Twenty years ago, Bryn Jones was on a roll. In 1996, the Mancunian musician, who recorded almost exclusively under the alias Muslimgauze, released ten albums – almost one per month, a startling work rate by anyone’s standards. Listen to several in quick succession and you can hear points of continuity: the snapping, warlike hand percussion; the low drone of various stringed instruments such as the oud, buzuq and sitar; and the sampled Arabic vocals that periodically float through the mix, as if carried on the wind on some sand-clogged public address system. Yet perhaps what is more surprising, as you dig through the wealth of material Jones turned out that year is the many points of difference. Play the cacophonous live percussion and hip hop-tinged breaks of that year’s Arab Quarter back to back with the serrated minimal electronics of Azzazin, or the ghostly dub and processed field recordings of Return Of Black September, and you hear a music-maker unbeholden to formula. So strong was Bryn Jones’ drive to create, create, create that he would set light to his own rulebook for just another five yards of musical progress.

Just three years later, Bryn Jones was dead, following a quick and savage bout of bacterial pneumonia. After Jones’s death, many were drawn to reflect on the strangeness of his life, and what drove him. A loner and an introvert, he lived with his parents in a regular middle class community in Manchester, never held down anything like a conventional job, and worked ferociously at his music, funding himself off of its meagre proceeds. Thanks to the vast quantity of recordings left behind after his death, today his discography stretches far into the triple figures, and this is the sort of catalogue that people get lost in, that appears to show new intricacies the deeper you go.

One inescapable thread running throughout the Muslimgauze catalogue is a political consciousness. Jones was obsessed to the point of monomania with Arabic culture, and his work returned over and over to the Israeli-Palestine conflict, which he saw in exclusively black-and-white terms: noble Arabs battling the Zionist oppressor.

He was not religious, and never visited the Middle East (supposedly he was offered an all-expenses-paid trip to Palestine by one of the labels who released his material, Extreme Records, but turned it down on the rationale it would be wrong to set foot on occupied lands). But Jones’ distance from Muslimgauze’s subject matter lent not fuzziness, but forthrightness. “I would not tolerate anything to do with Israel… the whole people are disgusting,” he said in a 1995 interview with the industrial magazine Eskhatos.

Was Bryn Jones an anti-Semite? You might argue he’s talking about the state of Israel there, not the Jewish people more generally – although I’d argue we’re all familiar enough with that sort of dog-whistle language to know it’s not always easy to draw a clean line between the two. The interview continues in unsettling fashion. “Last night a 14-year-old boy with dynamite taped to his body rode his bicycle into a group of Israelis and blew himself up, killing several people…” offers his interviewer. “Those things will always happen until Palestine is Zionist free,” responds Bryn. “There will always be legitimate targets.”

Despite the frightening stridency of the rhetoric, there remains something enigmatic about Jones’s work: it sounds less like a statement than a question mark. I’m drawn back to Ian Penman brilliant 2003 review of the posthumously released 2003 Muslimgauze album Arabbox: “Even the slightest, prettiest tracks here are inhabited (or inhibited) by an impossibly frail and inconceivably deep sadness – which, in truth, is hard to believe was entirely locatable in Jones’s feelings about a Middle East he never visited and so which always remained an infinitely restorable phantasm inside his head,” writes Penman. “The sadness seems much deeper and further ingrained than that, approaching pathological – almost as if the terrible dispossessed ‘birthright’ of the Palestinians corresponded, secretly, to some personal scar or shadow in Jones’s own life.”

Perhaps this enigmatic quality, in concert with Jones’ early passing, makes the content of his work more palatable, or at least allows us to hold it at a distance. We can look at the imagery used on his records – the children posing with automatic weaponry on Uzi Mahmood, album titles like ‘Vote Hezbollah’ and ‘Hamas Arc’ – and wonder what might he have made of the second Gulf War, the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan, or the rise of Daesh (for all his militancy, I have a feeling Bryn would have drawn a line at butchers of Isis – if we can take anything concrete from the artwork of records like Citadel or Zul’m, he had a great love for Islamic architecture). We can also map his music onto genres that sprung up in his wake: hear how United States Of Islam’s cobwebby, layered percussion points forwards to the tribal-tinged dubstep of Shackleton, or how the atmospheric, paranoid gloom of Veiled Sisters and Drugsherpa sketch out a blueprint of sorts for Dominick Fernow’s Vatican Shadow – not quite a Muslimgauze tribute, but certainly a project consciously operating in Jones’ conceptual slipstream.

