It’s June and that means ELCAF is back at the Round Chapel in Hackney for another fine looking gathering of artists and publishers. Of the artists reviewed in this column, Jon McNaught is the artist in residence, Tim Bird is exhibiting, Ian Williams is signing on the Saturday, and Tillie Walden’s work will be available from her publishers, Avery Hill.

Having skipped a season, I can only blame the tardiness of this column on the foolhardy decision to review two particularly huge graphic novels. Whilst Jason Lutes famously took over 20 years to finish Berlin, Tillie Walden pretty much drew On A Sunbeam in about the time I’ve taken on these reviews, so maybe that’s not the best excuse after all.

More and more publishers are using crowdfunding to make sure there’s enough demand to cover the cost of getting a book made, which makes a lot of sense as nobody wants to put themselves in debt to print a load of comics that aren’t going to sell. ShortBox have been doing this, most recently (and very successfully) for an art book by Choo, which has made three times the target at the time of writing. 2d cloud have recently launched one that’s a little different. Themed bundles from their back catalogue are available as well as a box of new releases, so if you’re looking to get your hand on some weird and wonderful new comics or some of their older releases, do check it out. It could definitely do with some support over the last few days.

Tillie Walden – On A Sunbeam

(Avery Hill)

Tillie Walden’s On A Sunbeam first appeared as a web comic at the tail end of 2016 and the beginning of 2017. For those who prefer to turn the page rather than endlessly scroll, Avery Hill’s beautiful hardback is the edition for you. A book cannot conceal its size the way a website can, and this thing is huge. It’s remarkable that anyone can produce this much work in so little time, regardless of quality, but we have been here before, and must note once again that Walden is a prodigious talent with a staggering work ethic.

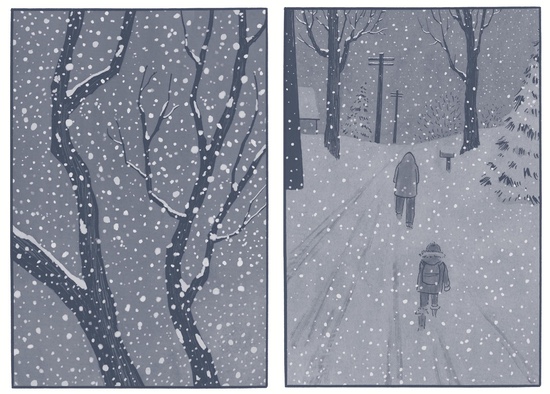

On A Sunbeam’s parallel narratives give us past and present, helpfully washed in different colour schemes in case we’re not paying attention, until the backstory is complete and the two strands can converge. With longer books there’s sometimes a fear that it can take a while for the reader to find their feet, particularly if it starts in medias res. Walden’s gift is that she creates such compelling characters and interesting settings that within the first few of these 500 pages you’re hooked and don’t want to stop reading. This is the sort of book that you need to force yourself to slow down with, to savour the storytelling.

It’s a science fiction love story, but very different from much of either genre. You can see traces of the architecture from The End Of Summer, but enhanced here by colour. Space travel is achieved in beautiful organic, piscine spaceships rather than the more traditional things that look quite like a penis. The book features exclusively female and non-binary characters, and there’s a strong thread of loyalty to your friends, of accepting them for who they are regardless of the consequences. Indeed, one character for whom chosen pronoun use is just too much effort is left in no doubt that she does not get to decide what is important for other people.

This is a fantastic comic, the best yet from an artist who just keeps improving, and shows just how hard other publishers need to work to have even a vague hope of keeping up with Avery Hill’s current output. I can’t imagine anyone being disappointed by this. Pete Redrup

James Sturm – Off Season

(Drawn & Quarterly)

A sombre book with a grey palette that perfectly matches the tone, Off Season charts a bleak period in the life of the protagonist as he struggles with pretty much everything. Estranged from his wife and sharing custody of two young children, Mark (represented, like all the characters, as an anthropomorphised dog) finds himself in an unwelcome employment situation. He’s had to sell his truck to afford the apartment he has moved out to, and this has cost him his independence as a contractor and puts him at the mercy of working for an unreliable boss, who often claims to be busy and unable to pay at present while his social media indicates otherwise.

