Exclusive Ninja selection by Grasscut. Scroll to the foot of the article for track list and details

All this scratching’s making me itch

So the official history has Grand Wizard Theodore in the late 1970s, sitting in his bedroom in the Bronx practising his mixing on two turntables. His mum – the woman who knew him simply as Ted Livingstone – yelled at him to turn his music down. When leaning over to knock the volume down he accidentally rubbed the record back and forward against the stylus and accidentally invented scratching.

Which is such a dumb story it almost has to be true right? No one in their right mind would make it up.

Of course manipulating vinyl to create rhythmical noise had done before. John Cage, Pierre Schaeffer, Christian Marclay and William Burroughs, had all dabbled to varying lengths with using thier ones – no twos just yet – to create noise. But importantly none of this was heading towards a flashpoint. None of this way hip hop.

Ted’s mentor Grandmaster Flash kind of took the ball and ran with it, he took the wiki-wiki back-queueing vs forward motion of scratching applied this and punch phrasing to Chic’s Good Times, Queen’s Another One Bites The Dust, Blondie’s Rapture as well as a whole bunch of ealy hip hop singles and mixed them together to form 1981’s The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel, which is still for my money one of the most excitingly weird songs to have graced the charts in the 1980s, albeit as a B-side in the UK. And scratching that something us mere mortals could access was born.

Yeah but what happened in between? Yeah, what else happened?

It never fails to amaze me how scratching never really fully impacted on the public consciousness… Well, maybe it did as much as breakdancing did for a few years but not like grafitti and rapping did full stop. If hip hop became the new rock music in the 1980s then scratching was its riffing and – after GrandMixer D ST’s work on Herbie Hancock’s Rockit – it’s lead soloing device as well.

I mean, obviously it was a big deal and whether your favourite examples of this dark art on plastic happen to be on Gang Starr’s ‘DJ Premiere In Deep Concentration, Cash Money & Marvellous’ ‘The Music Maker’ or even ‘Beat Dis’ by Bomb The Bass, it’s still possible to see that scratching never really reached its full potential.

Maybe it’s because I’m a boring nerd but I wanted more and more scratching on my records, not less and less, so what happened in the 90s was good for me but looking back not so good for scratching or hip hop. In the loosest of possible terms, as the sampler meant the DJ was gradually replaced by the producer in hip hop, wax technologists were shufffled away into their own genre, that of turtablism.

New colour, new dimension, new value

So from then on there was plenty of scratching over a strong beat to be had. Tapes of Red Alert, Mix Master Mike, Q-Bert, Shadow, Krush, Cut Chemist… but best of all was Coldcut on KISS, and their Solid Steel show. A two hour mix every Saturday night running between midnight and 2am that seemed to throw together a dizzying array of music; jazz, hip hop, acid house, techno, spoken word, classical, avant garde, drum and bass with plenty of hectic deck manipulation.

