Wild Dreams. Cool Ambition. Hard Cash. While these words may sound like something you’d associate with a high-octane blockbuster action flick, in reality they are the tagline to a 1995 documentary about life in Sheffield: Tales From A Hard City.

Directed by Kim Flitcroft and filmed in 1993, it captures people navigating life in Sheffield as the city comes out of an era defined by struggle. In the new decade, steelworks have been knocked down and replaced by shopping centres, new sports stadiums and facilities have been built, and the city is trying to shake off its 1980s image of unemployment, industrial decline and political turmoil to become a new destination for retail, leisure, sports and culture. The film follows four people who embody this transitional phase from despair and decline to aspiration and material gain.

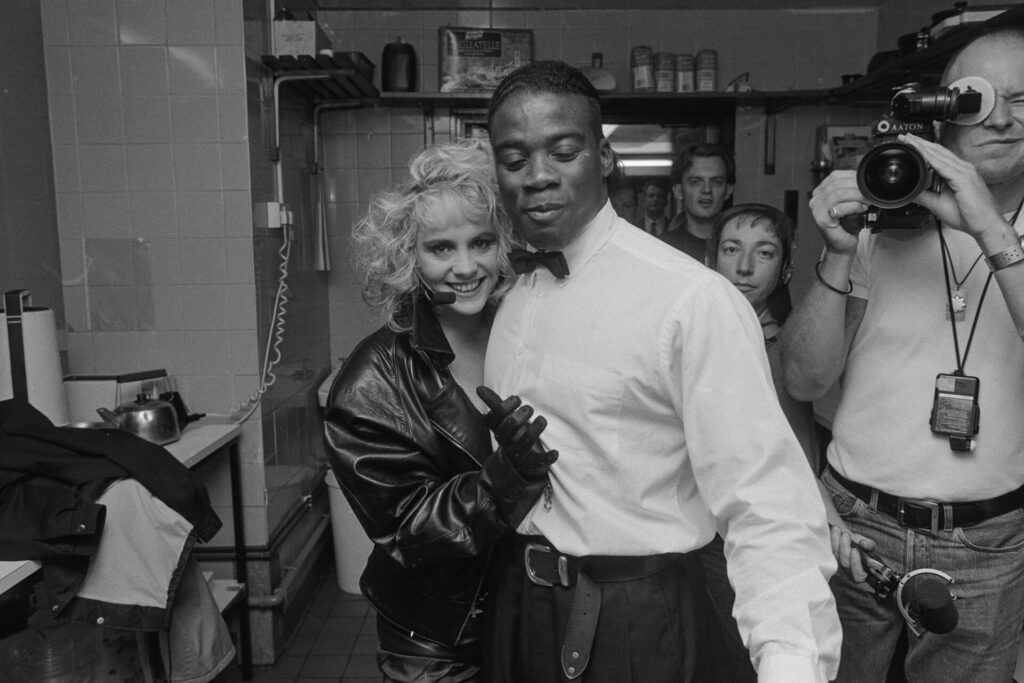

Glen is a petty thief and stoner who wants to make it as a singer. Paul is an ex-professional boxer (who came up via the legendary Brendan Ingle) and is now trying to make it as an actor and model; one who may have his own image consultant but also a stack of ever-growing bills he can’t pay. Wayne is a sleazy, enthusiastic-but-opportunistic businessman, nightclub owner and wannabe media mogul. Sarah is a tabloid sensation who was recently arrested and imprisoned for three days for provocative dancing in a bar in Greece. Wayne decides to try and rebrand the single mum as a saucy singer. He assembles a team to write her a sultry disco-pop song called ‘Dirty Dance’ and they attempt to launch her career in the clubs of Sheffield.

Once hailed as “the greatest Mike Leigh comedy that Leigh never made” by The Independent On Sunday, the film is a very raw, real, and unfiltered look into people’s lives on this journey towards a stardom of sorts. Filmed in the years before the reality TV boom and social media, there is an unguarded candidness and endearing naivety to the people it documents, for whom a camera still carries an element of mystique, wonder, romance and allurement – rather than tired ubiquity.

