The tension in the packed venue was not only palpable but also worrying. The date was September 9, 1985 and the Jesus And Mary Chain were scheduled to headline Camden’s Electric Ballroom, a date that was to be the culmination of a year of riots, violence and notoriously short sets that had been left in the band’s shambolic yet thrilling wake. That trouble was going to erupt was a given. With the release of Psycho!candy still two months away, the band’s music had only been tentatively revealed via a number of incendiary singles, most notably 1984’s ‘Upside Down’ and its follow-up, ‘Never Understand’. Swathed in feedback and all-out sonic terror, the noise that fuelled the singles somehow managed to compliment the melodies that lay at their heart.

As a live band, the Jesus And Mary Chain had garnered a reputation for frustratingly compact shows that were high on belligerence and low on musical competence. The riot that accompanied their gig at North London Polytechnic in March of that year did much to seal their reputation as the enfants terribles of the British rock scene and the threat, or rather the promise of ructions at their gigs, did much to make sure that their music became a secondary concern in favour of increasingly violent and terrifying concerts.

Arriving over an hour late at the Electric Ballroom, a drunken Jesus And Mary Chain played a 15-minute set of indeterminate white noise hampered by a faulty PA that added to painful din emanating from the stage. Having staggered from the stage, it wasn’t long before cans, glasses and bottles began to rain down upon the stage. At one point the lighting rig found itself loosened from its moorings as it hung ominously over a section of the audience towards the front of the venue. Soon, the stage had been mounted with disgruntled and drunken members of the audience smashing up the band’s equipment.

“My overriding memory is of this guy standing on stage waving part of the lighting rig around,” recalls Quietus scribe Steve Jelbert. “It was simultaneously memorable and unmemorable. If you listen to a tape of it, the most interesting part of it is the riot because the music sounded fucking terrible.”

Unlike the well-organised and generally well-behaved gigs of the 21st century, concert going in the early 1980s were frequently fraught affairs. With tribalism at its height, punch-ups were a regular occurrence but there had been nothing like the mess that the Mary Chain had left behind. With their reputation preceding them, the Electric Ballroom was always going to end in tears but no one could have predicted just how violent this gig was going to be. Indeed, this writer, though a fan of the singles that had been released during the previous year, went with the intention of witnessing the trouble that was going to happen but didn’t expect anything quite on this scale. In addition the curious observers and voyeurs milling around the Electric Ballroom was a heavy contingent of squatters, people who’d dropped out of mainstream society in the wake of punk rock as well as some faces more at home fighting on football terraces rather than a gig.

“It was great standing there knowing it was going to go off,” continues Jelbert. “I’d seen them before at the ICA and that really did stink; they were totally clueless. The atmosphere at the Electric Ballroom was very odd and I felt that it was almost like a pantomime riot; if there had been custard pies then they would have been thrown at the stage. People wanted to kick off because no one really knew the Mary Chain’s music. They came out late and there was this really horrible humming noise coming out through the PA all the way through which went over the racket the band was making.”

Adding to the melee were members of the Metropolitan Police who came running into the venue as the violence increased in its intensity and with them came the realisation that things had come to a serious head. This was no longer the kind of event that generated column inches in the music press used to create a mythology around the band but a descent into darkness and uncontrollable chaos. Something had to give.

“That was the end of that period and it had stopped being funny,” bassist Douglas Hart tells The Quietus. “[Band manager] Alan McGee had sorted out body guards for that gig but I remember that on the second date of that tour, one of them got knocked out with a scaffolding pole and he quit because he couldn’t handle the heaviness of it all. And I think he’d been ex-SAS and had been one of the guys who’d gone through the window at the Iranian embassy. He was like, ‘No amount of money can make me put up with this.’”

It wasn’t until the release of Psychocandy in November 1985 that the Jesus And Mary Chain’s musical objective came gloriously into view. The hype, hoopla and carnage generated by both the band and manager Alan McGee obscured the fact that they were not only radical sonic visionaries but masterful songwriters capable of creating a classic debut album that not only captured the mood of the age but would also stand the test time while creating a new template for rock & roll.

Politically and culturally, 1985 was a watershed year. After nearly 12 months, the miner’s strike collapsed in March. Bitterly divisive, the defeat of the NUM by Margaret Thatcher’s government was an event whose ramifications are felt to this very day. The violence that had marred the dispute slipped into other sections of society. Brixton and Tottenham in London and Toxteth in Liverpool were engulfed in riots within a week of each other in the autumn. Earlier in May, pre-match rioting between Liverpool and Juventus fans resulted in the tragic deaths of 39 Italian football fans when they were crushed to death at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels, an event that was broadcast live on TV.

The pop landscape of 1985 had become increasingly grim. Daytime radio was fronted by any number of goons more concerned with their own increasing fame than the music they played and pop itself was becoming increasingly sterile. No longer a haven for outsiders and misfits, pop did its best to play safe as it increasingly relied on the promotional video becoming an end in itself. Smack in the middle of all this was Live Aid. As a genuinely altruistic event, Live Aid and its preceding single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas’ by Band Aid, can’t be faulted. An incredible event, it was watched by a global audience of some 1.5 billion people and raised in the region of £40m for the starving of Ethiopia. At the centre if it was Bob Geldof. Though his own pop career with The Boomtown Rats had come to an end, Geldof’s Herculean efforts to do the job that governments had failed to do did much to alleviate the suffering of millions.

