All photographs by Andy Keate

A comma hangs against a shimmering, iridescent background, as if suspended in space. In the West, punctuation was invented by the ancient Greeks as a means of dictating the rhythms of recited poetry. So in a sense, as I pause in front of this work, Breath Mark, a UV print on a metre-long sheet of rainbow holographic paper, I am only following the instructions laid down by the comma itself: to hesitate and take a breath.

As the artist Anna Barham puts it to me, when we meet over coffee a few days later, focusing on a simple, isolated punctuation mark in this way became a means “of signalling where the body is reinserted into the text.” But in Barham’s recent work, the body in question might not necessarily be human.

On a TV screen at the other side of the Arcade gallery in Clerkenwell, suspended upon tentacular steel tubes and clamped to the walls, a short minute-and-a-half long found film plays on a loop. -52nthjt3k8 consists of a single close-up on the flesh of a dead squid. A finger, barging in from the top of the frame, swipes left and right upon its skin, as if signifying its desires on some fleshily aquatic iPhone. At the finger’s touch, countless small spots in yellow and black respond by dilating and contracting, melting together and breaking apart. The colours shift and melt like an image on a monitor.

“For squid,” writes Sabel Gavaldon in an essay printed in a pamphlet accompanying the exhibition, “the skin is a screen – a sensing, pulsing, viscous screen – that remains in a constant conversation with every aspect of its environment. But the question becomes: Are we ready to listen to what the squid has to say?”

For Barham, this journey into the life aquatic began during a residency at Sheffield’s Site Gallery in 2013. “Up until that point,” she tells me, “a lot of work that I’d done was based around written language – working with anagrams and things. Then through performing these anagrammatic texts that I’d written, live – they’re quite tongue-twister-y because of all the repeated syllables and repeated letters – so I became very interested in the mechanics of the mouth, and I got more interested in language as sound.”

Barham programmed her residency at Site as a series of public events, for a few of which she invited the writer and curator Bridget Crone to join her in discussion. Somehow the conversation turned to a text Crone had written for another purpose, about trying to clean a squid. In the text, the squid’s guts fall onto the newspaper she’d laid down beneath it on the table and the letters on the page begin to morph and distort. The thought occurred: perhaps there was some secret affinity between the printing press and the cephalopod. After all, they both work with ink.

Barham became fascinated by this curious text. Reading it over and over again into her phone and watching the curious errors that Siri tended to produce when converting the sound into written sentences. It became a kind of automatic poetry. She collected some fifteen different iterations of this, each one more surreally confused than the last.

Before long, Siri started to get better at recognising its master’s voice. It got too accurate. No fun anymore. So she would use computerised voice synthesizers, getting her Macbook to read out loud to her phone, one computer to another, like a parent to a child. Next she organised reading groups, gathering people together to read these various iterations of the text into speech recognition software, producing new variants in the process.

“That was a really interesting process,” Barham says, “this kind of shared listening and interpreting and performance of the text that was happening in these reading groups. There was no audience. It was only people who were reading. But when it comes out of the software, there’s no punctuation. So there’s this other layer of interpretation that you have to do in order to read it out loud. According to where you break for breath or try to make emphasis, you could make several different texts out of one page.”

Thus sparked an interest in punctuation, and in mounting isolated punctuation marks onto a paper type that shifts its colours in relation to its observer, like the skin of a squid. “Once I had the results, I would spend ages just reading them out loud to myself to understand what they could mean and how they could be interpreted. So there was always this need to take it away from written text again. And basically what you are doing then is punctuating it.”

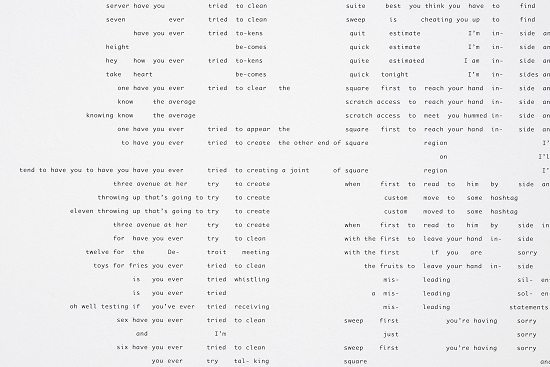

All these different interpretations and misinterpretations of Crone’s original text have been printed up in a double-spaced monotype font on vast sheets of paper, one-and-a-half metres tall and eight metres long, snaking their way around the jutting angles of Arcade’s gallery walls. It reads like the delirium of some manic computer out of twentieth century science fiction. One or other Cold War computer loses the plot after reading Mallarmé and spews out endless skew-whiff skyscrapers of text arranged in irregular blocks.

“Have you ever tried to clean a squid first you reach your hand in-side and try to grip and pull its guts” it begins. 16 lines down it has become, “Have you tried clean scan first reread you can’t inside and tried to call logotypes”. On and on it goes, finally ending up, “You ever tried talking squared inside try to grip like it’s going”.

“Interestingly,” says Barham, “the phone never understood the word ‘squid’ right from the get-go.” Mobile phone voice recognition software works using Markov chains, assigning statistical probabilities to the different possibilities based on the context. So, due to the computer’s own peculiar resistance to naming its double, the squid, “it really struggles to work out what the context is and the whole thing sort of deteriorates.”

Disintegrating the text even further, Barham has begun to collect more readings of chunks of these texts on a special Soundcloud page, this time following the text down instead of across, pursuing each iteration of a single word or phoneme. In a further twist, a video from earlier this year The Squid That Hid reverses the process. Instead of using code to pervert language, this film uses language to pervert code by converting a jpeg into a text file and inserting natural language into the body of the text – replacing, for instance, every “s” with the word “squid” – and then converting it back, now distorted and deformed in unpredictable ways.

“I felt that language is a found object,” she says. “Language is this system that we have to try to express ourselves, all our messy feelings, through.” Referring to Maggie Nelson’s notion of language as a kind of net, Barham says, “There’s huge holes in it, but you can still manage to say something."