So much so, you’d almost think it was a mockumentary in parts. Paul speaks excitedly about his ideal acting role as a “trendy cop” who would wear see through t-shirts to reveal his killer body but who is also a “menace”, twisting the heads of suspects inside out with his deft-yet-probing psychological evaluation skills. Glen brags about a range of low-level crimes on camera, as well as opening up about a difficult homelife with a father who struggles with alcohol and his temper. Wayne relishes being in front of the camera with a fat cigar stuck between his teeth at all times, as he comes up with ludicrous ideas on how to make Sarah a sexed-up star. Even his own very young children mock his gaudy approach in doing so. While Sarah herself for the most part seems deeply lost, bewildered and uncomfortable with what’s going on, she still keeps a proud scrapbook of all her press while also pining for a more settled and traditional life.

As the film turns 30 it is to receive an exhibition documenting its making and legacy, along with screenings, in Sheffield as part of No Bounds festival. Curated by the film’s producer, Alex Usborne, in collaboration with Sheffield archive project and record label Memory Dance, it will also feature Flitcroft and Usborne’s earlier Sheffield film about the boxing community, Johnny Fantastic.

While Tales remains a genuinely singular film, with delightfully one-off characters, the documentary is also a fascinating document – existing as both a companion and contrast piece – to another landmark piece of Sheffield culture that turns 30 this month: Pulp’s Different Class.

There’s a strong argument to be made that Different Class is more of a London album than it is a Sheffield one. Jarvis Cocker had been out of the North for years by this point and the capital’s Central Saint Martins, Ladbroke Grove and Soho bars feature in songs more than Sheffield locations. But if you want to fully get a sense of the world that Pulp came out of, and one that led to this album, then Tales is a useful example of scene-setting and context for the record.

The opening track to the album, ‘Mis-Shapes’, is a glorious, rousing ode to freaks, weirdos, misfits and oddballs: the kind of people who faced imminent danger walking the streets of Sheffield in the 1980s and early 90s. The song was written in response to Cocker’s experience of going out in the city. “It was quite dangerous to go into the centre of town on a weekend night,” he later recalled. “You’d get these packs of blokes, all dressed the same in the white short-sleeved shirt, black trousers and loafers, and they’d call you a queer or want to smack you ‘cos they didn’t like your jacket.” Step inside the Fountain Bar, a neon-lit and tinsel-strewn basement bar in Sheffield that features in the film, and you get a sense of the mood that was in the air at this time. There’s one scene in it, as Sarah performs ‘Dirty Dance’, that captures this pack-like mentality, as the crowd is filled with leering, braying, boorish blokes. It’s the kind of aggro-charged atmosphere that feels like it could tip the wrong way if a single foot was put out of place.

Similarly, there’s another moment as Glen and his boys strut confidently through town, numerous bottles of Holsten Pils deep, and into a city centre underpass known locally as “the hole in the road”. Since filled in, in the right light this was once a futuristic modernist concrete landmark that recalled something out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Beaming light from the city above poured into its open-air design and the network of shops and walkways that populated it below ground level. It’s a place that is indelibly marked in the memories of many; a symbol of misty-eyed nostalgia for those who remember going to it as a child and would gaze at the fish tanks that were installed in it. However, for the mis-shapes of the city, it is often remembered more as being a piss-stinking, fear-drenched walkway that was a haven for skinheads and beer monsters to violently attack people. “You couldn’t go through town directly or you’d definitely get beaten up or get a lot of abuse,” Cocker told The Quietus earlier this year. “We had to work out a route through back streets, in order to be safe.”

While Tales is in many ways a contrasting piece to Different Class, as well as a real-time snapshot of the world Pulp came from to help contextualise parts of it, there’s also some connective tissue to be found. There’s absolutely nothing hip, cool, or sexy about the people in Tales who are trying very hard to be hip, cool and sexy – be it Glen singing ‘Wild Thing’ at karaoke with a shirt unbuttoned to the waist or Wayne hiring strippers as extras for Sarah’s single launch. However, Cocker’s ability as a lyricist to peep behind the curtains of Sheffield’s suburban sleaze and to explore sex and iffyness in off-kilter and unromantic settings, means that while tonally worlds apart there are some commonalities simmering away here. Both have roots in the strange underbelly of mundane life in post-industrial Sheffield, and both are working class stories, but despite this proximity and overlap, they are also operating in parallel universes.