Here, then, are reflections on Bryn Jones and his music, in the words of those who knew him, worked with him, and continue to find inspiration in his life’s work. In places, they are illuminating. In other ways, they build an inconsistent picture. Who was the real Bryn Jones? Was he a man of thin skin and deep compassion, fighting for justice on behalf of the marginalized and oppressed? Or was he a provocateur or a fetishist, monomaniacally replicating images of exotic conflict like his industrial contemporaries churned out images of serial killers or the Holocaust? Or was it, in fact, all about the music all along?

Luke Younger

Younger records enigmatic industrial music as Helm, plays in hardcore group The Lowest Form, and runs the UK DIY label Alter. A long-time fan of Bryn Jones’ work, he recently hosted a Muslimgauze special on NTS Radio.

"Part of what continues to keep Muslimgauze interesting is how the records often make you question what’s being presented to you. The music is instrumental, yet loaded with atmosphere and mystery as a result of the powerful imagery that accompanies it. Despite a lack of lyrics which would help to put across some sort of message or give the release’s ‘real’ political content, you could still tell that Bryn was serious with regards to his viewpoint and there was a fire that fuelled his music. I guess the thing that I contemplate the most with Muslimgauze is just a simple: “Why?” I’m often left wondering what his story was – why a man from Manchester felt compelled to dedicate his entire creative output to conflicts in the Middle East. I recently had a conversation about Coil, wondering why it is that when an artist dies they develop a legacy, and a special kind of respect. It is tragic in a sense because they can’t be around to enjoy it. It’s as if the very death and absence of the artist itself imbues the body of work with a potency that gets stronger over time.

The imagery used on Muslimgauze records is timeless and most people around my generation can see something both familiar and exotic in it. I have very vivid imaginations of watching the Gulf War unfold on television as a child and whenever I hear Abu Nidal it seems to perfectly evoke the horror and uncertainty I felt while watching those news broadcasts.

Due to the sheer number of albums in his discography, it’s actually quite difficult to trace any real kind of definitive chronological development. If you compare records like Maroon and Izlamaphobia which came out in the same year for instance, they sound nothing like each other. It seems likely that in the ‘90s he was submitting so many albums to labels, creating a backlog that I guess is still being cleared, or at least was until recently.

I’m a big fan of the ‘80s records with the heavy sampling and minimal electronic percussion like Kabul, Buddhist On Fire and the EPs released around then – those are some of the weirdest UK underground records of that era in the sense that there is literally no frame of reference for them and it’s hard to see where they really fit with everything else that was happening at the time. I like the late ‘80s and early ‘90s stuff, which crosses over into ambient/techno territory – even when it sounds dated there’s still something about the sound that keeps me interested. From the ‘90s, Maroon, Veiled Sisters, Return Of Black September and Gun Aramaic are essential for those who are looking for something that resembles that “dark techno” sound Muslimgauze definitely helped to inspire. I’m always intrigued by a Muslimgauze release. Even if I don’t happen to like the music on that particular record, I’ll still find something interesting about it.

JD Twitch

Keith McIvor is one half of Glasgow clubland institution Optimo (Espacio). Last March his label Optimo Trax released ‘Untitled’, a lost Muslimgauze breakbeat track which, according to Jones, was recorded in 1985. Ahead of its time? You bet.

"I must have first read about him around ‘82 but the first time I heard his music was via compilation called The Elephant Table Album in ‘83 or ‘84. His records were fairly easy to find. Virgin Records in Edinburgh had a Muslimgauze section and I used to see his albums all the time but didn’t have the funds to delve in and explore until Flajelata came out in ‘86. Shortly after that his music started coming out on Staalplaat, Extreme and Soleilmoon. By now I was living in Glasgow and there was a shop here that was really into those labels, so again they were all fairly easy to pick up. So many favourites! Off the top of my head: Abu Nidal, Zul’m, Hamas Arc, Vote Hezbollah, Betrayal, Blue Mosque, Zealot, Hebron Massacre, Izlamaphobia, Maroon, Uzi Mahmood, Azzazin, Fatah Guerrilla, Narcotic… too many!

"Staalplaat gave me Bryn’s phone number as I wanted to do a record with him, with Pan Sonic – then Panasonic – doing a remix. I’m pretty sure their remix in part inspired the sound world of his Azzazin album that same year. Initially the conversations were fairly tortuous as he was so guarded and very introverted, but I think around this time he had decided to engage with the world a little more, so once he figured out I was OK he took to calling me every now and then. He was quite intrigued by what I did for a living and knew nothing about club culture. It was through talking about that and explaining the concept of ‘breakbeats’ to him that he mentioned this track he had made many years previously that sounded like what I was talking about – which is the ‘Untitled’ track I just released.