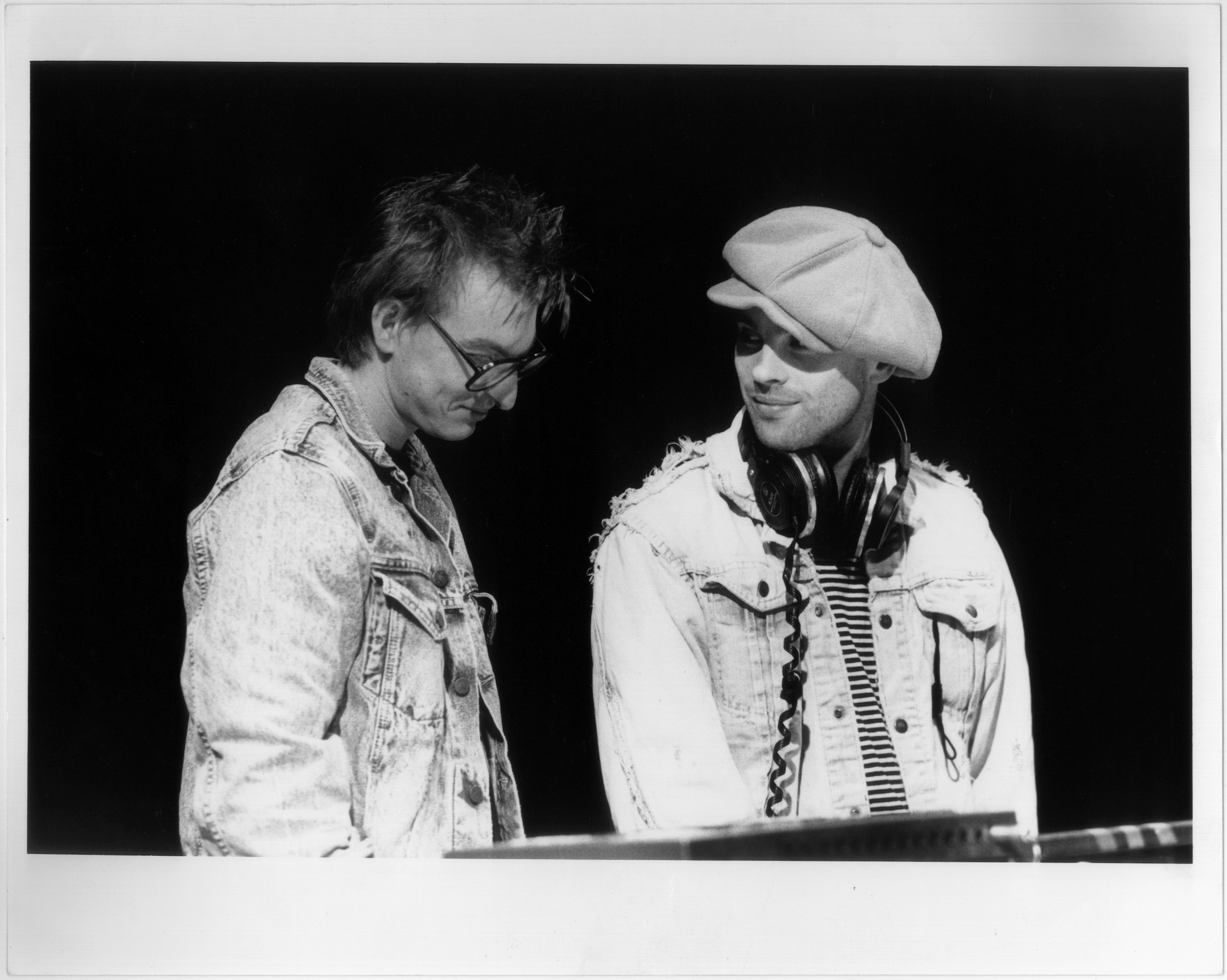

Jon More was a pirate DJ who worked in Soho’s Reckless Records in the late 1980s where he met Matt Black, leading to the pair working on the wry but revolutionary ‘Say Kids, What Time Is It?’ white label. Soon after they started working together on their Solid Steel show as they were getting Coldcut off the ground as a production duo and a club DJ team, meaning they had three fields of expression that were feeding back between each other and ultimately into the label they formed in 1990, Ninja Tune.

Among the likes of M/A/R/R/S and Bomb The Bass, Coldcut became early poster boys for emergent UK club culture in the late 80s and scored hits as producers for the likes of Yaz and Junior Reed and won renown with a forward looking remix of Eric B and Rakim’s ‘Paid In Full’. Their ‘Seven Minutes Of Madness’ mix did not go down well with the American hip hop duo or a lot of their fans but was a sublime foretaste of what More and Black would do a few years later on their peerless mix album Seventy Minutes Of Madness on the Journeys By DJ series.

Given that we’re enjoying celebrating Ninja Tune’s 20th birthday this week, we thought that Matt and Jon would be ideal people to talk to, not just about the past but where turntablism is heading in the future – something they have interesting ideas about naturally. A prize of a couple of killer Ninja CDs to the first person to spot the massive misunderstanding between me and Matt during our chat which nevertheless led us into some interesting pastures.