The book also plays out over Bernie Sanders’ failure to secure the Democratic presidential nomination, the Trump campaign and surprise election and his early presidency, with most of the characters seeming to have been Bernie supporters. His wife Lisa is now volunteering for Hillary, supported by the daughter, just old enough to develop political awareness. Personal dramas are writ larger, however, and it is obvious that Mark is depressed, and out of control in both his working and family life. He wants to do the right thing by his children and his wife, but his anger and sadness mean he can’t quite bring himself to do what he knows he should. Relatively trivial parenting failures such as not knowing which jam his son prefers further lower his feelings of self-worth. Sturm is a gifted cartoonist, with brilliantly expressive canine faces. One chapter runs two contrasting narratives, the images showing him playing a game called Hungry Giant with his children, while the text reflects on his own childhood and brother, and his separation and meditation and how he thinks the process will go, a particularly effective technique.

An account of a straight white American male, there will be people for whom this is not a story they have any interest in hearing. However, there is certainly more to this. The changing economy and eroded workers’ rights, the shifting political landscape and obvious struggles with mental health are issues that cut across race and gender, although they are also issues being explored by a wide range of cartoonists. Sturm certainly isn’t taking the MRA route here, and where there is redemption Lisa usually comes off as the driving force and the bigger person. Off Season is both the name of a chapter in which Mark takes his children to a seaside resort and finds nearly everything is shut, and cold, but also the idea that the period depicted in this book is an off season in his life, and that normal service will be resumed. Despite the melancholy tone this is a sensitive and ultimately positive book constructed with immense skill. Pete Redrup

Ian Williams – The Lady Doctor

(Myriad Editions)

Although there are those among us who regard expertise as something to be suspicious of, there is much to be said for an author who knows what they’re talking about. As a GP, Ian Williams is certainly well informed about the work of a doctor, and the fact that he is an excellent writer and cartoonist at the same time makes for a very appealing package. The Lady Doctor follows on from his previous (and very good) graphic novel The Bad Doctor with some character overlap. Dr Lois Pritchard does not fit the stereotype of someone whose concern with good health starts at home. The pressures of work are certainly one reason why she drinks heavily and smokes but there’s much more to this book than what happens at the surgery.

Williams has written nuanced characters that developed well beyond our first impressions. Dr Pritchard’s arc involves the reappearance of her long estranged mother which opens up a deep seam of introspection. As one expects from a cartoonist who has worked for the NHS, and Myriad as a publisher, there’s also social commentary of the sort to enrage Daily Mail readers and those who would privatise our health service, but the book never rants. Alongside this it is extremely funny. A panel with colleagues musing about why doctors still prescribe drugs as dangerous as benzodiazepines is followed by a closeup of a promotional mug from a pharmaceutical company. A patient complains his appointment is 30 minutes late before announcing he has three problems to discuss. The man who arrives at the GUM clinic and describes a weekend of extremely unsafe chemsex then reveals he is an actuary.

Superficially simple, the drawing economically conveys the inner life of the characters through expressive faces which reveal a more confident technique than his last book. A frequently used motif is a sequence of panels, each showing the face or sometimes a body part of that day’s patients, very effective at conveying what it must be like to have your work to change every 10 minutes with almost no control over this. Williams is adept at bringing together the various strands in this book, balancing the dark with the uplifting and ensuring that we are kept laughing, and that we understand that there is nothing more important in life than the people we have relationships with. Whether you are already a fan of the graphic medicine genre or not, this excellent book is highly recommended. Pete Redrup

Jason Lutes – Berlin

(Drawn & Quarterly)

