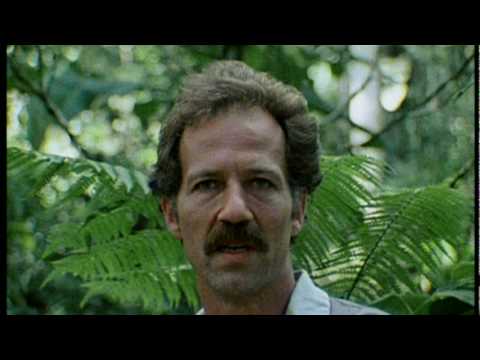

Werner Herzog stands in front of the dense and oppressive green of jungle vegetation. He is lean, with thick head of hair and a moustache. “I see the jungle as being full of obscenity. Nature here is vile and base,” he says, and the camera cuts to footage of a man slicing the wing off a parrot. “I wouldn’t see anything erotical here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and then just rotting away.” It’s curious that this extract from a documentary about the making of Herzog’s best-known film Fitzcarraldo is a more precise insight into his worldview than you might find in any of his 60-odd films. On a personal level, discovering this clip was a revelation – Herzog’s words cut through the disquiet I feel about the vast majority of nature writing, music and art that reduces the world around us to a twee banality. I ended up quoting from it in my book, Out Of The Woods.

Herzog’s radical view of our relationship with the natural world is the recurring subject of his art. It shapes not only his fictional films such as Aguirre, Wrath Of God and Rescue Dawn, but also his documentaries, such La Soufrière, Encounters At The End Of The World and especially Grizzly Man, the portrait of Timothy Treadwell’s delusion that he can form a kindship with, rather than lunch for, giant wild bears. This stark understanding of the human struggling against weather and landscape is the dominant theme of Of Walking In Ice, the short book in which Herzog gives an account of a walk (or pilgrimage) that he made from Munich to Paris in 1974. It is arguably – and Herzog makes the case for this himself – his finest work.

Lotte Eisner was a German Jewish film critic and historian who, in the years after the Second World War, proclaimed Herzog to be one of the filmmakers creating a new German culture after the barbarity of the Third Reich. Learning that she was seriously ill, Herzog decided that if he were able to walk to Paris, Eisner would live. Of Walking In Ice is his lucid, uncanny, dreamlike and occasionally hilarious account of that journey through harsh, frozen landscapes of Europe. Imagine Pieter Bruegel’s masterpiece ‘Hunters In The Snow’ in hyperreal literary form, as vivid and potent dissection of a encounter with the natural world as any moment Herzog’s films. He has himself said that he believes his writing will outlive any of his cinematic work. It’s certainly interesting that it is two filmmakers, Werner Herzog and Derek Jarman, who are the greatest nature writers of modern times. More than the rest of those working in the form, they have managed to combine the wonder and awe at what we see around us with an acknowledging of the powerful forces of sex and death that shape it all. Their cinematic eye translates this in a literary imagery that is luminous, almost psychedelic at times.

As Herzog approaches his 80th year, he shows no sign of letting up. His new film Family Romance LLC is a curious work. Shot by Herzog alone on video in Japan, it’s a fiction-not-fiction about an agency that provides a stand-in family members, colleagues and employees for difficult situations. Even in this exploration of the modern human, there’s an extended scene in which the fake father, and agency director, takes selfies with the ‘daughter’ he’s been employed to lie to among the cherry blossom of the Japanese springtime. With Werner Herzog, fetishised nature is never far away.

The Guardian recently ran an article that asked if Werner Herzog’s ‘brand’ is overshadowing his work. What with his starring role in The Mandalorian he’s increasingly becoming a household name, not to mention the way in which his accent and appearance has almost become a meme. Yet when you’re someone with as singular a vision of Herzog, trying to navigate the strange waters of financing his filmmaking must be a nightmare – better to become a brand, perhaps, than be forced to compromise by working with them. In any case, perhaps the Herzog ‘brand’ is the whole point, an approach that his life is his work, and vice versa. It certainly fits with the feeling one frequently gets when watching many of his films or reading Of Walking In Ice, Conquest Of The Useless or magnificent interviews collection A Guide For The Perplexed: whether through his lens or pen, in Werner Herzog’s art fact and fiction are less significant than his enduring pursuit of what he calls "the ecstatic truth". It’s hardly surprising that his own identity has been subsumed into the quest.

