Entering Andrew Grassie’s new exhibition, you’d be forgiven for thinking: is this it? Seven tiny images in a single white room? Five minutes, and I’ve looked round all the paintings at Maureen Paley gallery, read the three-paragraph press release, and moved onto my second round.

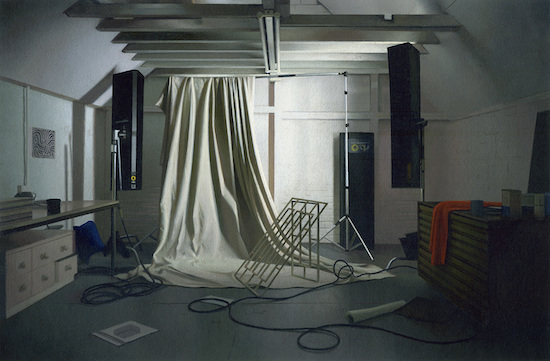

Grassie’s paintings are all the same size, no bigger than a paperback novel. Each depicts a variation of an artist’s studio space. Studio Proposal 1, Studio Proposal 2… You get the idea. The gallery literature tells us that the studio depicted belongs to Grassie, but has been styled, in each image, to create a fictional workspace of another artist.

Perhaps I was naïve to expect a game of Spot the Artist. A few giveaway dots for Damien Hirst. A Hockney swimming pool, rippling into life on an easel. But, alas, there’s no punchline. For better or worse, Grassie portrays work by made-up artists in his fictional studios. So, there’s no chance for art history graduates to feel clever. This isn’t a pub quiz picture round.

Grassie’s seven “studio proposals” look like glorified garages, scattered with vague suggestions of things being made. There are freshly stretched canvases waiting to be primed. Paint pots and coffee cups. The beginnings of sculptures.

From six feet, you’d be forgiven for thinking these paintings are photographs. But from three feet away, the edges soften. Crisp white canvases segue ever so slightly into the walls they lean against. The glass of a cafetière becomes a mini Rothko, black on grey, bleeding. In Grassie’s work, such details are no bigger than your thumbnail, and it’s only when you get really close – kissing distance – that you can see the brushstrokes.

There’s a contrast, of course, between the sublime quality of the painting and the banality of the subject. A contrast that’s heightened by Grassie’s use of egg tempera, a classical method used by Old Masters such as Michelangelo.

Tempera was the primary medium for nearly every painter in the European Medieval and Early Renaissance period, until 1500, when oil paint was invented. By using egg tempera, Grassie elevates the mundane to a higher ground. The studio held on a pedestal, a work of art in itself.

In this sense, his studio proposals reminded me of a room at Fischli & Weiss’s 2006 exhibition at Tate Modern, Flowers & Questions. In the piece Untitled (Tate), the artists presented a 3D trompe-l’oeil of a messy studio. From paintbrushes to pizza boxes, coffee cups to planks of wood, every object in this sculptural simulation was carved in polyurethane, carefully painted to look convincingly banal.

Like Fischli & Weiss’s handcrafted studio, Grassie’s paintings show exceptional skill. A commitment to craft that’s quite moving to see in our screen-saturated world. In Grassie’s photo-realist paintings, we’re asked to be patient, attentive. And as I walked round this small but hugely impressive exhibition, I was transported back to my first art history class, aged 16, and the four words scrawled on the blackboard: Look, look, look again.

It’s a dictum familiar to many who studied art history. A pithy phrase to remember when visiting galleries, writing reviews. But perhaps in our age of transient Instagram images and Snapchat selfies, of fake news and endlessly refreshing feeds, we can all learn something from this dictum. This call to look twice, three times, a dozen times. To really look. To really see.

On the fourth, fifth, sixth rounds of Grassie’s show, I saw something new in each of his paintings. New details emerged. Fresh thoughts in my mind. I thought about how we look at images online, these days; how we consume them quickly, hungrily, then move onto the next.

Nowadays, we live in a state of “continuous partial attention”, to use writer Linda Stone’s phrase, and it affects the way we look at the world. The things we notice. In our increasingly digital lives, art like Grassie’s encourages us to pay attention. To learn, to remember, how to see.

I should be clear that neither Grassie nor the gallery claims his paintings are a reaction to the internet. This is just how I saw them, personally, after a day at my computer. After a bus journey spent sending WhatsApp messages, scrolling through social media… Taking an hour to view Grassie’s work was a reprieve from all that, and for me quite a relaxing experience. Meditative almost, as I walked repeatedly around the gallery, looked again and again at variations of the same image.

At Maureen Paley, the gallery literature doesn’t give much away, but there are hints at the artist’s intentions. At art school, Grassie attempted to escape “the tyranny of content” by copying his own paintings at 1:1 scale. This method evolved, and soon he was painting “droll recordings of the spaces and places of the art world” – gallery offices, storage areas, empty exhibition spaces and studios.

Freed from the “tyranny” of having to decide what to paint, Grassie developed a zen-like approach, a way of working where only the practice of painting remained. In this sense, there’s something deeper, more philosophical, in Grassie’s work, and it’s reflected in the artists he lists as influences. On Kawara, Roman Opalka, Giorgio Morandi. All of these artists are known for making methodical works of art, depicting the same thing over and over.

Cult artist Kawara created nearly 3,000 of his “Date paintings” in his lifetime, painting the date in pristine white letters in his famous Today series. Opalka, a leading conceptual artist, meticulously painted consecutive numbers onto canvas, from one to infinity.

But perhaps the artist Grassie shares most in common with is Morandi, a painter nicknamed "il monaco” (the monk) in his native Bologna, and best-known for painting domestic objects repeatedly. The same bottles, jars, jugs and vases portrayed again and again, in slightly different formations.

Much like Morandi, Grassie encourages us to look at banal objects in detail. To take our time, to really consider them. In an age where many of us spend hours staring at screens, scrolling through pixelated waterfalls of images, Grassie’s work takes the glaze from our eyes. Because how often do we look in detail, these days? How often do we look again?

In times like ours, art like Grassie’s reminds us to really look, not just at art, but at everything around us. The banal, the boring, the often over-looked. By painting his own studio with the rigour of a Renaissance painting, Grassie – to borrow from John Updike – gives the mundane its beautiful due. And in his tiny, meditative paintings, we see how interesting the world is, how beautiful, when we simply pay attention. When we look, look, look again.

Andrew Grassie is at Maureen Paley, London, until 7 January