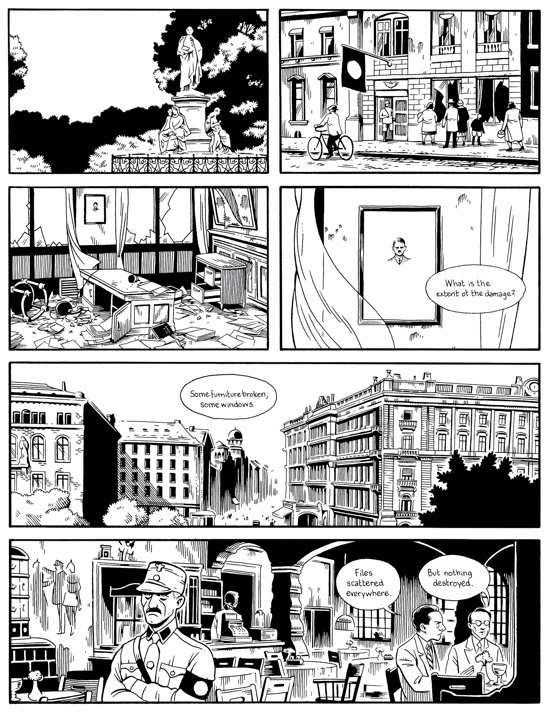

This vast graphic novel, released last year by Drawn and Quarterly, appeared on countless best of year lists, and rightly so. An account of the fall of the Wiemar republic and the rise of Nazism in Berlin, it’s hard to refute the widespread observation that Jason Lutes finished his series at a regrettably prescient time. We’ve all read thinkpieces along the lines of “I’ve always wondered how people watched fascism take power and now I think I know”, but if Berlin is in any way an accurate account, a lot more people seemed to be trying to stop it in 1930s Berlin than in present day anywhere.

The first of the 22 issues was published in 1996, and one has to be impressed at the visual consistency considering how long Lutes worked on this. His characters are carefully selected to show how the changes affected different groups in society, and include struggling families, students, journalists, musicians, the gay community and more. We see a family, the Brauns, split apart by economic hardship and then dividing upon political lines, the father taking the son and joining the National Socialists, the mother taking the daughters and eventually joining the communists. The focus is frequently on the lives of individuals rather than the bigger picture, with societal change happening in the background. It takes nearly 200 pages, but when the first "heil Hitler" comes, the impact is substantial. It’s followed by a heartbreaking death during the International Workers Day massacre in 1929, pushing family members further apart in their chosen directions.

What Lutes does here is genuinely impressive. By focusing mostly on the small picture we see how individual lives change over this period, but we are reminded that society is made up of individuals when we see the massive changes taking place in the background, and it’s the overall movement that has the greatest impact on the reader. Meanwhile, the architectural detail draws us in to the story, a fantastic diversity that matches the characters who inhabit this city. After more than 500 pages depicting five years in these lives, we are left to consider what came next, and yes, how this relates to what we see in the world today. This is well worth investing the considerable time it takes to read and reflect upon, and is very highly recommended. Pete Redrup

Jon McNaught – Kingdom

(Nobrow)

Jon McNaught’s Kingdom is a book it will be pretty easy for many of us to relate to, as it’s an account of a family weekend away in the UK. Everything you would expect is present and correct: motorway service stations, underwhelming museums with overpriced gift shops, rain, and boredom. Much like such trips, the book contains unexpected moments of transcendence as the skilfully crafted rhythms draw us gently through the narrative.

The family here consist of the mother, a teenage boy and a younger girl. This dynamic means that what appeals to one person is unlikely to appeal to all. McNaught evokes the tedium of family holidays when you’re a teenager, not interested in the same things as a younger sibling, or indeed, in being with your family at all. To make matters even worse, there’s no phone reception. Pages of tiny, repetitive panels evoke the feeling of time stretching out impossibly, a boredom so stultifying as a teenager that would feel impossibly luxurious as an adult.