Despite Geldof’s protestations, as a cultural event Live Aid was a stinker with huge implications for pop music. Suddenly, bands that should have been out to pasture – indeed, many of them had been – were now welcomed back with open arms, mainly by people for whom pop was little more than light entertainment. Millionaire hippies were back while others such as Queen and Status Quo who’d made money from African suffering by breaking the cultural embargo on South Africa and playing the segregated environs of Sun City were now supposed to be helping starving Africans. Their record sales were boosted as a result and none, if any, of the revenues generated made it to the starving millions. Disgracefully, the London leg featured just one black act in the shape of Sade and the whiff of self-satisfaction – witness Phil Collins jumping on to a Concorde so he could play on both sides of the Atlantic – was overbearing.

“I was very suspicious of the whole thing at the time and I still am,” Mary Chain vocalist Jim Reid tells The Quietus. “If money came out of it that went to the right people then so be it but I think a lot of people did it for the wrong reasons.

“It did create a change in people’s perceptions of what a pop could be and then it seemed alright to be an iconic figure. A lot of those bands became something that went from being a dinosaur to being iconic and a lot of people did it to sell records.

“I remember at the time, I knew people who worked at the Virgin Megastore who’d say things like Simple Minds’ albums were selling five times the amount they were the week before and you were thinking, ‘Well, are they going to send that extra money to the starving millions? How can they live with that?’”

“I remember the Live Aid thing,” adds Douglas. “We thought that punk had shaken things up; we really believed in that and we couldn’t believe it when we met people who said they were going to go to Live Aid and we’d be thinking, ‘What the fuck?’ I suppose we then tried to compete on their terms and it made us work harder. We figured that if you’d get kids listening to that kind of shit then you’d get kids hearing us. It made us more determined to be bigger.”

For a generation that was too young to appreciate punk on its first outing but had grown up on pop charts that regularly featured outsiders, seemingly sexual deviants and the kind of acts that would have parents frothing at the mouth during Thursday night’s airing of Top Of The Pops, the Jesus And Mary Chain were a godsend. Combining the sonic fury and melodicism of The Velvet Underground – a band whose resurgence in popularity during the early 1980s cannot be overstated – and the sensibilities of pop at its most classic with a surliness that suggested that anyone could do this, JAMC’s seismic arrival in pop’s barren wasteland couldn’t come quick enough. Indeed, it was precisely this kind of vacuum that galvanised Jim and William Reid into action.

“Music of that period pretty much appalled us,” says Reid as he recalls the motivating factors behind the formation of the band. “A lot of people talk about the things that we were into that caused us to form a band but it was as much the bands that we detested that caused it too.

“I remember the NME going gaga about Kid Creole & the Coconuts and we thought, ‘Fuck this!’ That just didn’t make sense in the pages of the NME. I wouldn’t say that was the turning point but round about then there seemed to be so much garbage and we thought, ‘Fuck it, there’s no one making the kind of music that I wanna buy so let’s go out and do it and make a band.’”

Jim and guitarist brother William Reid were raised in the East Kilbride of the 1960s and 70s, one of the 14 New Towns built after the Second World War to help alleviate the problems of post-war inner city overcrowding. Though portrayed in books and TV as places of awful alienation, Jim’s early memories of his hometown aren’t as bleak as they’ve been subsequently made out to be though its isolation from the centre of the pop universe proved to be another catalyst in forming the band.

“I’ve probably given East Kilbride a bad rap over the years,” he admits. “Basically, it wasn’t a bad place to grow up but it was maybe on the boring side. If you were into music, you couldn’t help but feel that the other side of the world was where it was all happening. We kinda read about punk through the NME and it seemed so remote to us; we bought the records but they seemed as if they were from another planet or something. It wasn’t a bad place but it wasn’t at the centre of things and that’s where we wanted to be. It was all right if you liked Rambo or Stock, Aitken and Waterman was your taste in music.”

Though subsequent accounts of the band’s origins paint the brothers as a pair of wastrels zombified by hours of watching too much TV, the siblings had made previous attempts of moving to England’s capital with a view to starting a band though with little success.

“Me and William had tried together and separately tried to move to London unsuccessfully,” he reveals. “We kinda went down there for a few months but we couldn’t get it together and ended up back in East Kilbride.”

Famously given a Portastudio by their father who’d spent his redundancy money on it, the Reid brothers set about recording a series of demos in their bedroom. But, as Jim reveals, the classic Jesus and Mary Chain sound came about more through accident than design.

“To be honest with you it was kind of a make-do sound,” he admits. “We were recording four-track demos in our bedroom. It wasn’t ideal and I think we had more of an orchestrated sound and there’s only so much you can do with a four-track, a guitar and a foot pedal in a bedroom and that was kind of it. We thought it would be enough to get people’s interest but it was a sketch of what we had in mind.”

