Installation View. Charles Atlas at Sheffield Institute of Arts Gallery. Courtesy Art Sheffield. Photo Jules Lister

“When you go back to a place that played an important part in your memory,” curator Martin Clark says, introducing this year’s Art Sheffield, “there is an experience of holding something in your memory, and re-projecting that on the city. There’s a euphoria to that,” he says, “but also a feeling of disjuncture.”

Clark, now director of Bergen Kunsthall in Norway, went to university in Sheffield. But in the two decades since he left, the former home of British steel and the National Union of Mineworkers has changed almost unrecognisably. Coming back here, then, to shepherd the city’s now teenaged biennial, felt like a curious return. “I began to think about the way cities change,” he says. This reflection, it would seem, led to a wider thought about change itself, whether material, intangible, or in some unplaceable hinterland between the two.

As we trudged up the path from the train station, a line from Pulp’s ‘Sheffield: Sex City’ kept springing to mind. “Everyone on Park Hill came in unison at 4:13 AM and the whole block fell down.” The seething eros of Jarvis and co. seemed curiously apt as we slipped into the concrete shell, at the bottom of the listed brutalist block, that was once the notorious Scottish Queen pub. Park Hill’s once most feared pub is currently home to the S1 Art Space where, for the duration of Art Sheffield, Michel Auder’s videos are playing upon multiple screens. Like Pulp’s epic 1992 b-side, they are as woozily prurient as a wet dream.

Untitled (I Was Looking Back To See If You Were Looking Back At Me To See Me Looking Back At You) is a telephoto-lensed exploration of the lives of others as glimpsed voyeuristically through the windows of a large apartment block (not that unlike the one we were in ourselves). French-born, Brooklyn-resident Auder, a one-time habitué of Andy Warhol’s Factory, spent several months surveilling his neighbours. Most of the people he catches on film seem to be either taking their clothes off, touching themselves, or otherwise mooning listlessly about their homes in a kind of languid haze.

Not quite the febrile romance of Pulp, nor the violent potential of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, the film exudes this uncomfortable urban ennui, the stale smell of unsavoury activities that you, as a viewer, become deeply implicated in by the act of watching.

Installation View. Michel Auder at S1 Artspace. Courtesy Art Sheffield. Photo Jules Lister

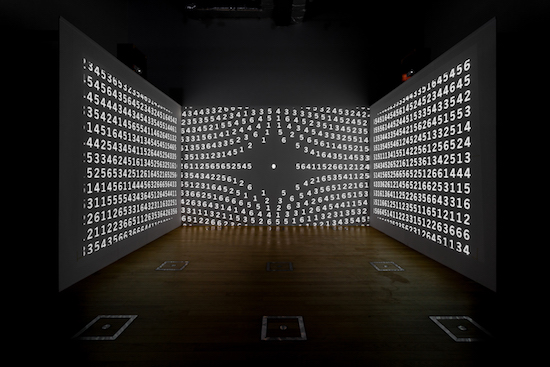

Leaving the estate and heading west, across the implacable border marked by the train tracks and the A61, we seemed also to be crossing another border. From the macro concerns of people-watching in the anthills of modernity, to the micro world of atoms and the void. Charles Atlas’s (2011) film, Painting by Numbers is concerned, as Martin Clark suggests, with “the underlying patterns which produce the material.” Vertiginous and kaleidoscopic, it gives off a heady rush of digital psychedelia.

Atlas is well-known for his ‘dance for the camera’ works of the 1970s and 80s, collaborating with the likes of Merce Cunningham, Leigh Bowery, and Michael Clark. ButPainting by Numbers is quite a different proposition. Taking up three screens in a side room at Sheffield Hallam University’s Institute of Arts, the film presents an unceasing torrent of numerical figures. Numbers within numbers, bursting out towards the viewer in a never-ending flood of data, suggestive of some overwhelming mathematical sublime. For an artist who has historically done more than most to ‘musicalise’ the video medium, this film is notable for its silence – as if hushed by a reverence for obscure algebraic gods.

The university has itself played a significant role in the transformation of Sheffield, in its uneasy transition from industrial heartland to knowledge economy. There seemed to be university buildings everywhere we went, as if it were slowly eating the city alive. Outside the Science Park, Jehovah’s Witnesses nervously proffered their magazines, like well-dressed drug pushers. Ex-industrial buildings – at which our bus driver would glumly point with the repeated mantra, “that’s turning into flats…” – sit uncomfortably next to the newer brick-clad, swoosh-roofed buildings with names like ‘Concept House’.