There’s considerable variety in page layout, and this is the heart of the book’s strengths. Some pages have 35 panels, such as when the boy is watching TV with his family in the caravan. However, when he then goes outside to find the one spot where his phone can get a signal, we get much larger panels as he scrolls past social media posts and memes, signifying that they are much more exciting for him. McNaught is an expert in the show-don’t-tell approach, and many pages have no dialogue at all, the only words being the diegetic sounds of the various locations. It’s an excellent approach, impeccably performed, and Kingdom is a very fine book. Pete Redrup

Tim Bird – Asleep In The Back

(Self-published)

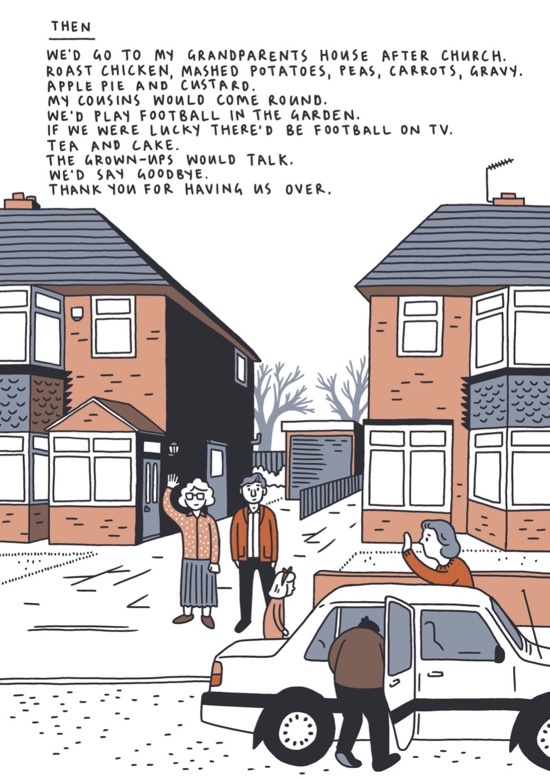

Journeys are a recurring theme in Tim Bird’s work, from his Grey Area series to smaller pieces such as Membury Services in the 10th Dirty Rotten Comics anthology. Forgoing heavy dialogue for a quiet sense of reflection, his books seek to transport us both physically and temporally, and Asleep In The Backis unmistakably a further iteration of this series.

Bird taps into a nostalgia that is both personal and universal, reflecting on the car journeys of his childhood as his family visited grandparents, sitting in the back of the car with his sister, and then brings us to the present day as his own children are the ones asleep in the back. With his distinctive representational style, lettering and colouring Bird creates a comforting, instantly recognisable world for anyone who has sat in the back or the front for a family road trip.

One of Bird’s real skills as a cartoonist is the way he can take his own experiences and make them feel like ours, whether it is forming and refining his own musical tastes in Rock And Pop or reflecting on our childhoods and travel. Asleep In The Back is simple, sweet, personal and very easy to connect with, a quick read you’ll want to return to. It’s available from his website, and almost certainly in Gosh! Comics as well.Pete Redrup

Gareth Hopkins Petrichor

(Good Comics)

You will cry, you will laugh, you will glimpse eternity.

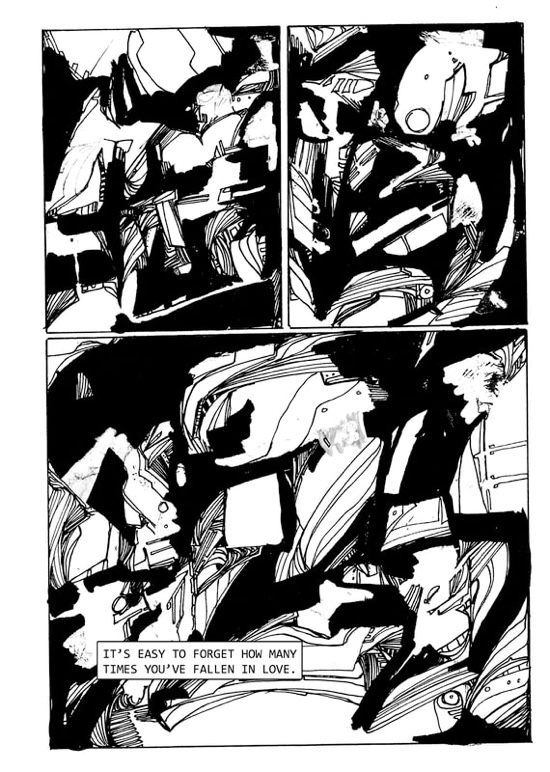

You may remember I reviewed Gareth’s The Intercorstal 68 back in June 2016. That was a thoroughly abstract comic without words but with great poetry of pattern and page design. Since then the artist collaborated with Erik Blagsvedt on a graphic novel including both abstract art and somewhat abstract text in their book Found Forest Floor with publisher 7tnbjv. Petrichor though, is a somewhat different beast.