Werner Herzog’s Skype icon is a sepia photograph of a rocky island, silhouetted against the glare of a bright but turbulent sea and a sky ragged with seagulls and the remnants of a storm. As the ring tone bing-bongs, the image dissolves into the instantly-recognisable face of the film director, calling from his study, businesslike and headphones on, entirely unphased that we’re not here to discuss Family Romance LLC but instead his deep dives into the essential and eternal human dialogue with nature that is at the core of his writing and filmmaking, his "burden of dreams". This is what has driven Werner Herzog’s life since he was born in Munich on 5th September 1942, just as the RAF’s Bomber Command began to intensify its bombing of Germany’s cities:

Werner Herzog: I was in my cradle under a layer a foot thick of glass shards and brick and debris, but I was completely unhurt. Of course for a mother it was not a good experience and she fled to Sachrang [a remote village in the south of Germany]. It became my home and my language, because I spoke Bavarian with a very heavy accent.

In your 1986 film Selbsportrait you discuss the forested landscape around Sachrang and how you used to play within it, I wanted to ask about the impact it had on your imagination?

WH: It was not only the forest, we lived in a tiny house next to a farmhouse, there were meadows and in winter there was very good skiing, and a creek behind the house that ended up in a secret ravine and a waterfall there. So it’s very mysterious landscape for us as children, not just a landscape but a mythical place inhabited by mythical people.

Who were they?

WH: For example a strongman, a young lumberman, who did wild things, poaching, fleeing the police and smuggling across the Austrian border which was just a mile away. He looked like what today we would call a bodybuilder, an absolute muscleman. The milk truck broke through the bridge of the creek. I don’t know how many tonnes it was, 15 or 30 tonnes, and they called for the young man, the strong man. In front of everyone he takes off his shirt and wades down into the water and makes an attempt to lift the truck out of the creek. His muscles were bulging but he couldn’t move it a millimetre and of course everyone knew it, but to see him display that he would tackle the task to hoist it out single-handedly was a wonderful, almost mythical experience for us.

How old were you when you saw that?

WH: Five or six or so.

Did it have a profound impact on you?

WH: Not a profound impact no, but it was a landscape full of fairies and it was inhabited for farmers and lumbermen who had a quasi-mythical status.

Did this extend to an awareness of the German cultural relationship with forests, or had that thread been interrupted by the war?

WH: Germany is not the only country with a culture that is focussed on forests. Of course it became notorious because the Nazis made some sort of a cult out of the German forest. But I was not aware because the forest and mountains around the village was the natural habitat, there was nothing special. We needed the forest because we had no firewood, we had to go and collect twigs and branches.

The 17th century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico wrote The New Science, a sprawling work that unites all the human stories and myths in an evolution narrative that emerges through our relationship with the forest. In Of Walking In Ice you wrote "truth itself wanders through the forest". I wonder how these ideas of myths and forest, or jungle, connects to your filmmaking and writing?

WH: We should be careful about the myth of the forest because when you quote the sentence "truth travels on foot through the forest" [sic], for me the centre is travelling on foot. The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot. I am not going to explain it any further because nobody is travelling on foot anymore, so I can say it only as a dictum. The forest reveals its truth for those who are travelling through it on foot. We shouldn’t dwell on it, because we are on the internet and whoever sees this is going to be on the internet and nobody will travel on foot a thousand miles. I am a lazy bum as well like everyone else, but I do travel on foot when there is something of existential importance. Then I will do it on foot.

Now living in Los Angeles, a city built for the motor car, and being somewhat older than you were when you walked for Lotte Eisner, what’s your relationship to walking now? Do you still walk and could you still walk for an existential purpose?

WH: Not in Los Angeles, it is not a place made for walking and you are speaking of ambling along the streets of a city. If somebody in Guatemala City was of existential importance for me and I had to see him or her I would travel irrespective of the distance, 2000 miles I would do it. I think I would still do it.

