In 1987, David Bowie was feeling relaxed. In later years, he’d claim maybe less so, but doing the rounds of interviews to promote Never Let Me Down was old hat in terms of procedure, and so sitting down with Scott Isler for a feature that would be the cover story of a major US music monthly publication, Musician, went conversationally, giving enough away and helping prep the way for the Glass Spider tour as well.

By then, of course, he’d seen a few things, heard a few things, took them in and synthesised them and brought them back with the help of others and could, from the perspective of the ripe old age of 40, indulge in some veteran thoughts. His own near-complete reintroduction of his past to everyone else was two years off with the Sound And Vision box set and the subsequent series of reissues, though the very earliest work was not under his control, to his frustration. So the separate reissues about to emerge didn’t immediately include the clutch of songs from when he’d ended up for a shadowy stint with a bunch of fellow Londoners, the Riot Squad, for a couple of months in 1967.

Some weeks before then, he’d heard this amazing new band out of New York that nobody else in the UK knew about, thanks to his manager Ken Pitt ending up over there for a meeting with Andy Warhol. Pitt brought an acetate of the band’s forthcoming debut back to the UK, gave it to Bowie, and the latter freaked out. He said he started covering one song ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ almost immediately, well before the formal release of The Velvet Underground & Nico, and eventually pressed the Riot Squad into indulging him via a recorded version. He also wrote and sang a new song, ‘Little Toy Soldier’, which was essentially another track from that album, ‘Venus In Furs’, with some different words. Neither of them sounded anything like the actual band, however much Bowie wanted to try and match its lead singer, but still, you’re young, you’re trying, you aim for your own thing.

So perhaps in 1987 Bowie was thinking about his half-as-old self who had had the earnest naivete to try and translate a new ‘greatest band ever’, a general effort he worked on perfecting over decades. But if he was thinking about that past, he wasn’t going to fully let on. He did have some words, though, for two people who had loved The Velvet Underground in the interim. These two people had the relative misfortune to be nine and six, respectively, in 1967, to have not been David Bowie and to have not gained the regular acquaintance of Lou Reed in later years. So when asked what music he’d been enjoying lately, Bowie immediately enthused about the Screaming Blue Messiahs – “the best band I’ve heard out of England in a long time” – and then without missing a beat went: “I tried the Jesus and Mary Chain but I just couldn’t believe it. [laughs]; it’s awful! It was so sophomoric – like the Velvets without Lou. I just know that they’re kids from Croydon [laughs]; I just can’t buy it.”

And that was that, moving on to dismissing recent work by The Fall and celebrating The Beastie Boys before turning back to his new album.

Jim and William Reid are not, indeed, from Croydon. Neither is Douglas Hart, nor Bobby Gillespie. A few other key people in 1985 weren’t either. Alan McGee? Nope. Geoff Travis? Indeed no. John Loder, the engineer for the album following a good experience with a single, was from the Plymouth area. Anyway, Bowie was from Brixton. Maybe he just had a bitter rivalry with Croydon in his head. As it happened, Loder’s studio Southern, belying the name, was in Wood Green in north London.

In the book he and his brother released the other year, Never Understood, William Reid makes it clear at one point that while he did love rock biographies when younger, when he read the late David Cavanagh’s history of Creation Records he got frustrated with the smoothing out or reductiveness of histories like it, for all its exhaustiveness, and apparently has never read another one. Understandable, given that more than once both Reids talk about looking back across four decades and feeling something of a weight of history. In the end, Jim talks about the recording of their debut the most in the book.

There are now various accounts of everything that happened around then and unsurprisingly there’s some differences of opinion and detail. Jim Reid and Hart talked about it in 2011 for the Quietus. Gillespie’s accounting of the time he was in the band via his memoir Tenement Kid is much more detailed than the Reids’ own book is in covering the same period. William Reid’s opinion on Cavanagh has been noted. At one point McGee called Cavanagh’s book ‘the accountant’s version.’ The Reids forcefully disagree with McGee’s account of a key meeting with Travis that would determine what label would end up releasing the debut Jesus and Mary Chain album. There’s also Wikipedia and honestly if you just want a quick overview of things you can read that but if you ask any of the people I’ve already named they’d probably all find things wrong with it in turn.

Mythology relies upon location. Timing, luck, accidents of history, you absolutely need all those as well. The Reids are straightforward enough on these fronts, with, for example, William speaking in their book about their dad getting laid off due to the workings of international capitalism meant redundancy which meant money to get a Portastudio, without which the album wouldn’t have been made. But above all else it really seems to be about location for the Reids, for East Kilbride being exactly what it was so they had to leave. I couldn’t tell you anything about East Kilbride; most anyone who has learned about it because of the Jesus and Mary Chain knows little about it either.