It is in one of the few remaining remnants of the old Sheffield, an electro-plating workshop called Biggins Brothers, that we find a curious work by Paul Sietsema which itself seems to operate upon some curious borderline between the physical heft of industry and the more abstract virtual spheres of the knowledge economy. In what feels like a rather rickety old place, Sietsema has rigged up a highly elaborate system for looping a long stretch of 16mm film projecting a digital image of a punched steel plate spinning in a void. As the sign spins, the punched dot letters on its surface rearrange themselves from “demi-tasse dinner set” to “white porcelain dolphin” and so on. Each phrase an eBay sellers’ description of real items for sale, each one more suggestive than the last of some surreal suburban hinterland. With each rotation, the real folds into the virtual, the physical into the abstract, in a matryoshka-like serial embedding of worlds within worlds.

Installation View. Anna Barham at BL_NK SPACE at Roco. Courtesy Art Sheffield. Photo Jules Lister

When Craft/Work interviewed Anna Barham last October, she spoke of language as a “found object”, as a system riven with holes. For her new film, 000998146-horizontal-panning-empty-fashi_prores/böhm-on-dialogue-ch5 (2015), presented for the first time for Art Sheffield at the Roco Creative Co-Op, this found object becomes – to borrow a figure from William Burroughs via Laurie Anderson – a kind of virus, corrupting codes and images in violent and unpredictable ways.

We are presented with a single photo of a fashion catwalk. It flickers before our eyes, shifting against itself and glitching erratically. Into the code of the jpeg, Barham has inserted, line by lines, passages from quantum physicist David Bohm’s book On Dialogue.

Bohm was a theoretical physicist who proposed the existence of different layers of reality between the mental and the physical: ‘implicate’ orders in which space and time no longer hold sway. But in his final years he became fascinated by the nature of thought and creativity. His posthumous book On Dialogue proposed modes of free-flowing constructive conversations in which participants agree to suspend judgement in order to build spontaneously on whatever ideas arise without any obligation to produce or conclude anything.

“In such a dialogue,” Bohm writes, “when one person says something, the other person does not, in general, respond with exactly the same meaning as that seen by the first person. Rather, the meanings are only similar and not identical. Thus, when the second person replies, the first person sees a Difference between what he meant to say and what the other person understood. On considering this difference, he may then be able to see something new, which is relevant both to his own views and to those of the other person. And so it can go back and forth, with the continual emergence of a new content that is common to both participants.”

In a way, this sounds like quite a good description of the history of art. But what happens, Barham’s work seems to be asking, when one of the participants in such a dialogue is not human?

Installation View. Florian Hecker at Portland Works. Courtesy Art Sheffield. Photo Jules Lister

Similar themes are taken up by Florian Hecker’s sound work housed in the old Portland Works, birthplace of stainless steel. Using the words of philosopher Reza Negarestani, Hecker puts into effect a dialogue of his own between three hanging loudspeakers issuing, from the far sides of the room, two iterations of the same clipped RP voice speaking about the relationship between nature and culture, from one or the other perspective. In between the two, a third speaker – another virus, perhaps – plays a distorting and interfering role, releasing digital sound objects which eventually come to engulf the whole discussion, confusing and distorting the difference between the opposing interlocutors.

As the piece progresses and the plinking, sizzling, telephone-chewing sounds gradually overcome the voices in dialogue, comprehension becomes impossible. From amidst the febrile melee of noise and distorted noise, I could finally just make out a single phrase fragment: “… a performative approach to nature…”

Martin Clark had spoken earlier about wanting to select works that could inhabit spaces "in a very light way", works that could flicker and dance through the spaces they inhabit, doing their thing "– and then they’re gone. Like a reverie, or a dream." But even though this collection of films and sound pieces has almost no material presence, each work had a density and a solidity that surpasses physical extension. Going round the whole thing in a single day felt impossibly rushed, like a hypodermic injection of ideas too heavy to otherwise ingest. But the sheer speed of thought here is infectious, almost delirious. Euphoria and disjuncture sit side by side. As the city becomes a phantom of itself, these works find a concreteness that is polymorphously perverse.

Art Sheffield occupies venues throughout the city until 8 May