Hey kids, what’s happening?

Jonathan More: [laughing] Well… we’re stupidly busy with the XX phenomena. There’s the box set which we’ve managed to get together, there’s a bunch of gigs. There’s a lot of exciting music out there and it’s good that we can reflect that on the label.

Given that this is the 20th anniversary of Ninja, I was wondering how much of your decision to start the label was down to bad experiences with Arista?

Matt Black: Well, we had already started our own record label when we started Coldcut, so we realised from the start that it was better for us to control what we were doing ourselves. So initially we had just a white label, then Ahead Of Our Time, which was our first independent label and then we got into the cycle of being taken up by another label, which in turn got bought by another label… which led into the sausage machine. It was a strong motivation to realise that actually we’d made a mistake or taken a wrong turn and that we needed to blast out an escape back to being autonomous. So yeah, it was a big motivation.

JM: There were other things that added up to the event. For example Matt and I went to New York when, I think, we were signed to Tommy Boy and we met De La Soul very early in their career. We enthused vivaciously about them to the label when we got back, saying we should be working with these guys and sign them to the label. And [De La Soul’s signing to Tommy Boy] could have happened for many reasons but it was a reminder to us that not only do we have our own stuff but we have an ear for other people’s stuff that is interesting. And if you have an ear for it, don’t do it for other people, do it yourself.

What did you hope you were going to get out of it? I’m guessing you knew how much time and effort it was going to take?

MB: I don’t think of Ninja Tunes in terms of time and effort, it’s been a blast. And over the last 20-years we’ve had a great team of people working for us who have taken some of that strain from us. So I get to do what I want most of the time. But obviously it is a lot of hard work…

JM: I don’t really think about it like that. I guess it is a labour of love but I think you’d really have to ask the people who do the really hard work like hauling and stamping boxes.

MB: But there was no plan b. We were just feeling our way. We’d just found ourselves… I read one article that said Matt and Jon are the most unlikely pop stars, and it’s true. We didn’t think of ourselves like that. We were possessed by a passion for music and also a confrontational, rebellious wilfulness. It was a frustration with the establishment because we felt we could do it better. That was why we started DJing in the first place to be honest. We felt we could do it better ourselves. If we did or not, I guess that’s a matter of opinion.

If you look at some of the people that you’ve worked with such as Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys and Mark E Smith of The Fall, as well as some of the people you’ve claimed as giving you inspiration such as Throbbing Gristle and Industrial Records and CRASS and Southern Records, you can see a firm connection to the counterculture which probably first made itself known in a large way during the late 1960s…

MB: I think there’s always been a counterculture hasn’t there? My granddad was a maverick architect and jumped on the railways in the 1920s and took a trip round America and Canada with his mate, so I think there’s always been a counterculture. I think maybe it’s more visible now and certainly in the 1960s you had the psychedelic and electric rock revolution that was a big stimulus.

Well, I’m quite interested in things like this. Maybe it wouldn’t be that obvious to the casual observer but I like the deep link between a beatnik/ hippie author, an anarcho/ syndicalist punk and a hip hop DJ and I take it that you see the link between these people?

JM: Yeah, totally.

MB: I define a stupid bastard as someone who doesn’t know or care who their parents are.

JM: Seeing Throbbing Gristle was very influential on me. Just receiving albums from Industrial Music through the post was an event in itself, with all the stickers and the way it was put together. When I saw them live… I’d never seen anything like it, and the whole philosophy that went with it was something else. I was at art college at the time so I guess it chimed well with that. And the fact that questions were asked about them in Parliament after they had that exhibition at the ICA [1976’s Prostitution Show, which saw them dubbed the “wreckers of civilization” by the late Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn] and that makes them predate the Sex Pistols as far as I’m concerned. I mean they existed as COUM before that in the early 70s.

MB: I’ll say something though. Tracing those connections back… is something that came later. When I was a student just learning to mix I was inspired by hip hop. I read [William] Burroughs but I didn’t understand the connection. No one had developed or made legible this vocabulary yet. So we kind of discovered it as we went forward but looked back at the same time and untangled and traced back those connections. It was very exciting and you could almost define what we do as trying to make connections between things that don’t obviously seem connected.