The Reids spent most of their childhood into their early 20s there. They knew they had to leave long before they were able to. They have been clear in their praise of what they found good enough, or even helpful about the area, like its library, but otherwise describe a sociopsychic air of acceptance of the mediocre and destructive. They felt their lives after school were being mapped out for them as much by lack of opportunity as by failure of their school to engage them. There were failed attempts to work in local factories. A tape of their music was passed to Bobby Gillespie before he joined the group, he passed it in turn to Alan McGee. The band went to London to play their actual first show, and it began.

It only occurred to me when reading Never Understood that there’s something weirdly fascinating about it. There’s a chapter named after the debut album, the only one of the Jesus and Mary Chain’s releases to be so marked in the book. As noted, it’s mostly Jim with occasional comments from William. John Loder is praised highly for his informative but generally hands-off engineering, letting them get on with it. There are tales of upsetting the members of Crass via the Reids and crew preparing bacon butties, Ministry were doing work as well in their Twitch-era days. At one point William accidentally wrenches off a studio door and guesses that Loder billed Warner for it.

They don’t talk about the actual album, though.

The recording of it, yes, but not the album’s contents. ‘Never Understand’ gets mentioned because it was the second single they released and their first experience with Loder at his studio. A couple of songs get mentioned around then as well, like talking about playing ‘You Trip Me Up’ to some bemused b-boys at Danceteria in New York City. But you’re not going to get anything close to a detailed “here was what we recorded on this album and what the songs in specific were and the lyrical inspirations and a particular anecdote about this particular song” telling. A later b-side gets the most detail in the end and that’s because they recorded some falling rain during those sessions that was used as an overdub.

This could be seen as unfortunate, but later William makes his case in the book directly: “A song is not just a set of instructions. Isn’t a song something that just vibrates and anyone can look into it and get what energy they want?” That’s a big reason why I love the “my rubber holy baked bean tin” line because when I first heard about it I went “Whuh?” and then I finally heard it and then listened to it again and thought, “It’s kinda Marc Bolan, so why not?” (It helped I was starting to get into the Bopping Elf around then, and I wasn’t surprised to learn that the Reids were fans growing up.)

It’s almost protean, those lyrics on the album, and that’s why they work. There’s probably an academic paper or two out there by someone claiming that most of the lyrics are signifiers of coolness more than anything else, trying to define coolness along the way. I’ll take my take on the vibrations, whatever causes them: motorbikes, beehives, honey bees, seeds, knock me on my back, send a heart attack, knife to my head, somewhere I can’t be found, my little undergrou-ou-ou-ound, all sung with that understated though yearning diffidence and breathy murmur in a way that, yeah, aims for cool, and yeah, heard cool before, you know it when you hear it, but was it quite heard this exact way before, two terminally shy and wary brothers comfortable with their circle but on guard with almost everyone else?

“The sun comes up, another day begins, and I don’t even worry about the state I’m in,” good lord, how perfect, and that and all the other lines delivered as hook after hook after hook after hook, hooks pouring out of the speakers, the hooks work, the lyrics work, that’s why this works.

Plus the other thing, feedback.

So besides the Portastudio early on William bought a Gretsch from a friend who sold it behind his dad’s back for £20 and then a Shin-ei fuzz pedal for a tenner from another friend and here we all are still talking about this debut album 40 years later.

The whole point about noise and hooks being an amazing combination is that it already happened. And more importantly, keeps happening again and again. It also works! It absolutely works! It already happened and it happened in a different enough way in this instance that plenty of people were not entirely thrilled, including at the band’s label. But it was a world where Link Wray and Bo Diddley made it happen, where The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix made it happen, where The Sweet and Slade made it happen, where T. Rex and P-Funk made it happen, where The Ramones and The Cramps made it happen, it happened, it happened before and it happened again afterwards many more times. That’s the point! It works! The Velvet Underground had hooks too! That’s the point!

I like the photos in their book of both William and Jim practicing on acoustic guitar in 1979, aiming to get things just so, learning with experience. I like the photo of William bent over a Beatles songbook laid out flat on a table, presumably checking notations or otherwise getting something clear, guitar in hand. I like how they are keen they are in the book to demolish or undercut various myths and assumptions, whatever the motivations, about riots and incorrect ages and more besides, and one of them is implicitly the idea that all they did was find feedback, hit ‘record’ and walked away. I love that they loved Can and Einstürzende Neubauten, and it makes sense how clear it is that their bête noire around then was Spandau Ballet.