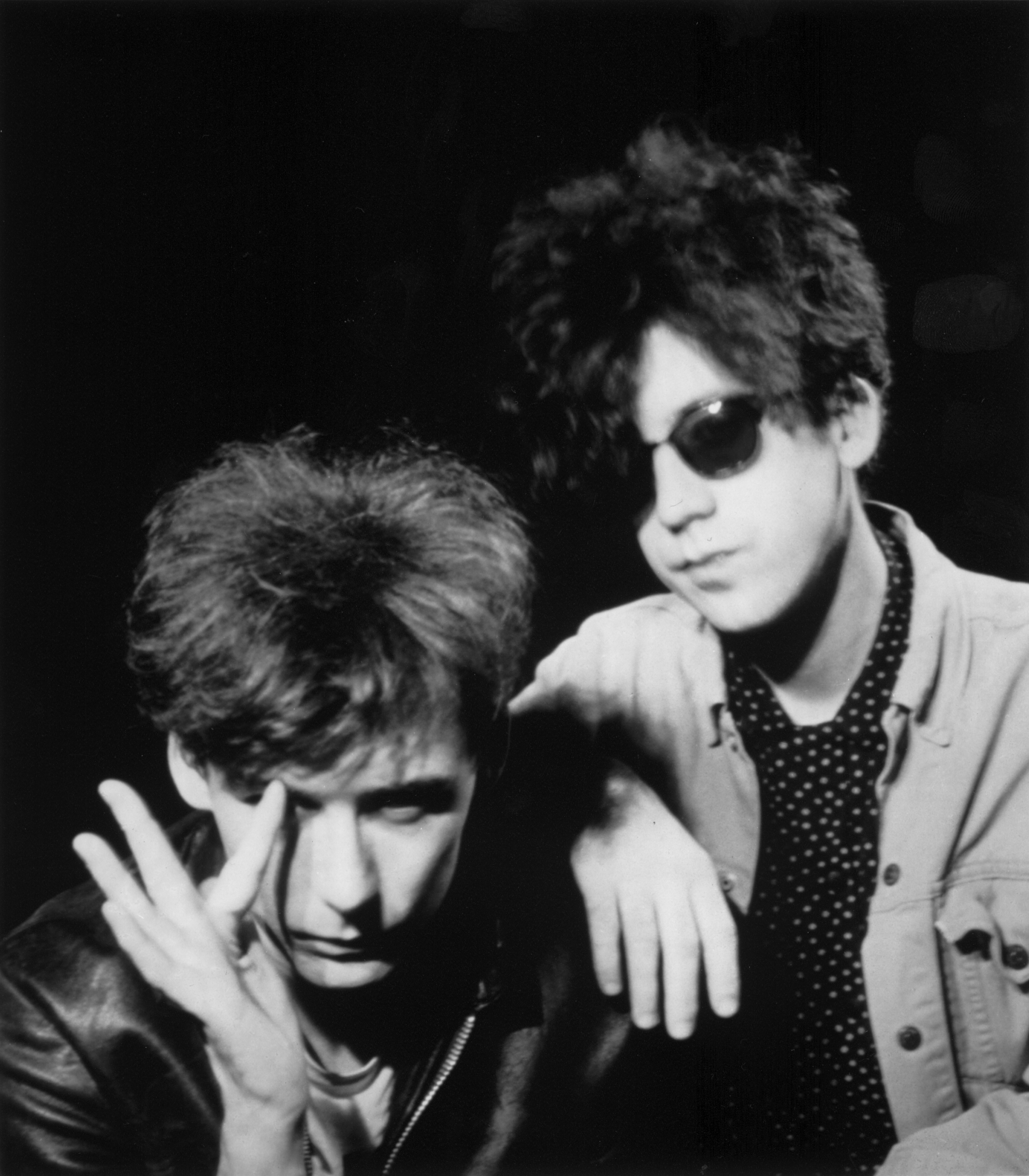

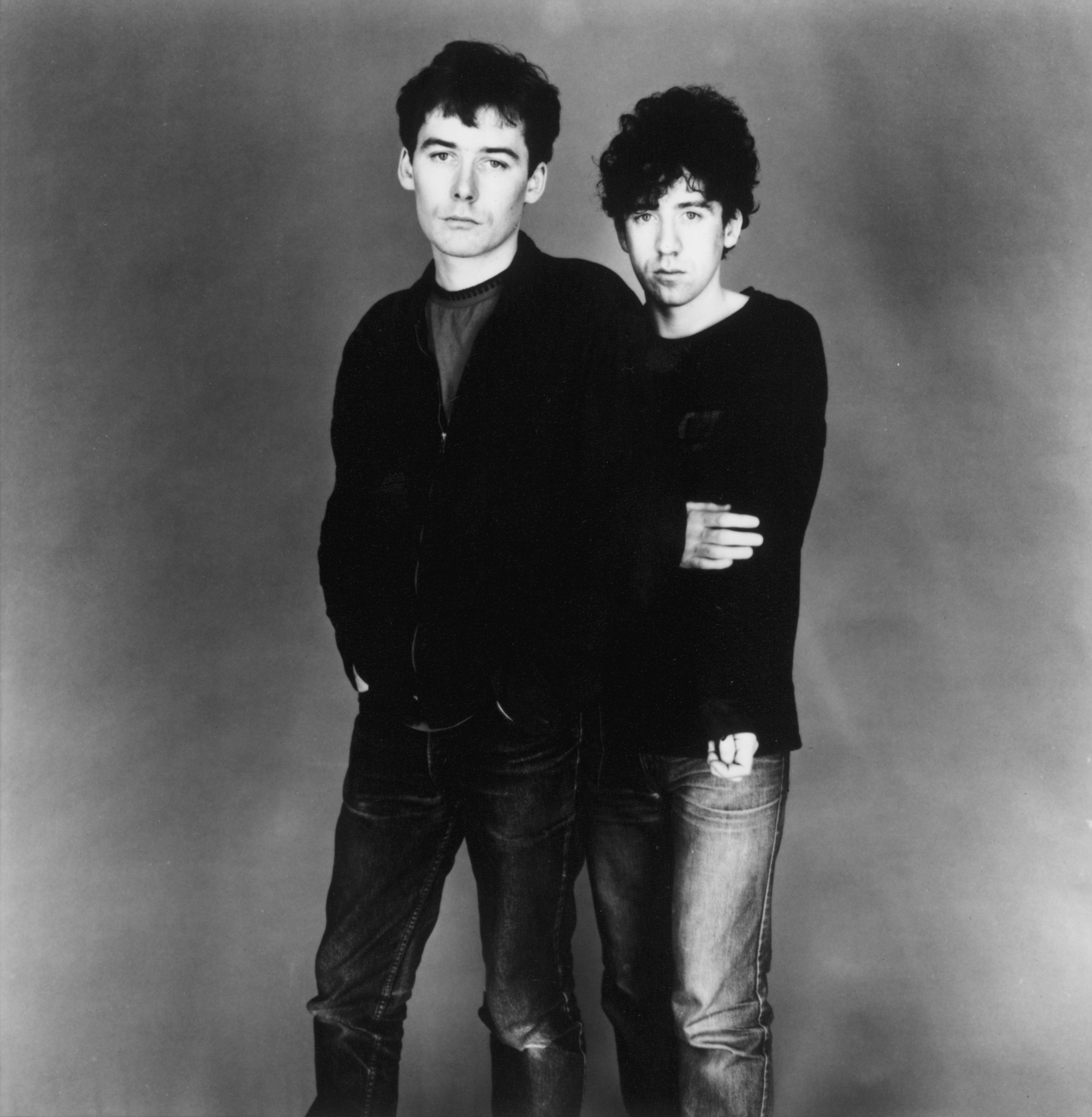

Finding kindred spirits in the provincial surroundings of East Kilbride was to prove problematic and it wasn’t until the appearance of bassist Douglas Hart that things began to take shape. Four years younger than Jim Reid, Hart shared the same taste in pop culture as the Reid brothers and despite a lack of musical proficiency, the trio soon bonded to form the nucleus of the Mary Chain.

“I used to hand around with Jim and we kind of started a band,” recalls Hart. “William was around and had his own songs but they were living in a fucking tiny bedroom and fighting all the time. So me and Jim did this thing where we did two of Jim’s songs but at this stage not much was happening.”

Though the core of the band had formed, the Reids and Hart, in common with many bands at the formation stage, still had the problem of finding a drummer.

“We befriended Douglas Hart years early simply because there weren’t that many people in East Kilbride that were into the music or literature or movies that we were,” continues Jim. “It seemed that everyone was moving in the same direction and the people that moved in the opposite direction were easy to spot. There weren’t many of them. There were me and William and Douglas but we couldn’t get a drummer. We had Murray Dalglish and he was OK but he was just a kid and he wasn’t really like us and it was never going to work.”

With the initial line-up in place and a rough sonic blueprint in place, they set about attempting to get some kind of rehearsal into place in order to work on their sound. However, this being the Mary Chain, a band built on tension and antagonism, their rehearsals offered a prescient glimpse of what was to come.

“We used to rehearse in a community centre and on Tuesday nights it’d be old ladies playing bingo and the following night the Jesus And Mary Chain would go in and rehearse,” laughs Jim. “It was about half a mile away from where we lived and we needed to get the guitars and amps down there. We stuck castors on the bottom of the amps and we’d wheel this stuff half a fucking mile with guitars piled on top. People would look out of their windows and see these skinny guys with sunglasses on pushing all this fucking stuff down the road. And we’d get there and argue for half an hour and then go home.”

Having then recorded a set of demos on their Portastudio, the nascent rock group set about conquering their next challenge: playing a gig and attempting to attract record company interest. As was common, the Mary Chain’s pleas for gigs in Glasgow went unnoticed much to the band’s extreme displeasure.