"As he claimed not to listen to any modern music I was curious as to where he had sourced the break, and also where he sourced all the Arabic voices and sounds he used. But he was always evasive about such matters. As his working methods were so mysterious and he had few apparent influences, I have no idea how he was so adept at skipping between styles. He has so many tracks that sound like they pre-empt many later trends that it is quite astonishing, but everything he ever did has its own unique sound that could only have come from him. I truly believe he was one of the most unique, visionary and creative presences in 20th century music. One day he will hopefully be held in similar regard to other free-spirited genius mavericks such as Sun Ra.

"He was absolutely not a proselytiser in person. I only met him once when he came to Edinburgh to do a gig that myself and a friend had arranged. We kept trying to turn the conversation to the political but he would always completely avoid the topic and it soon became clear he either had no interest talking about it or preferred to have an air of mystery about it all. He was a very eccentric person; pleasant, very polite, good humoured and perfectly affable to be with, but very quiet and reluctant to talk about any aspect of himself or his work. I think it is impossible to separate the political angle from his work – though just exactly what his angle was exactly is not totally clear. I can totally understand why there is some controversy around his music. I have my own personal theories but it’s not really my place to put them forward when Bryn is no longer with us to speak for himself."

Shackleton

Skull Disco founder and pioneer of dark, tribal dubstep.

"I first heard a record by Muslimgauze back around 15 years ago. A friend of mine was involved with the Stubnitz ship where Bryn had made a couple of his rare performances and he really liked Bryn’s stuff. I do not remember the name of the record but I do remember it had a lot of vinyl scratching on it, but I wasn’t so into it at the time in any case. Anyway, it was after I put out the first Skull Disco record that people started to reference Muslimgauze in relation to what I do.

"Simon Scott of Tribe Records in Leeds was really insistent that I had to become a massive fan of Muslimgauze and burnt me a load of Bryn’s records onto CD. Simon really loves Muslimgauze and I think he saw a lot of similarities in the music that I make.

"I think you are talking about a really focussed person who knew his own sound and what he wanted to achieve. The music has personality and you can sense the drive behind what he was doing. By the same token, it is not just bloody-minded angst or aggression – there is also a lot of nuance and musicality in there. I think people with these qualities are few and far between. I cannot say that I have taken a specific musical influence from his technique and production but I do really like his phased bass sounds and the way he runs the tape into saturation. People often reference his percussion in relation to what I do but, for me, that’s only valid on a surface level – we both tend to like drum sounds outside of the traditional kick and snare kit.

"I cannot say really what draws me Azzazzin more than the other records. It has an atmosphere that is quite different to a lot of his other work and I just like to hear his music without the more established tropes. I suppose you could say that it has a particularly foreboding atmosphere without being that cliche “dark”. It has a characteristic more in the Alan Vega/Martin Rev realm in my opinion and so maybe that is why I get along with it so well.

"It is often the way with non-mainstream musicians and artists that their music becomes better known after their death. Perhaps people need time to see what the person was trying to achieve. Sometimes things relate better to a different era than to the one in which they were made. Perhaps it’s also due to his massive back catalogue. Maybe people have only just managed to get through to the end of it!"

Pharoah Chromium

The long-running project of German-Palestinian experimental musician Ghazi Barakat. A long-term fan of Muslimgauze, Barakat’s latest work, Gaza, employs wind instruments, field recordings and electronic processing to create a narrative of activity around the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip during Israel’s Protective Edge offensive in mid-2014.

"In the mid-‘80s I started hearing cassettes that were circulating, then I found an LP, Uzi, which was intriguing in its concept. Then the Berlin Wall came down, and Staalplaat opened a store in a backyard that was a hotspot for the newborn Berlin counterculture. Suddenly everybody was listening to Muslimgauze and his massive output became the soundtrack to the political news of the time – the first Gulf War, the first Intifada, the Oslo Accords, the first bombing of the World Trade Centre. I loved the radical, sensationalist titles and artwork. There was much more room for sarcasm back then: United States Of Islam, what a beautiful title for a very threatening concept for the west. But this is all becoming reality. Maybe Muslimgauze is a bit like Philip K Dick when it comes to predicting the worst-case scenarios for the shape of things to come.