Was there a Eureka moment when you looked backwards and saw the connection between cutting up blocks of sound and putting them back together and Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up technique? And this was whether it was you doing tracks like ‘Greedy Beat’ or ‘Beats and Pieces’ or Steinski or whoever?

MB: Steinski was already there. Steinski was our influence not Burroughs. Our first record was an imitation of him. I was trying to copy him. And later, I can’t remember when, someone mentioned the relationship between Burroughs and cutting up blocks of sound. It might have been someone like Mark Sinker [former editor of The WIRE]. He was in my band [The Jazz Insects] at college. He was like this academic, crazy, avant garde, jazz, sci fi head who turned me on to a lot of things. I met up with him after we did ‘Hey Kids’ and he might have tuned us into that idea.

What were the lessons that you learned from Industrial Music and which other labels did you look to for inspiration?

MB: On-U Sound

JM: Stiff Records was one that I loved. They had little things like messages scratched into the run out grooves of their records. It was quite a train-spottery thing but every record had that identity. Or even silly things like scratch and sniff sleeves. Def Jam had a very distinctive look. Rough Trade was important because it was one of the first record shops that I made a special visit to London to go to.

MB: And Mute… ‘TV OD’ and ‘Warm Leatherette’ [by The Normal, Daniel Miller’s band] were on the first 7” on Mute. I bought that when I was building a synthesizer at school and that taught me that you can do it… you can do it yourself.

JM: The thing about William Burroughs that you were talking about earlier, some of that came from the deep questioning that we got from people when sampling became news worthy.

MB: “Who do you think you are? William Burroughs?” [laughs]

JM: But one of the points I raised in one of those discussions was that the Xerox photocopying machine was a vitally important technological development [as well as the sampler or record deck] to us and this was eventually replaced by the desktop publishing [that had a similar] cut and paste function. But this was something we learned from Industrial Records and I remember that I used to spend hours on the photocopier, cutting something out, blowing it up or reducing it, sticking it down, photocopying it again… You couldn’t exist without it and Throbbing Gristle were the same, all of their promotional stuff that came in the post to you, all their flyers, this intimate connection with the band was because of the photocopier… it was very prescient. You could probably argue that this goes back to the Beatles or someone! But it was TG and their crazy newsletters that were the influence on us. With Ninja we did quite weird, cobbled together promotional material between the lot of us.

MB: Records are as much about sleeves as anything. I mean it’s a decent canvas for you to squirrel away different ideas on. You can use them to make connections. Take the sleeves of Parliament and Funkadelic for example. The amount of information they include…

JM: You think about the sleeves on albums by The Scientist or Fela Kuti, you can see how Roots Manuva has boiled that down into the sleeve for Duppy Writer.

Who was the first artist that you signed that you were really, really excited to have on board, that wasn’t yourself or someone else that you’d already been working with?

MB: [long pause] That’s really hard to say.

JM: It’s one of those things that rises exponentially as you go along. I suppose when we first started bringing artists on to the label we weren’t even sure if it was going to work because we hadn’t thought that far ahead. [laughs] 9Lazy9 was an interesting start and I think quite important.

MB: Kid Koala. He came quite randomly to us but actually uncovered a connection between what Coldcut do and what he was interested in. So he was like a lost member of the family. It was the perfect match.

Where did you find him?

JM: I went to Canada to play a rave. Jeff Waye from the company who was distributing some of our stuff in North America picked me up from the airport and the cassette was in the van. I was jetlagged, getting used to this new place, listening to this cassette. I met Eric [San, Kid Koala] the very next day, he was doing a set in the shop we were playing and he’s such a lovely fellow. So there was a connection immediately and that was when Jeff proposed forming Ninja Tune Montreal. So it was a random cassette lying in a van that sparked all that stuff. The classic heard in a van on the way from an airport scenario!