“We couldn’t get a gig in Glasgow. Nobody would give us the time of day,” explains Jim. “At the time in Glasgow there was an incestuous music scene that we were no part of; it was very difficult to get a foot in the door. They all wanted kind of white soul boy bands and we didn’t sound like that so no one would give us a gig. We were getting despondent about the whole thing and the McGee thing happened at the right time because I don’t know how much longer we could’ve kept going in the face of such a lack of enthusiasm.”

The “McGee thing” – an all-important gig at the Creation Records club night at the Roebuck pub on London’s Tottenham Court Road – was crucial to the development of JAMC and vital to setting this event up was Bobby Gillespie. Gillespie’s part in their rise is essential for it was he that first spotted their potential when given a copy of their demo tape from a Glasgow promoter who declined to put them on.

“We tried to get this gig in Glasgow and gave this guy a tape,” says Douglas Hart as he takes up the story. “We couldn’t even afford a new tape so the other side of this demo was a Syd Barrett compilation that we’d already made. The guy didn’t like us and didn’t want to put us on but he gave the tape to Bobby, more for the compilation rather than our songs. Bobby played our songs and loved them and my number was on the front of the tape. I got home from school one day and my mum said, ‘Some guy phoned you about the tape and I asked if he’d seen you and he said, "Not yet”’ and I took that as a good sign!”

He continues: “When Bobby phoned us he said, ‘I really love your tape and I’ve got a friend in London, Alan McGee.’ So the next thing, he sends the tape to Alan who got us down there.”

Even after the passing of the years, Jim Reid is still convinced that the Mary Chain secured the gig with McGee on the strength of his friendship with Bobby Gillespie rather than musical merit: “I think McGee initially did it as a favour to Bobby!”

And so, taking a fraught and tense journey from Glasgow to London, The Jesus and Mary Chain headed off to London to play a gig that would soon pass into rock & roll folklore.

“We went down there on the overnight coach with no sleep and loads of alcohol and fighting which then carried on to the stage,” explains Hart.

Arriving drunk and tired in London, the band’s spirits were hardly raised when they discovered that their debut gig in the capital was to be in the function room above the Roebuck pub. To their minds, they were set to play among the bright lights of the big city and not a down-at-heel boozer.