"I did meet Bryn on one occasion in the mid ‘90s in Berlin. I introduced myself as a Pali and we talked about Oslo and other topics. At one point an Israeli artist and experimental musician joined in, and Bryn kind of shut off. So I had the feeling that he was being a bit dogmatic about the subject. It did remind me of Norbert Finkelstein’s rhetoric in some ways. The fact that he never visited the Middle East did seem to make it easier for him to follow his more radical approach, which is also an easy way to avoid the political realities on the ground. Of course the Oslo Accords were not ideal, and a huge mistake in retrospect. But the perspective of a Palestinian state made for high hopes, and the first years after the Palestinians’ return seemed to be moving towards the right direction on both sides. The populations seemed to be receptive. Of course that didn’t last, and the situation for Palestinians in Palestine has worsened ever since.

"My favourite Muslimgauze material is the more experimental stuff. I really like Azzazin, but I also love the really percussive stuff. As a friend recently reminded me, Bryn was an ace on the hand drums. My last release is about the war in Gaza during the summer of 2014, and there are a lot of parallels to Muslimgauze’s work in the way I chose to lay out the material. Although the subjectivity of my approach is an emotional, not a rhetorical one, I feel that neutrality is meaningless in the wake of such an event."

Simon Crab

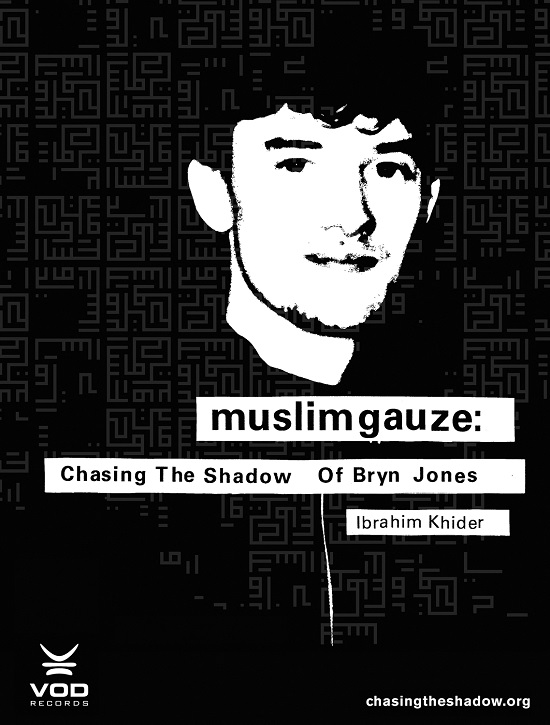

Formerly frontman of industrial synth group Bourbonese Qualk, Crab befriended Bryn Jones in the early ‘80s and released his earliest material. Crab also worked as creative director for Ibrahim Khider’s Muslimgauze: Chasing The Shadow Of Bryn Jones, a book released as part of the massive Vinyl On Demand boxset.

"I knew Bryn well before Muslimgauze, when he was going under the name Eg Oblique Graph – a much better name in my humble opinion. Bryn contacted me after I did a radio interview on Radio Merseyside, talking about the Recloose record label. He wrote to me and sent me a cassette demo of quite minimal, very clinical electronic synth music, which I liked and thought would be a good contrast with the other artists on the label. We exchanged many letters and occasional phone calls after that and I released some of his work on the first Recloose Organisation release, a compilation album and then a three track seven-inch called ‘Triptych’ in 1982 or thereabouts.

"I think I knew him better than most, though I don’t think anyone knew him ‘well’. He was extremely introverted, almost impossible to talk to – he’d probably be classed somewhere on the autistic scale these days, which probably also explains his obsessive single mindedness. I dragged him out to some gigs in Liverpool which was always quite difficult – he wasn’t exactly ‘fun’ to be around and, to be a bit harsh, he wasn’t interesting enough in his weirdness for most people to be that interested in him. I was – perhaps still am – a bit like that myself so tended to cultivate angular types like Bryn. When he did talk it was generally about his own work. He’d rarely offer an opinion on anything else. I remember him saying that he really liked Brian Eno and Throbbing Gristle… that was about it.

