Josh Davis, aka DJ Shadow, is a quiet but intense presence in the restaurant of a West End hotel. He looks at home among all the starched white table cloths, glinting wine glasses and imaculate steel cutlery, in his spotless, box fresh clothes and trainers. He doesn’t, to these eyes at least, look noticeably any older than he did when he was releasing early excellent trip hop singles such as ‘Lost And Found (SFL)’ and ‘In/Flux’ on Mo Wax in 1994.

His ties with the UK have always been pretty strong, given that he signed to James Lavelle’s label and even joined UNKLE for the gestation of the astonishing, if flawed, Psyence Fiction album. When people criticize Shadow for somehow diluting hip hop, they fail to recognize that before his move to London, his roots went deep in the scene given his tenure as a radio DJ in California and work with the Solesides/Quannum labels. He was an essential friend and collaborator with the likes of Blackalicious, Lateef and Lyrics Born and later a vocal supporter of the Bay Area hyphy movement.

The thing is however, that his ambition as a DJ and producer was massive, as was evidenced by his much lauded debut Endtroducing in 1996, an album that was bound to alienate hip hop purists. As everyone knows there are a couple of live vocal snippets on the album courtesy of his Oakland, Ca mates Lyrics Born and Gift Of Gab (Blackalicious), meaning that perhaps the Guinness Book of Records were a bit premature in awarding him the gong for first album constructed entirely of samples. However 90% of the disc was assembled from samples on an MPC60, with the only other sound sources being scratched in on vinyl. The resultant album was hip hop in spirit and some techniques only. He used labyrinthine programming patterns to marshall samples pulled in from the disparate sources of psych, metal, jazz fusion, hip hop, funk, afrobeat etc to create a cohesive, yet entirely self-contained sound that had little to do with either the trip hop of Mo Wax/Ninja Tune or that of Tricky/Portishead or the hip hop, electronica or alternative rock of the day.

You could write a book on Endtroducing. In fact several people have. But it still bears repeating that the arrival of this album had a profound impact on the production of music in general (for example Radiohead were audibly blown away by it) in the late 90s. And not even always in a positive way.

But despite the insane amount of attention focused on this one album, Shadow has commendably continued to push himself forward – perhaps sometimes at the expense of giving people what they want: more of the same. However, early next year he will be releasing his fourth solo album and early indications (in the form of lead single ‘Def Surrounds Us’) suggest that he is reconnecting, at least partially, with some of the production techniques that informed his debut. Loosely speaking this barnstorming single starts as a juke/crunk workout before twisting out into a byzantine pattern of drum and bass rhythms. Talking to Shadow about producing one off pieces of cover art with his kids, using guerilla marketing methods to get his 12"s into the hands of Hungarian classical music collectors and his undimmed desire to try out new production techniques means that whatever this album sounds like it is something to anticipate.

How has your recent tour been going? Have you been showcasing new material?

DJ Shadow: I completed seven or eight songs that were mixed in the studio in May and June. And of all those, all but one or two are reflected in the show. ‘I Gotta Rock’ has been going down well.

How would you describe that? And I ask because when you look at the difference between ‘Def Surrounds Us’ and ‘I’ve Been Trying’, well that’s very wide stylistically. Where does the rest of the material fit in?

DS: It’s another departure. Whenever I sit down to make music I’m trying to do something new. And while it’s true that certain collections of disparate elements can hang together better than others, most people feel that Endtroducing hangs together quite well and some people have problems with the way my last album hung together. ‘I Gotta Rock’ is fun; it’s heavy; it immediately makes the audience respond. It’s a head nodder. I think the thing that ties it all together is the work ethic, in that I try really hard to make music that doesn’t sound like anything else around. And when I make music the thing that I’m most afraid of is someone saying, “Oh, he’s just phoning it in now.” I try really, really hard to make music that’s more sophisticated… not necessarily in a music sense but in the craft, the technique, the back end. ‘I’ve Been Trying’ is very simple in terms of song writing but very complex in terms of the elements that went into it.

As a rock journalist, I’d think of ‘I’ve Been Trying’ as a psych song. Does this reflect the kind of vinyl that you’ve been buying?

DS: Erm, yeaaaaahhhhhh. It’s always hard for me to identify every single theme that goes into a body of work but another theme is a combination of urban and rural. I was working in a small cottage in Wine Country [California] in order to ahieve the level of concentration that I felt that the music was requiring. I rented this very small one room cottage which allowed me to sleep, wake up, work, sleep, wake up, work… it was in a very rural environment. I would drive around a little bit every day, taking in the mountains and the open roads and it has affected the mood of the record. The guitars on this record are rural rock. And the vocals are kind of plainer. The synth that’s in that record as well, I didn’t play it, it’s a sample from an industrial techno record from the late 80s. I just like to flash all those elements together.