Visually it is familiar to fans of Hopkins’ style with areas of dense detail and masterfully balanced negative space making a sort of battle dance across the pages, evolving and elliptical in their progress. He often reworks older pieces again and again in his comic work, leaving echoes visible behind the Posca pen white-outs and overlaid grids. The use of text however, is in a new direction entirely. Brave and accessible, the words here follow a rhythmic stream of consciousness that obliquely tell a story of how grief and love collide over and over again in everyday life. The word Petrichor means the smell of rain on warm dry soil, an instantly evocative concept that is true to the immediacy at play here. The way that moments of Gareth’s life are described are relatable and heartfelt. Unashamedly clichéd in places, and deeply weird in others, this snapshot of a year in grief as life goes on perfectly encapsulates those moments of realisation we get now and again that life is both those things and that is what makes it beautiful.

“There are no new ideas…” the book begins “It’s easy to forget how many times you’ve fallen in love.” As the words slowly unfold the layers of memory and experience you may fall in love again and again as well. Jenny Robins

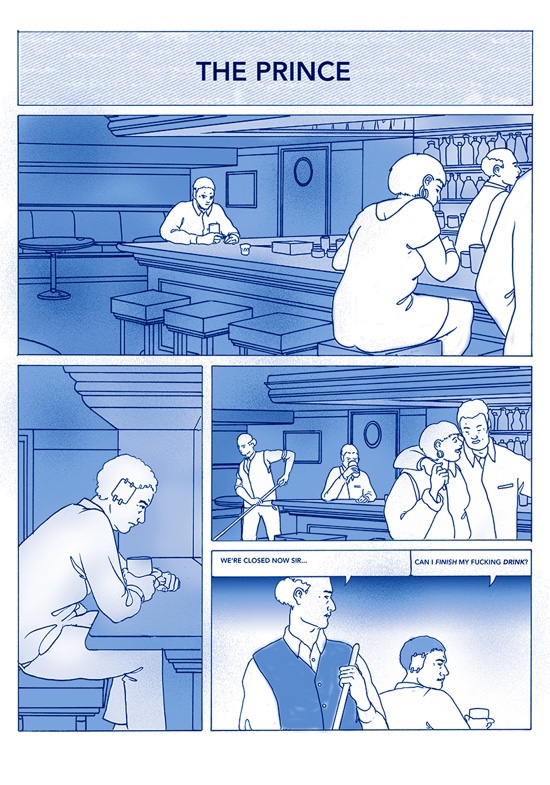

Liam Cobb – The Prince

(Retrofit)

A surreal and violent take on the classic fairy tale, Liam Cobb’s The Prince reimagines the familiar fable of the princess and the frog set in a moody world of magic realism.

Depicted in Cobb’s crisp, minimal style, The Prince follows Ada, a housewife ensnared in a loveless and abusive marriage set in a futuristic urban metropolis. Bound to a company man with barely contained anger issues, Ada begins the story as a meek victim of her husband’s demeaning behaviour.

The curious arrival of a frog encourages a series of small rebellions from Ada, building up to a dramatic confrontation with her detestable husband. Frequent attempts from her spouse to destroy the animal proof fruitless – including a memorable cooking scene – but the diminutive talisman of Ada’s independence proves impossible to ignore, setting Ada on a journey of escape from the shackles of her loveless matrimony.

We see Ada transform into a confident, sexually liberated – and occasionally homicidal – single woman, evading the predatory advances of a neighbour and would be pick-up artists with increasingly brutal consequences.

Told with crisp minimal dialogue and structured using a simple colour system – grey tones for present, blue tones for past, The Prince has enough shocks and trademark weirdness to shape well-trodden ground into something original. Rather than transforming into another useless man or white knighted savour, the frog inspires Ada into the hero of her own story, escaping a prison of domestic drudgery aided by an invincible, otherworldly guardian. Joseph Marczynski.