"I don’t think Bryn was ever ‘political’ – he didn’t have a political theory. He just reacted to events. When I knew him he hadn’t yet “got into” Islamic stuff. He was, I guess, in a similar space to a lot of industrial artists – ambiguous images of ‘oppression’, newspaper headlines, cut-ups, etc. I suspect he was motivated to shock and annoy people more than any compassion for people, and he used imagery accordingly – much in the same way as say, Whitehouse and Throbbing Gristle did but maybe less extreme. I think he got into “Islamic stuff” just because it was in the news at the time. He was naturally Conservative and quite right wing. Very anti-communist – or what he understood as ‘communism’ – and an admirer of Thatcher, which was very different to everyone else in the North West at the time. But again, I suspect a lot of this was just to be contrary.

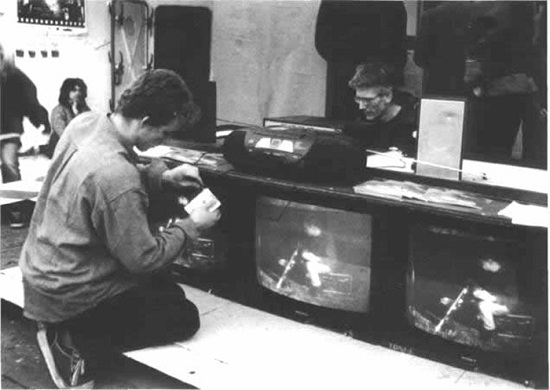

"He was extremely anxious when we got him to play at the V2 in Holland as part of the Recloose label showcase. He went into a complete meltdown at the gig. We had to play with him onstage and jam along to something we’d never heard before. Went quite well, I thought, but he was extremely pissed off afterwards – I think he thought we’d done it to humiliate him. Bryn was obsessed with the idea that we had ripped him off somehow – and I think he did this to other people as well – which is laughable. We hardly sold any Eg Oblique Graph at all, I ended up giving them away – and very few of the Buddhist On Fire LP. Nowhere near enough to cover costs. He was SURE that we’d pressed thousands of copies and sold them on the sly. I tried to reason with him for a while but eventually gave up. We never made up. It wasn’t worth the effort.

"How can I say it politely? There’s nothing ‘Arabic’ about Muslimgauze’s music apart from the fact that he nicked Arabic sounding samples. Arabic music is much, much more complex in harmonic and rhythmic structure. I think what I dislike about Muslimgauze is the loop-based sample formula. I find it lazy, boring and unimaginative – mood music. It sounds to me like a darker version of Enya. There is also a problem with cultural appropriation – nicking stuff to make your work sound cool or complex. I don’t want to come across as totally negative. I think his work was at its best, interesting and challenging. Also, just because I’m personally not that impressed doesn’t mean that it doesn’t deserve a hearing – there is obviously something there whether I like it or not. In general I think he made far too many recordings; he should have slowed down. His work would have been much better if he’d done less and had edited it more critically."

Jill Mingo

Scotland-based music publicist who worked with Bryn until his death.

"I first started working with Bryn probably in 1994, which was about the time I started working for Staalplaat in Amsterdam. They also distributed the US label Soleilmoon Recordings. I worked on probably about 15 releases, maybe more. A big reason I contacted Staalplaat/ Soleilmoon about working with them was their connection to Muslimgauze, Rapoon and Zoviet France. Blue Mosque might have been my first release I promoted on Staalplaat by Muslimgauze, but many others followed, including several limited editions and 3-inch mini CDs. I did everything on the label from 1994 to maybe 1997 or 1998. Bryn was actually just getting to his most prolific stage and Keith [McIvor, AKA JD Twitch, Jill’s then partner] was interested in doing some remixes of his music. We were wondering if this guy was some brash super-militant type. But Bryn turned out to be a very soft-spoken Mancunian.

"As far as I was aware, he enjoyed working with Staalplaat/ Soleilmoon because they were happy to release his stuff, paid him, and did tons of limited releases. In weird and wonderful packaging too – which appealed to the Staalplaat ideals as well. But Bryn was constantly trying to get more music released. He would send up cassettes sometimes. He often would have nine mixes of one song. For Keith and I, it was just wonderful. He did need someone to edit his output though. And that was something he was less keen on!

"Speaking to him on the phone, you really couldn’t meet a nicer guy. I can hear his voice now as I type this. He was far more normal and nice than anyone would probably imagine. We probably spoke a couple times a month, as he was really involved in what I thought of the new releases and was happy to do any press. Politically, he was not really that radical. He was disturbed by the problems in the Middle East and was pro-Palestinian. But it wasn’t like this was his quest for life. He loved making music. I happen to have similar views to him. Being brought up in the States, it was a very pro-Israel place. When I heard about the formation of Israel as a pre-teen in high school, I immediately thought it sounded unfair, contrived, and it really irritated me. I’ve had people try to tell me various things about the conflict and history, but from a very basic place, I think things are wrong. Bryn was similar in that respect. I never had the feeling he had some deep, analytical, scholarly approach to politics nor a radical reactionary-type vibe. I think he hoped it would cause people to question and think maybe just a little. But if they just enjoyed the music, that was fine too. He wasn’t nearly as political as you might expect.