On ‘Def Surrounds Us’, there is something really interesting about the beats on that record. It starts off sounding a bit like juke but ends up sounding like drum and bass. Part of your renown comes from this almost freakish attention to detail with programming. When you’re doing a track like ‘Def Surrounds Us’ is that still the case and how much has your process changed since Endtroducing?

DS: I think that as time has gone on I’ve learned that not every song needs a bombastic programming approach. Programming is always something that I grew up respecting and immediately found out the first time that I tried it exactly how difficult it is to do something meaningful and satisfying so as a result I’ve tried to back away from it. The older you get the more tasteful you become with your weight of hand. You don’t want to crush things; you want to be gentle with them. But that’s why it’s sometimes nice to do a song like ‘Def Surrounds Us’ where it was a chance for me to express myself on a programming level. And once you get into that level the process is really the same: what sounds predictable? Get rid of that. What sounds contemporary? What sounds satisfying? It’s hard, especially when it comes to anything that resembles “dance music”. It’s hard to express yourself in a way that hasn’t already been done. I don’t know how to make dance music and I never had but ‘Def Surrounds Us’ is like a bastardized amalgamation of crunk, dubstep and drum and bass but I can’t make any of those, so hopefully it becomes something unique that you would never hear on a proper drum and bass label or a proper dubstep label. It just exists in its own space.

Do you keep up with current mutations in dance music? What dubstep is becoming? What Chicago juke is becoming?

DS: Yes and no. I have name-checked dubstep a lot in the last two years because it’s one of the few genres that has incubated and developed into something good over the last ten years. There isn’t much incubation time for music these days. and when I’m pressed to chart the progress of music over the last decade, it’s one of the few shining examples I can point to. But at the same time I want to treat it with the respect it deserves. I didn’t like growing up when people would name check hip hop in a very off-handed circus way, when for someone like me it was my life. It would be like some artist name-checking punk in 1977 because they felt like they should. I’m keen to not dilute dubstep with my own very distant perception of it. Because I know it has a very fervent, passionate, hardcore base to it. If I didn’t grow up in this country, attending those clubs ten years ago I don’t feel qualified to critque it. I enjoy it and I listen to a fair share of it it but I’m not an expert.

Can you tell me about the artwork on ‘Def Surrounds Us’?

DS: On the 12”s, all of the sleeves are one-offs. When it was conceived, it was the purest way I could think of to let the music out of my hands and into the chance environment of society… in the most pure and unfucked with way. It wasn’t coming from the label, it wasn’t coming laoded with information. And if I’d had my way originally, it wouldn’t even have had my name on it. It would have been totally anonymous… It would have just let time and people’s own research and ideas determine what it was. I guess in a certain sense cooler heads prevailed and it has come out as a compromise where when you first look at it you’re not going to know what it is or who it is by. But for people like you and me who look at records every day you’re just going to stop and go: “What the fuck is this?” Because it’s removing the art from its proper context. In most cases I would have my kids doodle something and then when they got bored with it I would add my own hyper detail to it. I’m not a great illustrator but I like to draw and my dad was a graphic designer. I like spending a lot of time on pointillism and detail. It doesn’t really matter what the image really is and in fact I try and keep myself from representing anything. In some of them I’ve even added a little note that says, “Please add to the artwork before you pass it along.” We’ve added stickers on some. I like the idea that the art is never quite finished. It was inspired by a lot of other covers that I’ve seen. Obviously this kind of thing has been done before in the DIY scene and the minimal synth scene of the early 80s, so I’m not claiming to have invented the process but I intended it as the most honest and pure delivery mechanism that I could think of.

And how about placing the albums randomly in shops?

DS: It really works in the States and places outside of London primarily because you’d be hard pressed to walk into a shop in London and have it not be noticed that you’re putting a record somewhere. In the States you can walk into any charity store and no one will care what you’re doing as long as you don’t walk out with something. It just so happened that I got the first batch of vinyl when I was touring Eastern Europe, so you may stumble over some if you walk into some random shop in Budapest. I like the idea that it could be some collector of 20th Century classical music who stumbles across the record just as easily as some hipster down in Soho.

So what can you tell me about the album? You’ve said that Endtroducing isn’t a uniform record but it certainly does have a unifying mood to it. You’ve also moved further away from this and further into eclecticism and it’s five years since your last studio album, so what can we expect?

