March 2011: Vultus oriens, Ecce Homo Sacer, Rodus Dactlyus Aurora I don’t have long so listen now, before your house wakes and time starts stealing your future again an ancient song for a new dawn. See the sun? Feel it in your heart. Why is this hi-caste poet teaching this beautiful song to a whore? Why is she singing it more beautifully than he’s saying it?

I’ll keep it short, about survival now, barely controlling those dangerous whims that could become intent. All my life I’ve had this little mental trick, an invisible yet realer-than-real realer-than-me ice-cold ring of steel I can conjure at my temple that makes the heat leave, a fantasy gun-barrel beaded with my own sweat that makes the mind rest, promises deliverance, a platinum doomsday slug to my supersolipsist noggin. Enquiries have been made, access secured and ready to roll. In order for it to stay a trick, and for me to stay alive, a different conversation is going to have to start. I have to find a different party because this one, this black and white one called Western Pop that I haven’t been able to leave until now, is played out, is populated now by the kind of white folk who say "kmt bredren" and the kind of black folk willing to humour them.

I couldn’t give a fuck. Black and white folk have always hated me anyway, as any true second-generation Paki should have learned and never forgotten a long time ago. BUT this conversation is going to have to step off its cultural-tourist treadmill between uptown and downtown, between the right and wrong side of the tracks. I don’t want to sulk and scowl on these stairs anymore. This conversation is going to have to turn around and get possessed by quiet, earth-shaking voices from elsewhere, looking and leaning eastwards and listening a while rather than just hurriedly thieving what’s useful for the old empire, saddling shards of Chinoisery and other exotica to the same old 4/4 modes of transport before militarily rolling them down the streets back home to the ‘oohs; and ‘ahhhs’ of the easily duped and desperate.

Even though I’m of a generation that isn’t in the fearsome situation our parents were in, that rejected the timidity and politeness that was their only available response to all that hostility, I still carry that fear in my cells, still look out for myself and see no reflection anywhere. Ask people about Indian music as processed here and they’ll point you towards Madlib or Timba if smart, more likely M.I.A, fkn Diplo and his Blackberry, 70s/80s garish sleeves of second-hand bud-bud disco pastiche, bhangra, some desi and a lot of UK hip-hop if you’re lucky. More often than not, it’s stuff that could soundtrack an Uncle Ben’s advert, and that’s always if it digs into the past. ‘What can be used, dear boy; what can be salvaged from Indian pop and retooled for Western consumption?’ What stray bits of camp nonsense can get a giggle or sit with a breakbeat; or somehow reaffirm the bouffant-barneted Amitabh Bachan stereotypes we’re comfortable with. There’s always the reassurance of another culture getting Western culture a little bit wrong, a little bit laughable. Like the word Bollywood itself, a construct that needs the West, that can only ever be seen as a charming attempt to replicate Western cultural invincibility, an essentially failed ‘interesting attempt’ that only re-emphasises the West’s inherent, inherited, immortal superiority. Sure everyone’s equal round here. Check the obits.

At the end of January 2011, legend, alcoholic, playback singer, classical vocalist and musical titan Bhimsen Joshi died at the age of 89. He’d been making music for 78 of those years. It is some of the greatest music ever made on this planet. Answer me – had you heard of him? There’s no right or wrong answer there, only an honest one, and if the answer is no it’s not yourself you should be questioning but those who made you, those who are meant to keep you informed, those who decide the fit and constrictions of what you listen to and how you listen to it. Musically, we’re all still looking at the same old pre-47 maps, goggling at the pink bits and wondering what savagery we’re gonna step into. If we’re facing a future in which what is learned is under threat of strangulation in the name of economic purpose and vocation, then don’t be fooled into thinking that a more globalised world doesn’t mean you’ll end up hearing the same old hierarchies. The music from elsewhere will still be processed into what they think is fathomable to you, what can be fed into the grinder to churn out more of the same old same old. You and I have been lied to because what this music, this old, old music, suggests time and time again is not how to refry, reheat, or reinvigorate Western models but a whole new ancient different revolutionary way of thinking about music altogether. This must surely be the next step if we’re going to move on from the dwindling needy dialogue of today’s monochrome eclecticism, the shackles and trade between black and white. See the sun? Feel it in your heart. Flashback.

