THERE IS THAT

On the ninth day, reality sinks in. Like most people, I’ve filled the endless hours at home with music, TV, and of course books and magazines, but never without music. Never, ever without music. For starters, I have records to review, and there are always more to check out. And then there’s the stillness outside. Once, it was fascinating, but now it’s almost unbearable.

These days, the cobbled streets beyond my apartment rarely rumble with trucks, nor are bones rattled by bikes. At nights, the pavements where hipsters searched loudly for the bar where “you have to ring the bell, and there’s no sign” are uninhabited. The playground behind my bedroom, from where children used to wake me early on hungover mornings, are deserted. There’s no singing in the community centre, no bass from parked cars, and I can’t even remember the last time I heard a plane overhead. Berlin is practically dead.

A few days ago, on a rainy afternoon, I cycled, for the exercise, across the city in which I’ve lived for nearly fifteen years, seeing it as never before. No one wandered through Brandenburg Gate. Alexanderplatz, East Berlin’s Trafalgar Square, held one single police van, itself vacant, and not a single other soul. Beneath a grey sky, the damp monoliths populating the Holocaust Memorial glistened like dark, marble coffins piled up on a hillside. I’ve always wondered what it would look like here without tourists. I never anticipated seeing it without its citizens. Berlin, like most sensible cities, is in hibernation, just as spring arrives. It’s like its heart has stopped beating altogether.

THAT IS THAT

On the ninth day, I wake late, having texted with my girlfriend into the small hours. We last saw each other almost two weeks ago, when – having spent three weeks together, the most since the start of our relationship – I’d held her to me in the desolate, concrete-vaulted shadows of Manchester Airport’s short-term car park, watched over by two police officers occupying the only other vehicle in sight. We’d spent the preceding days agonising over whether it would be better for me to stay – I could offer support to her and her two children through the days and weeks ahead – or whether her cosy flat simply didn’t offer enough room for the four of us. Last night, on the phone, I’d become sentimental, and the manner in which I’d confessed feelings that I’d never done face to face had overwhelmed her. She was quiet a while, and I couldn’t read her eventual response. She reassured me she was still merely stunned, but I worried I had inadvertently upset her, perhaps because I’d waited till I was protected by a screen, marooned in a foreign city 600 miles away, almost entirely inaccessible, to reveal such things. I wished I was on the sofa with the tattered tassels and punctured wickerwork. Though separation is part of our routine, we’d both known our farewell was ominous.

Inside the airport, some of what looked like the last flights out of the city were preparing to depart. It was a Friday, but the mood was sombre: easyJet’s computer systems were down, and staff were valiantly trying to tag baggage manually or provide handwritten boarding passes for those who couldn’t access the app. Others did their best to explain calmly to emotional passengers that they wouldn’t be allowed ‘home’ because they didn’t have the right paperwork. Beyond the security gate, shops were almost empty, if they were open at all. Strolling through Duty Free, its garish colours, multiplied by mirrors unimpeded by customers, seemed psychedelic. I’m not sure anyone left was sure we’d leave at all. I asked a Boots employee, as I bought the last packet of Aspirin, how her week had been. “Weird,” she replied. “This was my first week in the job.” I feared it might be her last.

On the plane, three men, red-faced and sweating, planted themselves nearby, one choosing a seat across the aisle, another to my front, the last to my rear. I couldn’t tell if they were hungover, drunk, or sick. I pulled my scarf up over my mouth and nose, wishing I’d been able to find a mask these past days. Then, slipping my headphones on, I played a song I first shared with my girlfriend fourteen years ago, back when we first met and she was seeing someone else. She’d never heard it before, but these days loves it as much as I do. I couldn’t listen for long though. Having lived with it over half my life, I didn’t want to associate it with this journey. Instead, I stared out of the window. I scrolled through the headlines. I ate the sandwiches I’d bought at WH Smiths, where the shelves had been almost bare. Finally, though it felt like an extravagant gesture, I walked to the back of the plane, glancing at others who, like me, felt they were leaving Pompei, only to fly to Pompei. As I thanked the steward and stewardesses for getting us home safely, they looked like I was the first person to say anything kind to them all week.

