A certain form of romance can be found around the edges of languages. People fall in love with untranslatable words – a German word for the feeling of being alone in the woods, a Turkish word for moonlight on the sea, a Swedish word for rising early to hear the birds sing. It doesn’t matter that some of these are archaic, or esoteric terms not commonly used or even known in their respective languages. People want them to exist, just like they want there to be fifty Inuit words for snow. There are however moments in life where you reach the actual limits of language, when words fail in the face of overwhelming experience, so you reach for nebulous terms concerning the sublime or hallucinations or grief. As approximations they are so imperfect they feel not just like failures but betrayals. “The poet’s job is to translate unspeakable things on to the page” Roger Robinson wrote in his Manifesto. It seems an impossible task and yet somehow, just occasionally, through metaphor or melody, they succeed, and the impossible is rendered momentarily tangible. It’s a process that is more mysterious than its practitioners would like. “If I knew where the good songs came from,” Leonard Cohen once said, “I’d go there more often.” The key perhaps is not to see artists as mystics, receivers or even creatives but, as Robinson suggests, translators.

Despite having long admired both, I had never aligned the work of the poet Roger Robinson and the composer Richard Skelton. It may have been the differences in backgrounds – Robinson hails from Hackney, Trinidad, Brixton; Skelton is from Lancashire. One urban, one rural, on the surface at least. Even the places where I first chanced upon these artists emphasised a distance. Bleary-eyed, on the overflowing tumbrel that is the morning Tube commute, I’d read the title poem of Robinson’s A Portable Paradise, nestled between advertisements on the train, and almost missed my stop. I first heard Skelton’s music through headphones trekking through the Trossachs and over Rannoch Moor with a mixtape a friend made me, entitled quite accurately Wilderness Songs, along with a note that ended ‘P.S. don’t die.’

There are many differences in subject matter, style and temperament between the poet and musician, but one crucial uniting factor is that they are both brilliant translators, not of linguistics but things that are even more difficult to translate – the paradoxes of human emotion, the hidden memories of environments, the enigma that is time.

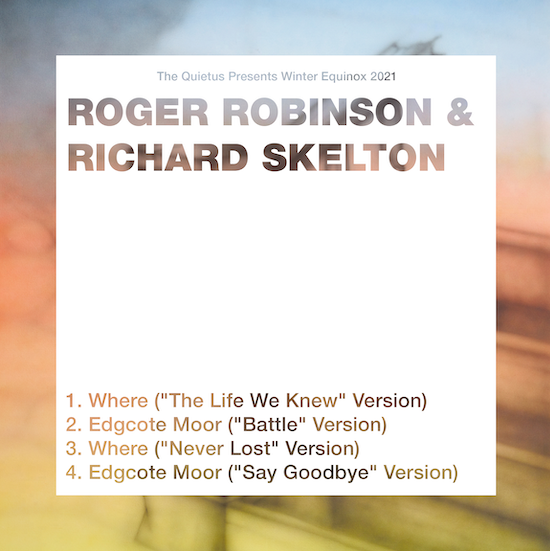

Before talking to them both, I listened to their collaborative, self-titled EP recorded specially for The Quietus. Its arrival, in the depths of winter, with the pandemic peaking again, is timely. There is a feeling of the sea closing in over our heads once more. The Tube seems a Faustian proposition now. The Rannoch Moor might as well be on Mars. What better listening might we have, as the hatches batten down, than songs from other places in space and time?

In contrast to the sense of gathering twilit doom on the EP, the poet Roger Robinson is warm and effusive in conversation. Even when speaking of troubling things, he does so with a sense of momentum and expansiveness that is infectious, “I’ve been thinking a lot about dystopias during the lockdown because, you know, what else?” We chat about a mutual love of Four Quartets and The Pogues, and how poetry is inescapable once you start. As well as building up an impressive body of written work, winning the T.S. Eliot Prize in 2019, Robinson is an enthusiastic collaborator in spoken word and musical projects, under his own name, with King Midas Sound, and a host of others (Young Echo, Fennesz etc.) incorporating elements of dub, folk, ambient and hip hop. We talk about his recent work with The Bug, particularly ‘The Missing’, inspired by Marc Chagall’s painting ‘The Promenade’ (1917) depicting a man clinging on to his lover as she is being swept up into the sky. The song feels like a work of apocalyptic magic realism until you remember that the particular apocalypse represented in the track happened to actual people in recent memory, with the atrocity that was the Grenfell disaster. Such is the power of Robinson’s work, simultaneously soaring and rooting, exploring and advocating, raging and memorialising, all in equal measure.