“Basically, it was a hot day and we were kicking around in London waiting for the time to do the soundcheck. Soundcheck? That was just a joke. It was a room above a pub and the PA was basically a stereo,” remembers Jim of the event. “We’d done the soundcheck and we’d been bickering all afternoon and at that point it was the hot weather, getting on each others’ nerves and we just started screaming and lunging at each other within two minutes of meeting Alan for the first time and he thought, Fucking hell! These guys are nuts! We started playing and we were so unmusical that he thought we were just insane.”

According to reports, the band’s set consisted of a number of cover versions including virtually unrecognisable versions of Pink Floyd’s still-unreleased ‘Vegetable Man’ and Jefferson Airplane’s ‘Somebody To Love’. With the band hideously drunk and William’s amp feeding back beyond all control, the few people that caught the show were convinced that they had witnessed some kind of joke. Believing that they’d fucked up, the band was more than surprised when an overjoyed Alan McGee offered them a recording deal.

“Alan used to get really animated when he got enthusiastic and he started screaming about ‘genius’,” continues Jim. “We thought we’d blown our chance and shot ourselves in the foot but he started going on about album deals and stuff like that. He was into it and that was good enough for us. Through that, plans were made to record ‘Upside Down’.”

Given the band’s position as a surly quartet from East Kilbride with a history of rejection, McGee’s offer was initially viewed with scepticism that soon turned to joy.

“We were naturally very suspicious of any kind of enthusiasm so we thought we’d never hear from McGee again but he was on the phone the next day. We were like, ‘Woah! This is actually gonna happen!’”

Having played a few more gigs in London, the band was booked by McGee to record their debut single at Alaska Studios in Waterloo. Only a few months ago the band had yet to play its first gig and any recording experience had been limited to making demos in a small bedroom in East Kilbride. With a limited recording budget, they were forced to record throughout the night. Despite initial reservations, the band took to the sessions with enthusiasm but struggled to capture their live sound.

“We’d work from midnight till about seven or something like that but we didn’t care; it was brilliant,” explains Jim. “The engineer that was there kept playing everything through these massive Tannoy speakers and everything sounded amazing. ‘Fucking hell!’ we thought. ‘We didn’t realise we sounded so powerful!’ We made this version of ‘Upside Down’ and when we played it back it sounded like Dire Straits! We couldn’t work out why until someone pointed out we’d been playing it through these mega fucking blow-out–the-neighbourhood speakers and they’d make anything sound like The Velvet Underground so we had to go back in and remix it.

“And we tried to do that and we did that classic thing where everybody’s in the studio saying, “Turn this up!” “No, turn that up!” so it was then decided that William and Alan would go in and mix ‘Upside Down’.”

The resulting single was one of the most thrilling rock & roll moments of the early 1980s. Though its reference points were obvious, its genius lay in mixing this heady stew together with the kind of onslaught that The Ramones had promised almost a decade earlier. Deadly in its simplicity, this was the ghost of a pre-army Elvis Presley reaching out to the living world through a vortex of terror and unrelenting feedback. Released in November 1984, ‘Upside Down’’s initial pressing of 1,000 soon sold out and reprints were quickly ordered. Selling around 20,000 copies, The Jesus and Mary Chain’s debut single put Creation Records on the map while finding itself in the No. 37 slot between The Smiths’ ‘Reel Around The Fountain’ and Cocteau Twins’ ‘Pandora’ in John Peel’s Festive 50 at the end of the year and with it came major label interest.

“It was a weird thing because one part of me thought this would always happen but when it did happen it didn’t stop you going, ‘For fuck’s sake!’” laughs Jim. “I remember we played a gig in London – just before we did this Creation Records tour of Germany – and there were quite a lot of people at that and the music papers came down. The reviews came out in NME and Sounds and Bobby was reading the reviews on our way back from Germany and I thought he was taking the piss. The NME was over the top saying how we were the greatest thing since the Sex Pistols and the Sounds one said we were the worst band they’d ever seen. You couldn’t wish for anything better! After that, record companies were beating down our doors with blank cheques.”

Before any of that was the small matter of the drummer. Always considered an outsider by the rest of the band, Murray Dalglish was fired from the group and replaced by Bobby Gillespie, a sticksman of no fixed talent but whose music tastes and attitudes were perfectly in tune with the Mary Chain.

“Bobby joining was key moment. The songs were always there and there was insanity on stage but there was always something missing,” says Douglas Hart. “There was a great moment when we kicked Murray out of the band and got Bobby to do the drums. We went to Glasgow to rehearse with Bobby and it was quite freeform and I remember thinking, ‘This has really clicked’. That was the moment when it really became amazing. He could manage to play two drums standing up and it was great because we were always asking Murray to reduce what he had. And after Bobby joined, we didn’t really rehearse but the feeling was so good and it was magical. We knew we had something.

“‘Never Understand’ was the first thing he recorded. It clicked and we then got to play cellars in Germany and wear leather trousers!”

If the sessions for ‘Upside Down’ had proved problematic in attempting to capture the band’s ferocious sound, they were to have their vision put to the test by the BBC’s engineers after they’d been invited to record a prestigious session for influential Radio 1 DJ, John Peel. To the Mary Chain’s collective mind, things had hardly progressed since the days of lab coat-wearing engineers and what could and couldn’t be done in the studio.

“When we did our first Peel session… it was a bit frustrating because the big stumbling block with the sessions was the producers and the engineers at that time,” explains Jim. “They had quite a snotty attitude towards us that we were these little kids who didn’t know shit so we didn’t record what we wanted to record. We wanted to record broken glass on one of the songs and they wouldn’t do it. We were like, ‘But we’ll break it in a bucket and it won’t go anywhere’ but the guy said, ‘No, we’re not going to do that in the studio, sonny.’ That’s the way it was then, we just had to make do.”