DS: There are no collaborations. Endtroducing was entirely non-collaborative. And after that I felt that I really wanted to learn from others and find out how does a guitarist record and how does a vocalist warm up and all of that stuff that I found mystifying as a fan of music. And working with Jim Abbiss on the UNKLE record was… I still work with Jim now, he mixed and co-mixed some of the songs that will be on the new album. So I was creating the collaborative process but after UNKLE I was really weary of the collaborative process because at times even though I felt that I really felt that I really stood my ground on every single possible decision on [Psyence Fiction], it was very tiring. So on the Private Press I went back to it just being me and then on my last record [The Outsider] there were a lot of collaborations again. So on this, it’s back to just me again. If I analyse Entroducing and Private Press, I think they’re the two albums that best represent what I’m about and when I think of Psyence Fiction and The Outsider, I’m thinking of two albums that I dearly love in both cases but I find somehow flawed. That’s just kind of me being honest with myself. And I think the mode that I’m in is my preferred mode and success or fail, at least I can say, “Everything that you hear I stand behind and it has my stamp of approval.” The mood, I think, is a little bit lonely and a little bit rural. There are also a lot of kinetic songs like ‘Def Surrounds Us’. But no song, in my opinion, sounds like the next. I’ve always tried to do that. And ‘What Does Your Soul’ does not sound like ‘Organ Donor’ which doesn’t sound anything like ‘Building Steam’. So while some people may take exception, I’ve always felt like I’ve tried to make albums sound like they are a universe not just a town.

I was talking to Coldcut recently about what happened to turntablism as an artform and one of the interesting things that they were talking about was how no one had really stamped their mark on the genre as a digital DJ depsite all the new tools. Do you think there is room in the future for a second wave of turntablism?

DS: My definition of turntablism is the use of the turntable as a solo instrument, so if I go and see Q Bert – who I still consider to be the best in the world – you’re there to see the Miles Davis of turntables. The Jimi Hendrix of turntables. It’s understood that you’re going to see a virtuoso performance and I think that the place for turntablism was the late 90s. It was a movement, it was a time when DJs were pushing for recognition within hip hop and I think the the general ennui that followed the big push was palpable. It showed that the amount of focus or energy was no longer necessary because you started to see DJs represented on commercials and in popular culture. In other words we succeeded in bringing DJing into the mainstream and getting it the repsect that it deserved. It’s a given now. You no longer have to have the argument, well, is this music? Which takes us back to Coldcut… it was a critical quote on one of their early records.

Ironically, the argument has now transferred from rock musicians versus DJs to vinyl DJs versus digital DJs.

DS: As far as I’m concerned DJing and turtablism are not mutually exclusive. When I first came to the UK in 1993 to do my first tour I was DJing with James Lavelle who didn’t scratch or mix at all. He would literally just play one record to the next, and the crowd didn’t care. I would maybe do a bit of mixing and a bit of scratching but it didn’t make them dance any harder. It’s the same with Giles Peterson or Keb Darge or any of the Northern Soul DJs. I can’t do what they do because that’s about knowing your audience and knowing your crate. To me it doesn’t matter to me if it’s a crate of records or a stack of CDs or a playlist of MP3s. Saying that I’m sympathetic to the purists. I still buy vinyl and I would still prefer to play vinyl where possible but then you get into all kinds of other logistical issues. I came over a year ago for a DJ Hero gig. I chose to use vinyl because I thought it was appropriate and so few people do play vinyl now that I wanted to test myself to see if I could so I played vinyl only and of course I got feedback and rumble and all these problems because none of the system was calibrated for vinyl. And then Zane Lowe came on and was using CDJs and instantly it just hits twice as loud and people are like, “Ah! Here we go!” Zane was like, “Oh man, why do I have to play next to you, you’re Shadow”, and I was like, “Man, people don’t care!” All they want to know is does it sound good and does it feel good? I respect all different disciplines in DJing, I’m not a snob.

So you don’t mind digital DJing software?

DS: No. There is one thing I will say. Serato right? You can have access to thousands of songs, so why are all the DJs still playing the same ten songs over and over and over again?

Well, I think this is a core problem for a lot dance music producers and electronic music producers as well as DJs. If you remove all boundaries from people, ironically most of them start behaving like they have very rigid boundaries in place.