The source of the opening song, ‘Where’, on the EP is located far beyond the confines of Robinson’s native London, “I’ve been spending a lot of time in Wales with The Black Space Quartet from Snowdonia. Hanging out with them, I got into all this Welsh mythology and history because that’s all they talk about, all the time. I absorbed a lot of it. At the time, there was lockdown and it’s crazy, but nature was kind of provided for me. I’d never been into nature before, but I was going camping, hiking up mountains. I couldn’t travel or do shows, so nature became what I was doing. And I wanted to do something different, and we had all this pastoral Welsh Celtic folklore that was interesting to me. When the music came [from Skelton], I thought, ‘Oh, this would be perfect.’”

‘Where’ is practically a Biblical lament, and echoes down to us via the jeremiads of Horace Andy, Dennis Brown, Gil Scott-Heron, and Cormac McCarthy (who Robinson cites as having channelled), yet it feels like a new departure too, perhaps because these ancient issues of exile and yearning are still with us, maybe eternally so. Robinson has written and spoken a great deal about migration and, both pre- and post-Windrush scandal, what it’s like to invest in a home that does not reciprocate. The song’s refrain “Where, tell me where, on this earth do I belong?” chimes with this theme in his work but this was only part of a story that is more particular, universal, and environmental. “It’s all in there. At the same time, these were inspiration poems. I was out walking with my friends, going up to some waterfalls and they started showing me these abandoned burnt-out cottages. They showed me these bullet holes from exercises during the world wars. It was interesting how much abandonment there was, all the way up to that waterfall; that might have been the only place those who lived in that area could trudge to in order to get clean water. There were different tracks that came to an end in the bush, and you had to turn back and find another path. It’s nature but a nature of abandonment. So, I didn’t even really think of the poems as political. They were inspired by the moment.”

“The text for ‘Edgcote Moor’ came to me when I was camping on a moor, and I woke up in the early morning and went to get some water and, I swear to God, I saw dust on the horizon. It could’ve been a farmer working, kicking up plumes of dust, but it just came to me, if that was horses coming for war, that shit would be wild. I’d have to run back to the village. I wish it had a real deep meaning but that’s exactly how it happened. Who knows why whatever comes to you comes to you? Artists have a thing about knowing intentions but sometimes it’s not all planned. I was on a moor. I saw the dust. I wrote it all in one go: both of them, in fact. Nine or ten pieces came to me that way. One, called, ‘Starling’ is about the Welsh epic The Mabinogion, and the tale of a queen who is made into a scullery maid and has to send a starling to get her brother to come to her rescue. That’s the kind of folklore the Black Space Quartet collect. There was a piece about belonging to the trees, about not belonging to the city but to the trees. So, there was a whole range of poems and songs that were all part of this.”

Robinson’s affinity for the poetics of place and people belies any limiting views we might have of urban and rural cultures. He is a poet acutely attuned to echoes, in (often forgotten) history and landscape, “Part of the reason these Welsh poems came about was because of old recordings these guys have of Paul Robeson singing in Welsh. Robeson went to Wales and was hanging out with the miners and started learning Welsh so he could be in union with them. I never knew this shit. I wouldn’t be surprised if Paul Robeson felt the same way I do about Wales. It’s so lush and green. And there’s something about Welsh people, and Irish people too, that I can relate to. Maybe its colonialism. The way they think, the way they talk, the music, the oral traditions. My friend has a theory that Black artists speak to God, and a lot of art for art’s sake doesn’t speak to anyone. And I find the mythology of Celtic cultures has a similar thing. When I speak with them, I feel super comfortable, on the same wavelength.”

Given ‘Where’ is a song about searching for a place in the world, I ask Robinson if there is a paradox here or if that longing is something that sparks creativity in the first place. “It’s the truth of the quest. And that quest could be a physical quest of travelling the world or travelling within Britain, but it’s also a quest for spiritual growth too. I find most people who are poets are trying to not get home but reach a higher state of consciousness. Those two things go hand in hand; the backdrop of nature to embark on a spiritual quest. There is some mythic truth to it, common to all cultures.”

So many cultures across the world have produced iconic figures of wandering (Moses, Gilgamesh, Odin, Ulysses, Oisín etc), perhaps there is an intrinsic connection between wandering and storytelling. Maybe we wouldn’t write at all, if we felt at home somewhere. It’s a point I put to the musician Richard Skelton, given throughout his work, there is an intense and compelling feeling of longing. Is there a sense of searching and trying to find your place at the heart of all creative endeavour as the song ‘Where’ suggests, an absence that desires to be filled?

“I’ve had a similar discussion with many artists and musicians over the years. For some people — and I include myself among them — the practice of making of art, whether it’s writing, painting, performing, making music, etc, is a compulsion. It’s a driving force in our lives, and we derive a good amount of our sense of worth and well-being through that practice. In my more pessimistic moods, I wonder whether this is healthy; whether this compulsion is a neurosis, or a coping mechanism to deal with a deeper, unacknowledged trauma. In that sense, if the trauma could be healed — if we were at home with ourselves — then perhaps the compulsion to make art would disappear.