Though the initial Peel session of ‘In A Hole’, ‘You Trip Me Up’, ‘Never Understand’ and ‘Taste The Floor’ failed to capture The Jesus and Mary Chain’s howling fury to their complete satisfaction, the songs did reveal a masterful grasp of melody that the live shows had prevented from getting through. Clearly, a battle was raging between the basis of the songs and the instrumental packaging that embellishing them. This dichotomy would be a source of frustration for the band.

“The songs that were underneath the feedback people hadn’t really got yet. Live, it was a total sonic assault and it was difficult to pick those songs out,” sighs Jim. “And we did have that thing where we’d put on a show and we’d be like, ‘Well, what shall we try to push to the front this time? Shall we let people know there’s more to this than just a massive freak out?’ But more often than not it would be the noise that overtook everything and it was hard to keep that under control. It seemed to take on a life of its own really.”

There also remained the issue of stagecraft. The band had gone from forming to performing to recording in a very short space of time and the roles within the band had been assigned more through accident than design.

Jim continues: “The other thing was that we were kind of timid on stage and the feedback and the noise was something to hide behind. At that time, I felt very uncomfortable on stage; you know, I was just some kid who was signing on a few months earlier.

“Plus, we’d formed the band before we’d even decided who was doing what. It was never said I was going to be the singer. We always said it was going to be me or William but as I recall neither of us wanted to do it. We had an argument as to who wasn’t going to be the singer and I lost that argument. I’m not a singer in the classic sense so I needed the feedback to cover my voice on stage. My confidence level was at rock bottom.”

Riding high on the success of ‘Upside Down’, manager Alan McGee set about arranging a major label deal for his charges. Though ‘Upside Down’ had earned an impressive amount of money for Creation, McGee felt that his 20% management fee from any major deal would help sustain Creation while the band was keen to not only get themselves out of a perceived indie ghetto but were also under the impression that recording their debut album would need serious financial backing. In the end, The Jesus and Mary Chain signed with Blanco Y Negro, a subsidiary of Warners headed by Rough Trade founder Geoff Travis. Looking back, Jim Reid now questions this decision.

“We would have recorded Psychocandy on Creation if Creation had actually had any money at that time. Creation then was nothing like what it became a few short years later,” he says ruefully. “Alan was basically bankrolling a few singles here and there and all the stock was in his back bedroom, you know? It was a very small-scale operation.”

He continues: “At the time we had kinda thought, our heroes are like David Bowie and Marc Bolan and stuff like that and we wanted to be on Top Of The Pops and that we needed a bankroll behind us so we thought that it had to be a major. We thought we needed someone to spend money on the band. And the joke is that Psychocandy cost £17,000 to record – and that includes the b-sides as well as the singles – so that was peanuts really.”

Allowing himself a chuckle, he says, “With the benefit of hindsight – I mean, wouldn’t it be great to go back and speak to yourself back then – we didn’t need to sign to a major; we didn’t get a lot out of it or many benefits. Warner Brothers didn’t exactly bend over backwards to promote the Jesus And Mary Chain. They hadn’t a clue what we were all about. We just couldn’t communicate with anybody down there so it probably wasn’t the best move we’d made.”

With the deal in place, the band entered Island Studios with engineer Stephen Street who’d been making a name for himself through his work with The Smiths. Given his track record, the pairing seems odd to say the least and the attempts at recording ‘Never Understand’ came to nothing. According to bassist Douglas Hart, the sessions weren’t just to record the follow-up to ‘Upside Down’ but were originally planned to record Psychocandy.

“We tried recording it with Stephen Street at Island Studios but that was like, ‘This is not working.’ It was such a mismatch. The harshness of Island Studios didn’t suit us so we went back and recording ‘Never Understand’ in the studio we did ‘Upside Down’ in.”

Released in February 1985 on Blanco Y Negro, ‘Never Understand’ truly delivered on the promise made by ‘Upside Down’. Opening with Douglas Hart’s low bass rumble, the effect of William Reid’s grasp of studio dynamics and loops of feedback entering the fray with Bobby Gillespie’s minimalist drumming was akin to being a attacked by a swarm of bees on steroids while Jim’s laconic and reverb-drenched vocals hovered over the beautiful din with an almost delicate fragility. For those raised on 50s rock & roll, 60s girl groups, 70s chart music and the leather-trousered torch-bearers of the early 80s such as The Cramps and The Birthday Party, The Jesus and Mary Chain were the word made flesh.

The combination of their recorded work to date and growing reputation for drunkenness and violence at gigs – a gig in Birmingham in January 1985 had been cancelled by police – meant that an offer of appearing on BBC2’s Old Grey Whistle Test was offered with kid gloves and strict conditions. The show was broadcast live but for their session, The Jesus and Mary Chain had to turn up at the BBC’s studios early in the morning and pre-record their contribution of ‘In A Hole’. If the producers were expecting a fresh-faced and well-behaved band, they were shocked to find four drunken musicians rolling up at 10am.

Douglas Hart laughs at the memory saying, “For …Whistle Test, they had us in the morning to record that. We’d been up all night and it was just weird watching ourselves on telly later that night. We were all sat around this little fire with massive hangovers!”

A gloriously nihilistic performance – the band really does look as it couldn’t give a shit about being on telly – it did at least prove that the band were capable of writing memorable songs under the insistent barrage that carried them. But it was what was to happen next that sealed the band’s reputation in the wider world.