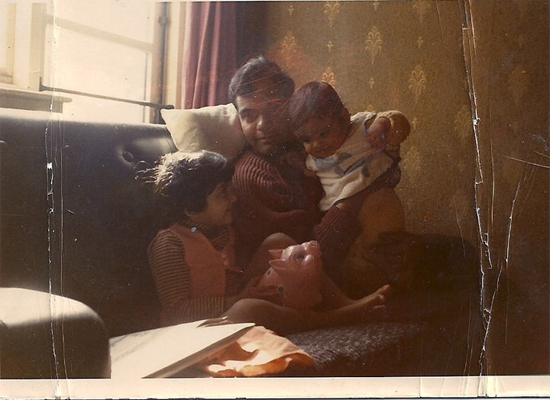

1972-77. Born and back to Wood End, Coventry. Green. Space. Old folks home. No memories at all bar an arm moving across the light from the window, protection. My parents have been in the country five years. My mother, a Chitpavan Brahmin from a reformist family, is the descendent of shipwrecked reanimated corpses from Greece, Iran and the Middle East who’ve been dragged ashore in Konkan 3000 years ago and given life by Parasuram. Her family are magicians and farmers, turn out milk and hexes and she has light skin and a look that means she’s been spoken to like a native everywhere from Italy to Iran. My dad’s family weren’t called Kulkarni until they were given clerical jobs. ‘Scribe’ is the closest translation of Kulkarni, ‘Lord’ is the closest translation of Thakur, his family’s original surname. They all have a blue ring around their black eyes. He came in 1963 with a suitcase that 50 years later is on top of my wardrobe, she came in 1967. In 1972 I am called Neil after Neil Armstrong who was landing on the moon when I should’ve been born, three years previously. My elder sister was born instead, but my parents keep the name and apply it to their son when he finally turns up. This pleases me now, but nothing but milk and Fab bars pleases me for my first two years on planet Cov.

Move to Stoke Aldermoor, Coventry 1976. No space. Another old people’s home. Still no memories bar nights of pain and illness, days of matchbox cars and pillow fights. Starting, perhaps, to realise that indoors and solitude is safety, suits me. One day, my sister thinks she’s killed me but it’s just one of the few, occasionally self-inflicted concussions that I chart my pre-memory childhood with. Trapped in the lift I can’t understand to step back from the door and cry until I fall back. Door opens. Toddle surrounded by people born in the previous century who occasionally die, bequeath their snuff tins to their cellmates. Good spreads, roll out the barrel. Wonderful people with vintage manners not reflected out in the street, where I start to learn that dogs and other kids, don’t really like me. Parents worried that I’m deaf as I flatly refuse to speak. Speech therapist finds out that I can speak but am too shy, a problem I will later bequeath to my own kids. Happy daze – I hear the Seekers and the Sex Pistols and Val Doonican and it all sounds the same. I also hear this song and I realise that music can make me cry and choke. This song is about moonlight, shelter, looking in the mirror and not seeing yourself looking back. It’s by Maharashtrians of a similar vintage to my parents, Hridaynath Mangeshkar and his sister Lata, a familial combination that created gold whenever it collaborated… but at age five I knew none of this. I just knew it felt funny, that this song woke and walked into new chambers of my still-growing heart, instrumentation I couldn’t quite picture that pulled the brine from your eyes in pure melodic yearning and sent you on through your day levitating a few inches above the ground.

A poem that’s over 1000 years old. Hits you like it were writ tomorrow. Move elsewhere in 78. Revolutions Per Minute, learn new things, new prone shapes to throw, new realities. Like real sadness. Like real fear.