Neil Kulkarni.

Yesterday I woke up to the awful, awful news that my dear friend and long-time colleague Neil Kulkarni had died suddenly on Monday, aged 51.

Like a lot of people, I’m still trying to process the shock. I’d only seen Neil nine days earlier, when we performed together at Birmingham Town Hall as part of the Chart Music podcast which dissects old episodes of Top Of The Pops. He was on fine form and, in hindsight, I feel blessed that I was able to be around him one last time. The Quietus, one of the prime outlets for Neil’s exemplary, incendiary journalism feels like the appropriate place to pay tribute.

Neil Kulkarni, an iconoclast to the end, would have scoffed at the very idea of a ‘pantheon’. Sorry, mate, but you’re going to have to suck that one up: you’re in it. Let’s not mess about, here. Neil Kulkarni was – Christ, that past tense is a gutpunch – one of the greatest music writers ever to do it. All-Time Top Ten, easily.

Neil Kulkarni’s early life was documented in the series of tQ articles which formed the basis for his wonderful memoir Eastern Spring, published by Zero Books in 2012. His parents, Marathi Brahmins, came from the Indian state of Maharashtra. Neil’s father, a research chemist, moved to the UK in 1963, and married Neil’s mother, a qualified midwife, in an arranged marriage in 1967. Neil was born in Coventry on 26 July 1972, and he and his sister Meera grew up in live-in flats above care homes for the elderly where their mother was working as a matron. (Listeners to Chart Music will be familiar with Mrs Kulkarni and her unerring ability to determine which singers on Top Of The Pops were on drugs, usually because they had dark glasses on.)

By the age of eight, Neil was a junior rude boy and a lover of the 2 tone movement, especially hometown heroes The Specials. As well as the Indian music he heard in the home, he became obsessed with Western pop, and by the time he went to the University Of York to study Philosophy & English (where the first thing he saw was graffiti which read ‘Welcome To The Yuppy Factory’) he was an avid devourer of the music press. Specifically, Melody Maker: a photo of Neil around this time shows him wearing a Young Gods top, which is a blatant tell.

I was working at Melody Maker in the Autumn of 1993 when Neil first came to the paper’s attention. Under the Cheers-based pseudonym Clifford Clavin, Neil sent a series of brilliantly-written letters to our Backlash page calling out the underlying racism of the music press, and its unexamined assumptions about the superiority of white rock music, shining light on its sins of omission. Cathi Unsworth, editing the letters one week, shrewdly picked him out from the bunch and passed one of Neil’s letters on to one of the Maker‘s section editors Jim Irvin (then writing under the name Jim Arundel), who gave Neil his break in the pages of the paper. I was joint reviews editor alongside Sharon O’Connell, and we both quickly realised what a talent we had on our hands, giving Neil as much space and as many juicy jobs as he could handle.

A proud Coventrian, he never left Cov, never moved to London, never had his head turned by the allegiances and favouritisms which inevitably result from a life of schmoozing and ligging with the music industry. The writer Stevie Chick recalls Neil giving him the simple two-word advice ‘Never Lie’, and staying away from London enabled him to stay true to that, to retain his integrity and remain pure. (I’m reminded of The Human League’s principled refusal to leave Sheffield.) Indeed, he became something of a Coventry icon: a photo of Neil shaking hands with a giant milkshake in the city centre (a coded anti-fascist statement, if you know you know) was turned into a painting by one of his idols, Specials bassist Horace Panter.

Away from the biz bullshit, Neil could write without fear or favour. He wasn’t out to make friends. That said, it tells you plenty about the man that he made few enemies (aside from a handful of disgruntled artists, such as a singer who once threatened to break his legs, or the manager of The Enemy after this album review). And it also tells you plenty that he made so many friends anyway.

The first time I met him was the day he walked into Melody Maker‘s office wearing a gorgeous green and cream leather box jacket, one of the most desirable garments I’ve ever seen. (Neil was always a super-stylish dresser, a born dandy.) He exuded effortless star quality and charisma, and I was instantly drawn to him. We became good mates, part of a little sub-generation of Maker writers (even though I was five years his senior).

On visits to the capital he would sometimes crash at my basement flat in Holloway, sleeping on my tiny, rickety, wooden-armed sofa. Often, the times we hung out together would involve the kind of what-goes-on-tour-stays-on-tour escapades which must remain shrouded in omerta. (There are certain codewords which, if he said them out loud or slipped them into a Facebook post, would still have the power to make me crease up with guilty laughter years later.) One of the less scandalous memories is the time, at the end of a particularly reprehensible rampage around Camden Town, he leapt behind the counter of Kentucky Fried Chicken and began giving out food for free because the service was so slow. The author Ben Myers remembers a similar example of Kulkarni taking control at Glastonbury 1997, where he stood at the entrance to the VIP area backstage, refusing admission to bands who didn’t meet his standards. (Supergrass because their second album was disappointing, The Bluetones because he plain didn’t like them.) He was a serious mind, but also one funny fucker.