While the talent, innovation and years-long artistic slog of Pulp may not be apparent in Tales, which is more based on Wayne’s desire to try and make a quick buck from wannabe artists, it’s still a film that possesses a genuine sense of hope, ambition and desire. Different Class is an album that could have only been made by growing up in Sheffield but it is also an album that could have only been made by leaving it too. As a record, and a band living up to its full potential, it represents a sense of escape, liberation and freedom – a world that has been opened up beyond South Yorkshire. Tales is a film about being stuck in the same kind of confines that Cocker himself had sought to break free from.

In many ways, the people who inhabit Tales are doing the best they can with what they’ve got. There is real chutzpah and swagger to Paul walking into car showroom after car showroom asking for a free car so that he can be a celebrity sponsor for their brand, despite struggling to get work beyond being an extra. “I’m going to be a star,” he tells them. Only when he manages to get genuine interest from Skoda does he clock on that he may actually need to learn to drive.

Similarly, Glen is a trapped dreamer. He sits at home watching karaoke videos of himself and imagines another world – being a singer on stage. “I’ve really got to get my life together,” he says at one point, walking over fields with Sheffield’s vast green and hilly landscape behind him. “I can’t be bumming about smoking draw.” He also seems locked into a world of theft that is so piecemeal that it’s never going to elevate him out of his situation either. One office break-in only results in a £30 loot, and when another opportune moment arises to steal boxes left outside of a warehouse, he’s left with 600 packs of bin liners (which, to his credit, he manages to flog). When a letter from the magistrates’ court arrives telling him he is now going to have to go to prison unless he can pay his mounting fines and debts, he goes on the run, writes a rap about it, and sets about stealing more to try and clear those debts. He’s trapped in a cycle that he can’t break out of.

When Glen is given a shot as a singer – by Wayne, who is impressed by his karaoke – and put in a studio and taken out for fancy meals, and talks of a duo with Sarah emerges, he is perpetually nervous, unsure and awkward. It’s almost as though the very idea of his dreams ever becoming a reality were so far from being a remote possibility that he simply doesn’t know how to interact with it. It’s a moving and poignant depiction that hits home that despite how much people may dream of a way out, a sense of it never happening is often always more firmly entrenched and paralysing.

When the credits roll, we see Glen with headphones on in the studio, producing a primitive albeit fairly groovy bit of trip-hop meets downtempo reggae. It’s a little moment of triumph and success for someone who you can’t help but root for throughout. This remains an even more touching moment given that Glen’s life did not continue with forward momentum. A heavy drug use and drinker, he died in the 2010s as a result of health issues linked to alcoholism. Wayne on the other hand, would later find great success in the catering and hospitality world, inventing the YorkyPud™ Wrap (a roast dinner wrapped up in a Yorkshire pudding, burrito style). Not much is known by the filmmakers about what Sarah and Paul got up to in the years afterwards.

It’s telling that this is a film adored by so many musicians. While it’s funny as hell, and loaded with some amazing one-liners, and there’s farce and tragicomedy, there’s obviously feelings of empathy and relatability that musicians can cling onto. Its depiction of fantasising of another world on a stage, or feeling like you’re stuck and you need desperately to get out, is literally the same situation that Cocker himself was in in Sheffield for years. Fans of the film also range from The Chemical Brothers to Andy Votel, while Badly Drawn Boy’s Damon Gough loves it so much that he once hired out an entire cinema in Manchester to screen it. He invited Glen and his mum – who is quietly the most talented singer in the entire film – and they received a standing ovation. Mogwai programmed it as part of their All Tomorrow’s Parties festival, and Adrian Flanagan of The Moonlandingz and Eccentronic Research Council is DJing the opening party for the exhibition, as it’s his favourite documentary.

So, while Different Class is by far the bigger and more significant anniversary when it comes to the cultural output of Sheffield this month, Tales From A Hard Place is a vital document that provides a peek into a world that led to such a landmark album being forged in the first place. A story of wild dreams, cool ambition and hard cash.

No Bounds Festival runs 10-12 October and the More Tales from A Hard City exhibition runs 10-25 October at Post Hall Gallery, Sheffield. You can watch the original film online here.