You’ve said previously that we have an "inadequacy of imagery" in modern culture and I wonder if that can also be applied to how we see the natural world through the eyes of the Romantics, especially in Britain, where we have an ossified view of how to approach nature. How do you relate to Romanticism and landscape?

WH: It is foreign to me. It is strange because sometimes those who do not know how to deal with my imagery, with my films, just out of being insecure say ‘he must be a romantic’. Just read what I am saying about mother nature. Just listen. I rant against the jungle. You will immediately understand that I am not a romantic. There is something deeper than the British or German romanticism. I make a point when I did the film Cave Of Forgotten Dreams, I am filming in Southern France in this gorge and all of a sudden there is a natural arch, a monumental, incredible – I say it with necessary caution, in quotes – ‘romantic’ quality to it. My feeling is that prehistoric man 35,000 years ago venerated this place with a notion of seeing a very specific landscape that carried elements in it that appeal, that resonate in our soul. So romantic landscapes do not belong to the Romantics alone, they belong to Crog-Magnon man and they belong for example to St Francis Of Assisi. When you go to his monastic settlement in the Apennine Mountains it’s exactly this kind of romantic, but it was centuries before the Romantics showed up.

In terms of dispelling Romanticism I found the passage from Burden Of Dreams in which you discuss the jungle inspiring as you hit on a truth, that the chaos and “overwhelming fornication and murder” of the jungle can apply to any forest, or wild place, that you are in.

WH: Yes, and I see it the same way. You can read a lot about my relationship towards nature, or wild nature, when you read Conquest Of The Useless. It is a such stark, naked assessment of nature, or when you hear me commenting in a film like Grizzly Man, it’s a stark naked, anti-romanticising attitude. Romanticism of course has evolved into a very low-class, Disneyisation, a cheap Romanisation of wild nature where the bears are all fluffy creatures that you have to hug and you have to sing songs to them.

In my experience of nature art and writing we’re often looking at the natural world, we don’t see ourselves as part of it, whereas in your films and writing that’s the central question – you’re exploring humans as part of these fundamental places like the jungle. Watching that scene from Burden Of Dreams around the time I read JA Baker’s The Peregrine was very helpful in unravelling the assumptions that we have as a culture about this relationship with nature, it’s beyond what we normally see as ‘nature writing’

WH: The Peregrine is a form of ecstatic truth, of extasis, which in Greek means ‘out of your existence, you step beyond the boundaries of humanness’. And of course The Peregrine is written in prose that we have not seen since Joseph Conrad, such calibre. I would defend JA Baker against those narrow assessments of his writing.

You’ve said you feel your writing will outlast your films – have you thought you would like to write more?

WH: Now since there is a lockdown and I can’t move out with my camera, I am writing, I am writing poetry and prose texts, I am full of it now, at the moment. [Herzog beams and shuffles papers on his desk]. It’s funny because my publishing house in Munich have for years become threatening, telling me ‘you must write more, that’s what will remain, that’s what you have to do’. I sent them a few samples of what I just wrote yesterday and the day before yesterday and they are going completely bonkers over it. So there will be some good stuff coming.

I want to return to Lotte Eisner, the reason for your walk from Munich to Paris and Of Walking In Ice, and what she said about you being part of a new generation of filmmakers rebuilding a German culture after the barbarity of the Third Reich. I’ve always felt as if the musicians who were your contemporaries, such as Harmonia, Cluster, Can, Neu!, were doing a similar thing with music as you did with films, and sometimes embracing a real vision of a German landscape there too. Do you feel a kinship with those artists in some way?

WH: They are unknown to me. I’ve never heard any of those names.

But you worked with Popol Vuh on your soundtracks, do you feel they were creating a new German musical culture?

WH: Not really no. I started to drift apart from them, well actually one person, Florian Fricke, who essentially was Popol Vuh, because he drifted into quasi-philosophical nature feeling New Age babble, which is an abomination for me. In his later days he didn’t represent anything but a stupid, pseudo-philosophy translated into music.