DS: Yeah. In my world growing up in California, ‘They Reminisce Over You’ by Pete Rock was a tune, I still hear people drop that as a way of getting the party started now. But back then it was quite a hard 12” to come across, so playing it was kind of like, “Yeah, I’ve put in my time and effort getting this. And here it is because I know you love it.” It meant so much more then. Everyone in the room knew it was going to be a good night. But to play it on Serato to me is just so completely catering to the audience to the extent that it’s a farce. And that’s my big complaint about modern DJing. You ultimately have access to 100,000 songs so why aren’t you playing something new. I don’t want to hear ‘The Champ’ coming from your Serato! I don’t care if someone is playing something obscure or tasteful, creating an interesting body of music but otherwise I just feel like I’m being catered to like I’m a child.

Talking about keeping your set fresh, keeping the beats fresh etc, recently I made a random purchase which turned out to be great. Your old mate Cut Chemist’s Sound Of The Police mix, which was done with a pile of afrobeat records, one deck and a bunch of foot pedals. Again, I went to see Edan a few times recently and he was doing a set scratching up all of these Anatolian pop records and Turkish psych records. Do you think it’s important for the DJ to have to stretch their focus and look for beats outside the normal comfort zone?

DS: There you have cited two people who have their place in the lineage of hip hop DJing but this goes back through the history of hip hop DJing. Bambaataa was listening to Kraftwerk at the time when everyone else was limiting themselves to Sly Stone and James Brown. That right there was him being a world traveller. I think it’s fair enough to say that there weren’t too many people in the Bronx River Projects who were listening to Kraftwerk. And it’s just about looking around you and saying, “This is great but what can I add so it continues to grow and doesn’t just remain in a stasis?" That is what real DJs aspire to. Putting their stamp on the lineage before handing it over to the next person before saying, “Now how would you construct this? How would you add to this? If Cut Chemist is using one turntable and a foot pedal, that’s really cool, what can I do with that?" It’s about having an exchange of ideas and having it grow. But to me what is always really key and sometimes I think is really lost among most of my peers is bringing contemporary music into it. As much as I really like the music from the past I think it’s really, really important to bring contemporary music into it. And this is a John Peelism. I used to read his thoughts in various magazines and he would say, forget the past, the past is safe… what aren’t people embracing now? How can you make it fit into your own paradigm of what you had before and introduce it and keep things moving. I think that’s a really key concept as a DJ.

The first night out I had in London after moving here was watching you DJing at the old Blue Note Club on Hoxton Square. It was a great night out and I remember when you started your set it was with ‘Back In Black’ by ACDC and ‘We Will Rock You’ by Queen. The DJ booth was surrounded by all of these deck sharks with their little notebooks who looked crestfallen! I was wondering if this was a statement of egalitarianism; like you were saying that this music is for everyone, not just trainspotters.

DS: Yeah. I remember there was a real build up to that event. And even Karen who did press at Mo Wax – who was such a great person to be introduced into that world by – who was not usually prone to building things up, was saying, “This is a really big deal.” I was living in this flat in Hampstead in London at the time and didn’t have access to my own collection. I had gone round a few people’s houses and been second hand record shopping and I remember going out a few days before hand thinking, “There’s nothing I can do that’s going to satisfy this moment. I need to take the air out of it a little bit.” So I just went to the Music and Video Exchange on Camden Road and was just like, “I’ll have that and this.” Also I felt like I had to put people on notice. You know, “I’m not a pastiche. I’m not the record digging fanatic with the beanie that you think I am.” Well, I am… but I’m more as well.

It was such a good night. I still get a shiver down my spine if I unexpectedly hear ‘Soul Power’ by The J.B.s unexpectedly when I’m out.

DS: It’s funny you should mention that night. It was such a great time round then. I just hope that if someone is to write a book about that period, they try to capture the optimism and the open mindedness that people had. People really wanted to push back boundaries and try new stuff.

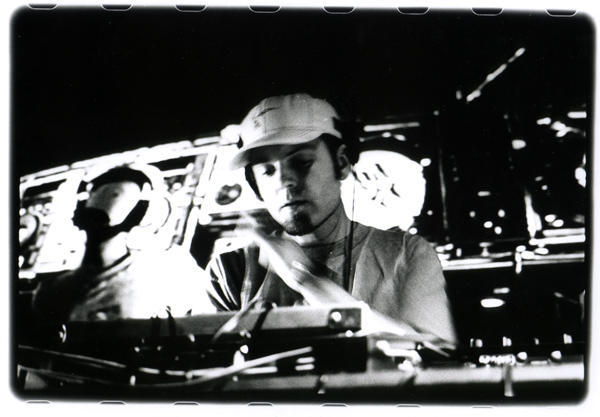

Shadow’s avatar in the new DJ Hero game