In that their own preferred line of musical descent was, dare I say, generally more rockist rather than poptimist (cue endless screaming debates I am not interested in), at the same time they pretty clearly loved the sweet stuff and not just the sour, the winsome and beautiful, not just the Jesus fuck of it all. The album starts with That Ronettes Drumbeat, which always works, which Brian Wilson also knew. It generates a reductive question: “Isn’t this just these two bands smushed together?” But it’s not because it’s a whole stew of things rendered into this thing instead. Well before streaming and the here-it-all-isness of the current time, they picked up on things as they went, built up their collection, listened to things, wrote their songs, recorded them.

So many bands I’ve seen over the years clearly have this album in their collection. So many that I’ve seen absolutely practiced these songs or that delivery or looked for that volume. So many references to the distillation of all the visuals and sonics and posing and sunglasses and hair and whatever else one can imagine. It’s almost a literal feedback loop now, where it seems like when the album ends and you might as well start it again.

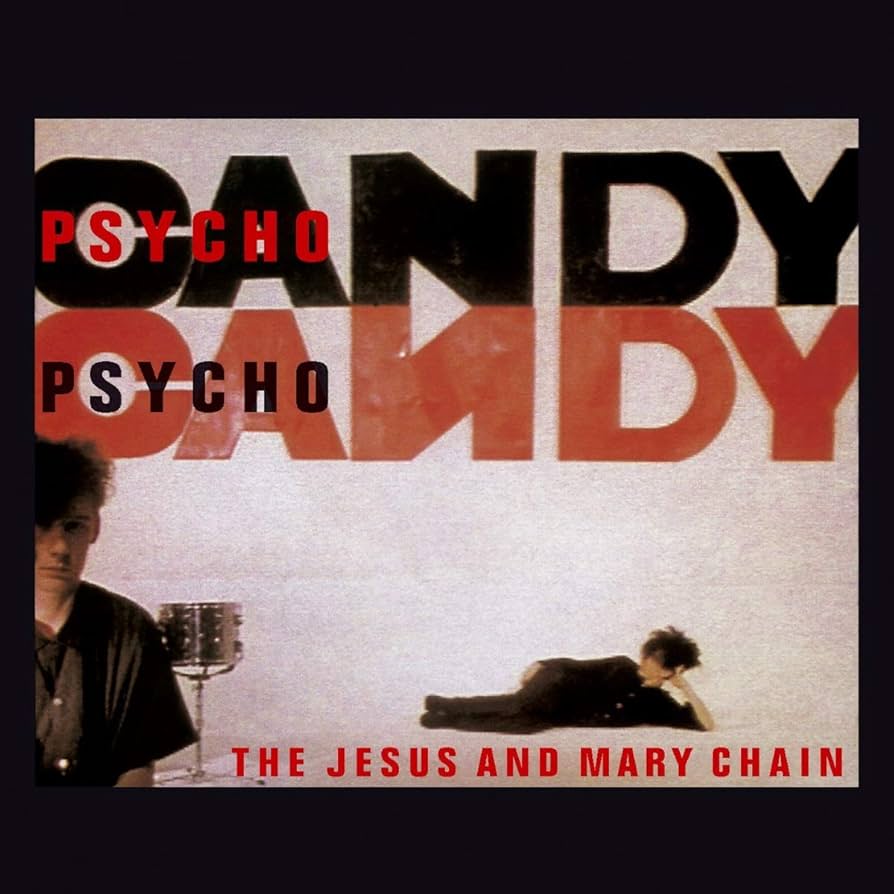

Also: Psychocandy? That is a goddamn great, great name. As chewy and trippy as it seems.

15 years after his interview with Musician, at a festival date in Bruges, David Bowie was practicing vocal scales backstage when a loud voice told him to shut up. The voice’s owner, who emerged from a fitful rest to complain further, proved to be that of a startled, drunk and speed-crazed Jim Reid, at a lower point following the late 90s breakup of the band, there to do a vocal turn with Primal Scream. Per Reid, freely admitting his own embarrassment many years later, Bowie looked him up and down and said “Well… it’s a look,” and walked away.

Then again, not too long after that original interview, Bowie must have first heard the Pixies because for years and years after that he flew their flag high. Interview mentions, showcases during hosting stints and live performances (both of that during Tin Machine stints), an invite to Black Francis to perform at his 50th birthday concert, covering ‘Cactus’ on Heathen the same year he had the run-in with Jim Reid. In the early 90s, he was vocal about his puzzlement that Nirvana had broken out big instead of them, though maybe after that band did their MTV Unplugged special he thought more kindly of the Seattle group.

As far as I can tell, at no point did anyone ask or did Bowie offer an opinion on the fact that in 1991 the Pixies covered a Jesus and Mary Chain song for Trompe Le Monde. Perhaps other things were on his mind.