"Of course, it’s more complicated than that. We only have to look at the art of Lascaux or Altamira, or read the ancient mythical texts, to see a larger social, communal function at work. Ideas of authorship, of individual uniqueness — of genius — have little bearing in the folkloric tradition of oral cultures. The communal sense of feeling ‘at home’ is therefore relevant here — it’s not simply a place that we derive a sense of belonging from, but also the people who inhabit it.”

A notable difference between this EP and Skelton’s other work is distance. In his previous soundscapes, the composer managed to achieve an astonishing sense of proximity within the environment, to the extent it felt like you could hear tides and weather fronts, or feel the materiality of bark, moss or stone in the music. Being unable to visit the places Robinson was travelling through and writing about, due to the pandemic, Skelton had to adapt. “My approach was more diffuse. I simply tried to think about the music more abstractly – as an atmosphere or colour field that Roger could work with. I initially sent him a few sketches, and was quite prepared for him to reject or critique them. I thought there might be a bit of back and forth before I found a form that he could work with. But it’s a credit to his abilities that he took the material I sent him and ran with it. I was astonished by what he sent back. His singing voice, in particular, was a revelation. I’d heard it before on Dog Heart City, but hearing it in its raw, unadorned form was something else. Its richness and gravitas left me unsure as to how to proceed. And, of course, then there were the lyrics. For me, his recordings could have worked as a cappella pieces, and, as a poet, I’m sure he’s used to working unaccompanied. But yes, it was a case of following in his wake, and creating a soundworld that accentuated his storytelling. This was the first time I’d worked with a vocalist in this way. I think working with Roger has also allowed me to move into new musical terrain — the ‘Never Lost Version’ of ‘Where’, for example, is unlike anything I’ve done in the past fifteen years. So, after I’d overcome my initial reticence, Roger was completely open to me splicing his vocals in different ways.”

There’s a cinematic quality to the EP with ‘Where’ summoning images of figures in the wilderness and ‘Edgcote Moor’ feeling like a mist-strewn dawn before a War Of The Roses battle. With any work of art that deals in wildness and mystery, there is a danger in unweaving the rainbow by enquiring too pedantically into its technical components, but more than that it misses the point to do so. The point is the wildness and mystery. “Those two elements are key,” Skelton acknowledges, “I’ve spoken before about being a conduit, and I’ve compared making music to dowsing for water. I’d also add that sound is, for me, somehow sentient and magical. We often think about musicians in terms of control, technique and virtuosity, but I’m interested in those uncontrolled, unrepeatable moments. The ability we have to record — and then manipulate — those moments, is a magic that our ancestors would have marvelled at.”

While it’s clear that modernity has eroded if not severed the links we have had, the world over, between language/culture and the land, it is refreshing to hear that they can be restored and expanded using the tools of modernity, rather than simply becoming mired in passive nostalgia. This inventiveness is evident not just in musical terms but in the Corbel Stone Press and the bi-annual journal, Reliquiae (ten years old in 2022) run by Skelton and Autumn Richardson, which, in Skelton’s words, is “about reconnecting and reorienting ourselves to the natural world and to the other-than-human. In the journal we position modern voices alongside ancient ones — so, in the last issue, transcriptions from the Gilgamesh Epic tablets and Egyptian coffin texts rub shoulders with contemporary poets and essayists. The idea is to remap the threads that connect us with the ancient past, and, particularly, with ways of being in the world that acknowledge our entanglement with nature. Ironically, therefore, notwithstanding our love of old books and second-hand bookstores, we couldn’t achieve half of what we do with the journal without resources like the Internet Archive, which has created an easily accessible global repository of out-of-print literatures. So, although the technological advances of industrialisation have undoubtedly accelerated our capacity to exploit the earth, those very advances have also generated a means for us to bear witness to it, to resist it, and to connect with each other through the global dissemination of knowledge and culture.”

There is no contradiction between the past that haunts this EP and the fresh territory both artists are moving into, in the same way that their differences compliment their work together. They bring their experiences and, equally, an appetite for the new, “I like the idea of not being boxed-in” Robinson notes, “Being more free to respond to things artistically.” This feeling of inspiration is not limited to the artists but extends to the listener. The origin of ‘translation’ is a ‘bringing across’, a gift from elsewhere that might change and expand our conception of the world. “Without translation,” George Steiner wrote “We would inhabit parishes bordering on silence.” Robinson and Skelton’s work, together and apart, embodies this spirit of translation, pushing deep into what had once been silence.

To listen to Roger Robinson and Richard Skelton’s self-titled EP, you’ll need to become a subscriber and sign up to the Sound & Vision tier, which is nearly 40% off for the rest of 2021. This release will be exclusively available to Sound & Vision subscribers until the Spring Equinox, March 2022.