Being Brazilian in 2002 meant living in a country that promised nothing but hope. Many of us watched Brazil winning its fifth FIFA World Cup in an exciting final against Germany; Ronaldo at his peak. We saw Luis Inácio Lula da Silva become president, then the most-voted candidate in the world, elected with nearly 53 million votes – the first time a left-wing politician took power in the country. BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) were constantly in the news, forecasted to become wealthier than most of the current major economic powers by 2050. And it was also the year in which Brazilians rediscovered the joys of homegrown movies.

Brazil was cool, and great things were coming our way. For a country that is a former colony with underdog syndrome, being in the international spotlight validated our talents. We were promised change, and the future looked bright politically, economically, and culturally. Brazilian cinema bloomed in a way that it hadn’t since Glauber Rocha, the Brazilian director of Cinema Novo of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Filmmakers like Walter Salles became critically acclaimed both nationally and internationally (1998’s Central Station won the Golden Bear at the Berlinale, and was nominated for the Best International Feature and Best Actress Oscars in 1999).

City of God played a huge part in that hopeful scenario: the movie, directed by Fernando Meirelles, was one of the 11 Brazilian productions released in 2002. It also became one of Brazil’s highest-grossing films of that year: out of seven million tickets sold, nearly half of them were to see City of God – more than international productions like M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs and Star Wars: Attack of the Clones. On top of that, it was nominated for four Oscars: Director, Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, and Film Editing.

The movie adapts the eponymous and semi-autobiographical 1997 novel by Paulo Lins, set in Cidade de Deus (‘City of God’, in English), a housing complex inaugurated in 1966 that became one of the largest and most violent favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Much of the material was collected during Lins’ eight years of anthropological research on crime and the popular classes in Rio de Janeiro. The story reveals the social transformations the favela went through, from the petty crime of the ‘60s to the generalised violence and drug trafficking dominance.

The entire plot is told from the perspective of Buscapé (Alexandre Rodrigues), who introduces the audience to life in the favela. Unlike many boys he grew up with, Buscapé had the opportunity to change his reality and became a photographer – a dream that seemed possible in the original context of the movie. The 2011 study “Income Inequality in the Decade” from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV), revealed that poverty had decreased by 67.3% since the creation of the Plano Real ("Real Plan", in English, a set of measures taken to stabilise the Brazilian economy in 1994) until December 2010. According to the study, poverty fell by 50.6% during the Lula government between December 2002 and 2010, allowing for more class mobility.

Even with some reduction compared to 2021, poverty in Brazil should end 2022 above the 2012 levels. A study by Trendências Consultoria predicts that the poor Brazilian households should close the year at 50.7%. This represents a decrease in relation to 2021, when it was 51.3%, but still higher than the 48.7% of 2012. The consultancy’s long-term projections also point out that it will take seven years, until 2028, to return to the 47% of 2014, the lowest in the survey’s historical series, which began in 1999.

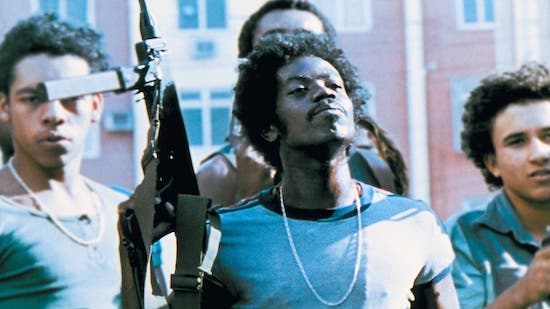

But the movie also focuses on the kids who stayed – a group of boys is influenced by three amateur thieves, the “Trio Ternura”, who introduce them to the world of crime. Influenced by this situation, Zé Pequeno (Leandro Firmino) grows up in the midst of violence until he becomes one of the main names in drug trafficking in Cidade de Deus. From the beginning, the film highlights the clashes between drug dealers and the police, which also affect the population that is not involved in drug trafficking.

What turned City of God into such a success was partly the way it depicts the motivations behind the crimes. It raises the issue that criminality is complex, and it’s often a way out for those who lack social and economic opportunities – how crime offers a means to social ascension, status and power within the favela. It’s not a character flaw – and although that might seem like an obvious perspective, it’s worth pointing out that Brazil is a country where 60% of the population agrees with the phrase “a good criminal is a dead criminal”.

It’s one of many instances where the dream of reformulating the Brazilian Penal Code clashes with the harsh reality: a legislative project to amend the Brazilian Penal Code was delivered to the President of the Senate in June 2012, and is still being processed. The proposal plans interesting solutions to decriminalise drug use but penalise drug trafficking (mostly inspired by Portugal’s measures) but, in spite of that, foresees that a legal abortion needs a doctor or psychologist to certify that the woman is psychologically unable to be a mother.

It’s impossible to remember City of God without bringing up inclusivity and race: the film trained at least 200 black actors. Most of the cast came from a favela acting workshop called ‘Nós do Morro’, including Seu Jorge (Mané Galinha / Knockout Ned). There were more than 60 main actors, 150 secondary actors and 2,600 extras, most of them children and teenagers. However, many of the actors were not able to find work after the movie came out. “Maybe people couldn’t see the potential that those kids had,” said Jorge in 2013’s documentary City of God – 10 Years Later. Alexandre Rodrigues (Buscapé) last acted in a Brazilian telenovela in 2017, and some newspapers reported him working as an Uber driver. Leandro Firmino (Zé Pequeno), Michel Gomes (Bené), Roberta Rodrigues (Berenice), are still acting, and Jorge went on to act in 25 other movies, including Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.

Had the dream become true, more Brazilians’ stories could have sounded similar to Buscapé: with a legal job and away from crime. But instead, City of God remains current: every time we watch it, we learn new things about the harsh reality of many places in Brazil – but we are also reminded of the beauty of cinema and great storytelling. 20 years later, the movies are still a place where we go to escape reality.