STAY HOME. STAY TOGETHER

On the ninth day, I get up late and prepare some tea, before heading back to bed to read the news. “Just 2,000 of half a million frontline NHS staff have been tested to date for Covid-19.” “It has emerged that a major NHS hospital in London almost ran out of oxygen for its Covid-19 patients on ventilators last week.” “Trump has admitted the federal US government’s own emergency stockpile of protective equipment is nearly exhausted.” “In the next few days we will reach one million confirmed cases and 50,000 deaths.”

I make more tea. There are records to review, and always more to check out. There’s never time for silence. I need to write about Whitney Houston’s debut: 425 words on an album I’ve never cared for at all. Honestly, what’s the point? As ‘You Give Good Love’ starts, I head for the bathroom, barely aware of the music at all. I take a mental note that I need more toothpaste, wash my hair, and shower efficiently. By the time I’m dressed, ‘Saving All My Love For You’ has started. “You’ve got your family,” Houston sings, “and they need you there.” It sounds somehow different today.

I think again about my girlfriend, and of her kids. Then, curious, I look up the lyrics online. I never realised the song was about a woman in love with a married man who keeps her dangling with the promise of love to come. It sounds really different today. And my God! Whitney could sing! I pen an apology as a review. Not, for once, an apology of a review. All that time I spent deriding her, and what do I have to show for it? How about a little compassion?

THIS IS HIS

On the ninth day, I skip breakfast for lunch. Normally I’d have seen Judith from the Britpop-themed bar across the road – try as hard as you might, your baggage always catches up with you – taking her dachshunds for a walk. Not today. Normally the chef downstairs would have disturbed me with his food mixer, or the smell of something unidentifiable yet familiar would waft into my hallway. Not today. Normally I’d have heard the post woman park her bicycle, the front door creaking, perhaps the doorbell as she leaves another package. Not today. Today, though, is the new normal.

I warm up soup for the third lunch running. I check my bank account, then donate to a worthy cause. Petitions and fundraisers arrive so often these days it’s hard to know which to choose, but my subsidy from Berlin’s government for lost income arrived yesterday. I only applied on Sunday night. I feel uncomfortably grateful that Brexit forced me to apply for German citizenship earlier than I’d intended. I’m way more grateful Germany accepted me.

I’m terrified by what’s happening at home. In Britain, I mean: I don’t know where home is anymore. Britain’s where my heart lies, at least instinctively, and Germany’s where my heart lies, if rationally. Perhaps I’m a “citizen of nowhere” after all. It felt unreasonable when Theresa May said it. Back then, when we had planes, my mother and sister lived little more than five hours away, door to door. Home was here, home was there. The world was our oyster.

THIS IS HERS

On the ninth day, my girlfriend sends me a photograph, taken in woodland near Leeds. It shows her youngest daughter joyful on a rope swing, her blonde hair tousled, illuminated by spring sunshine. Over New Year, the first time I met her, I’d spent a week living with her, her sister, and their mother, and we’d driven to a farm on the Yorkshire Dales, where we’d played in barns full of straw and excitable screams, then eaten burgers and drunk milkshakes in an American retro-style diner, my heart brimming with life’s pleasures.

Only three months ago, as I held her by the waist, this little girl had stood on hay bales in front of me, gripping a rope, white-knuckled and paralysed with fear. Before her last attempt to launch herself into space, she asked me to film her, then jumped. As she swung back across, like a pendulum, she yelled my name, and before I could put my phone away she burst into tears, terrified I’d abandoned her. Today, it appears, she’s mastered the art. Today, she doesn’t need me at all. I’ve missed out on an occasion. During my visit at the turn of the year, she drew me a card. One corner was folded over, labelled with an instruction to read beneath. “I think you love Mummy,” she’d written. I hope she hasn’t forgotten.