Again that’s exactly what happens with so many people trying to make art and writing related to nature, it becomes a new age babble, simplistic and transactional

WH: It ends up with smiling monks singing choirs for giving you the feel-good over the internet. It makes me cringe.

Quite right. Again thinking back to that post-war period, I wanted to ask about heroism, which is such a strange concept. In your films people have these beautiful yet impossible dreams that they’re trying to fulfil, which is different from heroism, and I wonder if that comes from growing up in a time when there were no heroes in Germany. In Britain were forced to believe in heroism due to the wars, and maybe in Germany there is an inverse. Does your interest in these people with fantastic dreams come because of that?

WH: It doesn’t constitute heroism, it just describes a dreamer. I do have a clear attitude towards heroism and it has become more solid through Dieter Dengler, with whom I did Little Dieter Needs To Fly. He was always considered a war hero, he was the one American who in captivity in North Vietnam managed to escape, and through an ordeal that was unspeakable. He was considered a hero and he said ‘no no I am not a hero I am just a courageous man’. Heroes are only those who are dead, who have died for their country and in defence of their country. Those are the heroes, and that’s the exact definition for me. There are no sports heroes, there are no whatever other heroes, I am very cautious of the term.

Many of these key characters with powerful dreams or quests in your films are men. Is there something about masculinity that you find interesting that you’re exploring in these films?

WH: No, I also describe a female, almost heroism, when you look at Land Of Silence & Darkness the woman protagonist is deaf and blind at the same time, and she is soldiering on, she is a very good soldier. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with masculinity.

From the chaos of nature I wanted to ask about your interest in mathematical theory and chaos within that – I understand you’re interested in in Riemman’s Hypothesis and have had to ask a mathematician friend about it as I failed to grasp it in two days… When did your interest in mathematics begin?

WH: It has always been there since very early on, I could have become a mathematician, for example. I can still feel the itch of it, but you have to be into it when you are very, very young. All the great mathematical breakthroughs, the real big ones, have been made by young kids, between 14 and 24, so I am way too late. But I feel the itch and I am fascinated by number theories and Riemann. But I could have been an archaeologist, I could have been an athlete, I wanted to be world champion of ski jumping as a kid – The Great Esctasy of the Wood Carver Steiner is my real alter ego, doing what I dreamt of, flying. I am sorry to have brought you into such obscure things as Riemann’s Hypothesis.

It’s fine as my mathematician friend is really interested in these things, and she wanted to know how mathematics and ideas of order and chaos in nature fit into your worldview, and should we strive to know the unknowable and find order in the chaos?

WH: The distribution of prime numbers is not going to give us a harmonious balance within numbers, that’s not going to happen. We know that because we know billions of prime numbers already, and there is no apparent pattern or what might be harmony. What is fascinating with mathematics is that almost everything that has been done in mathematics is rooted and based in the very deepest of all natures of numbers, and that is in prime numbers. In the two-and-a-half-thousand years since Euclid there have been attempts to find out, and Riemann and others were the ones who started to articulate a pattern that seems to be right. And if Riemann is not right with his hypothesis it would have catastrophic consequences in the validity of many, many mathematical constructs. Much will collapse.

[The telephone rings]

I think it is the next interview, may I distract them. Yes hello? Can you call in ten minutes. Ah. You are going live… the BBC. We will do it in a few minutes.

[The sound of a producer speaking frantically. Werner Herzog hangs up the telephone]

I don’t want to run over the BBC so finally, in Selbsportrait you mention returning to that landscape you grew up in, and I was wondering what it means to you now?

WH: Whenever I’m in Munich I would also travel to Sachrang. It’s sobering and disappointing, that is the overwhelming notion. It has changed so much, there is such a distance between my childhood Sachrang and Sachrang today, but that is how history is functioning. I don’t feel a sense of loss. Sachrang is still there and it will live beyond me and that’s fine.

Family Romance, LLC is available on Curzon Home Cinema, BFI Player, MUBI, Showcase and as virtual screenings through local cinemas on Modernfilms.com. Listen to Luke Turner discussing Herzog’s Of Walking In Ice on the Backlisted podcast here