As a British Asian, Neil was hugely important as a rare non-white voice (along with NME‘s Dele Fadele) on the otherwise overwhelmingly pasty-faced, Anglo-Saxon weekly music press. In terms of musical coverage, he was a necessary corrective, notable for his extensive love and knowledge of hip hop. And he meant Hip Hop, not ‘trip hop’ (which he disdained, arguing “hip hop is a trip”). His incredible review of The Infamous Mobb Deep contained the taunt “All you feelthy toureest scum into the Beasties and Mo’Wax should start considering where they’ve ripped off their entire discography. Hip hop is no style to cop or indulge some Adidas Samba idea of kool. It’s the most constantly changing, vital music being made and Mobb Deep are all the proof you need.” (As a Beasties lover, I felt seen.) This stuff didn’t always play well with the readers. One racist knuckledragger wrote in to complain about Neil Kulkarni always giving space to “your dark mates”. But those attitudes were exactly what we were trying to change, and exactly why Neil was an essential secret weapon for the Maker.

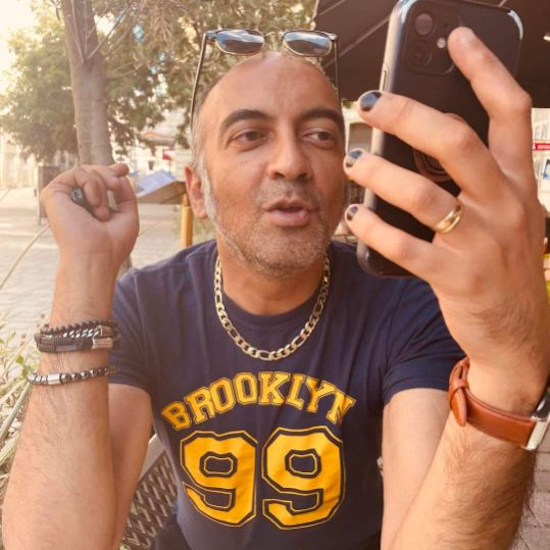

Neil Kulkarni and Simon Price. Photo courtesy of Simon Price.

Not that Neil was just The Hip Hop Guy. He bristled against that stereotyping, and his musical taste was eye-poppingly eclectic. He was just as likely to write about alt rock / art rock artists like Come and Pram. He frequently sang the praises of BBC Radio 3 for its coverage of classical music and the avant-garde. His favourite band was The Rolling Stones. Some of his finest work was writing about conventional rock music. Check out this extract from his live review of Manic Street Preachers at the Astoria in December 1994, Richey Edwards’ last stand:

“OK, see it ain’t attitude cos anyone can do that, just cock a snook and suck your cheeks. It ain’t glamour. Glamour’s boring. Glamour is loud pretty people who hug, hug, hug, giggling at your geek self all night. And it ain’t rock’n’roll; it was your rock’n’roll that made a n**\r hater The King, your Teddy Boys who Paki-bashed for Mosley, Notting Hill 1958, your rock’n’roll that venerates the White Negro, your rock’n’roll built on SAMBO DON’T SELL. I ain’t interested and the Manics are way beyond that.”

Like I said, incendiary.

Neil had a reputation as a destroyer, a hatchet-man. And it’s not without truth: nobody wielded the hatchet quite like Neil. I’ve taught some of his more spectacular takedowns to my astonished students, such as a Ned’s Atomic Dustbin review which consisted mainly of one long sentence, an ad-hominem attack on the sort of people who liked that band. Or a Kula Shaker review which blew apart the industry’s asinine search for the ‘next Oasis’. The bands themselves, though, were merely hapless cannon fodder, caught in the crossfire of whichever broader valid cultural point Neil was making. And, while his prose burned with righteous fury, his rage was always precise, his targets never undeserving. He wasn’t a flamethrower; he was a laser.

It’s important to state, too, that everything he wrote came from love. A love of music, and an understanding that part of the job involved taking a machete to the bad stuff in order to clear a path for the good stuff. Above all, Neil was an enthusiast, an evangelist. And he never lost his excitement about new music. In this sense, Neil put some of us (myself included) to shame. He never fell prey to wallowing exclusively in nostalgia. One of the most telling tweets about his passing came from @t_om_s who wrote “I’ve had his 2023 roundup as an open tab for a few weeks, slowly working through it and finding amazing stuff that’s ignored elsewhere.”