There’s something very interesting about Kid Koala, he kind of represents the end of turntablism which isn’t earnest or worthy and is about showmanship. There are too many DJs that give off this sense of ‘This is my work. I’m being very serious. Hush now.’ But if you see Kid Koala, especially when he’s doing something like Moon River, you realise that he is breathtakingly skilful but also breathtakingly entertaining. How much does this extend to the rest of your family?

MB: I totally agree with your assessment of Eric. You’re right and that’s why he’s on Ninja instead of Q-bert, you know? And that’s actually with all due respect to Q-Bert who’s actually a huge character and not as one-dimensional as some of the people you’re referring to. But Eric is in some ways linked to Coldcut with that left field, whimsical humour. But one thing that I have to take exception to is when you mentioned the end of turntablism. One thing I’ve been thinking recently is that if we’ve had the end of turntablism, then perhaps it’s time for ReTurntablism… It’s something that we’re working on at the moment. I’ve not seen anyone making this point and I find it quite interesting. What happened was the technical and wanky side of turntablism painted itself into a corner. The rest of us were shouting, ‘Scratch something different!’ And now the whole thing’s dead.

There’s still a market for it though right? I can only speak for myself but nothing gets my pulse racing like listening to a record with a strong beat having the fuck scratched out of it. Well, maybe bar watching Slayer do ‘Raining Blood’ live…

MB: Bring back jazz scratching! The crazy Miles Davis approach. We should do a competition… whoever does the best thirty second scratching solo gets £10k or something. So you’re into Slayer and you’re into scratching?

Yeah totally…

MB: Did you like Kid Koala’s thing, The Slew?

Yeah, it was wicked.

I grew up listening to heavy metal and alternative music in the 80s but all through the 90s I was into dance music and I couldn’t bear to listen to guitar music.

JM: It’s interesting because Jeff from Montreal is a big heavy metal fan.

MB: I think there’s a definite kinship there. I’m really into guitar sounds… they are the best sounds to scratch. It has a heavy transience.

I guess there’s something to be said about that Rick Rubin, LL Cool J, Run DMC sound and the kind of breaks that DJs were getting from ‘When The Levy Breaks’ or ‘Johnny The Fox’.

MB: Yeah. All of those records were a big influence on us. Rock Box by Run DMC, which although not a great, great record, it had a great idea. I realised the power of this when we were doing ‘Bits And Pieces’ with a Led Zep drum break with Ted Nugent and Grand Funk Railroad. The Chemical Brothers said that was the first big beat track and in some ways… putting rock and hip hop together… we were there. It was a good fit. You know that song we did with Mark E Smith, ‘(I’m) In Deep’? Well, that was all Deep Purple. The wah wah guitar over an acid house track with Deep Purple.

Talking about ReTurntalbism and ‘Beats and Pieces’ as you were earlier… 1996/7 was a killer year for Coldcut/Ninja Tune. Stealth [Ninja Tune club night at the Blue Note] was on fire. You’d just released my favourite ever mix tape, 70 Minutes Of Madness and you’d also released ‘More Beats And Pieces’ as a single. It felt at the time that you’d reached the outer limits of what it was possible to do with four turntables and two mixers. How much was this a fair assessment and do you sometimes think, ‘It’s time to have another crack at moving the mixing forward’?

MB: To put it simply: we are going to do another one. Your question is on point because it’s not just the fans who have been asking, ‘Is there life after Journeys By DJ but we’ve been asking ourselves that as well. So yes, we are going to do another mix but it’s a bugger because whatever mix we do will instantaneously compared to the JDJ one. But that was [capturing] a moment and hopefully some of the more open minded heads will be able to apply a different set of criteria to what we do next. But we are working on a new mix. And as for ReTurntablism there is room that is available to explore. I think we invented the term Digital Jockey and the idea that the skills of the 20th Century using turntables could be updated… and that has happened with Serato and time coding devices but I don’t feel that anyone has really come out and nailed it though. There’s a guy Ean Golden who runs a site called DJ Tech Tools and he talks about controllerism instead of turntablism and he’s pretty cool. He DJs using two midi fighters which are like banks of arcade buttons. It doesn’t need a turntable. It’s an interesting approach and it’s an debate we’re having at the moment because turntables have become so iconic. When we first started you couldn’t get membership of the Musicians’ Union so we had to register as keyboard players. So there’s something here that needs exploring and that might be Returntablism but the jury’s out and we’ll have to see. Scratching is something that is really good as well but it got led down a blind alley…

JM: Someone needs to fuck it up.

