an electron.

After a performance by Jeremiah Day of his Letter to Turkey at the Volksbühne’s Grüner Salon in June 2016, Turkish artist Burak Delier wrote to Day: “From my perspective, [Gezi Park] was the first time that people felt that they were a society and this was their country and further, that they were multiple, diverse, fragmented, wounded but in spite of all their differences and fears they could live together and make life beautiful … And I think this togetherness with a heterogenous, fragmented, horizontal societal space gives us the potential for expansion and emancipation. This is really crucial. This means that the space is not given, we are actively creating it; we create space while we are interacting with, reacting to, touching and addressing each other. The fearsome void between every group, community and individual had become a space of potentiality. This is how space is created and this is how we can become free.”

Even Dust Can Burst Into Flames is at Arcade Gallery until 3 June