"I am pretty sure he worked out of a studio and knew some like-minded musicians in Manchester. I know he lived at home with his parents. He clearly worked night and day on music. We were all shocked to hear about his death. He went in the hospital with bacterial pneumonia from what I understand and he just didn’t respond to antibiotics. We knew his music would live on for years because Staalplaat had enough for about 30 more releases.

Geert-Jan Hobijn

The co-owner of the Dutch label Staalplaat, who have released some 70 Muslimgauze titles.

"Bryn left behind lots of music – sometimes I think he knew there was not much time left. When he died his parents told me to take what I wanted. I declined, then they said that they would put the rest in the dumpster, so I took as many masters as I could. I have a big box, and I think there is still good material in there.

"I did not really understand his drive, but he was serious about his statements. It was no theatre or calculated position. I have seen his reaction when people suggested this – he was hurt, and still hurt the next day after. But he was no fanatic either. It was the opinion from a person in Manchester, not at all interested in religion – an opinion based what he read local newspapers. He had no intention to go to Iran, Israel or ay of the ‘hotspots’. Once we were in a restaurant of a Berlin concert hall named Podewil, where he would play that night and a big group of Israelis entered the restaurant – one floor up there was an Israeli festival. They recognized us and asked if they could join us for a pizza. He was puzzled: “Why not?” “Well, we thought, as we are Israeli…” But we all sat and talked, and they translated the interview in an Israeli newspaper. The atmosphere was friendly, and they all came to the concert later. His opinion was consistent and he did not change it when he was with me or with, say, Israelis. He would listen, and if it made sense he accepts the answer. I have read all his statements, and I do not agree with all of them but they were never racist or anti-Semitic, as people claim he was.

"My favourite Muslimgauze material is the later period. He was getting better all the time. It makes me still angry and sad that he passed away. I love the way his tracks are constructed and how he used sound samples. How he takes you with his music but then breaks the expectation. He is so in control. I miss him and his music."

Lafawndah

Half-Egyptian, half-Iranian and raised between Tehran and Paris, Yasmin Dubois makes a percussive club music employing Middle Eastern and Caribbean rhythms. ‘Town Crier’, from her recent EP for Warp Records, Tan, is inspired by her experience of returning to Iran in 2011 around the time of the Green Movement protests against President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

"I first heard Muslimgauze pretty much around the time I started working on the new EP. L-Vis 1990 brought him to my attention as something he thought I’d be into. We wrote ‘Crumb’ around then and I most definitely think that the dirtiness of the drum palette, the saturation, was directly influenced from us listening to Muslimgauze a bunch. I listened to him for a while before reading about him – that’s how I usually prefer to relate to music. It sounds so contemporary and relevant to me… his construction and sound palette of drums, how he incorporates samples. I feel a sort of unpreciousness to his tracks – there’s something very fluid and improvisational in the narrative, pre grid. In a way [it’s like] a take on John Hassell’s Fourth World music. I’d say it sounds like Western music, for sure. But with a genuine knowledge and understanding and love and curiosity for the Middle East. I don’t hear anything contrived or it doesn’t make me uncomfortable, in an appropriation way. The guy was not doing it to get any coolness credit.

"I’m really interested in the fact that he had never been to the Middle East, and that he was upfront about that. In fact it was an ethical point for him on at least two counts. On the one hand, he thought it was a failure of political imagination and empathy to argue that he had no claim to speaking about the situation in Palestine and the region more broadly; on the other, Bryn’s attitude was: Palestine is an occupied land, so to be displaced from it is somehow consonant with trying to think through it. Obviously there are all kinds of issues one could take with either of those stances, but the intensity and commitment of his drive is something to be reckoned with regardless. It would be superficial to say that Bryn’s art would be more legitimate if he’d spent time there – that perspective has turned contemporary art into a failed state of a different kind.

"The situation in the Middle East has only gotten worse since Bryn’s passing, and the need for reviving the relationship between forward music and forward politics is more crucial then ever, so his work I think is very instructive and nourishing at this moment."

With thanks to Rusted Wire of Muslimgauze.org