MB: Some needs to fuck it up! Someone needs to get in there, give it a good kicking and give it some new juice.

I heard a live mix recently, which was Cut Chemist doing a live mix at a Letta M’Bulu concert using one deck, a load of foot controlled FX pedals and looping devices and a stack of Afrobeat records, called Sound Of The Police which was amazing. Also I’ve been to see DJs like Gas Lamp Killer and Edan using world psych and funk in the way that block party DJs used to use American funk. And then you’ll get someone like Spykidelic doing crazy extreme metal vs dubstep DJing…

MB: It’s good to hear about stuff like this going on. Yeah, I got sent a tape of Turkish psych stuff recently. Ha ha ha! That’s amazing.

Yeah, I kind of feel lucky that I’ve got labels like Finders Keepers and Cherry Stones digging this ‘world music with a strong beat’ shit out for me.

MB: Andy Votel’s doing an amazing job. Ninja Tune should be doing stuff like that because we’re diggers as well but FK is really good. We got turned on that label by our man [record dealer] in Paris from Ping Pong. That Jean-Claude Vannier album is AMAZING!

[brief interlude where we discuss Jean-Claude Vannier’s merkin on the cover of L’Enfant Assassin Des Mouches]

I shouldn’t name drop but, y’know… I was speaking to Granmaster Flash about two years ago and asked if he was bothered about the authenticity of computer DJing software. I mean he’s a very technology conscious guy as you are yourselves. I’ll ask you the same thing, do you get people coming up to you going, ‘Oh, that’s not real DJing… you have to have a pair of Technics otherwise it’s just cheating.’ And doesn’t it stick in your craw given how open minded you had to be, to be a DJ back in the day and now you’ve got boring house DJs acting the same as the Musicians Union idiots from the mid 80s? Do the enemies of progress often come from within your own ranks?

MB: Have you heard the song by LCD Sounsystem ‘Losing My Edge’? “I hear that you and your band have sold your guitars and bought turntables/ I hear that you and your band have sold your turntables and bought guitars”! Ha ha ha! [_It should be pointed out here that Coldcut did, obviously, make a Yaz record_, Ed] It’s a debate that spills over into vitriolic argument.

Ok, let me put it another way, say you are a leading heart surgeon and someone comes along to you and said we’ve invented this new procedure for heart transplants, it’s going to cut 50% off your time in theatre and it’s going to reduce the chance of organ rejection by 50%, so ultimately it’s going to save loads of lives… there would still be people who spoke out against it just because that’s human nature but you’d have to be an idiot to reject this new method just because it didn’t take the same amount of skill and dexterity as the old way of doing things right?

MB: Well, that’s a no-brainer…

JM: …but it’s a silly example…

MB: Yes. It’s a silly example.

JM: There are advantages with both methods [in DJing]. There is something about the minimalism of two turntables, even if you have a computer providing the source of the sound. It limits you to a certain palate and people understand it. A computer is a new palate in a way and has a new palate of colours so as to whether you can make a quantifiable judgement about whether or not someone is skilfull still based on that old-fashioned idea that it’s all about hand/eye co-ordination. I was in a club once a long time ago DJing off Abelton 2.1 so it must have been some time ago and I had this guys all night long in my face going ‘You’re not a DJ. You’re not a DJ. You’re not playing records. Anyone can do what you’re doing.’ I got pissed off, stopped the computer, got a microphone and said, ‘This guy doesn’t think that using a computer is DJing, he thinks that any idiot can do it. So if you don’t mind indulging him.’ I took my headphones off, handed them to him and went, ‘Here you are.’ I went and sat down had a cigarette listened to the deafening silence that was coming from him on the decks and then went back on again.