The Jesus and Mary Chain’s notorious riot gig at North London Polytechnic on March 15 has become the very stuff of legend. Oversold, overcrowded and underplayed – the band played for approximately 16 minutes – the resulting chaos saw the band’s gear trashed, the PA demolished and the arrival of police. Though Alan McGee lauded the event through a series of over-excited press releases – his claim that “…in an abstract way, the audience were not smashing up the hall. They were smashing up pop music” still manages to induces a smirk – the band themselves were now getting more than a little worried that matters were getting of hand.

Yet contrary to their reputation, they took their music more seriously than they were credited for. On March 30, work began on Psychocandy at Southern Studios in Wood Green, North London. Established in 1974 by engineer John Loder and favoured by CRASS, the role of the studio and its founder cannot be overestimated. Here, at last, the Mary Chain found an engineer who not only tore up the studio rule book but encouraged the band to indulge in their musical excesses.

“Geoff Travis suggested that we use CRASS’ studio,” says Douglas. “Not because we were fans of CRASS but because it was a totally low-key place. And it was a great sounding studio because, you know, it was like a shed in a garden and there was no pressure and it was cheap and John Loder could handle where we were coming from.

"He was the first sympathetic engineer that we worked with. A lot of the times he would just disappear. Engineering-wise, he was absolutely perfect because he’d let us try to find the sound that was in our heads without saying, ‘You can’t do that!’”

Jim Reid is equally fulsome in his praise of Southern Studios and its helmsman.

“We tried a couple of studios but it just wasn’t working. We couldn’t find the right place to record Psychocandy. We’d been to several places and they were all terrible. You’d start trying to do a mix and sorting out the guitar level and you could see the engineer looking uncomfortable with what we were doing. He be going, ‘But it’s in the red!’ and we were going, ‘Fuck that, pal! Just go for a slash!’ We just had to get away from that kind of mentality that we got in every studio in London. There was always someone in these places that just didn’t like our music.

“Southern Studios… was just fabulous because John Loder was there. He was the opposite of those other engineers; he was actually egging us on to go further. His attitude was to set the desk up and then go away. He’d just go to office and do his work. He’d have an intercom and he’d say, ‘If you have problems, just buzz me and I’ll come down and help you out.’ He did what was needed and he left us to our own devices.

“We needed someone like John. He was essential purely because he let us get on with it. We had the sound in our heads and he tried to find a way to get that on tape. He did everything he could to help us get that sound.”

Flying in the face of their increasingly fearsome reputation as belligerent drunkards, The Jesus and Mary Chain approached the recording of their debut with a focus that belied their public image. While the gigs may have ended in chaos, the band was acutely aware that this was their one chance of making a valid and coherent statement. This was make or break time.

Douglas Hart is still proud of the band’s approach: “At the time, we made that album totally sober. We used put a lot of this mad, drunken energy into the gigs with this pent-up anger that was kind of a, ‘If we don’t do this, we’re gonna die’ attitude. So when it came to make the record, we were very conscientious and not drinking and not getting wasted.”

He continues: “When it came to make the record, it was a release for us. We were a great band with great songs and we knew that if we didn’t do it right we’d probably kill ourselves. We were very hearty people; we’d slogged it out in the back of transit vans for years. It was a well-crafted record. It has a very free feeling.

“You had the chaos of the live performances but when it came to the studio, none of us had been in bands before but they were well-crafted songs and we could all step up to the mark. We knew we could do it. We struggled on the first couple of singles, to be honest, but I think that after ‘Never Understand’ we knew we could make it work in that way. The bass and the drums and the guitar would all be recorded live and then add on overdubs so it has quite a live feel.”

According the bassist, such was the Mary Chain’s almost puritanical work ethic that temptations were eschewed with an almost casual ease.

“As I say, we were very conscientious. On-U Sound were recording at Southern Studios in the evening and we were there during the day. We’d come in and there’d be all these lines of speed that they’d chopped out but we’d totally ignore all that and go get some breakfast at the Wimpy where they’d serve those weird sausages that went round the eggs. And then we’d just get on with it. Obviously, when it came to mixing we’d stay longer but not like a crazy, late night session; not at all, not at all.

“There certainly weren’t any tensions in the studio. In fact, I’d say it was a really joyful thing to do. Jim and William weren’t fighting at that time. I was there for the whole process and we’d been given a chance to make a record and it was joy to do.”

For Jim Reid, the band knew that they were in the process of making a classic and one that would not only define 1985 but also stand the test of time.

“I know it sounds big-headed, but we kinda had an idea,” he says. “We felt pretty good about the record as we were making it. We had it in mind that this was a record that would be like the kind of records that we bought; y’know, like The 13th Floor Elevators or something and you still listen to them 20 years after they were made and that’s what we were aiming for.

“We weren’t aiming for a record that comes out in 1985 and then be forgotten in 1990. We wanted to make a record that, if you heard it 25 years later, it wouldn’t sound like a 25-year-old record. And if it appealed to little spotty anoraks in their bedrooms like we were, that was good enough for us. And if there were kids scattered around the place and hearing that record and thinking, ‘I can do that!’ and they start a band then the record’s successful.”

Douglas Hart agrees with his former bandmate: “I remember we hung around William’s place and listened to it and we knew that we’d made a great record. By that time, we had a great load of songs together. It was something that we’d talked about earlier when we’d walked the streets thinking, ‘Just imagine if we could do that!’ But we nailed it and it was like a dream come true but we still didn’t know what people would fucking think of it. But there was definitely a moment when we looked at each other and went, ‘Fuck, yeah!’”