Neil, with fellow Maker survivor Sarah Bee, spoke heartbreakingly about the shameful dying days of the publication on episode 37 of Chart Music. Thankfully, he didn’t give up when the paper folded, but flourished as a freelance contributor to other mags. When I was hired as Features Editor of the apparently well-intentioned, but in reality farcical monthly magazine BANG!, Neil was one of the first calls I made. It bothered Neil that he had an image as a lunatic loose cannon, because he had the discipline to hit a deadline and a word count when required (despite the entertainingly unedited splurges on his Medium and Substack), and he was easily able to find work in the metal press (unlike many intellectual critics, he did not see metal as inherently lowbrow), and in publications such as The Wire, Plan B and Electronic Sound (for whom he wrote a front cover story on Soft Cell only last month).

In later years, his work for tQ was particularly extraordinary. Type his name into the Search box and pick anything he wrote at random, but I can particularly recommend his series A New Nineties (an antidote to Britpop nostalgia, which he loathed), his many love letters to T. Rex (here’s one), and his obituary of Terry Hall.

He also branched out into books (such as the aforementioned Eastern Spring and his vital The Periodic Table Of Hip Hop), bands (most notably the Moonbears) and academia, becoming a brilliant and much-cherished lecturer and teacher. (We were colleagues, for a while, on the Music Journalism course at BIMM, albeit at different branches.)

And, of course, podcasting. When host Al Needham brought a gaggle of former Melody Maker writers together to form the core team of Chart Music, I was thrilled to be working alongside Neil again. We had an easy rapport, and the warmth, humour and love shone through every episode he recorded. He would, for example, rate bands according to whether or not he’d accept a sandwich made by them. (Hard no: The Stranglers. Yes: Janet Jackson, the women in The Brotherhood Of Man, and Motorhead, if only because their thumbprints would leave some residual speed on the bread.) A particular favourite Neil episode is one he recorded with Sarah Bee during lockdown, featuring an absolutely joyous appreciation of Meat Loaf’s ‘Dead Ringer For Love’. And the one in which, to my disbelief, he alerted the world to the legend of the Birmingham Piss Troll.

Neil was a family man. Following the tragic death of his wife Sam in 2018, he became a lone parent (and grandparent), and he leaves daughters Georgia and Sofia, stepchildren Charlotte and Jake and his partner Lenie. Sofia, the youngest, was a regular topic of conversation on Chart Music, and he spoke engagingly about the way she taught him about music (rather than vice versa), forcing him to appreciate various hair metal horrors he may otherwise have dismissed. Parenting his way through grief must have been tough, but also gave him something to live for, an impetus to keep going. Many, in the aftermath of his own death, have been concerned about the welfare of his daughters. A GoFundMe has been set up (to which my fee for writing this article will be donated).

He was also an absolutely brilliant friend. As fellow writer Wyndham Wallace put it, “For a man with ferocious opinions on music, Neil was never anything but gentle in person”. He was always willing to offer wise counsel, and to deliver acts of unsolicited kindness. (Example: last year, when the Wu-Tang Clan top I wanted wasn’t available in my local Primark, he went to the Cov branch, bought it and sent it to me.)

Neil Kulkarni, Al Needham and Simon Price, pictured backstage before a live Chart Music show in Birmingham earlier this month. Photo courtesy of Simon Price

His online persona was also at odds with his militant Mr Nasty image, swooning over his kitten Ophelia, blogging about crisps, and recording Indian cookery tutorial videos (pro tip: put Sprite in your bhaji batter). It was like finding out Huey Newton had a crochet blog.

At the Chart Music live show in Birmingham, we paid tribute to Annie Nightingale for turning us on to so much great music and for never giving up on discovering the next exciting thing. Little did I know that I would be paying tribute to Neil, just days later, for the same reasons.

Anyone who knew him, or even those who only knew him through his writing, podcasting and online presence, will be feeling a little more alone in the world today. He was someone who, in the words of former Kenickie drummer Pete Gofton, “kept the flame” and who “got it”. We can’t afford to keep losing people like that.

In 2009, Neil wrote a Ten Point Guide To Being A Music Critic for Drowned In Sound . The tenth point read as follows:

“Accept that everything you say will be forgotten and ignored but write as if you and your words are immortal. Don’t just describe but justify — make sure the reader knows WHY the record exists whether the reasons are righteous or rascally. And always remember you’re not here to give consumer advice or help with people’s filing. You’re here to set people’s heads on fire.”

Neil Kulkarni’s words are immortal, and will be inspiring us all for decades to come. And, every time a new reader discovers him, another head will be set on fire.

A GoFundMe in aid of Neil Kulkarni’s family can be found here