I settle down on my sofa to review another album, flipping between the notes I’m making, the accompanying press bio, and lyrics. It’s Paul Weller’s new collection, and it’s good, the sound of a man at peace: “I looked in my heart/ And saw myself for what I am/ Found a whole world in my hand.” If only it were that easy. It’s been nine days of isolation now, nine days in which the only face-to-face conversations I’ve had for more than a minute have been with a neighbour surveying depleted grocery shelves with me the morning after my return, and a musician living nearby who spoke with me from the pavement as I relished my first-floor balcony. Otherwise, it’s been all Facetime and WhatsApp. That isn’t the “world in my hand” I need. I’m used to working alone each day, but usually there are signs of life.

© Wyndham Wallace

AND THIS IS OURS

On the ninth day, I make myself two strong coffees, twice as much as I’d normally drink. Soon, I find myself restless. I went running yesterday, but my muscles are still stiff, and I’ve reached the age where my poor knees can’t take the punishment. I could go for a bike ride, but it’s drizzling. Maybe I could try some sit-ups, but I should probably let my food digest. I’m not sure I want to go out anyway. I feel self-conscious wearing one of the masks I found online, but, in recent days, after my initial complacency that people of my generation will be fine, I’ve become a little more nervous. They’ve just announced that Adam Schlesinger, from Fountains Of Wayne died last night from the virus. He was only four years older than me. Last week, I felt pretty fit for a 48-year-old. Now I feel vulnerable. Context is king.

These days, every song reads differently, whether I know its lyrics or not. Father John Misty’s “Now I mostly spend the long days walking through the city/ Empty as a tomb”; The Psychedelic Furs’ “Don’t be surprised/ When these houses all fall to dust”; Elbow’s “There’s a hole in my neighbourhood/ Down which of late/ I cannot help but fall”; The Blue Nile’s “In love we’re all the same/ We’re walking down an empty street”. I still can’t listen to that one. It’s the track I gave my girlfriend back in 2006. We put it on in the car only three weeks ago. She started crying: it had been playing as she gave birth to her first daughter. I’d never known that before.

It’s funny how music adapts to our situation. It accumulates weight, hoarding experiences only evident in a certain light. ‘The Downtown Lights’ is Oxford Street’s HMV during lunch hour from my first post-school job. It’s my last night at university, lost on Dartmoor in the mist. It’s driving home from Basingstoke – yes, Basingstoke – to my parents’ house one sunny afternoon. It’s the Nuremberg second-hand store where I finally stumbled on a vinyl copy last summer. Now it’s her song. Now it’s our song. And it’s your song, too, if you want it. Since nothing seems the same, maybe it will speak to you more. If I’m honest, though, right now nothing’s connecting. We’re still bedding in. This won’t last forever, but it feels like it could.

LET US JUST DO IT. LET US MAKE MASK AND HELP ONE ANOTHER

On the ninth day, I finish my last review before preparing dinner, the same vegetable stew I’ve eaten since Monday. My girlfriend’s emailed me the skeleton of a new song, and after listening to it I joke that it’s strange how someone whose music can be so dark makes me so happy. “I have touched the underbelly of existence,” she writes back, “and I feel very proud to have done so, hopefully so others don’t have to. And I am a stupid slapstick northerner who loves to take the piss out of herself too. Great combo.” I miss her laugh. I wish we could share this stew. As much as anything, I’m tired of it.

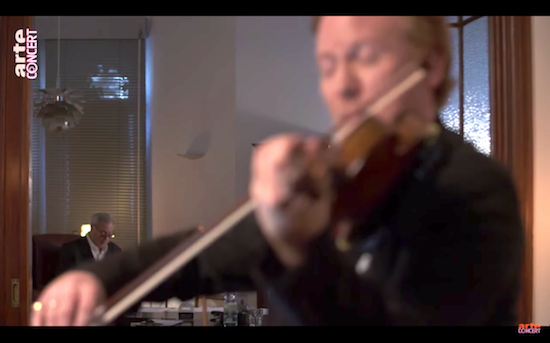

Someone’s posted on Twitter about Daniel Hope, a world-class violinist I met a few years back when, in the days one still could, in Berlin’s biggest convention centre – alongside, surreally, Enigma’s Michael Cretu – I interviewed him on stage (or, to be precise, seated on tall stools in a roped off section of a busy corridor). We’ve stayed in touch intermittently, and I particularly love his recording of Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi – The Four Seasons. I switch on Hope@Home, which he’s been broadcasting every night from his apartment for TV channel ARTE, performing with pianist Christoph Israel. I can’t listen today to any more guitars or synths or drums, or even anyone singing. I’m not ready for Netflix either. But I’m still not prepared for the stillness.