Released in November 1985, Psychocandy was an instant classic. Not carrying an ounce of flab, every song was a killer. This writer’s memory of playing it for the first was a worry that, such was the quality of side one of the album, the second side would fail to match its magnificence. A false concern. Here at last was an album that wasn’t afraid of noise or playing guitars at crotch level unlike so much of the fey music that made its name at the time; its beautiful melodies, pumping basslines and almost childishly simple rhythms were bolstered by a red-hot blast of white noise. It was steeped in the quasi-homo-erotic outsider biker imagery redolent of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising. This outsider/biker feel permeates the grooves conjuring up black leather and buckled boots straddling roaring motorbikes racing past girls called Cindy and Honey, all the while attempting to articulate teenage angst. Crucially, Psychocandy was as much a pop album as it was a rock & roll one. For the Jesus And Mary Chain, the fusing of these two dynamics was the intention from the very beginning.

“When I think back to the music that we listened to in East Kilbride, of course there were The Stooges and things like that but there was also The Shangri-Las,” says Douglas. “Those kind of disparate things gave us an elevated feeling. You know, you used to meet all these people then that were into punk but hated The Beach Boys and we found that so weird.

“We couldn’t understand why people couldn’t love both things and that combination of melody and extreme noise was so obvious to us. And they were equally as important. And so was Motown. Take ‘Just My Imagination’ – that’s three chords with really strange reverb on it. Everybody talks about The Velvets but we were more than that. Nobody really mentions the Motown influences or glam rock. You know, stuff like Gary Glitter and that were a huge thing in our life when we were young. The first thing we bought was T-Rex.

“We were totally in love with that and we wanted to be on Top of the Pops and in Smash Hits. I remember people looking at us as if we were weird for saying that and it’s amazing that we actually got into Smash Hits! And on the front cover! You look at that po-faced indie aesthetic which we hated. We were always in love with pop music.”

That love of classic pop certainly shone through Psychocandy’s 14 gems, be it the heartache of ‘Taste Of Cindy’, the Phil Spector-indebted ‘Just Like Honey’ or the glorious ‘You Trip Me Up’, a track that in some alternate universe occupied the Number 1 slot in the singles charts for several weeks. Sadly, the airwaves of daytime radio were far from accommodating to their vision and they found themselves marginalised away from the mainstream much to the band’s chagrin.

“It was more than frustrating; it was bloody annoying, actually,” Jim states “It was annoying because we wanted to have our music played on the radio and we couldn’t unless you listened to John Peel.”

Released shortly after the violence that marred the band’s gig at the Electric Ballroom and the riots that had broken out in London, Psychocandy drew a line under the chaos that had come to be identified with the band. Indeed, the band itself was acutely aware that the aggression and carnage would have to stop in favour of their increasing skills as musicians and performers.

“I always figured that if you antagonise people to that degree then you should expect a bop in the mouth,” says Jim who found himself on the receiving end of a kicking at a Nick Cave gig in 1985. “But I did worry that someone in the audience was going to get seriously injured. People would come along because they’d read that there would be a riot at the gig and you’d see some really nasty characters out there with clubs and you’d think, ‘Well, wait a minute, someone’s going to get their fucking head broken open’ and that’s when we decided that enough was enough.

“There were a few gigs and the atmosphere was such that you knew people had just turned up for a punch up. The way we dealt with it was just not to play for a while and we then said, ‘If you’re coming to our gig for a fight then you’re an idiot.’ It seemed to do the trick.”

Changes were indeed underway and by the end of February 1986 Bobby Gillespie had quit the band to concentrate on Primal Scream and be replaced by Quietus writer John Moore. Their sets became longer and more musically accomplished and with ‘Some Candy Talking’ The Jesus and Mary Chain scored their first bona fide hit before having it banned by Radio 1 under the premise of its alleged promotion of drug use.

But before all that, The Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy was declared NME’s Album of The Year, an accolade shared with Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs. (They also topped the NME’s Singles Of The Year poll with ‘Never Understand’. ‘Just Like Honey was at number two and ‘You Trip Me Up’ was at number six.) Looking back from the vantage point of the 21st century, both Jim Reid and Douglas Hart view Psychocandy’s legacy with a pride that’s several degrees apart.

“I recently met The Vaccines and they spoke really fondly of the Mary Chain and the fact that it made them want to start a band,” says Douglas with a broad smile. “It’s quite weird for me but it makes me feel really good about it. Whatever people think of our legacy, the fact is that kids are still picking up guitars because of Psychocandy. You can’t ask for than that, I think. We were driven by things we loved and if one of those bands makes a great record then you can’t ask for more.”

Jim is more circumspect than his erstwhile bassist saying, “It’s difficult for me to say. I don’t like to talk too much about what the music means to other people. We made the record and hopefully it has some significance to some people – and the more the better – but it’s up to other people to tell what they got from it.”

With a Conservative government implementing savage public spending cutbacks, unemployment and job insecurity rising and rioters taking to the streets and pop music becoming little more than light entertainment, 2011 has more than a few parallels with 1985. With this in mind, could a Psychocandy and its attendant circus happen again and is the time right?

“It probably is,” affirms Jim. “If it happened now, it would sound totally different. I think the attitude of Psychocandy was to do with not being satisfied with the status quo and trying to fuck things up a little bit. There’s always gonna be somebody who wants to do that and hopefully it’ll be different every time it happens.”

The difference could indeed be crucial. With the benefit of hindsight, The Quietus wonders what the Jim Reid of today say to the Jim Reid of 1985?

“Oh, fucking hell!” he exclaims with a laugh. “I’d probably give myself a good slap!”

And so it goes full circle to the violence once again…

The deluxe 2-CD and DVD re-mastered and re-issued editions of Psychocandy, Darklands, Automatic, Honey’s Dead, Stoned & Dethroned and Munki are out now on Edsel Records