The night I saw DJ Shadow at Stealth, he was surrounded by deck sharks who had their little trainspotter notebooks out and the first two tracks he played, I think, were ‘We Will Rock You’ by Queen and ‘Back In Black’ by ACDC. He took one of them off the deck, smashed it and threw it at these guys stood round the decks with their mouths open.

JM: Well, I used to cover my record labels over to be fair. There’s no point now though because everything’s so Shazamable.

MB: I kicked over my decks once and walked out during a set because my girlfriend got busted for having a spliff.

JM: I remember we used to wrestle bouncers so we could stay on the decks!

MB: But enough of this rock and roll idiocy! I think it’s a fair question about what constitutes actual DJing now but not one that can be adequately answered.

JM: It can be answered by the floor. If the floor’s pumping; it’s DJing.

MB: Or if I’m clearing the floor! I’ve cleared many floors in my time. Sometimes you have to, so you can start again. I’ll give you an example: do the kids really care if they’re at a massive rave watching ‘insert name of massive electronic artist who commands £200k per performance here’ who have just put on a hard drive and pressed play, instead of performing live? Do they care? Of course they fucking don’t. Should they care? Yes they fucking should. Because if someone is doing it live the energy is more effective, it isn’t just a commodity. But lots of people are happy with just a commodity. And fuck them. Eat your nice McDanceBurger and be sick. I’m just trying to get on with researching what I do and fucking things up.

One of the things that we’ve not mentioned yet which was running parallel to all this going on and is still a going concern now is Solid Steel – London’s Broadest Beats, a show which used to run between midnight and 2am on KISS when it was a pirate and carried on when it went legit. I remember I had a tape that I made when I first moved down south in the mid 90s and it had this bit that featured ‘You’re Gonna Get Yours’ by Public Enemy with loads of dubby echo on it over some tweaking acid house with loads of scratching and a bass line that sounded like it was being played on a tuba…

JM: Don’t ask us what it was…

But I remember when that tape snapped I was distraught. And my girlfriend was like, ‘You can buy another one’, and I was like, ‘You… don’t… understand!’ You must have been aware how much this show meant to people, but now given the changing face of radio in the capital over the years… how difficult has it been to maintain Solid Steel over the years and what was it like when KISS got taken over?

MB: You don’t know what it’s like… necessarily. You don’t know how many people are listening. It was before the internet. You don’t know if people like it or not, you just take it on faith. A few people might come up to you or write to you but most people don’t write, you know what I mean? And in fact it was kind of lonely doing that stuff, you just hoped that people would appreciate it. And it’s only 20-years later when you find out that people hallowed those tapes. But yeah, it was a nasty shock when KISS got… when they sacked [Danny] Monassa, that was when we resigned. Because a couple of years previous to that Monassa had let the station be run out of his coucil flat. It was a very dangerous thing to do. It was a big risk for them. So when we got a licence and he got sacked, it was clear that the values had changed.

JM: There was too much reggae on the station apparently. [laughs]

MB: I remember when we released ‘More Beats + Pieces’ and it was number one in the dance chart, KISS wouldn’t playlist it. I remember we were probably about the most famous people on KISS around that time and they sent us this letter saying ‘Not suitable for KISS airplay’.

JM: But that’s a constant thing. That sort of thing hasn’t changed at all. The festivals that started life as brilliant independent affairs became comodified and sold on and sold off, with people picking bits off of it along the way.

MB: My attitude toward this is that it’s a natural process and if you want to protest about it until you’re blue in the face, then you’re probably going to die young. The best thing to do is to ignore [commodified things] but keep a wary eye on them.

JM: It’s going down through the generations now though. Strictly Kev and DK do most of it now and have apprentices to help them and it’s been handed on in the same way that DJ Food got handed on.

MB: I want to get back involved with it though and do some mixes again. Kev and DK have made it part of their musical expression and we know now that there’s a lot of love shown for it and that it means a lot to some people. There were some good trips…

The freedom as DJs to include avant garde music, classical, spoken word, soundtrack stuff… it must have been liberating.