Tonight, Hope is joined, from an adjacent yet distant room, by theatre director and playwright Robert Wilson. A collaborator with Philip Glass on Einstein On The Beach – among many fine achievements – he’s been unable to return home to America since lockdown. Hope explains how, having worked with Wilson previously, and having learned he was stranded in Berlin, he invited him to take part. Perhaps Wilson could choose something suitable to recite while he plays? Wilson, though, has written something especially, for which, Hope confesses, he’s struggled to find the right accompaniment. In the end, he’s picked a piece I know well: Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel Im Spiegel. I first heard it in the days following my business partner’s suicide. Hope dedicates it to Ellis Marsalis, Jr, who died last night of the virus. In time, they’ll say he was old; it would have happened soon enough anyway.

ODDLY, BEING APART BRINGS US CLOSER

On the ninth day, reality sinks in. There’s stillness everywhere. On the streets, through my apartment, inside me. Hope’s violin sings. Israel teases out Pärt’s delicate arpeggio. Their notes sound like tears. And then Wilson starts to speak, tentatively, desperately, trying to communicate something impossible, as if emerging from water. “There… is… that,” he says. “That… is… that.” I’m reminded of the early scenes in The Possibilities Are Endless, a wonderful, touching documentary about Edwyn Collins’ recovery from a stroke. “There is that,” he falters, his voice croaking. “That is… that. There are, there is.” He seems a little confused now. For a moment, in fact, this whole endeavour seems faintly ridiculous, even pretentious, almost certainly a waste of my time. “Is that is?” he continues, his voice, slowly yet surely, beginning to take on a soothing, noble character. He reminds me of someone I once knew, someone no longer with us, someone I once really cared for, someone who cared for me. “That is that. And that! It is.” His hands, no doubt chafed from washing, tremble as he grasps for meaning. Everything is familiar, but nothing makes sense. I don’t know what to do, so I cry.

“This is hers,” Wilson proclaims, his voice suddenly filled with wonder. “This is his,” he adds, his voice rising. “And this is ours.” It’s a proper cry, a shuddering, gasping, I-don’t-want-this-to-end cry. “And that is what it is.” I’m not really so sad. “And so be it.” I feel almost unburdened. “Stay home. Stay together.” I might even say I’m happy. “Reassess the silence.” Music accumulates weight. “Families take care of each other.” His voice splinters. “Stay home. Stay together.” We’ve never felt lonelier than this. Then, “There, there, there, there,” he intones, to calm us. “There! There! There! There!” he reiterates, as if pointing out the stars. “This is a time to help one another. Exactly. And Exactly.” I haven’t heard such optimism in weeks. “What seemed impossible is now inevitable… Our world will be different… Together… Apart… Brings us closer… Stay home… Oddly, being apart brings us closer.”

At first, I think he’s said something else: “Hardly being apart…” I might have actually preferred it. Ultimately, that’s all we are: hardly apart at all. Either way, he’s right. He sounded right, in any case. He must be right, right? Slumped behind glass, he lays down his papers, then clears his sinuses loudly. He’s forgotten he’s not alone. He looks like he’s been weeping. Sighing, the music dies, and in the emptiness that follows Wilson utters his last words too. “Lights,” it sounds like, which would have been perfect, but later I’ll learn his microphone was switched on a little too late. We were meant to share a line from Shakespeare: “And the rest is silence.” Even now, we fail to communicate.

REASSESS THE SILENCE

Tomorrow will be the tenth day. Reality has sunk in. Never without music, though. Never, ever without music. This way, the stillness isn’t so unbearable.

THANK YOU TO ALL WHO MAKE MUSIC, HAVE MADE MUSIC, AND WILL CONTINUE TO MAKE MUSIC