MB: Radio’s a different environment. I think you could say, as regards our own evolution, that possibly the freedom we had on the radio led to the trip hop thing. It wasn’t just about the beat and keeping the four four, it was a different dimension, so we could take a different pace and a different set of approaches to it.

Out of the numerous vocalists, crooners, ranters, shouters, polemicists that you’ve recorded with, who was the most larger than life? My guess would be either James Brown or Mark E Smith…

JM: I think it’s a competition between those two! Meeting James Brown was surreal. I’m still not sure if I was actually there or not. We got taken to a really expensive hotel near Trafalgar Square, we were met downstairs by his hairdresser who I looked up later and found out his name was Mr Teasy Weasy. We were escorted up after being given some lessons on how to talk to Mr Brown which amounted to, ‘Don’t call him James.’ He was sitting in this big lazyboy type chair watching baseball on a massive television and singing happy birthday on the phone to one of his many nephews and nieces. We shook hands with him, he said something to us, I didn’t really understand what he said, it might have been, ‘Take it to the bridge.’ We had our photo taken with him for the cover of Blues and Soul magazine. And to this day people see the photo and think we’re standing with a cardboard cut-out.

MB: It really does look phenomenally like a cut-out. The headline was ‘They’re wanted for sampling the Godfather’ and the next week he was arrested after a high speed chase. Mark E Smith is a real character. We’ve worked with him a couple of times. We were in the studio once with a guitarist and he was going, ‘Look, he’s playing it all wrong. He’s playing it all wrong! Turn it down in his headphones… or turn it all the way up.’

JB: He was a good laugh. We had a good time with him. You just have to go with the flow with Mark. I’d imagine for a well taught, brought up in the industry, standard sound engineer he must be the devil incarnate. He does things like sing and play the cymbal at the same time. Which for separation must be a nightmare. But we gave him a megaphone and set up loads of microphones in the studio so he could wander round this massive studio in Wood Green with this megaphone just ranting away. It was great.

Have you got rhythms you haven’t used yet?

JM: [laughing] Too many, that’s the problem.

MB: You know White Noise [early electronic group featuring Delia Derbyshire]? We met David Vorhaus from that group and he said there’s white noise, pink noise, red noise – which basically has had its frequencies shifted so there’s more bass, there’s green noise which is what environmental people talk about and do you know what black noise is? Silence. That’s the rhythm we haven’t used yet.

Ninja Tune XX – Tracks Selected By Grasscut

Grasscut are a Ninja Tune allied duo, Andrew Philiips and Marcus O Dair [who I’ve just discovered is a Quietus writer!], who as well as composing film scores have worked with Baaba Maal and Neneh Cherry. They claim Robert Wyatt, Brian Eno, Kraftwerk, Vaughan Williams, Brian Wilson, WB Sebald and Gavin Bryars as influences. Sensible chaps. And here’s Andrew’s selection for your delectation:

‘Foley Versions’ – Kronos/ Amon Tobin

‘One Good Thing’ – Lou Rhodes

‘Newsflash’ – Metronomy remix

‘LA Nocturne’ – Daedelus

‘Cloudlight’ – Eskmo

‘Double Edge’ – Emika

‘Toccata’ (grasscut remix) – Jaga Jazzist

‘Woebegone’ – Fly Lo remix

‘Tomorrow’ – Jono McCleary

‘Never Mess With Sunday’ – Yppah

‘It’s On’ [cut with ‘Never Mess with Sunday’] – Roots Manuva

‘Impossible’ (Shuttle remix) – Death Set

‘Dub Styles’ (Micachu remix) [cut with ‘Impossible’] – Roots Manuva

‘Volcano’ (4Tet remix) – Anti Pop Consortium

‘Eight Sum’ – Amon Tobin

‘I’ll Let You Know’ – Paris Suit Yourself

‘Fools’ – Two Fingers

Thanks to Mat, Jon, Andrew, Marcus, James, Laura, Stevie, Robin, Charlotte, Adam and everyone else who has helped us with all our Ninja Tunes content this week